Abstract

Understanding the co-occurrence of ecologically similar species remains a puzzling issue in community ecology. The species-rich mouse lemurs (Microcebus spec.) are distributed over nearly all remaining forest areas of Madagascar with a high variability in species distribution patterns. Locally, many congeneric species pairs seem to co-occur, but only little detailed information on spatial patterns is available. Here, we present the results of an intensive capture–mark–recapture study of sympatric Microcebus berthae and M. murinus populations that revealed small-scale mutual spatial exclusion. Nearest neighbour analysis indicated a spatial aggregation in Microcebus murinus but not in M. berthae. Although the diet of both species differed in proportions of food categories, they used the same food sources and had high feeding niche overlap. Also, forest structure related to the spatial distribution of main food sources did not explain spatial segregation because parts used by each species exclusively did not differ in density of trees, dead wood and lianas. We propose that life history trade-offs that result in species aggregation and a relative increase in the strength of intra-specific over inter-specific competition best explain the observed pattern of co-occurrence of ecologically similar congeneric Microcebus species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Knowledge of species spatial distribution patterns and the processes generating these patterns is of fundamental importance to an understanding of population and community ecology (e.g. Diamond 1975; Pianka 1994; Bell 2000; Chesson 2000a; Amarasekare et al. 2004; Kneitel and Chase 2004). Because spatial patterns provide important insights into the coexistence mechanisms of interacting species that form ecological communities, they are a crucial starting point for understanding biogeographical patterns (e.g. MacArthur 1972; Diamond 1975), species diversity (e.g. Ricklefs and Schluter 1993; Rosenzweig 1995; Huston 1999; Amarasekare 2000; Bell 2001; Mouquet and Loreau 2002) as well as the structure and stability of communities (e.g. Elton 1946; Tilman and Karieva 1997). Classical niche theory (recently reviewed by Chase and Leibold 2003) predicts that coexistence is only possible if intra-specific competition is stronger than inter-specific competition, which requires species to be different in their partitioning of resources (Hutchinson 1957; MacArthur and Levins 1967; Tilman 1982), their temporal or spatial partitioning of one resource (e.g. Chesson 2000a, b) or their density- or frequency-dependent predation (e.g. Holt 1977, 1984; Holt et al. 1994).

Hubbell (2001) recently proposed a “unified neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography” that challenged the classic niche-based view of community ecology. This neutral theory is based on the assumption that all species are functionally equivalent in terms of their ecological traits; thus, species assemblages are controlled predominantly by the neutral drift of species abundances (Bell 2001; Hubbell 2001). Hubbell’s approach has generated much controversy (see the recent reviews by Chave 2004; Alonso et al. 2006; Leibold and McPeek 2006; McGill et al. 2006). Whereas the neutral theory was particularly successful in explaining the diversity and distribution of species abundance of tropical trees (e.g. Hubbell et al. 1999; Bell 2000, 2001; Hubbell 2001), the results of many other studies, particularly those focusing on mobile animals, were not consistent with predictions of the neutral model (e.g. McGill 2003; Graves and Rahbek 2005; McGill et al. 2006).

The co-occurrence of congeneric species is still a largely unresolved issue in this context (e.g. Tokeshi 1999; Chesson 2000a; Chase and Leibold 2003; Sfenthourakis et al. 2005) because it seems to contradict predictions of classical niche theory and might therefore also be of significance for discussions of classical niche versus neutral theory (Leibold and McPeek 2006). The aim of this study was to document small-scale spatial patterns of sympatric populations of congeneric Malagasy mouse lemurs (Microcebus murinus and M. berthae, Cheirogaleidae: Primates) and to explore possible mechanisms of their coexistence. Because of their recent common ancestry, closely related species ought to exhibit high similarities in their use of biotic and abiotic resources, susceptibility to predators and responses to disturbances and stress. Due to these similarities, congenerics should compete more intensely and should exhibit higher levels of mutual exclusion than pairs of species from different genera (e.g. MacArthur 1972; Tilman 1982; Holt et al. 1994). Thus, only a few pairs of congeneric species would be expected to exist within a community at any given time (Elton 1946; Pianka 1994). Moreover, current patterns of co-occurrence should provide insight into causal mechanisms that have led to higher order structures, such as competition and niche segregation (e.g. Tokeshi 1999; Bell 2000; Chase and Leibold 2003; Sfenthourakis et al. 2005).

Amarasekare (2003) recently proposed a framework that allows comparative predictions for alternative classes of mechanisms that can explain the coexistence of ecologically similar species, i.e. species that lack differences in (1) partitioning of resources, (2) frequency-dependent predation or (3) temporal partitioning of one resource (e.g. Tilman 1982; Chesson 2000a, b; Chase and Leibold 2003). These coexistence mechanisms focus on spatial niche differences, which depend on the nature of the competitive environment experienced by the interacting species (see also Amarasekare et al. 2004). The competitive environment of any species consists of biotic and abiotic factors that influence its ability to exploit space or limiting resources that vary in space. In a spatially homogeneous competitive environment, defined as no change in the competitive rankings of species found within the spatial area considered, coexistence is most likely to occur via inter-specific trade-offs between life-history attributes that influence competition (e.g. fecundity, longevity) and those that allow species to escape or minimize competition (e.g. dispersal) (Amarasekare 2003). If species do coexist in a homogenous competitive environment, intra-specific clustering and inter-specific segregation at a local scale as well as no covariance between environment and competition are expected. Alternatively, in spatially heterogeneous environments, the competitive rankings of species vary with landscape variation, which leads to greater intra-specific competition than inter-specific competition in favourable areas and greater inter-specific competition than intra-specific competition in unfavourable areas (Chesson 2000a, b). As a result, species are restricted to favourable parts of the habitat and competitively excluded from unfavourable areas. In such situations, source-sink dynamics can lead to stable local coexistence (e.g. Pacala and Roughgarden 1982; Mouquet and Loreau 2002, 2003; Amarasekare et al. 2004).

The species-rich genus Microcebus is distributed over nearly all remaining forest areas of Madagascar, with a high variability in species’ distribution patterns. Mouse lemurs (Microcebus spp.) are small (30–100 g), nocturnal, arboreal primates that form a monophyletic group within the endemic primates of Madagascar (Yoder et al. 2000; Kappeler and Rasoloarison 2003). Whereas in some areas probably only one species exists, several species pairs are found in sympatry in western Madagascar. These pairs generally include the grey mouse lemur (M. murinus), which is widely distributed in the dry deciduous forest along the entire west coast of Madagascar, and another congeneric species with locally restricted ranges [e.g. northwestern Madagascar: M. ravelobensis; western Madagascar: M. berthae (Kirindy, Menabe), M. myoxinus (Bemaraha); south and southwestern Madagascar: M. griseorufus] (Schmid and Kappeler 1994; Zimmermann et al. 1998; Rasoloarison et al. 2000). Several new species of mouse lemurs have recently been described (Kappeler et al. 2005; Louis et al. 2006; Oliveri et al. 2007) so that even more potentially co-existing congeneric species pairs exist in a variety of different habitat types, ranging from evergreen rain forest to dry spiny forest. Although niche separation to other co-existing primates has been shown in some Malagasy forests (Ganzhorn 1988, 1989), only preliminary information exists on the spatial distribution patterns of Microcebus species pairs (see, for example, Rendigs et al. 2003; Schwab and Ganzhorn 2004), an understanding of which is an important prerequisite for illuminating the mechanisms of coexistence (Snyder and Chesson 2003).

By documenting small-scale spatial patterns of sympatric populations of one such species pair (M. murinus and M. berthae), our aim was to explore possible mechanisms of their coexistence. In particular, we addressed the following questions: (1) Are there indications for a stable coexistence or mutual spatial exclusion? (2) Are there indications for intra-specific clustering? (3) Do habitat characteristics, such as forest structure and/or feeding niche partitioning, explain species distribution on a small spatial scale? (4) Which general coexistence mechanism best explains the observed spatial pattern?

Methods

Species

Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur (Microcebus berthae) is the world’s smallest living primate, with an average body weight of about 33 g. After its discovery in 1992 in the dry deciduous forest of western Madagascar (Schmid and Kappeler 1994), it was initially thought to represent a rediscovery of M. myoxinus (Peters 1858), but comparative morphometric and genetic studies revealed its status as a new species, M. berthae (Rasoloarison et al. 2000; Yoder et al. 2000). This species’ currently known distribution (approximately 50 × 30 km) is restricted to the Forêt de Kirindy/CFPF, the nearby Réserve Spécial d’Andranomena and Ambadira forest in central western Madagascar. It appears to have the most restricted range of all known Microcebus spp. (Rasoloarison et al. 2000; Schwab and Ganzhorn 2004). Within its range, Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur is sympatric with the much more widely distributed and larger (60 g) grey mouse lemur (M. murinus). Preliminary observations indicated that the two species are ecologically very similar (Dammhahn and Kappeler 2005). Both are nocturnal solitary foragers that use the fine branch niche and feed mainly on fruit, gum, arthropods and insect secretions (Martin 1972, 1973; Petter 1978; Hladik et al. 1980; Corbin and Schmid 1995). However, details of the feeding ecology of M. berthae are as yet unknown, and these have been only qualitatively described for M. murinus.

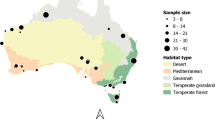

Study site

The study was conducted in the Forêt de Kirindy/CFPF, a dry deciduous forest in western Madagascar, approximately 60 km northeast of Morondava (44°39′E, 20°03′S, 30–60 m a.s.l.). The study site is located within a 12,500-ha forest concession of the Centre de Formation Professionelle Forestière (CFPF) de Morondava. The climate in this area is characterized by pronounced seasonality, with a hot rainy season between December and March and little or no rainfall from April to November (Sorg and Rohner 1996). The forest is very dense, with a comparatively low canopy (for additional information, see Sorg et al. 2003). The study area within the concession (locally known as N5) was defined by the boundaries of a grid system of small foot trails. A rectangular system of small trails was established at 25-m intervals within a 500 × 500-m core area, and each trail intersection was marked for orientation and their coordinates used to create a map. Within the Forêt de Kirindy, both Microcebus species stably co-occur in three different study areas covering more than 150 ha, where populations have been monitored since 1994 using a standard capture–mark–recapture method. Data from line–transect trapping covering an area of several square kilometres in size further supports the generality of this co-occurrence pattern ®. Rasoloarison, L. Schäffler, D. Zinner, unpublished data). Thus, the area chosen for our study is representative. Since it covers a large zone of adjacent populations of both species, it provides access to sufficiently large populations. The population densities in our study area are as high as those at the other study sites and have been relatively constant since 1994.

Capture and marking

We baited a total of 200 Sherman live traps per night with pieces of banana and set them near trail intersections at a height of 0.5–2 m above the ground for three consecutive nights in one-half of the study area (12.5 ha) followed by three consecutive nights in the other half of the study area (12.5 ha). In total, a 25-ha area with 400 trap locations at 25-m intervals was covered. Trapping locations and design were consistent across all trappings, which were performed about once every month: on five occasions in 2002 (August to November), six in 2004 (June, August to December), eight in 2005 (March to July, September to November) and six in 2006 (March, July to November). Traps were opened and baited at dusk and checked and closed at dawn. Captured animals were collected in the early morning and kept at a nearby research station during the day. All newly captured animals were briefly restrained and immobilized with 10 μl Ketanest 100 (Rensing 1999), marked individually with subdermally implanted microtransponders (Trovan, Usling, Germany), sexed and aged (juvenile/adults); a set of standard morphometric measurements were also taken. Recaptured animals were only identified. All animals were released at the site of capture shortly before dusk on the same day.

Spatial patterns

Using all individual trapping points (range of individual trapping points per year: M. murinus 1–24; M. berthae 1–32), we calculated individual mean trapping points per year as the arithmetic means of the x- and y-coordinates of the trapping points and mapped them with ArcView ver. 3.3 (ESRI, Redlands, CA). For each study year, we calculated distances to intra- and inter-specific nearest neighbours for each individual. We subsequently tested for species differences using independent t tests; the nearest-neighbour method was used to test for spatial randomness of species distribution within the study area (Krebs 1998). Based on Clark and Evans (1954), we compared the mean distance to the nearest neighbour [calculated as D = (ΣdI)/n, with n = number of individuals and d I = distance to nearest neighbour of individual I] with the expected distance to the nearest neighbour [calculated as E = 1/(2√p), with p = density of individuals (p = n/A, with A = size of study area)]. We then calculated an index of aggregation as R = D/E, with R = 1 indicating a random pattern, R approaching 0 indicating a clumped pattern and R approaching 2.15 indicating a uniform pattern. We tested for significant deviation from randomness by calculating a z test with z = (D − E)/s and s = 0.2613/(√np) (Krebs 1998).

Co-occurrence

Analysis of co-occurrence between species was based on Diamond’s (1975) hypothesis on checkerboard distributions. Two or more ecologically similar species inhabit exclusive but inter-digitating habitats. Using the co-occurrence module of EcoSim ver. 7.0 (Gotelli and Entsminger 2006), we tested for non-random patterns of species co-occurrence in a presence–absence matrix. C-scores were calculated as the numbers of checkerboard units (CU) as: CU = (r I − S)(r j − S), where S is the number of shared sites (trap locations), and r I and r j are the row totals for species I and species j, respectively (Stone and Roberts 1990). Based on 5000 iterations with proportional representations of species and trap stations, we calculated the expected C-scores (null models) and subsequently tested whether the occurrence of M. berthae and M. murinus at the trap stations deviated from randomness. C-scores larger than expected by chance indicate mutual exclusion between species (Gotelli and Entsminger 2006). We kept species representations (rows) “proportional”, meaning that the probability of trapping an individual of a species was proportional to the observed number of trappings of that species; this condition best reflects differences between species in terms of trapping, such as those due to differences in population size. We did not use the “fixed row” constraint, which was shown to have the lowest probabilities of Type I errors (Gotelli 2000) and was therefore recommended by Gotelli and Entsminger 2006), because keeping the numbers of trappings per species constant is rather unrealistic. We also kept trap location representations (columns) “proportional”, meaning that the probability of trapping an individual of either species at a particular trap site was proportional to the observed number of trappings at that site. This column constraint best reflects spatial heterogeneity in trapping probability as compared to an equiprobable representation while also allowing more variation in the simulations than a fixed columns constraint.

Feeding ecology

Data on diet was obtained by means of direct focal observation (Altmann 1974) between June and December 2004–2006, a period that coincides with the dry and the beginning of the wet season in the Forêt de Kirindy and is thus the time when food is most limiting (M. Dammhahn and P.M. Kappeler, unpublished data). We equipped a total of 13 M. berthae and 16 M. murinus females with radio collars (M. murinus: 2 g; TW4, Biotrack, UK; M. berthae: 1, 8 g; BD-2, Holohil, Canada). Focal animals were followed during their nocturnal activity for 1–4 h before switching to another M. berthae or M. murinus individual. The observation time was chosen opportunistically but was spread evenly between 1800 hours and 0100 hours for every animal (prior analyses showed that there is no difference in feeding behaviour between the first and second half of the night). We collected behavioural data cumulatively for observation intervals of 1 min (one–zero sampling) (Martin and Bateson 1993) and recorded all occurrences of feeding behaviour. Food items were categorized into arthropods, fruit, flowers, gum, homopteran secretions, vertebrates and unknown. In total, we observed Madame Berthe’s mouse lemurs for 213 h and grey mouse lemurs for 171 h. Due to low visibility in a dense forest at night, animals were in sight only in 48% of the 1-min observation intervals for M. berthae and 71% for M. murinus. The difference between these species in terms of visibility was due to overall higher mobility of M. berthae. All analyses are based on 1-min observation intervals when the animal was in sight. Differences in the diets of the two Microcebus species were analysed using absolute frequencies and the chi-square test.

Feeding niche overlap was calculated using Pianka’s index (Pianka 1973; Krebs 1998) based on food categories. This symmetrical index O jk ranges from 0 (no resources in common) to 1 (complete overlap) and is calculated as:

with p ij = proportion resource category i of the total resources used by species j, and p ik = proportion resource category i of the total resources used by species k. We determined the statistical significance of the observed niche overlap by comparing it with an appropriate null model calculated by the niche overlap function in EcoSim ver. 7.72 software (Gotelli and Entsminger 2006) in which the observed resource utilization data were randomized among species in 1000 simulations. We used the RA4 algorithm to calculate expected niche overlap indices. This algorithm retained both the observed niche breadth of each species and the pattern of zero resource states by reshuffling only the non-zero entries for each resource. RA4 is the most conservative algorithm and thus has the greatest chance of revealing significant patterns of reduced niche overlap (Winemiller and Pianka 1990; Gotelli and Entsminger 2006). Mean simulated niche overlap was then compared to observed overlap. Resource niche partitioning should cause mean niche overlap to be less than expected by chance.

Vegetation plots

To estimate forest structure related to the main food sources of mouse lemurs, we measured several microhabitat variables. We estimated the density of trees, which is highly related to the density of fruit and gum sources, and the density of lianas, which determines the density of homopteran secretions because the insects (Flatida coccinea, Homoptera, Fulgoridae) producing these sugary secretions aggregate and feed exclusively on lianas (Hladik et al. 1980). Additionally, the density of living and dead trees provided an estimate of the availability of tree holes, another important resource (sleeping sites) for mouse lemurs. For the last two study years (2005 and 2006), the species trap locations were weighted by trapping frequency with every individual counting once per location. The eight (in 2005) and ten (in 2006) most frequented locations per year were chosen for each species. Subsequently, quadrates of 10 × 10 m were designed, with the trap location representing one corner of the quadrates. We counted the total number of trees >5 cm diameter at breast height (DBH), number of standing dead wood (DBH >5 cm and length >1 m) and number of liana stocks within every quadrate. Mann–Whitney U tests were calculated to examine differences between quadrates at M. murinus and M. berthae trapping locations. Significance for all tests was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Capture and spatial pattern

In 30,000 trap nights over 4 years we caught a total of 142 M. berthae individuals, between 24 and 55 per year, and 162 M. murinus individuals, between 49 and 71 per year (Table 1). Trapping data revealed constant small-scale spatial separation between the two species (Fig. 1). In all four study years, the mean distances to the nearest conspecific neighbour were smaller in M. murinus than in M. berthae (t tests, 2002: t = 4.50, df = 92, P < 0.0001; 2004: t = −4.64, df = 78, P < 0.0001; 2005: t = −3.45, df = 123, P < 0.001; 2006: t = −4.79, df = 94, P < 0.0001). Moreover, M. murinus individuals were significantly clumped in the study area, whereas the distribution of M. berthae did not differ from complete spatial randomness (Table 2). Also, mean distances to the nearest inter-specific neighbour (mean values ± SD 2002: 136 ± 81; 2004: 126 ± 100; 2005: 94 ± 66; 2006: 103 ± 80) were larger than those to the nearest intra-specific neighbour (Table 2) (t tests, 2002: t = 4.50, df = 92, P < 0.0001; 2004: t = −4.64, df = 78, P < 0.0001; 2005: t = −3.45, df = 123, P < 0.001; 2006: t = −4.79, df = 94, P < 0.00001), indicating spatial segregation between the species.

Co-occurrence

Of the 400 possible trapping sites, the two species shared only a small number in each study year (ten in 2002, two in 2004, 17 in 2005, 24 in 2006), and most trapping sites were exclusively occupied by one species (Table 3). For every study year, observed C-scores were higher than expected based on 5000 simulations, indicating inter-specific spatial segregation (Table 4).

Feeding ecology

Both Microcebus species had an omnivorous diet and used the same food sources, including sugary homopteran secretions, fruit, flowers, gum, arthropods and small vertebrates (e.g. geckos, chameleons). However, the feeding patterns of the two species differed in the proportions of these food categories (chi-square test, χ 2 = 265.9, df = 4, P < 0.001) (Table 5). Microcebus berthae mainly fed on a sugary secretion produced by homopteran larvae, which amounted to as much as 82% of their overall diet; the diet was further supplemented by animal matter. The diet of M. murinus was more diverse, including generally higher amounts of fruit and gum. Both species consumed similar amounts of animal matter. Feeding niche overlap was high, and observed overlap was higher than the expected overlap [O jk(obs) = 0.97, O jk(exp) = 0.39, P < 0.05).

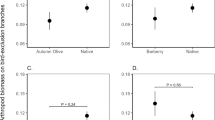

Vegetation plots

All weighted trapping points were exclusive by species. Vegetation plots at M. berthae and M. murinus trapping points did not differ in mean density of trees >5 cm DBH (MWU test, z = 1.2, P = 0.1249), mean number of standing dead wood (MWU test, z = −0.57, P = 0.5653) and mean number of lianas (MWU test, z = 0.51, P = 0.6093) (Fig. 2).

Habitat characteristics. Vegetation plots at M. berthae (n = 18) and M. murinus (n = 18) most frequented trapping points did not differ in terms of tree density (a), number of standing dead wood (b) and number of lianas (c) (MWU tests). Shown are the medians, inter-quartile ranges (box) and minimum–maximum ranges (whiskers)

Discussion

The results of intensive trapping over a 4-year period indicated mutual spatial exclusion between M. berthae and M. murinus on a small spatial scale. Within the study area, M. murinus individuals were spatially clumped, whereas M. berthae individuals were randomly spaced. Although the diet of both species differed in the proportions of food categories, both used the same food source categories and had high feeding niche overlap. Thus, feeding niche partitioning most likely is not the underlying mechanism that led to the observed spatial pattern. Further, forest structure related to the spatial distribution of main food sources did not explain spatial segregation because habitat parts used by each species exclusively did not differ in terms of the mean density of trees, dead wood and lianas. Instead, we propose that life-history trade-offs that result in species aggregation and a relative increase in the strength of intra-specific over inter-specific competition best explain the observed co-occurrence pattern of these ecologically similar Microcebus species.

Although Madame Berthe’s and grey mouse lemurs have been shown to co-occur regionally and have stably co-existed locally in our study area for more than 15 years (Schmid and Kappeler 1994; Rasoloarison et al. 2000; Schwab and Ganzhorn 2004), they mutually exclude each other on the smallest spatial scale (see also Schwab and Ganzhorn 2004). Both the results of co-occurrence patterns based on Diamond’s (1975) hypothesis on checkerboard distributions and the relative large distances to inter- versus intra-specific nearest neighbour indicate spatial segregation between the two Microcebus species. Furthermore, nearest neighbour analysis revealed that on this local scale, M. murinus individuals were spatially clustered, whereas M. berthae individuals were dispersed and randomly spaced.

Feeding niche partitioning can not explain these spatial patterns because (1) both Microcebus species fed on the same food categories and their diet differed only in relative proportions, (2) the feeding niche of M. berthae fell completely within the wider niche of M. murinus, which is also reflected by the high feeding niche overlap and (3) basic characteristics of forest structure that are related to the distribution of main food resources did not correspond to the spatial distribution of the two species. Forest parts used by each species exclusively did not differ in structural characteristics. In contrast, previous studies suggested differences in microhabitat preferences to explain distribution patterns in Microcebus species (Rendigs et al. 2003; Schwab and Ganzhorn 2004). In co-occurring M. murinus and M. ravelobensis, forest structure characteristics corresponded to an uneven distribution pattern, with areas of co-existence and areas of exclusive use by one species (Rendigs et al. 2003). However, relatively high coefficients of association in a small area of sympatry imply low inter-specific spatial segregation on this spatial scale.

For M. murinus and M. berthae, Schwab and Ganzhorn (2004) discussed specific habitat requirements for M. berthae. However, in the same forest part also studied here (locally known as N5), differences in microhabitat structure between used and unused parts were marginal; of six variables measured in their study, Schwab and Ganzhorn (2004) only found a 7% difference in vegetation cover at intermediate level (30–160 cm). Vegetation cover, however, was only estimated by eye to the nearest 10% and these estimates showed high variation within site categories. Microcebus murinus apparently did not prefer any particular microhabitat (Schwab and Ganzhorn 2004; this study). Additionally, analyses of forest composition of the study area (C. Grossheim and J. U. Ganzhorn, unpublished data) provided no evidence for spatial differences in the distribution of fruit and gum tree species used by mouse lemurs. Thus, spatial clumping in M. murinus does not appear to be explained by ecological factors. Overall, the observed spatial pattern of inter-specific segregation and intra-specific clustering within a given forest part is not likely to be explained by feeding niche partitioning and corresponding habitat characteristics, but might be based instead on mechanisms of competitive coexistence.

With a body mass of 60 g, M. murinus individuals are about twofold larger than M. berthae individuals and should, therefore, be superior in terms of direct competition. Whereas feeding competition between the two species has not yet been demonstrated experimentally, behavioural observations of inter-specific interactions at feeding sites suggested feeding priority of M. murinus (M. Dammhahn, unpublished observations). There are two reasons why one can assume that the competitive rankings of the two Microcebus species do not change in space on a small to medium scale (homogeneous competitive environment; Amarasekare 2003). First, the superior species (M. murinus) is the generalist, which inhabits even degraded, low-quality forest (Ganzhorn 1995). Second, a predator-mediated change in competitive rankings is unlikely (e.g. Chesson 2000a; Chase et al. 2002) because none of the known predators (carnivores: Cryptoprocta ferox, Mungotictis decemlineata; snakes: Ithycyphys miniatus, Sanzinia madagascariensis; raptors: Accipiter henstii; owls Tyto alba, Asio madagascariensis) is specialized on one of the species (Goodman et al. 1993; Rasoloarison et al. 1995; M. Dammhahn, unpublished data), and predation pressure is higher for the inferior M. berthae (up to 70% mortality) than for the superior M. murinus (up to 50% mortality) (M. Eberle, unpublished data; M. Dammhahn, unpublished data).

Population density of the superior competitor (M. murinus) is higher than that of the inferior one (M. berthae), and mean distances to same-species nearest neighbours are smaller than those between heterospecifics. Thus, coexistence via heteromyopia, defined as competitive interactions between heterospecific individuals occurring over shorter distances than those among same species individuals (Murrell and Law 2003), is unlikely in Microcebus conspecifics. If we exclude heteromyopia as a mechanism—within a homogeneous competitive environment—coexistence is most likely facilitated by inter-specific trade-offs between life-history attributes that increase a species’ competitive abilities, such as fecundity and longevity, and those that allow species to escape or minimize competition, such as dispersal (Amarasekare 2003). Two coexistence mechanisms are possible: (1) niche succession (e.g. Pacala and Rees 1998; Bolker and Pacala 1999) and (2) competition–colonization trade-off (e.g. Pacala and Roughgarden 1982; Loreau and Mouquet 1999; Mouquet and Loreau 2002; 2003) (Amarasekare 2003; Amarasekare et al. 2004). Niche succession would require that the superior competitor lacks the ability to exploit resource-rich conditions characteristic of recently disturbed (early successional) habitats. In contrast to the prediction of niche succession, M. murinus, and not M. berthae, was shown to inhabit even degraded and secondary forest (Ganzhorn 1994, 1995; Schwab and Ganzhorn 2004).

The general mechanism underlying coexistence via a competition–colonization trade-off is that superior competitors cannot exploit all of the available space because they are limited in their fecundity, recruitment or dispersal and, thus, leave gaps in the landscape that inferior competitors can exploit (Amarasekare 2003; Amarasekare et al. 2004). M. murinus shows patchy distribution in a continuous undisturbed forest with aggregation on the smallest (i.e. several 10 ha (Wimmer et al. 2002; this study) and the next largest (several km2) spatial scale, and gaps in their distribution stretching several home-range diameters within a continuous habitat without geographic barriers (Fredsted et al. 2004, 2005). Ecological constraints are unlikely to explain this spatial heterogeneity because this species seems to be ecologically very tolerant (Radespiel 2006) and has been found in various forest types, including intact primary evergreen littoral, dry deciduous and arid spiny forest (Ganzhorn 1995; Ganzhorn et al. 1997; Ramanamanjato and Ganzhorn 2001; Rendigs et al. 2003; Rasoazanabary 2004; Schwab and Ganzhorn 2004), disturbed and secondary forest (Ganzhorn 1995; Ganzhorn and Schmid 1998) and even plantations (Ganzhorn 1987).

Female philopatry (Wimmer et al. 2002) in combination with cooperative breeding of closely related females (Eberle and Kappeler 2006) might lead to female clusters in space and thus clumped population patches in M. murinus. Females form stable matrilineal groups, and incidences of adoption and allonursing in group-breeding females suggest that the reproductive success of cooperatively breeding females is higher than that of females breeding alone (Eberle and Kappeler 2006). Also, survival benefits are obtained by the presence of close kin (Lutermann et al. 2006). A similar pattern is unlikely in M. berthae because females do not form permanent sleeping groups, and females that were opportunistically associated with each other were not close kin (Dammhahn and Kappeler 2005). Further, preliminary data on genetic population structure has provided no evidence for the existence of spatial clusters of closely related females (matrilines) (Dammhahn and Kappeler 2005). Benefits from limited dispersal for M. murinus females, in combination with limited recruitment due to high predation pressure (up to 50% mortality, M. Eberle, unpublished data, M. Dammhahn, unpublished data), may result in spatial population clusters and an increase in the strength of intra-specific competition relative to inter-specific competition, thus facilitating the coexistence of ecologically similar Microcebus species.

References

Alonso D, Etienne RS, McKane AJ (2006) The merits of neutral theory. Trends Ecol Evol 21:451–457

Altmann J (1974) Observational study of behaviour: sampling methods. Behaviour 49:227–267

Amarasekare P (2000) The geometry of coexistence. Biol J Linn Soc 71:1–31

Amarasekare P (2003) Competitive coexistence in spatially structured environments: a synthesis. Ecol Lett 6:1109–1122

Amarasekare P, Hoopes MF, Mouquet N, Holyoak M (2004) Mechanisms of coexistence in competitive metacommunities. Am Nat 164:310–326

Bell G (2000) The distribution of abundance in neutral communities. Am Nat 155:606–617

Bell G (2001) Neutral macroecology. Science 293:2413–2418

Bolker BM, Pacala SW (1999) Spatial moment equations for plant competition: understanding spatial strategies and the advantages of short dispersal. Am Nat 153:575–602

Chase JM, Leibold MA (2003) Ecological niches. Linking classical and contemporary approaches. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Chase JM, Abrams PA, Grover JP, Diehl S, Chesson P, Holt RD, Richards SA, Nisbet RM, Case TJ (2002) The interaction between predators and competition: a review and synthesis. Ecol Lett 5:302–315

Chave J (2004) Neutral theory and community ecology. Ecol Lett 7:241–253

Chesson P (2000a) General theory of competitive coexistence in spatially-varying environments. Theor Popul Biol 58:211–237

Chesson P (2000b) Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 31:343–366

Clark PJ, Evans FC (1954) Distance to nearest neighbor as a measure of spatial relationships in populations. Ecology 35:445–453

Corbin GD, Schmid J (1995) Insect secretions determine habitat use patterns by a female lesser mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus). Am J Primatol 37:317–324

Dammhahn M, Kappeler PM (2005) Social system of Microcebus berthae, the world’s smallest primate. Int J Primatol 26:407–435

Diamond JM (1975) Assembly of species communities. In: Cody ML, Diamond JM (eds) Ecology and evolution of communities. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp 342–444

Eberle M, Kappeler PM (2006) Family insurance: kin selection and cooperative breeding in a solitary primate (Microcebus murinus). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 60:582–588

Elton C (1946) Competition and the structure of ecological communities. J Anim Ecol 15:54–68

Fredsted T, Pertoldi C, Olesen JM, Eberle M, Kappeler PM (2004) Microgeographic heterogeneity in spatial distribution and mtDNA variability of gray mouse lemurs (Microcebus murinus, Primates: Cheirogaleidae). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 56:393–403

Fredsted T, Pertoldi C, Schierup MH, Kappeler PM (2005) Microsatellite analyses reveal fine-scale genetic structure in grey mouse lemurs (Microcebus murinus). Mol Ecol 14:2363–2372

Ganzhorn JU (1987) A possible role of plantations for primate conservation in Madagascar. Am J Primatol 12:205–215

Ganzhorn JU (1988) Food partitioning among Malagasy primates. Oecologia 75:436–450

Ganzhorn JU (1989) Niche separation of seven lemur species in the eastern rainforest of Madagascar. Oecologia 79:279–286

Ganzhorn JU (1994) Lemurs as indicators for habitat change. In: Thierry B, Anderson JR, Roeder JJ, Herrenschmidt N (eds) Ecology and evolution. Universite Louis Pasteur, Strasbourg, pp 51–56

Ganzhorn JU (1995) Low-level forest disturbance effects on primary production, leaf chemistry, and lemur populations. Ecology 76:2084–2096

Ganzhorn JU, Schmid J (1998) Different population dynamics of Microcebus murinus in primary and secondary deciduous dry forests of Madagascar. Int J Primatol 19:785–796

Ganzhorn JU, Malcomber S, Andrianantoanina O, Goodman SM (1997) Habitat characteristics and lemur species richness in Madagascar. Biotropica 29:331–343

Goodman SM, O’Connor S, Langrand O (1993) A review of predation on lemurs: implications for the evolution of social behaviour in small mammals. In: Kappeler PM, Ganzhorn JU (eds) Lemur social systems and their ecological basis. Plenum Press, New York, pp 51–66

Gotelli NJ (2000) Null model analysis of species co-occurrence patterns. Ecology 81:2606–2621

Gotelli NJ, Entsminger GL (2006) EcoSim: null models software for ecology. Version 7. Acquired Intelligence & Kesey-Bear, Jericho

Graves GR, Rahbek C (2005) Source pool geometry and the assembly of continental avifaunas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:7871–7876

Hladik CM, Charles-Dominique P, Petter JJ (1980) Feeding strategies of five nocturnal prosimians in the dry forest of the west coast of Madagascar. In: Charles-Dominique P, Cooper HM, Hladik A, Hladik CM, Pages E, Pariente GF, Petter-Rousseaux A, Schilling A (eds) Nocturnal Malagasy primates. Academic, New York, pp 41–73

Holt RD (1977) Apparent competition and the structure of prey communities. Theor Popul Biol 12:197–229

Holt RD (1984) Spatial heterogeneity, indirect interactions, and the coexistence of prey species. Am Nat 124:377–406

Holt RD, Grover J, Tilman D (1994) Simple rules for interspecific dominance in systems with exploitative and apparent competition. Am Nat 144:741–771

Hubbell SP (2001) The unified neutral theory of species abundance and diversity. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Hubbell SP, Foster RB, O’Brien ST, Harms KE, Condit R, Wechsler B, Wright SJ, Loo de Lao S (1999) Light-gap disturbances, recruitment limitation, and tree diversity in a Neotropical forest. Science 283:554–557

Huston MA (1999) Local processes and regional patterns: appropriate scales for understanding variation in the diversity of plants and animals. Oikos 86:393–401

Hutchinson GE (1957) Concluding remarks. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 22:415–427

Kappeler PM, Rasoloarison RM (2003) Microcebus, Mouse lemurs, Tsidy. In: Goodman SM, Benstead JP (eds) The natural history of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 1310–1315

Kappeler PM, Rasoloarison RM, Razafimanantsoa L, Walter L, Roos C (2005) Morphology, behaviour and molecular evolution of giant mouse lemurs (Mirza spp.) GRAY, 1870, with describtion of a new species. Primate Rep 71:3–26

Kneitel JM, Chase JM (2004) Trade-offs in community ecology: linking spatial scales and species coexistence. Ecol Lett 7:69–80

Krebs CJ (1998) Ecological methodology. Addison-Welsey Educational Publ, Menlo Park

Leibold MA, McPeek MA (2006) Coexistence of the niche and neutral perspectives in community ecology. Ecology 87:1399–1410

Loreau M, Mouquet N (1999) Immigration and the maintenance of local species diversity. Am Nat 154:427–440

Louis EE Jr, Coles MS, Andriantompohavana R, Sommer JA, Engberg SE, Zaonarivelo JR, Mayor MI, Brenneman RA (2006) Revision of the mouse lemurs (Microcebus) of eastern Madagascar. Int J Primatol 27:347–389

Lutermann H, Schmelting B, Radespiel U, Ehresmann P, Zimmermann E (2006) The role of survival for the evolution of female philopatry in a solitary forager, the grey mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus). Proc R Soc Lond B 273:2527–2533

MacArthur RH (1972) Geographical ecology. Princeton University Press, Princeton

MacArthur RH, Levins R (1967) The limiting similarity, convergence, and divergence of coexisting species. Am Nat 101:377–385

Martin A, Bateson P (1993) Measuring behaviour. An introductory guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Martin RD (1972) A preliminary field-study of the lesser mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus J.F. Miller, 1977). In: Charles-Dominique P, Martin RD (eds) Behaviour and ecology of nocturnal prosimians. Field studies in Gabon and Madagascar. Paul Parey, Berlin, pp 43–85

Martin RD (1973) A review of the behaviour and ecology of the lesser mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus J.F. Miller 1777). In: Michael RP, Crook JH (eds) Comparative ecology and behaviour of primates. Academic, London, pp 1–68

McGill BJ (2003) A test of the unified neutral theory of biodiversity. Nature 422:881–885

McGill BJ, Maurer BA, Weiser MD (2006) Empirical evaluation of neutral theory. Ecology 87:1411–1423

Mouquet N, Loreau M (2002) Coexistence in metacommunities: the regional similarity hypothesis. Am Nat 159:420–426

Mouquet N, Loreau M (2003) Community patterns in source-sink meta-communities. Am Nat 162:544–557

Murrell DJ, Law R (2003) Heteromyopia and the spatial coexistence of similar competitors. Ecol Lett 6:48–59

Oliveri G, Zimmermann E, Randrianambinina B, Rasoloharijaona S, Rakotondravony D, Gutschanski K, Radespiel U (2007) The ever-increasing diversity in mouse lemurs: Three new species in north and northwestern Madagascar. Mol Phylogenet Evol 43:309–327

Pacala SW, Rees M (1998) Models suggesting field experiments to test two hypotheses explaining successional diversity. Am Nat 152:729–737

Pacala SW, Roughgarden J (1982) Spatial heterogeneity and interspecific competition. Theor Popul Biol 21:92–113

Petter JJ (1978) Ecological and physiological adaptations of five sympatric nocturnal lemurs to seasonal variation in food production. In: Chivers DJ, Herbert J (eds) Recent advances in primatology, vol 1. Behaviour. Academic, London, pp 211–223

Pianka ER (1973) The structure of lizard communities. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 4:53–74

Pianka ER (1994) Evolutionary ecology. Harper-Collins College, New York

Radespiel U (2006) Ecological diversity and seasonal adaptations of mouse lemurs (Microcebus spp.). In: Gould L, Sauther ML (eds) Lemur ecology and adaptation. Springer, New York, pp 211–233

Ramanamanjato J-B, Ganzhorn JU (2001) Effects of forest fragmentation, introduced Rattus rattus and the role of exotic tree plantations and secondary vegetation for the conservation of an endemic rodent and a small lemur in littoral forests of southeastern Madagascar. Anim Conserv 4:175–183

Rasoazanabary E (2004) A preliminary study of mouse lemurs in Beza Mahafaly Special Reserve, southwestern Madagascar. Lemur News 9:4–7

Rasoloarison RM, Rasoloandrasana BPN, Ganzhorn JU, Goodman SM (1995) Predation on vertebrates in the Kirindy Forest, western Madagascar. Ecotropica 1:59–65

Rasoloarison RM, Goodman SM, Ganzhorn JU (2000) Taxonomic revision of mouse lemurs (Microcebus) in the western portions of Madagascar. Int J Primatol 21:963–1019

Rendigs A, Radespiel U, Wrogemann D, Zimmermann E (2003) Relationship between microhabitat structure and distribution of mouse lemurs (Microcebus spp.) in northwest Madagascar. Int J Primatol 24:47–64

Rensing S (1999) Immobilization and anesthesia of nonhuman primates. Primate Rep 55:33–38

Ricklefs RE, Schluter D (1993) Species diversity in ecological communities: historical and geographical perspectives. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Rosenzweig ML (1995) Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Schmid J, Kappeler PM (1994) Sympatric mouse lemurs (Microcebus spp.) in western Madagascar. Folia Primatol 63:162–170

Schwab D, Ganzhorn JU (2004) Distribution, population structure and habitat use of Microcebus berthae compared to those of other sympatric Cheirogaleids. Int J Primatol 25:307–330

Sfenthourakis S, Tzanatos E, Giokas S (2005) Species co-occurrence: the case of congeneric species and a causal approach to patterns of species associations. Global Ecol Biogeogr 15:39–49

Snyder RE, Chesson P (2003) Local dispersal can facilitate coexistence in the presence of permanent spatial heterogeneity. Ecol Lett 6:301–309

Sorg JP, Rohner U (1996) Climate and tree phenology of the dry deciduous forest of the Kirindy Forest. In: Ganzhorn JU, Sorg JP (eds) Ecology and economy of a tropical dry forest in Madagascar. Goltze, Göttingen, pp 57–80

Sorg JP, Ganzhorn JU, Kappeler PM (2003) Forestry and research in the Kirindy Forest/Centre de Formation Professionnelle Forestière. In: Goodman SM, Benstead JP (eds) The natural history of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 1512–1519

Stone L, Roberts A (1990) The checkerboard score and species distribution. Oecologia 85:74–79

Tilman D (1982) Resource competition and community structure. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Tilman D, Karieva P (1997) Spatial ecology: the role of space in population dynamics and interspecific interactions. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Tokeshi M (1999) Species coexistence. Ecological and evolutionary perspectives. Blackwell Science, Oxford

Wimmer B, Tautz D, Kappeler PM (2002) The genetic population structure of the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus), a basal primate from Madagascar. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 52:166–175

Winemiller KO, Pianka ER (1990) Organization in natural assemblages of desert lizards and tropical fishes. Ecol Monogr 60:27–55

Yoder AD, Rasoloarison RM, Goodman SM, Irwin JA, Atsalis S, Ravosa MJ, Ganzhorn JU (2000) Remarkable species diversity in Malagasy mouse lemurs (primates, Microcebus). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:11325–11330

Zimmermann E, Cepok S, Rakotoarison N, Zietemann V, Radespiel U (1998) Sympatric mouse lemurs in north-west Madagascar: a new rufous mouse lemur species (Microcebus ravelobensis). Folia Primatol 69:106–114

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the authorization and support of this study by Prof. O. Ramilijaona and Dr. D. Rakotondravony (Département de Biologie Animale, Université d’Antananarivo), the Commission Tripartite and the CAFF of the Direction des Eaux et Forêts, the CFPF Morondava. We thank Rodin Rasoloarison, Léon Razafimanantsoa, Tiana Andrianjanahary, Jean-Claude de Beroboka, Bruno Tsiverimana and the Equipe Kirindy for support and assistance in the field. A previous version of the manuscript benefited greatly from comments from Mia-Lana Lührs, two anonymous reviewers and discussions in the Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology Department of the DPZ. Financial support was generously provided by DFG (Ka 1082/10-1&2), the Margot-Marsh Biodiversity Foundation, Deutsches Primatenzentrum Göttingen and the Christian-Vogel-Fonds (GfP). All research reported in this manuscript is in compliance with animal care regulations and applicable national laws of Germany and Madagascar. All research protocols were approved by the appropriate Animal Use and Care committees of Germany (Bundesministerium für Naturschutz, BfN) and Madagascar (Ministère de l’Environment et des Eaux et Forêts, MINEEF).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Roland Brandl.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dammhahn, M., Kappeler, P.M. Small-scale coexistence of two mouse lemur species (Microcebus berthae and M. murinus) within a homogeneous competitive environment. Oecologia 157, 473–483 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-008-1079-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-008-1079-x