Abstract

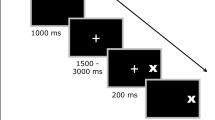

While impairments in executive functions have been well established in major depressive disorder (MDD), specific deficits in proactive control have scarcely been studied so far. Proactive control refers to cognitive processes during anticipation of a behaviorally relevant event that facilitate readiness to react. In this study, cerebral blood flow responses were investigated in MDD patients during a precued antisaccade task requiring preparatory attention and proactive inhibition. Using functional transcranial Doppler sonography, blood flow velocities in the middle cerebral arteries of both hemispheres were recorded in 40 MDD patients and 40 healthy controls. In the task, a target appeared left or right of the fixation point 5 s after a cuing stimulus; subjects had to move their gaze to the target (prosaccade) or its mirror image position (antisaccade). Video-based eye-tracking was applied for ocular recording. A right dominant blood flow increase arose during prosaccade and antisaccade preparation, which was smaller in MDD patients than controls. Patients exhibited a higher error rate than controls for antisaccades but not prosaccades. The smaller blood flow response may reflect blunted anticipatory activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal and inferior parietal cortices in MDD. The patients’ increased antisaccade error rate suggests deficient inhibitory control. The findings support the notion of impairments in proactive control in MDD, which are clinically relevant as they may contribute to the deficits in cognition and behavioral regulation that characterize the disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Values at the beginning of the task period (time 0) were slightly higher in MDD patients than controls, which may be ascribed to spontaneous fluctuations of flow velocities at baseline.

References

Aron AR (2011) From reactive to proactive and selective control: developing a richer model for stopping inappropriate responses. Biol Psychiat 69:e55–e68

Braver TS (2012) The variable nature of cognitive control: a dual mechanisms framework. Trends Cogn Sci 16:106–113

Barch DM, Carter CS, Braver TS, Sabb FW, MacDonald A, Noll DC, Cohen JD (2001) Selective deficits in prefrontal cortex function in medication-naive patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiat 58:280–288

Burgess GC, Depue BE, Ruzic L, Willcutt EG, Du YP, Banich MT (2010) Attentional control activation relates to working memory in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiat 67:632–640

Braver TS, Gray JR, Burgess GC (2007) Explaining the many varieties of working memory variation: dual mechanisms of cognitive control. In: Conway ARA, Jarrold C, Kane MJ, Miyake A, Towse JN (eds) Variation in working memory. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 76–106

Hoffmann A, Ettinger U, Reyes del Paso GA, Duschek S (2017) Executive function and cardiac autonomic regulation in depressive disorders. Brain Cog 118:108–117

Porter RJ, Bourke C, Gallagher P (2007) Neuropsychological impairment in major depression: Its nature, origin and clinical significance. Aust NZ J Psychiat 41:115–128

Snyder HR (2013) Major depressive disorder is associated with broad impairments on neuropsychological measures of executive function: a meta-analysis and review. Psychol Bull 139:81–132

Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kalayam B, Kakuma T, Gabrielle M, Sirey JA, Hull J (2000) Executive dysfunction and long-term outcomes of geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiat 57:285–290

Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S (2006) Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiat Res 145:39–48

Majer M, Ising M, Künzel H, Binder EB, Holsboer F, Modell S, Zihl J (2004) Impaired divided attention predicts delayed response and risk to relapse in subjects with depressive disorders. Psychol Med 34:1453–1463

Pu S, Yamada T, Yokoyama K, Matsumura H, Kobayashi H, Sasaki N, Mitanic H, Adachic A, Kanekoa K, Nakagome K (2011) A multi-channel near-infrared spectroscopy study of prefrontal cortex activation during working memory task in major depressive disorder. Neurosci Res 70:91–97

Uemura K, Shimada H, Doi T, Makizako H, Park H, Suzuki T (2010) Depressive symptoms in older adults are associated with decreased cerebral oxygenation of the prefrontal cortex during a trail-making test. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 59:422–428

Yüksel C, Öngür D (2010) Magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of glutamate-related abnormalities in mood disorders. Biol Psychiat 68:785–794

Vanderhasselt MA, De Raedt R, Dillon DG, Dutra SJ, Brooks N, Pizzagalli DA (2012) Decreased cognitive control in response to negative information in patients with remitted depression: an event-related potential study. J Psychiatr Neurosci 37:250–258

West R, Choi P, Travers S (2010) The influence of negative affect on the neural correlates of cognitive control. Int J Psychophysiol 76:107–117

Ashton H, Golding JF, Marsh VR, Thompson JW, Hassanyeh F, Tyrer SP (1988) Cortical evoked potentials and clinical rating scales as measures of depressive illness. Psychol Med 18:305–317

Giedke H, Heimann H (1987) Psychophysiological aspects of depressive syndromes. Pharmacopsychiatry 20:177–180

Birbaumer N, Elbert T, Canavan AGM, Rockstroh B (1990) Slow potentials of the cerebral cortex and behavior. Physiol Rev 70:1–41

Fischer B, Weber H (1996) Effects of procues on error rate and reaction times of antisaccades in human subjects. Exp Brain Res 109:507–512

Hallett PE (1978) Primary and secondary saccades to goals defined by instructions. Vision Res 18:1279–1296

Antoniades C, Ettinger U, Gaymard B, Gilchrist I, Kristjánsson A, Kennard C, Leighg RJ, Noorani I, Pouget P, Smyrnis N, Tarnowski A, Zee AS, Carpenter RHS (2013) An internationally standardised antisaccade protocol. Vis Res 84:1–5

Munoz DP, Everling S (2004) Look away: the anti-saccade task and the voluntary control of eye movement. Nat Rev Neurosci 5:218–228

Meyhöfer I, Bertsch K, Esser M, Ettinger U (2016) Variance in saccadic eye movements reflects stable traits. Psychophysiology 53:566–578

Hutton SB, Ettinger U (2006) The antisaccade task as a research tool in psychopathology: a critical review. Psychophysiology 43:302–313

Johnson A, Proctor RW (2004) Attention. Theory and practice. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Posner MI, Petersen SE (1990) The attention system of the human brain. Annual Rev Neurosci 13:25–42

Ballanger B (2009) Top-down control of saccades as part of a generalized model of proactive inhibitory control. J Neurophysiol 102:2578–2580

Aaslid R, Markwalder TM, Nornes H (1982) Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in basal cerebral arteries. J Neurosurg 57:769–774

Duschek S, Schandry R (2003) Functional transcranial Doppler sonography as a tool in psychophysiological research. Psychophysiology 40:436–454

Chambers CD, Bellgrove MA, Stokes MG, Henderson TR, Garavan H, Robertson IH, Morris AP, Mattingley JB (2006) Executive “brake failure” following deactivation of human frontal lobe. J Cog Neurosci 18:444–455

Chambers CD, Garavan H, Bellgrove MA (2009) Insights into the neural basis of response inhibition from cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33:631–646

Paus T, Zatorre RJ, Hofle N, Caramanos Z, Gotman J, Petrides M, Evans AC (1997) Time-related changes in neural systems underlying attention and arousal during the performance of an auditory vigilance task. J Cog Neurosci 9:392–408

Haines DE (2004) Neuroanatomy. An Atlas of structures, sections, and systems. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Duschek S, Hoffmann A, Montoro CI, Reyes del Paso, GA, Schuepbach D, Ettinger U (2018) Cerebral blood flow modulations during preparatory attention and proactive inhibition. Biol Psychol 137:65–72

Connolly JD, Goodale MA, Menon RS, Munoz DP (2002) Human fMRI evidence for the neural correlates of preparatory set. Nat Neurosci 5:1345–1352

Hoffmann A, Montoro CI, Reyes del Paso GA, Duschek S (2018) Cerebral blood flow modulations during executive control in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 237:118–125

MacLeod CM (1991) Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: an integrative review. Psych Bull 109:163

Hoffmann A, Montoro CI, Reyes del Paso GA, Duschek S (2018) Cerebral blood flow modulations during cognitive control in major depression. Int J Psychophysiol (in press)

Caligiuri MP, Ellwanger J (2000) Motor and cognitive aspects of motor retardation in depression. J Affect Disorders 57:83–93

Pier MPBI, Hulstijn W, Sabbe BGC (2004) Differential patterns of psychomotor functioning in unmedicated melancholic and nonmelancholic depressed patients. J Psychiatr Res 38:425–435

Sabbe B, Hulstijn W, van Hoof J, Tuynman-Qua HG, Zitman F (1999) Retardation in depression: assessment by means of simple motor tasks. J Affect Disorders 55:39–44

Katsanis J, Kortenkamp S, Iacono WG, Grove WM (1997) Antisaccade performance in patients with schizophrenia and affective disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 106:468–472

Lyche P, Jonassen R, Stiles TC, Ulleberg P, Landrø NI (2001) Attentional functions in major depressive disorders with and without comorbid anxiety. Arch Clinical Neuropsychol 26:38–47

Duschek S, Schuepbach D, Schandry R (2008) Time-locked association between rapid cerebral blood flow modulation and attentional performance. Clin Neurophysiol 119:1292–1299

Duschek S, Heiss H, Schmidt FH, Werner N, Schuepbach D (2010) Interactions between systemic hemodynamics and cerebral blood flow during attentional processing. Psychophysiology 47:1159–1166

Wittchen HU, Wunderlich U, Gruschwitz S, Zaudig M (1997) SKID-I. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV. Achse I: Psychische Störungen [SCID-I. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Axis I Disorders]. Hogrefe, Göttingen

Wittchen HU, Perkonigg A (1996) DIA-X SSQ. Swets Test Services, Frankfurt a.M.

Oldfield RC (1971) The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9:97–113

Hautzinger M, Kühner C, Keller F (2006) Beck Depression Inventar II (BDI 2). Pearson Assessment & Information, Frankfurt a.M.

Ford KA, Goltz HC, Brown MRG, Everling S (2005) Neural processes associated with antisaccade task performance investigated with event-related fMRI. J Neurophysiol 94:429–440

Deppe M, Knecht S, Henningsen H, Ringelstein EB (1997) AVERAGE: a Windows® program for automated analysis of event related cerebral blood flow. J Neurosci Met 75:147–154

Montoro CI, Duschek S, Muñoz Ladrón de Guevara C, Fernández-Serrano MJ, Reyes del Paso GA (2015) Aberrant cerebral blood flow responses during cognition: Implications for the understanding of cognitive deficits in fibromyalgia. Neuropsychology 29:173–182

Reyes del Paso GA, Montoro CI, Duschek S (2015) Reaction time, cerebral blood flow, and heart rate responses in fibromyalgia: Evidence of alterations in attentional control. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 37:414–428

Pardo JV, Fox PT, Raichle ME (1991) Localization of a human system for sustained attention by positron emission tomography. Nature 349(6304):61–64

Iadecola C (2004) Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 5:347–360

Duschek S, Schandry R (2004) Cognitive performance and cerebral blood flow in essential hypotension. Psychophysiology 41:905–913

DeSouza JF, Menon RS, Everling S (2003) Preparatory set associated with pro-saccades and anti-saccades in humans investigated with event-related fMRI. J Neurophysiol 89:1016–1023

Fitzgerald PB, Laird AR, Maller J, Daskalakis ZJ (2008) A meta-analytic study of changes in brain activation in depression. Hum Brain Mapp 29:683–695

Aron AR, Fletcher PC, Bullmore ET, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (2003) Stop-signal inhibition disrupted by damage to right inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nat Neurosci 6:115–116

Rieger M, Gauggel S, Burmeister K (2003) Inhibition of ongoing responses following frontal, nonfrontal, and basal ganglia lesions. Neuropsychology 17:272–282

Swick D, Ashley V, Turken AU (2008) Left inferior frontal gyrus is critical for response inhibition. BMC Neurosci 9:102

Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Müri RM, Nyfeler T, Milea D (2005) The role of the human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in ocular motor behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1039:239–251

Ploner CJ, Gaymard BM, Rivaud-Péchoux S, Pierrot-Deseilligny C (2005) The prefrontal substrate of reflexive saccade inhibition in humans. Biol Psychiat 57:1159–1165

Liddle PF, Kiehl KA, Smith AM (2001) Event-related fMRI study of response inhibition. Hum Brain Mapp 12:100–109

Menon V, Adleman NE, White CD, Glover GH, Reiss AL (2001) Error related brain activation during a Go/NoGo response inhibition task. Hum Brain Mapp 12:131–143

Dillon DG, Wiecki T, Pechtel P, Webb C, Goer F, Murray Trivedi M, Fava M, McGrath PJ, Weissman M, Parsey R, Kurian B, Adams P, Carmody T, Weyandt S, Shores-Wilson K, Toups M, McInnis M, Oquendo MA, Cusin C, Deldin P, Bruder G, Pizzagalli DA (2015) A computational analysis of flanker interference in depression. Psychol Med 45:2333–2344

Markela-Lerenc J, Kaiser S, Fiedler P, Weisbrod M, Mundt C (2006) Stroop performance in depressive patients: a preliminary report. J Affect Disorders 94:261–267

Zetsche U, D’Avanzato C, Joormann J (2012) Depression and rumination: relation to components of inhibition. Cogn Emot 26:758–767

Stefanopoulou E, Manoharan A, Landau S, Geddes JR, Goodwin G, Frangou S (2009) Cognitive functioning in patients with affective disorders and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatr 21:336–356

Duschek S, Hadjamu M, Schandry R (2007) Enhancement of cerebral blood flow and cognitive performance due to pharmacological blood pressure elevation in chronic hypotension. Psychophysiology 44:145–153

Schuepbach D, Egger ST, Boeker H, Duschek S, Vetter S, Seifritz E, Herpertz SC (2016) Determinants of cerebral hemodynamics during the Trail Making Test in schizophrenia. Brain Cogn 109:96–104

McClintock SM, Husain MM, Greer TL, Cullum CM (2010) Association between depression severity and neurocognitive function in major depressive disorder: A review and synthesis. Neuropsychology 24:9–34

Rehse M, Bartolovic M, Baum K, Richter D, Weisbrod M, Roesch-Ely D (2016) Influence of Antipsychotic and Anticholinergic Loads on Cognitive Functions in Patients with Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research and Treatment, Article ID 8213165

Meyer JS (2018) Psychopharmacology: Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Anniversary Fund of the Austrian National Bank (project 16289). We are grateful to Angela Bair for her help with the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Board for Ethical Questions in Science of the University of Innsbruck, Austria, and, therefore, performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All participants provided written informed consent.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Access to research data

The research data of the study are available to the public via the repository Open Science Framework (OSF: osf.io/ceba8).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hoffmann, A., Ettinger, U., Montoro, C. et al. Cerebral blood flow responses during prosaccade and antisaccade preparation in major depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 269, 813–822 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-018-0956-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-018-0956-5