Abstract

Background

There are a variety of surgical techniques which can be used to treat structural nasal obstruction. Airwayplasty is a procedure, combining septoplasty, turbinate surgery, and nasal wall lateralization. The article reports the long-term result of this novel approach.

Methodology

Patients who have evidence of structural nasal obstruction were offered the option to have airwayplasty under the senior surgeon. Patients were asked to quantify the severity and the impact of their nasal obstruction using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the validated Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22) pre-operatively and post-operatively.

Results

The mean total SNOT-22 score and VAS score showed a reduction of more than 50% with significant p value at 6 and 12 months post-operatively.

Conclusions

This novel approach to nasal obstruction can provide good long-term functional results for patients suffering from nasal obstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nasal obstruction is a common complaint that can significantly impair one’s quality of life [1, 2]. It is known to affect one’s emotional function, productivity, and the ability to perform daily activities [3].

The underlying aetiology can be broadly divided into mucosal or structural cause, but in most cases, it is usually bi-factorial. Pharmacological therapy is usually used as a first line treatment to reduce mucosal inflammation and congestion of the nasal passages. However, surgical intervention may be required if there is no improvement with medical treatment, particularly if there is evidence of structural obstruction. Conventionally, procedures are aimed either to correct the laxity of the lateral nasal wall (by alarplasty) or to expand the cross-sectional area of the nasal passages (by septoplasty and turbinoplasty) [4].

More recently, a few papers described a different approach to nasal obstruction by addressing the pyriform aperture using a technique, coined as nasal wall lateralization [4,5,6].

In this article, the authors introduce a new concept termed “airwayplasty”, a procedure combining septoplasty, turbinate surgery, and nasal wall lateralization to address nasal obstruction. The results of this novel approach including the nasal wall lateralization technique are described below.

Materials and methods

Patients who were still experiencing symptom of nasal obstruction after a 6-month period of pharmacological therapy between the year 2013 and 2015 were identified prospectively from a rhinology clinic. Those who have evidence of structural obstruction were offered the option to have airwayplasty under the senior surgeon. There were no exclusion criteria.

Pre-operatively, patients were asked to quantify the severity of their nasal obstruction using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). They also completed the validated Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22) to assess their symptoms and the impact the symptoms have on their quality of life. These assessments were repeated at 3, 6, and, 12 months post-operatively as part of their long-term follow-up.

The results obtained were tabulated using Microsoft Excel 2016 and statistically analysed using the statistical software RStudio. Mean values for the individual SNOT-22 question scores, total SNOT-22 score, and the VAS scores before and after surgery were compared using the paired t test and the paired Wilcoxon non-parametric test. The p value was considered significant at p < 0.05.

Operative technique

With the patient under general anaesthesia, Moffett’s solution (2 ml cocaine 10%, 1 ml adrenaline 1 in 1000, 2 ml sodium bicarbonate 8%, and water added to 10 ml) is applied to both nasal cavities.

Septoplasty is performed first using submucosal resection technique. This is followed by outfracture of the inferior turbinates and reduction using the Abbey diathermy needle.

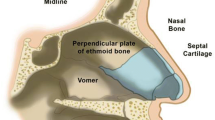

For lateralization of the nasal wall lateralization, lidocaine 2% with adrenaline 1 in 80,000 is used to infiltrate the mucosa and deep tissues over the nasal aperture superior to the attachment of the inferior turbinate. A vertical incision is then made superior to the base of inferior turbinate over the nasal process of maxilla (Fig. 1) [6]. The incision is deepened to the nasal aperture and a Freer’s dissector is used to dissect soft tissue from the nasal process of the maxilla. The bone comprising the junction of the lacrimal bone with the uncinate process, the base of the inferior turbinate, and the edge of the maxilla at the pyriform aperture is removed using a hammer and a gauge (Fig. 2) and then repositioned to prevent any alar collapse in the area [6].

The nasal mucosa in the anterior lateral nasal wall is fully preserved and then replaced. The incision is closed with absorbable sutures.

Results

A total of 28 patients were initially included in the cohort. However, after 12 months, 5 patients could no longer be contacted; hence, their data were excluded from the analysis. The final patient sample comprised of 23 patients, of which 11 were female and 12 male. The mean age was 41.3 years.

The mean total SNOT-22 score before surgery was 51.7 ± 10.3. At 6 month post-surgery, this had dropped to 19.6 ± 10.3 (62% reduction compared to before surgery, p < 0.00007) (Fig. 3). Not all of the individual components of the SNOT-22 showed similar improvement; the greatest reductions were in the “blockage/congestion of nose” (72% reduction, p < 0.0003) “need to blow nose” (72% reduction, p < 0.0002) and “ear fullness” (69% reduction, p < 0.0006) scores (Table 1).

When the patients were re-assessed at 12-month post-surgery, all the 22 components’ scores remained lower compared to their pre-operative scores. 8 out of the 22 symptoms such as “facial pain/pressure”, “lack of a good night’s sleep”, “fatigue during the day”, “reduced productivity”, and “reduced concentration” continued to improve at 12-month post-surgery. However, other symptoms including “blockage/congestion of nose”, “need to blow nose”, and “sneezing and runny nose” have a slightly higher score compared to their scores at 6-month post-surgery. Nonetheless, the mean total SNOT-22 score was 23.3 ± 8.3, representing a 54% reduction compared to before surgery (p < 0.00006).

The mean VAS score for blockage of nose had decreased from 9.0 ± 0.6 to 2.2 ± 0.9 (76% reduction, p < 0.00005) at 12 + months compared to before surgery (Fig. 4; Table 2).

Discussion

Nasal wall lateralization is a concept, first introduced by Triaca et al. [4]. It is a technique that aims to widen the pyriform aperture, which is functionally a part of the nasal valve to improve nasal airflow.

Triaca et al. lateralized the nasal wall by performing a half-moon-shaped osteotomy on the cortex of the anterior sinus and subsequently deepening the superior and inferior edges lateromedially from within the nostrils. The pyriform aperture is, therefore, substantially lateralised and broadened. Although there were no long-term nasomoteric results, 15 patients reported substantial subjective improvement post-operatively [4].

In 2015, Simmen et al. described the same procedure with slight variations. In contrast to Triaca, Simmens et al. performed this procedure endoscopically by removing the lacrimal bone that joins the uncinate process behind the lacrimal duct as well as the base of the inferior turbinate and the edge of the maxilla at the rim of the pyriform aperture. They used this technique in conjunction with pyriform turbinoplasty. Their result which was based on a simulation model showed an increase in airflow through the nasal cavity without substantially altering the normal distribution and pattern of airflow post-operatively [5].

Septoplasty is among the most frequently performed procedures for nasal obstruction. However, the improvement and success rate from this procedure alone can be variable [7]. For instance, a minor deviation of the septum may not produce a noticeable result for patients. On the contrary, septoplasty could make a difference in a severely deformed septum. However, the cause of a deviated septum is also often the reason for a less than optimal result particularly when there has been a long-term damage to cartilage or when fractures have been sustained for quite some time [7].

Another common surgical approach to nasal airway obstruction is surgery to the inferior turbinates. These techniques can be performed either by lateralising, resecting, or coagulating the turbinates. However, excessive reduction or resection of the turbinate can lead to desiccation, crusting and drying of the mucosal surface, leading to subsequent paradoxical reduction in the sensation of airflow despite improvement in airflow [8,9,10,11]. Moreover, the turbinate mucosa tends to re-hypertrophy overtime causing relapse of symptom [12].

Our results show that airwayplasty is able to provide long-term benefit to patients with nasal obstruction. Although the symptom score for “blockage/congestion of nose”, “need to blow nose”, and “sneezing and runny nose” were slightly higher at 12 months compared to their scores at 6-month post-surgery, the collection of symptoms suggested that they could be mucosal related or due to non-compliance with drug therapy.

Airwayplasty addresses the whole anatomical sino-nasal unit including the nasal inlet and valve through septoplasty, turbinoplasty, and nasal wall lateralization. Hence, the patients included in this article and whom would be suitable for airwayplasty will be those who have a combination of deviated nasal septum, hypertrophied turbinates, and narrow pyriform aperture corresponding to the internal nasal valve region.

To determine the pyriform aperture opening, the senior author would assess the lateral wall for a prominence formed by the “shoulder” of the anterior end of inferior turbinate just overlying the lacrimal system [5]. Other papers suggested that 3D computed tomography (CT) scanning could be used to measure the width of nasal aperture, but there is no consensus within the literature on what is deemed to be a normal minimum aperture [13,14,15].

By removing the bone at the junction of the lacrimal bone with the uncinate process behind the lacrimal duct, this not only results in a more substantial widening of the lateral nasal wall but also a persistent improvement of the cross-sectional area of the valve is achieved, which improves nasal function significantly.

Conclusion

Airwayplasty can provide good long-term functional results for patients suffering from nasal obstruction. The authors hope that this technique may be a valuable addition to the armament of different approaches available for nasal obstruction.

References

Akduman D, Yanılmaz M, Haksever M, Doner F, Sayar Z (2013) Patients` evaluation for the surgical management of nasal obstruction. Rhinology 51:361–367

Udaka T, Suzuki H, Kitamura T et al (2006) Relationships among nasal obstruction, daytime sleepiness, and quality of life. Laryngoscope 116:2129–2132

Shedden A (2005) Impact of nasal congestion on quality of life and work productivity in allergic rhinitis: findings from a large online survey. Treat Respir Med 4(6):439–446

Triaca A, Brusco D, Guijarro-Martínez R (2013) Nasal wall lateralization: a novel technique to improve nasal airway obstruction. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51(2):e24-5

Simmen D, Sommer F, Briner HR, Jones N, Kröger R, Hoffmann TK, Lindemann J (2015) The effect of “Pyriform Turbinoplasty” on nasal airflow using a virtual model. Rhinology 53(3):242–248

Smith W, Lowe D, Leong P (2009) Resection of pyriform aperture: a useful adjunct in nasal surgery. J Laryngol Otol 123(1):123–125

de Ru JA (2015) Septoplasty is a proven and effective procedure: an expert’s view of a burning issue. B-ENT 11(4):257–262

Lindemann J, Keck T, Wiesmiller K, Sander B, Brambs HJ, Rettinger G, Pless D (2006) A numerical simulation of intranasal air temperature during inspiration. Laryngoscope 114:1037–1041

Lindemann J, Leiacker R, Sikora T, Rettinger G, Keck T (2002) Impact of unilateral sinus surgery with resection of the turbinates via midfacial degloving on nasal air conditioning. Laryngoscope 112:2062–2066

Lindemann J, Keck T, Wiesmiller KM, Rettinger G, Brambs HJ, Pless D (2005) Numerical simulation of intranasal air flow and temperature after resection of the turbinates during inspiration. Rhinology 43:24–28

Lindemann J, Brambs HJ, Keck T, Wiesmiller KM, Rettinger G, Pless D (2005) Numerical simulation of intranasal air flow after radical sinus surgery. Am J Otol 26:175–180

Lavinsky-Wolff M, Camargo HL Jr, Barone CR et al (2013) Effect of turbinate surgery in rhinoseptoplasty on quality-of-life and acoustic rhinometry outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. Laryngoscope 123:82–89

Erdem T, Ozturan O, Erdem G, Akarcay M, Miman MC (2004) Nasal pyriform aperture stenosis in adults. Am J Rhinol 18:57–62

Hommerich CP, Riegel A (2002) Measuring of the piriform aperture in humans with 3D-SSD-CT-reconstructions. Ann Anat 184:455–459

Lee SH, Yang TY, Han GS, Kim YH, Jang TY (2008) Analysis of the nasal bone and nasal pyramid by three-dimensional computed tomography. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 265:421–424

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest from any authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, B.L.K., Peng, Y., Shamil, E. et al. Airwayplasty: long-term outcome of nasal wall lateralisation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 275, 1123–1128 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-4911-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-4911-x