Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine whether increased expression of SUR2A, a regulatory subunit of sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels, improves adaptation to physical stress and regulates cardiac electrophysiology in physical stress. All experiments have been done on transgenic mice in which SUR2A expression was controlled by cytomegalovirus immediate-early (CMV) promoter (SUR2A) and their littermate wild-type controls (WT). The levels of mRNA in heart tissue were measured by real-time RT-PCR. Electrocardiogram (ECG) was monitored with telemetry. The physical adaptation to stress was elucidated using treadmill. We have found that SUR2A mice express 8.34 ± 0.20 times more myocardial SUR2A mRNA than WT (n = 8–18). The tolerated workload on exercise stress test was more than twofold higher in SUR2A than in WT (n = 5–7; P = 0.01). The pattern of Q-T interval from the beginning of the exercise test until drop point was as follows in the wild type: (1) increase in Q-T interval, (2) decrease in Q-T interval, (3) steady stage with a further decrease in Q-T interval, and (4) a sharp increase in Q-T interval. The pattern of Q-T interval was different in transgenic mice and the following stages have been observed: (1) increase in Q-T interval, (2) decrease in Q-T interval, and (3) prolonged steady-state stage with a slight decrease in Q-T interval. In SUR2A mice, no stage 4 (a sharp increase in Q-T interval) was observed. Based on the obtained results, we conclude that an increase in the expression of SUR2A improves adaptation to physical stress and physical endurance by increasing the number of sarcolemmal KATP channels and, by virtue of their channel activity, improving Ca2+ homeostasis in the heart.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels are heteromultimers composed of, at least, two distinct subunits. The pore-forming inwardly rectifying K+ channel core, Kir6.2, is primarily responsible for K+ permeance, whereas the regulatory subunit, also known as the sulfonylurea receptor, or SUR2A has been implicated in ligand-dependent channel gating. More recently, it has been suggested that the sarcolemmal KATP channel protein complex may be composed of more proteins than just Kir6.2 and SUR2A, including enzymes regulating intracellular ATP levels and glycolysis [11]. It has been suggested that SUR2A is a rate-limiting factor in assembling sarcolemmal KATP channels and that the level of this protein regulates the level of fully assembled KATP channels [7].

Sarcolemmal KATP channels have been shown to play a crucial role in ischemic preconditioning and myocardial resistance to ischemia [11, 18, 20]. While ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality [17], it does not per se explain the preservation of KATP channels through evolution [7]. We have previously shown that and increase in SUR2A and consequent increase in KATP channel levels increase physical endurance and prolong lifespan [15, 22] while decreased SUR2A levels decrease cellular resistance to metabolic stress [5]. However, no connection between cardiac electrophysiology and improved adaptation to physical stress in mice overexpressing SUR2A has been made so far. In fact, it is yet unknown whether increased expression of SUR2A and the number of KATP channels affect cardiac electrophysiology at all.

Sarcolemmal KATP channels are normally closed under physiological conditions to be open in ischemia [7]. The role that this channel plays is yet not fully understood. Therefore, we have decided to take advantage of the phenotype with increased expression of SUR2A [3, 19] and to test whether increase of SUR2A would have any consequence on cardiac electrophysiology during exercise stress.

Methods

SUR2A mice

All experiments have been done on male mice overexpressing SUR2A (SUR2A mice) and their littermate controls (WT). Generation, breeding, and genotyping of these mice have previously been described in detail [3, 19]. All experiments conform to the Home Office Regulations in the UK. The experiments have been done under the authority of Project Licences 60/3152 and 60/3925 and mice were sacrificed, when required, by cervical dislocation constituting a Schedule 1 procedure under UK home office regulations.

Real-time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described previously using the same primers [3]. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from the cardiac ventricular tissue of transgenic and wild-type mice using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Extracted RNA was further purified with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK); the specific primers for mouse SUR2A, Kir6.2, Kir6.1, SUR1, and SUR2B and all stages of real-time RT-PCR were applied as described in ref. [3]. To determine relative mRNA expression (normalized to the wild type), we have used glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a control gene. The relative expression ratio(R) of a gene encoding SUR2A is calculated using equation R = (EK)ΔCPk(WT-TG)/(ER)ΔCPR(WT-TG) where EK is the real-time PCR efficiency of SUR2A gene transcript, ER is the real-time PCR efficiency of a reference gene, ΔCPK is the crossing point deviation of wild-type transgene of SUR2A gene transcript, and ΔCPR is the crossing point deviation of wild-type transgene of a reference gene transcript.

Telemetry

Telemetry radiotransmitters (ETA-F20, Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN, USA) were implanted in the peritoneum, and leads were tunneled s.c. in a lead II configuration under isoflurane anesthesia as described in Burgess et al. [1]. Reference points of ECG data were measured as depicted in Fig. 1. Corrected for heart rate, the Q-T interval (QTc) was calculated by using the Mitchell transformation [QTc = QT/(RR/100)0.5], where RR (in millisecond) is the interval between previous and current R wave [14].

Treadmill test

A six-lane treadmill (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, Ohio) was used to perform treadmill tests and determine energy expenditure as described in ref. [19]. The treadmill endurance test consisted of a step-wise increase in velocity over time at a constant incline. The inability to continue with physical activity was determined by the animal being unable to continue test irrespective of encouragement by electric shock (Fig. 2). Energy expenditure was defined as the sum of kinetic (Ek = m.v2/2) and potential energy (Ep = m.g.v.t.sinφ), where m is the animal mass, v is the running velocity, g is the acceleration due to gravity, t is the time elapsed at a given protocol level, and φ is the angle of incline. Energy expenditure was calculated for each time interval during the treadmill endurance test.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Sheep anti-Kir6.2 and anti-SUR2 antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation and Western blotting respectively (described in refs. [3, 19]). Sarcolemmal cardiac fraction was obtained as described previously [3] and 40 μg of the epitope-specific Kir6.2 antibody was pre-bound to Protein-G Sepharose beads and used to immunoprecipitate from 50 μg of sarcolemmal fraction protein extract. The pellets of this precipitation were run on SDS polyacrylamide gels for Western analysis. Western blot probing was performed using 1/1000 dilutions of anti-SUR2 antibody and detection was achieved using Protein-G HRP and ECL reagents. The band intensities were analyzed using the QuantiScan software.

Isolation of single cardiomyocytes

Ventricular cardiomyocytes were dissociated from the mouse using an established enzymatic procedure as we previously described numerous times [3, 19, 21]. In brief, hearts were retrogradely perfused (at 37 °C) with medium 199, followed by Ca2+-EGTA-buffered low-Ca2+ medium (pCa = 7), and finally low-Ca2+ medium containing pronase E (8 mg per 100 ml), proteinase K (1.7 mg per 100 ml), bovine albumin (0.1 g per 100 ml, fraction V), and 200 μM CaCl2. Ventricles were cut into fragments in the low-Ca2+ medium enriched with 200 μM CaCl2 and cells were isolated by stirring the tissue (at 37 °C) in a solution containing pronase E and proteinase K supplemented with collagenase (5 mg per 10 ml).

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+

Intracellular Ca2+ in the absence and presence of isoprenaline (500 nM)/glibenclamide (10 μM) was measured using fluo-3 and laser confocal microscopy as previously described [21, 22]. In brief, ventricular cardiomyocytes were loaded with 3.5 μM of fluo-3 acetoxymethyl ester (Fluo-3AM) and transferred to an experimental chamber mounted on the stage of a Zeiss LSM-510 laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM-510, Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) filled up with Tyrode’s solution (136.5 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.53 mM MgCl2, 5.5 mM Glucose, and 5.5 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4) and paced to beat by field stimulation (parameters of the stimulation, 5–20 mV depending on cellular threshold, 5 ms, 0.5 Hz). Intracellular Ca2+ was imaged using Ar/UV laser to “excite” the dye at 488 nm. Emission light by photomultiplier tubes was detected at 520 nm. The parameters of image acquisition were similar for all examined cells (mid-cell section thickness was 1 μm and gain was set always at 700 arbitrary units). Images were acquired, viewed, and analyzed using Zeiss Image Examiner Software. Only beating rod-shaped cells with clear striations were used for experimentation.

Measurement of action potential

Sarcolemmal membrane potential was measured in cardiomyocytes in the absence and presence of isoprenaline (500 nM)/glibenclamide (10 μM) using di-8-ANEPPS and laser confocal microscopy as previously described [3, 21]. Cardiomyocytes were loaded with di-8-ANEPPS according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and the sarcolemma imaged using laser confocal microscopy in line-scan mode (LSM-510, Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany). Cells were stimulated as described in section “Measurement of intracellular Ca2+”and scanned under control conditions and then exposed to isoprenaline or isoprenaline/glibenclamide. Fluorescence was detected at 488-nM excitation wavelength and emission was captured at > 505 nM.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M, with n representing the number of analyzed mice for all in vivo and biochemical experiments and the number of cells for all cellular experiments (no more than 2 cells have been done from the same mouse). Mean values were compared by Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney rank sum test where appropriate using SigmaStat program (Jandel Scientific, Chicago, IL). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of KATP channel-forming subunits in wild-type and SUR2A mice

We have analyzed the levels of SUR2A mRNA in wild-type mice and SUR2A mice. We have confirmed that SUR2A mice had significantly increased mRNA levels of SUR2A (cycling threshold was 29.2 ± 0.6 in wild-type and 26.9 ± 0.3 in transgenics, n = 8–18, P < 0.01; Fig. 3). No statistically significant difference was observed in mRNA levels of other KATP channel-forming subunits (Fig. 3). Transgenic mice had 8.34 ± 0.80 times more SUR2A mRNA than the wild type in the heart (Fig. 3). In addition to that, we probed anti-Kir6.2 immunoprecipitate of sarcolemmal fraction with anti-SUR2 antibody, which is a strategy used to measure only those Kir6.2 and SUR2A subunits that physically assemble to form a channel. Western blot has demonstrated that the levels of SUR2 protein were increased in sarcolemma in SUR2A mice when compared with those in WT mice

Levels of sarcolemmal KATP channel subunits in wild-type and SUR2A hearts. a Representative progress curves for the real-time PCR amplification of SUR2A cDNA (left panel) from wild-type (WT) and SUR2A (SUR2A) hearts and a corresponding bar graph (right panel) showing cycle threshold for the real-time PCR amplification of SUR2A (n = 8–18). *P < 0.01. b Bar graphs showing cycle threshold for the real-time PCR amplification of SUR2B, SUR1, Kir6.1, and Kir6.2 from wild-type (WT) and SUR2A (SUR2A) mice. Each bar represents mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8–18). c Level of KATP channel subunits mRNA normalized to the wild type. Each bar represents mean ± SEM (n = 8–18). d Bar graph depicting bend intensity of Western blotting of anti-Kir6.2 immunoprecipitate from WT and SUR2A sarcolemmal membrane fraction and corresponding original blots in the inset. Each bar represents mean ± SEM (n = 3–4) (*P < 0.05)

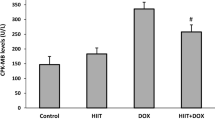

Treadmill test in wild-type and SUR2A mice

Under the exercise-stress test, SUR2A mice performed at a significantly increased level than the littermate controls (Fig. 4). The tolerated workload, a parameter that incorporates time of effort with speed and incline of the treadmill, was more than twofold higher in transgenic mice (n = 7) compared with the wild-type animals (n = 5, P = 0.01; Fig. 4). On average, transgenic mice were able to run for 1461 ± 279 m on a treadmill (n = 7), while wild-type mice have dropped-out after 472 ± 59 m (n = 5; Fig. 4). This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.01).

Q-T interval during treadmill test

Q-T interval reflects the duration of the action potential [14], while the duration of action potential is shortened by the opening of sarcolemmal KATP channels [7]. Therefore, we have examined Q-T interval during the treadmill test on 4 WT and 4 SUR2A mice. The pattern of Q-T interval from the beginning of the test until drop point was as follows in the wild type: (1) increase in Q-T interval, (2) decrease in Q-T interval, (3) steady stage with a further decrease in Q-T interval, (4) sharp increase in Q-T interval (Fig. 5). The pattern of Q-T interval was different in transgenic mice and the following stages have been observed: (1) increase in Q-T interval, (2) decrease in Q-T interval, (3) prolonged steady-state stage with a slight decrease in Q-T interval (Fig. 5). In SUR2A mice, no stage 4 (a sharp increase in Q-T interval) was observed. A heart rate just prior to the treadmill test did not differ between and was not different between phenotypes (Fig. 6). In both phenotypes, there was an increase in heart rate in response to treadmill test and there was no statistically significant difference between phenotypes in heart rate during the test (Fig. 6). Heart rate 10 min after the test was not different between the two phenotypes. However, the SUR2A mice that were used for these telemetric measurements spent significantly more time on treadmill than their WT counterparts (2787 ± 306 s for WT and 4387 ± 470 s for SUR2A mice, n = 4 for each, P = 0.029).

ECG during treadmill stress test. a An example of QRST complex changes by treadmill exercise stress test in wild-type mice and corresponding graph describing Q-T interval during the stress test (A1). Each bar represents mean ± SEM (n = 4). b An example of QRST complex changes during treadmill exercise stress test in SUR2A mice and corresponding graph describing Q-T interval during the stress test (B1). Each bar represents mean ± SEM (n = 4). c Graph showing Q-T interval in wild-type (WT) and SUR2A (SUR2A) mice in advanced stages of treadmill stress test. Each bar represents mean ± SEM (n = 4)

Action potential and intracellular Ca2+ in response to β-adrenoceptor activation

If observed differences in ECG were a consequence of different responses of KATP channels to β-adrenoceptor stimulation, it was logical to expect that evidence of such difference could be observed at the cellular level. Action potential duration did not differ between phenotypes and was similar at point 0 and after 30 min under control conditions (Fig. 7a). When exposed to isoprenaline (500 nM), the action potential was non-significantly prolonged in WT (Fig. 7b). In contrast, action potential was significantly shortened by 500 nM isoprenaline (P < 0.001; n = 7–14, Fig. 7b) in SUR2A mice. This effect of isoprenaline (500 nM) was blocked by a non-selective KATP antagonist glibenclamide (10 μM; Fig. 7c). The shortening of action potential in SUR2A mice was associated with prevention of Ca2+ loading observed in WT cardiomyocytes (P = 0.032, n = 7–15; Fig. 7d), which could be reversed by 10 μM glibenclamide (Fig. 7d).

Membrane potential and intracellular Ca2+ in cardiomyocytes exposed to isoprenaline. a, b Action potential duration in wild-type (WT) and SUR2A (SUR2A) cardiomyocytes in the absence (a) and presence (b) of 500 nM isoprenaline. Each bar represents mean ± SEM (n = 7–14). Inset in b depicts original action potential recording corresponding to b (*P < 0.05). c Action potential duration in SUR2A cardiomyocytes in the absence and presence of 500 nM isoprenaline plus glibenclamide (10 μM). Each bar represents mean ± SEM (n = 7–12). d Fluo-3 fluorescence in WT and SUR2A cardiomyocytes after 10-min-long exposure to isoprenaline (500 nM). Each bar represents mean ± SEM (n = 7–15). Inset in d depicts original fluo-3 fluorescence recording of a SUR2A cardiomyocyte exposed to isoprenaline (500 nM) in the absence and presence of glibenclamide (GLB; 10 μM) (*P < 0.05)

Discussion

In the present study, we have shown that SUR2A-mediated increase in physical endurance is associated with shortening of cardiac action potential during physical stress.

The general adaptation syndrome is a ubiquitous reaction essential for surviving under conditions of stress such as exertion or fear. It is mediated primarily by a catecholamine surge, and this syndrome generates acute changes in physiological and biochemical functions, which, in turn, improve bodily performance [2]. We have previously demonstrated that non-targeted increased expression of SUR2A generates mice that are characterized by increased physical endurance [19] and that cardiomyocytes with a high level of SUR2A handle Ca2+ homeostasis better in response to β-adrenoceptor agonist in comparison with cardiomyocytes containing physiological levels of SUR2A [22]. An increase in SUR2A increases the number of fully assembled KATP channels [3, 19], which, in turn, leads to faster onset of channel opening in ischemia and increased level of subsarcolemmal ATP [3, 4], both of which foster cardioprotection. In the present study, we confirmed these previous findings and demonstrated that an increased level of SUR2A increases the number of assembled KATP channels, which, in turn, results in more pronounced KATP channel activation and improved Ca2+ homeostasis under conditions of metabolic stress.

It has been recently suggested that β-adrenergic stimulation of isolated cardiomyocytes from rats subjected to chronic exercise was associated with shortening of action potential due to activation of sarcolemmal KATP channels [23]. However, the effect of β-adrenoceptor activation on KATP channels’ activity is complex and might depend on many factors. Few decades ago, it has been described that isoprenaline, a β-receptor agonist, when applied in vitro inhibits pre-activated sarcolemmal KATP channels [9] and a signaling link between β-adrenoceptors and KATP channels in non-cardiac tissues has been also described [10]. The regulation of sarcolemmal KATP channels’ activity is yet to be fully understood as it is controlled by the complex interaction of potentially linked intracellular signaling pathways. In addition to ATP, it has been suggested that the activity of these channels may be regulated by other nucleotides, intracellular pH, lactate, cytoskeleton, protein kinase C, and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate and by the operative condition of the channel itself [7]. An increase in the number of sarcolemmal KATP channels increases the probability of the channel opening, at least in cells that are metabolically challenged [4, 12, 21]. Indeed, we have observed Q-T interval shortening in SUR2A mice, while Q-T prolongation in WT mice suggesting that increased numbers of sarcolemmal KATP channels during treadmill exercise resulted in higher probability of opening of these channels, which, in turn, seems to mediate cardiac adaptation to physical stress.

It has been shown that increased expression of SUR2A increases physical endurance over physiological levels [19, 22]. This suggests that the number of sarcolemmal KATP channels in the heart is an important determinant of cardiovascular response to physical stress. The underlying mechanism of the sarcolemmal KATP channel–mediated regulation of physical endurance has been proposed to involve the opening of these channels and improvement of Ca2+ homeostasis in the heart [22]. When monitoring ECG during the treadmill test, we have noticed a previously unrecognized pattern of ECG changes. A stage-like pattern of Q-T interval would confirm a complexity of the regulation of the cardiovascular system during different degrees of physical stress and would be in accord with the activation of neuronal and hormonal stress systems [8, 13]. It is well established for decades that physical stress is associated with the shortening of Q-T interval [6], but we have here found that there is an initial brief increase in the Q-T interval preceding its shortening. In the wild type, when physical activity has become unsustainable, a sharp increase in Q-T interval was observed, which did not happen in SUR2A mice. An inhibition of an increase in the Q-T interval is consistent with the sarcolemmal KATP channels counteracting stress-induced prolongation of the action potential during stress as we observed previously at the cellular level [21].

The shortening of the action potential leads to decreased Ca2+ influx and prevention of intracellular Ca2+ loading, which is very well known to be the main cause of impaired cardiac function during metabolic stress [16]. In cardiomyocytes with physiological levels of SUR2A, there is a slow buildup of intracellular Ca2+ when exposed to β-adrenoceptor stimulation [22; present study]. An increased expression of SUR2A prevents Ca2+ buildup, showing that upregulation of SUR2A improves Ca2+ homeostasis in cardiac cells. This is compatible with the hypothesis that increased number of sarcolemmal KATP channels protects against intracellular Ca2+ loading by shortening ventricular action potentials, which, in turn, improves cardiac response to increased metabolic demands and improves adaptation to physical stress and physical endurance. In the present study, we provided further evidence at the cellular level to support the role of KATP channels in the regulation of action potential and Ca2+ homeostasis and demonstrated that an increase in these channels’ number improves cellular resistance to β-adreneceptor-induced metabolic stress.

In conclusion, this study has shown that increased expression of SUR2A regulates cardiac physiology and improves adaptation to physical stress. The underlying mechanism is likely to involve an increase in the number of sarcolemmal KATP channels, shortening of action potential, and improved cardiac Ca2+ homeostasis.

References

Burgess K, Jovanović S, Sudhir R, Jovanović A (2019) Area under the curve analysis of blood pressure reveals increased spontaneous locomotor activity in SPAK knock in mice: relevance for hypotension induced by SPAK inhibition? Physiol Rep 7:e13997. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13997

Cunanan AJ, DeWeese BH, Wagle JP, Carroll KM, Sausaman R, Hornsby WG, Haff GG, Triplett NT, Pierce KC, Stone MH (2018) The general adaptation syndrome: a foundation for the concept of periodization. Sports Med 48:787–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0855-3

Du Q, Jovanović S, Clelland A, Sukhodub A, Budas GR, Phelan K, Murray-Tait V, Malone L, Jovanović A (2006) Overexpression of SUR2A generates a cardiac phenotype resistant to ischaemia. FASEB J 20:1131–1141. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.05-5483com

Du Q, Jovanović S, Sukhodub A, Jovanović A (2010) Infection with AV-SUR2A protects H9C2 cells against metabolic stress: a mechanism of SUR2A-mediated cytoprotection independent from the KATP channels activity. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res 1803:405–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.01.018

Du Q, Jovanović S, Sukhodub A, Ngoi YS, Lal A, Zheleva M, Jovanović A (2018) Insulin down-regulates cardioprotective SUR2A in the heart-derived H9c2 cells: a possible explanation for some adverse effects of insulin therapy. Biochem Biophys Rep 16:12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2018.08.005

Fananapazir D, Bennett DH, Faragher EB (1983) Contribution of heart rate to QT interval shortening during exercise. Eur Heart J 4:265–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061458

Foster MN, Coetzee WA (2016) KATP channels in the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev 96:177–252. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00003.2015

Hackney AH, Walz EA (2013) Hormonal adaptation and the stress of exercise training: the role of glucocorticoids. Trends Sport Sci 20:165–171

Heath BM, Terrar DA (1994) Effect of glibenclamide, forskolin, and isoprenaline on the parallel activation of KATP and reduction of IK by cromakalim in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 28:818–822. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/28.6.818

Jacobus AP, Rodrigues DO, Borba PF, Loss ES, Wassermann GF (2005) Isoproterenol opens K+(ATP) channels via beta2-adrenoceptor-linked mechanism in Sertoli cells from immature rats. Horm Metab Res 37:198–204. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-861414

Jovanović A (2018) Cardioprotective signalling: Ppast, present and future. Eur J Pharmacol 833:314–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.06.029

Jovanović S, Ballantyne T, Du Q, Blagojević M, Jovanović A (2016) Phenylephrine preconditioning in embryonic heart H9c2 cells is mediated by up-regulation of SUR2B/Kir6.2: a first evidence for functional role of SUR2B in sarcolemmal KATP channels and cardioprotection. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 70:23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2015.10.029

Mastorakis G, Pavlatou M, Diamanti-Kanderakis E, Chrousos GP (2005) Exercise and the stress system. Hormones 4:73–89

Mitchell GF, Jeron A, Koren G (1998) Measurement of heart rate and Q-T interval in the conscious mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274:H747–H751. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.3.H747

Mohammed Abdul KS, Jovanović S, Jovanović A (2017) Exposure to 15% oxygen in vivo up-regulates cardioprotective SUR2A without affecting ERK1/2 and Akt: a crucial role for AMPK. J Cell Mol Med 21:1342–1350. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13064

Murphy E, Steenbergen C (2008) Ion transport and energetics during cell death and protection. Physiology 23:115–123. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.00044.2007

Sanchis-Gomar F, Perez-Quilis C, Leischik R, Lucia A (2016) Epidemiology of coronary heart disease and acute coronary syndrome. Ann Transl Med 4:256. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2016.06.33

Sinha S, Du Q, Jovanović S, Sukhodub A, Jovanović A (2019) Pyrazinamide may possess cardioprotective properties. J Antibiotics 72:714–717. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41429-019-0202-z

Sudhir R, Sukhodub A, Du Q, Jovanović S, Jovanović A (2011) Ageing-induced decline in physical endurance in mice is associated with decrease in cardiac SUR2A and increase in cardiac susceptibility to metabolic stress: therapeutic Prospects for up-regulation of SUR2A. Biogerontology 12:147–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-010-9306-3

Sukhodub A, Du Q, Jovanović S, Jovanović A (2010) Nicotinamide-rich diet protects the heart against ischaemia-reperfusion in mice: a crucial role for cardiac SUR2A. Pharmacol Res. 61:564–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2010.01.008

Sukhodub A, Jovanović S, Du Q, Budas GR, Clelland A, Shen M, Sakamoto K, Tian R, Jovanović A (2007) AMP-activated protein kinase mediates preconditioning in cardiomyocytes by regulating activity and trafficking of sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive K+ channels. J Cell Physiol 210:224–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.20862

Sukhodub A, Sudhir R, Du Q, Jovanović S, Reyes S, Jovanović A (2011) Nicotinamide-rich diet improves physical endurance by upregulating SUR2A in the heart. J Cell Mol Med 15:1703–1712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01156.x

Wang X, Fitts RH (2017) Ventricular action potential adaptation to regular exercise: role of β-adrenergic and KATP channel function. J Appl Physiol 123(1985):285–296. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00197.2017

Funding

This research was supported by the British Heart Foundation (grant nos. PG/11/106/29235 and PG/15/28/31384).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All experiments conform to the Home Office Regulations in the UK. The experiments have been done under the authority of Project Licences 60/3152 and 60/3925.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sudhir, R., Du, Q., Sukhodub, A. et al. Improved adaptation to physical stress in mice overexpressing SUR2A is associated with changes in the pattern of Q-T interval. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 472, 683–691 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-020-02401-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-020-02401-5