Abstract

We explored the possibility that increasing participants’ motivation to perform well on a focal task can reduce mind wandering. Participants completed a sustained-attention task either with standard instructions (normal motivation), or with instructions informing them that they could be excused from the experiment early if they achieved a certain level of performance (higher motivation). Throughout the task, we assessed rates of mind wandering (both intentional and unintentional types) via thought probes. Results showed that the motivation manipulation led to significant reductions in both intentional and unintentional mind wandering as well as improvements in task performance. Most critically, we found that our simple motivation manipulation led to a dramatic reduction in probe-caught mind-wandering rates (49%) compared to a control condition (67%), which suggests the utility of motivation-based methods to reduce people’s propensity to mind-wander.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the motivation condition, the performance criterion for leaving the experiment early was exceptionally lax (although participants were unaware of this): to meet this criterion, participants merely had to respond (via a spacebar press) to at least one of the 900 MRT tones. As anticipated, all participants met and surpassed this criterion and they were all therefore excused from the experiment after approximately 30 min. On the other hand, all of the participants in the control condition were informed, after approximately 30 min (i.e., after completing 900 MRT trials) that they could leave the experiment early (irrespective of their performance on the MRT; although all of these participants likewise met and surpassed the criterion that we had set for the motivation condition).

In the motivation condition, to avoid possible contamination due to demand characteristics, the responses to the motivation question were obtained after participants learned that they could leave the study early (to maintain consistency across conditions, in the control condition, we also obtained motivation responses after participants learned that they could leave the study early).

For more information surrounding the rationale behind computing the variance measure in this manner, see Seli, Carriere, Levene, & Smilek (2013a).

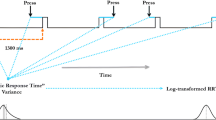

Upon examining the psychometric properties of the primary variables of interest, we found that the distribution of omissions was non-normal (skewness >2, kurtosis >4; Kline, 1998; all other variables had normally distributed data). In an attempt to normalize the omission data, we conducted a log 10 transformation, which was effective (after the transformation, skewness <2, kurtosis <4; Kline, 1998). However, irrespective of whether our succeeding analyses were conducted on the transformed or non-transformed omission data, the same patterns of results emerged. Thus, to retain meaningful mean values for the omission rates, all analyses involving omission data were conducted while using the non-transformed values.

This may be particularly true in the present experiment, given that participants were not provided a clear performance criterion, and given that MRT response variability (one of the primary measures of interest) is not likely to be easily monitored by participants. This suggests the possibility that, if participants were to complete a task whose performance measure(s) were more transparent, and one in which they could better monitor their performance, high motivation may lead to greater reductions in intentional mind wandering compared with the reductions observed here (we thank Dr. Michael Kane for suggesting this possibility).

Critically, the motivation-based account and the executive-failures account (McVay & Kane, 2010) are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Indeed, mind wandering could result from a lack of motivation to attend to a focal task, and/or as a result of poor executive control.

References

Antrobus, J. S., Singer, J. L., & Greenberg, S. (1966). Studies in the stream of consciousness: experimental enhancement and suppression of spontaneous cognitive processes. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 23, 399–417.

Barron, E., Riby, L. M., Greer, J., & Smallwood, J. (2011). Absorbed in thought the effect of mind wandering on the processing of relevant and irrelevant events. Psychological Science, 22, 596–601.

Brown, K. W. (2007). Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 211–237.

Davidson, R. J., & Kaszniak, A. W. (2015). Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. American Psychologist, 70, 581–592.

Eberth, J., & Sedlmeier, P. (2012). The effects of mindfulness meditation: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 3, 174–189.

Giambra, L. M. (1995). A laboratory method for investigating influences on switching attention to task-unrelated imagery and thought. Consciousness and Cognition, 4, 1–21.

Grodsky, A., & Giambra, L. M. (1990–1991). The consistency across vigilance and reading tasks of individual differences in the occurrence of task-unrelated and task-related images and thoughts. Imagination, Cognition & Personality, 10, 39–52.

Hancock, P. A. (2013). In search of vigilance: the problem of iatrogenically created psychological phenomena. American Psychologist, 68, 97–109.

Hayes, A. F. (2012), “PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling”, white paper, The Ohio State University. http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2017.

Hayes, A. F., & Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis does method really matter? Psychological Science, 24, 1918–1927.

Kane, M. J., Brown, L. E., McVay, J. C., Silvia, P. J., Myin-Germeys, I., & Kwapil, T. R. (2007). For whom the mind wanders, and when: an experience-sampling study of working memory and executive control in daily life. Psychological Science, 18, 614–621.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Klinger, E. (1971). Structure and functions of fantasy. New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Klinger, E. (1999). Thought flow: Properties and mechanisms underlying shifts in content. In J. A. Singer & P. Salovey (Eds.), At play in the fields of consciousness: Essays in honor of Jerome L. Singer (pp. 29–50). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Klinger, E. (2009). Daydreaming and fantasizing: Thought flow and motivation. In K. D. Markman, W. M. P. Klein, & J. A. Suhr (Eds.), Handbook of imagination and mental simulation (pp. 225–239). New York: Psychology Press.

Klinger, E., Barta, S. G., & Maxeiner, M. E. (1980). Motivational correlates of thought content frequency and commitment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1222–1237.

McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2010). Does mind-wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2006) and Watkins (2008). Psychological Bulletin, 136, 188–197.

McVay, J. C., Kane, M. J., & Kwapil, T. R. (2009). Tracking the train of thought from the laboratory into everyday life: an experience-sampling study of mind-wandering across controlled and ecological contexts. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 16, 857–863.

Mooneyham, B. W., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). The costs and benefits of mind-wandering: a review. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie Expérimentale, 67, 11–18.

Mowlem, F. D., Skirrow, C., Reid, P., Maltezos, S., Nijjar, S. K., Merwood, A., & Asherson, P. (2016). Validation of the mind excessively wandering scale and the relationship of mind-wandering to impairment in adult ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. doi:10.1177/1087054716651927.

Mrazek, M. D., Franklin, M. S., Phillips, D. T., Baird, B., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind-wandering. Psychological Science, 24, 776–781.

Mrazek, M. D., Smallwood, J., Franklin, M. S., Chin, J. M., Baird, B., & Schooler, J. W. (2012a). The role of mind-wandering in measurements of general aptitude. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141, 788–798.

Mrazek, M. D., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2012b). Mindfulness and mind-wandering: finding convergence through opposing constructs. Emotion, 12, 442–448.

Phillips, N. E., Mills, C., D’Mello, S., & Risko, E. F. (2016). On the influence of re-reading on mind wandering. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. doi:10.1080/17470218.2015.1107109.

Robison, M. K., & Unsworth, N. (2015). Working memory capacity offers resistance to mind-wandering and external distraction in a context-specific manner. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29, 680–690.

Seli, P., Carriere, J. S., Levene, M., & Smilek, D. (2013a). How few and far between? Examining the effects of probe rate on self-reported mind wandering. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 430.

Seli, P., Carriere, J. S., Thomson, D. R., Cheyne, J. A., Martens, K. A. E., & Smilek, D. (2014). Restless mind, restless body. Journal of Experimental Psychology, Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40, 660.

Seli, P., Cheyne, J. A., & Smilek, D. (2013b). Wandering minds and wavering rhythms: Linking mind-wandering and behavioral variability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 39, 1–5.

Seli, P., Cheyne, J. A., Xu, M., Purdon, C., & Smilek, D. (2015a). Motivation, intentionality, and mind-wandering: Implications for assessments of task-unrelated thought. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. doi:10.1037/xlm0000116.

Seli, P., Jonker, T. R., Cheyne, J. A., Cortes, K., & Smilek, D. (2015b). Can research participants comment authoritatively on the validity of their self-reports of mind-wandering and task engagement? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 41, 703–709.

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., Smilek, D., & Schacter, D. L. (2016). Mind-wandering with and without intention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20, 605–617.

Seli, P., Smallwood, J., Cheyne, J. A., & Smilek, D. (2015c). On the relation of mind-wandering and ADHD symptomatology. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. doi:10.3758/s13423-014-0793-0.

Seli, P., Wammes, J. D., Risko, E. F., & Smilek, D. (2015d). On the relation between motivation and retention in educational contexts: The role of intentional and unintentional mind-wandering. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. doi:10.3758/s13423-015-0979-0.

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2012). A 21-word solution. Dialogue: The Official Newsletter of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, 26, 4–7.

Smallwood, J. M., Baracaia, S. F., Lowe, M., & Obonsawin, M. (2003). Task unrelated thought whilst encoding information. Consciousness and Cognition, 12, 452–484.

Smallwood, J., McSpadden, M., & Schooler, J. W. (2007). The lights are on but no one’s home: meta-awareness and the decoupling of attention when the mind wanders. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 14, 527–533.

Szpunar, K. K., Khan, N. Y., & Schacter, D. L. (2013). Interpolated memory tests reduce mind wandering and improve learning of online lectures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(16), 6313–6317

Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16, 213–225.

Unsworth, N., & McMillan, B. D. (2013). Mind-wandering and reading comprehension: examining the roles of working memory capacity, interest, motivation, and topic experience. Journal of Experimental Psychology, Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 832–842.

Vinski, M. T., & Watter, S. (2012). Priming honesty reduces subjective bias in self-report measures of mind-wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 21, 451–455.

Wammes, J. D., Seli, P., Cheyne, J. A., Boucher, P. O., & Smilek, D. (2016). Mind-wandering during lectures II: Relation to academic performance. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 2, 33–48.

Yanko, M. R., & Spalek, T. M. (2013). Driving with the wandering mind: the effect that mind-wandering has on driving performance. Human Factors, 56, 260–269.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Grant to D. Smilek, and by an NSERC Post-Doctoral Fellowship to P. Seli. We would like to extend our thanks to Brandon Ralph for his help with data collection.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Grant (Grant number 06459) to Daniel Smilek.

Conflict of interest

Paul Seli declares that he has no conflict of interest. Daniel L. Schacter declares that he has no conflict of interest. Evan F. Risko declares that he has no conflict of interest. Daniel Smilek declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seli, P., Schacter, D.L., Risko, E.F. et al. Increasing participant motivation reduces rates of intentional and unintentional mind wandering. Psychological Research 83, 1057–1069 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-017-0914-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-017-0914-2