Abstract

Self-assembly of amphiphilic block copolymers into polymersomes continues to be a hot topic in modern research on biomimetics. Their well-known and valued mechanical strength can be increased even further if they are cross-linked. These additional bonds prevent a collapse or disassembly of the polymersomes and open the way towards smart nanoreactors. A variety of chemistries have been applied to obtain the desired cross-linked polymersomes, and therefore, the chemical approaches performed over time will be highlighted in this mini-review. Due to the large number of studies, a selected set of photo-cross-linked and pH-sensitive polymersomes will be specifically highlighted. This system has proven to be a very potent candidate for the formation of nanoreactors and drug delivery systems, and even for the formation of functional multicompartment cell mimics.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

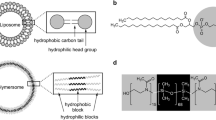

Self-assembly of amphiphilic block copolymers into nanoparticles continues to be of great interest among chemists and biologists [1,2,3]. Nanoparticles that are around 20–200 nm in size have advantages in overcoming cellular barriers; hence, they are more easily internalized into cells, which explains the large focus on smaller polymeric self-assemblies in the scientific community [4,5,6]. Among them, the so-called polymersomes, polymeric analogues of liposomes, attracted great attention due to their higher mechanical and chemical stability over liposomes. Polymersomes are also of interest due to the ability to transport or host different kinds of bio(macro)molecules. Polymersomes host hydrophilic molecules in their aqueous lumen and hydrophobic molecules within the membrane enclosing them [7, 8].

Polymersomes can be oriented towards different fields in biomedicine as they have been designed and multifunctionalized using different strategies according to the desired application. For instance, the decoration of the polymersome surface with targeting moieties allows their specific uptake by different cell lines. In order to apply polymersomes as therapeutic artificial organelles, drugs or functional enzymes are encapsulated in the vesicles, which are then delivered to the cellular environment. This is a promising strategy to increase intracellular enzyme activity, to replace malfunctioning proteins or even treat a disease (Fig. 1) [9,10,11,12,13]. Moreover, large variety of stimuli-responsive polymers have been designed, a class of “smart” polymers that can sense minimal changes in the environment (pH, light, temperature, enzymes, redox agents, ions, gas, mechanical force or electrochemistry) leading to physical or chemical structural changes in the final polymersome [12, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. These kinds of polymersomes receive internal or external stimuli to control the capture and release of drugs and chemicals and for the performance of enzymatic reactions. Also, self-regulated polymersomes have been constructed recently that show temporally programmable biocatalysis induced by a chemical fuel or systems even with autonomous movement using a biocompatible fuel [14, 20, 26,27,28]. Going a step further, multicompartment vesicles have been produced to mimic the complexity of cells even better. Due to their cell-mimicking nature, such systems are called “protocells”. The integration of molecularly crowded micro-environments into membrane-enclosed protocell models represents a step towards more realistic representations of cellular structure and organization (Fig. 1) [9,10,11,12, 19].

For nanoreactors hosting an active catalyst, membrane permeability plays an important role with regard to the applicability of the polymersomes. They should retain the catalytically active species, e.g. enzymes, inside and let only small molecules permeate through the membrane. Appropriate approaches hence need to create membranes with controllable permeability to gate the diffusion of substrates and products across the bilayer. In the past decade, significant efforts have been made to development this kind of polymersomes [29,30,31]. That includes the use of slightly hydrophilic polymers as the hydrophobic part, inclusion of transmembrane proteins as pores [32, 33] and also the use of directional or specific transporters like proteorhodopsin or gramicidin [24, 34,35,36]. In order to control permeability in case of unspecific pores, a responsive cover can be attached to the transmembrane protein (e.g. OmpF) [37].

In order to increase the mechanical stability even further and to increase the options for membrane permeability, the possibility of cross-linking the membrane has become a viable option. Such polymeric vesicles, besides being robust and presenting high stability due to their cross-linking, present the ability to encapsulate active enzymatic species which makes them well suited as biocatalytic nanoreactors [1, 14,15,16,17,18,19, 38]. In this mini-review, we will focus on such cross-linked polymersomes with a strong focus on the chemistry of the cross-linking which is an essential feature but often considered a minor detail and mentioned only in the supporting information. We will cover the used chemistry from historical milestones up to the most outstanding current pathways in an effort to compare the methods between each other. The chemistries of cross-linking will be discussed with a focus on the reaction conditions (time and temperature) as these values are reported in most examples. How cross-linking was proven in each of these systems will be discussed as well. The specific approaches to proof cross-linking do vary greatly, and we will show the large variety of analytical tools that can be used for this purpose. Starting with UV-aided radical cross-linking, we will then go to more mild reactions including methods that do not require an external reagent or an external initiator. A method to cross-link the hydrophilic layer of the vesicles will be shown as well.

Following this overview, we will highlight the systematic design and various functionalizations which could be achieved with the photo-cross-linked pH-sensitive polymersomes reported by the group of Appelhans and Voit. This research group has combined the stability of its cross-linked polymersomes with pH responsiveness, being able to generate on-off states for enzymatic reactions by obtaining temporally controlled, cyclic and adaptive membrane responsiveness.

Historic milestones

Cross-linking has been introduced to polymersomes shortly after they were invented. Discher et al. used a PEO45-b-PB55 (long names see Table 1) block copolymer to introduce cross-linking by radical polymerization of the residual double bonds of PB (Fig. 2 top) [39, 40]. Adding potassium peroxodisulfate to the formed polymersomes allowed for a radical polymerization within the membrane after the vesicles had been formed. Cross-linking temperature or time has not been mentioned. These vesicles then retained their shape in a good solvent for the block copolymer, here chloroform, and did not dissolve or lose any of the encapsulated sucrose solution. A transfer back to water again yielded an unchanged polymersome. Transferring the cross-linked polymersome to air yielded deflated vesicles, which rehydrated completely in water. The cross-linking efficiency has been calculated to be between 30 and 75% and the authors noted that a complete cross-linking was not necessary as long as the gel point has been reached. As soon as no free polymer chain was still present, the polymersome was viewed as cross-linked [39].

Following these first efforts, the next important milestone was reached by Armes et al., who combined cross-linking with an additional functionality [41]. By using a PEO45-b-PDEA40-r-PTMSPMA40 (long names see Table 1) polymer, pH sensitivity was introduced by PDEA and PTMSPMA ensured cross-linking of the membrane (Fig. 2 bottom). The effort was remarkable since cross-linking happened in situ during vesicle formation and did not require any additional chemical or external activation. Hydrolysis of the siloxane bonds led to a cross-linked membrane, which had been branded as “self-cross-linking”. The reaction was facilitated by amines; the presence of PDEA thus self-catalysed the reaction. Although the reaction continued for more than 200 h at room temperature (RT), cross-linking was reached within a few hours. Without PDEA in the polymer, cross-linking was reached only after 1 month. Similar to the first cross-linked vesicles, efficient cross-linking was achieved after converting 30–35% of the functional groups. If a large portion of cross-linker was used, i.e. a 1:1 ratio of PDEA and PTMSPMA, the polymersomes retained their size in acidic conditions, a good solvent for the block-copolymer. Lowering the amount of cross-linker to reach a 3:1 ratio of PDEA and PTMSPMA (i.e. PEO45-b-PDEA60-r-PTMSPMA20) led to vesicles with a defined swelling in acidic media as the positive charges from the protonated PDEA repelled each other and were not held back by a dense cross-linking. Fluorescence studies then indicated a permeable membrane in the swollen state [41].

Modern cross-linking of polymersomes

Following the early works of Discher et al. [39], radical cross-liking was also used in more recent examples of cross-linked polymersomes. Kim et al. used a (PEO12)3-b-PVS33DM166 (long names see Table 1) block copolymer, which partially contained double bonds in the siloxane side chains (Fig. 3 top) [42]. After self-assembly, the resulting giant vesicles were treated with the photoinitiator for radical polymerizations 2-hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)2-methylpropiophenone (Irgacure 2959), which lead to cross-linking. The double bonds of the vinylic side groups polymerized, leading to stabilized, cross-linked vesicles (Fig. 3 top). In contrast to an initiation via peroxodisulfate, photoinitiation had the great advantage of working at room temperature and that the hydrophobic initiator could be allowed to diffuse into the membrane. Cross-linking was finished after 5 h of irradiation at RT and proven by transfer of the polymersomes to THF, where they remained stable. An increased mechanical stability was found as extrusion through a 0.2-μm filter did not alter the size of cross-linked polymersomes, while non-cross-linked ones reduced their size over the process. Similarly, cross-linked polymersomes did not lose cargo during extrusion, while their non-cross-linked counterparts did. Measuring the E-modules of the giant polymersomes revealed an increase from 18.7 mN/m to 224.1 mN/m through cross-linking, resembling a twelvefold increase.

Top: Radical cross-linking using Irgacure 2959 leads to a polymerization of vinylic side chains of the polysiloxane. Bottom: polymerization of the methacrylic side chain of the corresponding polymers. The cross-linking moieties are highlighted with boxes and examples for a complete reaction are shown.

Radical photo-cross-linking facilitated by using Irgacure 2959 was also used by Kong et al. to cross-link polymersomes from PHEA-MA (long names see Table 1) (Fig. 3 bottom) [43]. Cross-linking occurred at RT for an unreported time. Despite their naming, these vesicles were not traditional polymersomes since the polyamide backbone showed a random substitution with hydrophilic hydroxyethyl and hydrophobic octadecyl and ethyl methacrylate units. However, the polymer self-assembled into vesicles and UV-light started the cross-linking by polymerizing the methacrylate units. Again, cross-linking was shown to reduce the leakage of cargo from the vesicles. The hydroxyl group from the hydrophilic part of the polymer was then used to conjugate a fluorescent probe to the polymer in order to track them inside a mouse body. These vesicles were studied towards cancer treatment where a reduced leakage of cargo was shown to be advantageous.

Denkova et al. cross-linked polymersomes without adding any reagent, but applied harsh, yet effective gamma radiation. These polymersomes were made from a similar polymer as Discher et al. used, namely PEO21-b-PB33 but with different block lengths as compared with the original publication (structure of the repeating units in Fig. 2) [39, 44]. Gamma radiation caused the formation of radicals, which then started the cross-linking reaction within the membrane of the polymersome. The authors noted that very harsh radiation of 59 kGy over 40 h at RT was the minimal amount to reach cross-linking and also led to a decrease in the hydrodynamic diameter compared with non-cross-linked polymersomes. This is notable since cross-linking did not change the hydrodynamic diameter of polymersomes in the reports discussed so far. Cross-linking was proven by immersing the polymersomes into THF, which did not disassemble the cross-linked vesicles as it did with non-cross-linked ones. In contrast to the reports discussed so far, the polymersomes did swell in THF, so the cross-linking was not as dense as for those of Discher et al. Although this approach is arguably not feasible for any biological application, including the use of enzymes, it proved to be effective in this instance.

Cross-linking just by irradiation and without the addition of chemicals could also be achieved using UV light as a less harsh irradiation. Amsden et al. used it to cross-link cinnamoyl residues in their polymersomes made from PEO17-b-P(TMC13-r-MUM6.5) (long names see Table 1) (Fig. 4 top) [45]. Applying a wavelength of 365 nm for 10 min at RT, the cinnamoyl residues cross-linked by forming a 4-membered ring. Stability was probed by immersing the samples into a solution of 33 vol% THF followed by centrifugation. DLS then revealed that non-cross-linked polymers showed aggregation, which decreased considerably the longer the polymersomes were irradiated (5 min and 10 min of irradiation). Confocal microscopy was used to differentiate between aggregates and vesicles in the corresponding samples, since only vesicles would appear as hollow structures rather than filled circles. DLS data was backed up by fluorescence imaging which again showed the aforementioned aggregation as well as retention of polymersomes after irradiation. While an increased stability was proven, it remained unclear whether 10 min of irradiation was enough to achieve complete cross-linking of the polymersomes.

Hickey et al. also used a UV-initiated approach, but had to add an external cross-linker to their membranes from PEO-b-PI and PI-b-PEO-b-PI (long names see Table 1) (Fig. 4 bottom) [46]. Although the block length was not defined, the volume fraction of PEO was determined to be 0.46 for the AB as well as for the ABA block-copolymer. 4 mol% of pentaerythritol tetra(3-mercaptopropionate) was used as cross-linking agent. The thiol units cross-linked the polymer by reacting with the residual double bonds of PI while being irradiated with UV light of 365 nm (Fig. 4). After 45 min of cross-linking time at RT, no further reaction of the double bonds was detected by FTIR, showing that the maximum cross-linking was reached. Stability of the final membrane was not investigated further. Chen et al. also applied thiol-based cross-linking recently. Thiol-containing polymers formed disulphide bonds during self-assembly and cross-linked the newly formed structures [47].

Armes et al. produced cross-linkable vesicles from PGMA55-b-P(HPMA247-r-GlyMA82) (long names see Table 1) from polymerization-induced self-assembly (PISA) (Fig. 5) [48]. Using bifunctional amines, these vesicles were then cross-linked through a ring-opening reaction of the epoxide. Together with a work from O’Reilly et al. [49] on PEO113-b-P(HPMA320-r-GlyMA80), a large variety of cross-linkers were used, ranging from bifunctional PEO, PPO (i.e. “Jeffamine”) to small aliphatic amines like ethylenediamine, butyldiamine or similar (Fig. 5). Cross-linking with these bifunctional molecules was reached at 20 °C overnight (app. 18 h) and held an interesting twist, as adding them to vesicles with no epoxide functionality caused disassembly of the vesicles. Since bifunctional amines are surfactants, this is no surprise but showed that the cross-linking reaction was faster than the surfactant-induced disassembly process. Cross-linking was then proven as no disassembly occurred upon adding surfactants. O’Reilly et al. discovered that small-molecule amines cause a vesicle to shrink in diameter (180 to 125 nm) while bifunctional PEO amines caused a swelling of the membrane and result in diameters of about 240 nm (also from 180 nm). The authors reasoned the shrinking with a more compact membrane in case of short cross-linkers. In contrast, the swelling was reasoned with the space required of the (hydrated) PEO chains as cross-linkers and the generally increased hydration of the more hydrophilic membrane due to the hydrophilic cross-linker. Both findings were especially remarkable as the works discussed so far showed no or limited differences in diameter before and after cross-linking.

A combination of two cross-linking approaches was used by Yoshida et al. to stabilize their polymersomes [50]. In a PEO113-b-P(NIPAAm540-r-NAPMAm15-r-NAPMAmRu(bpy)13-r-NAPMAmMA7) (long names see Table 1) system, a photopolymerization of the methacrylic units formed irreversible cross-linking bonds within the polymersome membrane (Fig. 6 top). Irradiating the sample for 15 min at 30 °C with the photo-initiator 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride yielded cross-linked polymersomes. In addition, the ruthenium complex acted as cross-linker through intermolecular ligand exchange, which eventually interconnected two polymer chains. However, the Ru complex mainly acted as redox-responsive unit to create “beating” polymersomes [50]. Since the polymeric system was also temperature-sensitive, stability could be shown exploiting that fact. Without cross-links, the polymersomes dissolved into unimers at 18 °C and did form polymersomes at 25 °C only. After cross-linking, the polymersomes were present at both temperatures, but were of a larger diameter at lower temperatures due to the hydration of the polymer.

All cross-linking efforts discussed so far have been achieved in the hydrophobic part of the membrane enclosing the polymersome. Zhu et al. chose a different approach with vesicles from PEO113-b-PCL215, (long names see Table 1) which were cross-linked in the PEO domain by introducing Mo154 polyoxometalates (POM) (Fig. 6 bottom) [51]. After adding the metal complex, the polymersomes were incubated at RT for 15 min. POM is negatively charged and induced a shrinkage of the polymersomes, which was measured by DLS. This implied not only a shrinking of the PEO corona but also a dissociation of polymersome aggregates due to electrostatic repulsion. Stability of the complex-stabilized polymersomes was proven by AFM as they were now able to withstand the mechanically rather disturbing contact mode and even after air-purging and drying. A spherical shape was maintained throughout while polymersomes without the metal complex disintegrated under these harsh conditions.

Photo-cross-linked and pH-sensitive polymersomes

Until now, we have focused on the cross-linking chemistries employed. Cross-linked vesicles bearing responsive membranes to different stimuli have led to interesting and promising works in recent years [42, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. One of the cross-linked polymersomes, which have been studied very intensively over the last 10 years, are the photo-cross-linked and pH sensitive ones from Voit et al. first reported in 2011 [59]. We will now focus on this polymer and the application of the corresponding polymersomes as functional nanoreactors as single compartment and novel contribution in the field of multicompartments [9, 17, 60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

The underlying “standard” block copolymer (BCP) was synthesized by atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) [68]; it had methoxy end groups at the hydrophilic poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) segment, while the hydrophobic part consisted of the polymerized pH-sensitive DEA like Armes et al. used and the photo-cross-linker, 3,4-dimethyl maleic imidobutyl methacrylate (DMIBMA). A typical composition was PEO45-b-PDEA80-r-PDMIMBA20. Polymersomes were typically fabricated by the self-assembly of BCPs, using the so-called pH switch method (Fig. 7A) [69]. Cross-linking was performed with UV light at pH ≥ 8 with the deprotonated PDEA at RT between 90 and 180 s, a time that ensured that the vesicles were thoroughly cross-linked. Thanks to the cross-linking, these vesicles now showed a pH-dependent swelling and deswelling. Upon protonation of PDEA, the vesicles exhibited a defined swelling and returned back to their original size upon deprotonation. A stable swelling-deswelling behaviour over at least 5 cycles was reported as a proof of thorough cross-linking. These polymersomes have the advantage of being mechanically tough and small (between 90 and 150 nm) which made them excellent candidates for application in biomedicine as nanocarriers [61, 70]. Similar pH-sensitive block copolymers were prepared using a commercial cross-linker (2-hydroxy-4-(methacryloyloxy) benzophenone, BMA) facilitating the synthesis of precursors and introducing various end groups (N3, NH2, adamantane groups) [9, 65, 66]. These end groups allowed further functionalization using different approaches such as click chemistry or host-guest interactions and were used to obtain multifunctionalized polymersomes by pH switch and subsequent photo-cross-linking [9, 65, 66]. It is important to mention that BMA facilitated the polymer synthesis, but it was more sensitive to light, i.e. showed slow self-cross-linking, and the cross-linking times were longer (around 30-min irradiation).

(A) Chemical structure of the “standard” block copolymer (BCP); (B) DLS titration curves of the assembled vesicles are shown accompanied by the determination of the critical pH value (pH*) by fitting of the DLS data; (C) General protocol for preparation in situ enzyme-containing polymersomes; (D) Scheme of sequential enzymatic reaction; (E) Reconstitution of enzyme-containing polymersomes using SM-1 (− 20 °C) and SM2 (lyophilization in presence of inulin)

Photo-cross-linked and pH-sensitive polymersomes provided a basis for pH-controlled enzymatic reactions with no transmembrane protein needed for transmembrane diffusion [17]. This is a key advantage of such polymersomes [71, 72]. In other systems, significant efforts were required to solve this problem, including the creation of vesicle-templated porous nanocapsules with a precise control of pore size and selective permeability [29,30,31], or the incorporation of bio(macro)molecules (enzymes, proteins, protein complexes, nanoparticles, etc.) into the membranes [73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. For the pH-sensitive photo-cross-liked polymersomes, control was exerted using a switch between an off (pH 8, deswollen) and on (pH 6, swollen) state. Only the on state allowed for diffusion across the membrane to reach an encapsulated enzyme within the polymersomes (Fig. 7C). Examples included a single type of enzyme and different enzymes in one polymersome or in two different polymersomes. This pH-tunable gate was used to investigate their use in sequential enzymatic reactions (glucose oxidase, myoglobin and horseradish peroxidase). Transmembrane diffusion and overcoming the space distance between polymersomes were shown successfully, meaning that educts and products were exchanged between enzyme-hosting polymersomes for successful enzymatic cascade reactions (Fig. 7D) [17]. Besides their ability to regulate enzymatic reactivity, the polymersomes showed also a considerable stabilization effect on enzymes. A free enzyme in solution rapidly lost its catalytic activity, while polymersome-encapsulated enzymes retained their ability to catalyse reactions at the same level for at least 10 days. The exact reason for this behaviour was not investigated further.

To expand the biomedical applications of these pH-responsive polymersomes, it was necessary to adjust the pH and solution conditions (salt concentration etc.) to obtain a semi-swollen or fully swollen state depending on the desired application. Therefore, adjusting the pH* (pH-triggered transition of the membrane permeability/turning point) parameter was studied in-depth (Fig. 7B) [64]. Fine-tuning the shift of the pH* of the standard photo-cross-linked polymersomes in the pH range of 5.1 and 6.8 was established by adjusting the composition of the hydrophobic block. The pH-responsiveness of these polymersomes was associated with the protonation of the tertiary amino groups of the DEAEMA units. Shifting the critical pH response value of the standard polymersomes (Fig. 7B, pH 6.6) towards more acidic conditions was achieved by replacing the pH-responsive monomer DEAEMA successively by non-responsive n-butyl methacrylate (nBMA). Using PEO45-b-PDEA46-r-PDMIBMA23-r-PBMA38, a pH* of 5.1 could be reached in 1 mM NaCl. On the another hand, to move the pH-induced swelling towards neutral pH, the responsive DEAEMA monomer (pKB 5.2) was partly substituted by its dimethylamino analogue (DMAEMA), which possessed a slightly larger pKB of 5.7. A shift to 6.8 was reached with PEO45-b-PDEA42-r-PDMIBMA25-r-PDMAEMA36 in 10 mM NaCl. Besides the interplay of composition of BCPs for tuning pH*, the salt concentration (mainly the NaCl) was identified as an important key parameter to influence pH*. It rose with increasing salt concentration from 6.5 for 1 mM NaCl for the standard BCP to 7.2 for 150 mM NaCl [64].

In the biomedical field, it is important to design polymeric vesicles with versatile and adequate properties, but moreover, it is crucial to fabricate biologically active materials of desirable quality that retain their physico-chemical characteristics after a long time under adequate storage conditions [9, 17, 60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. The cross-linked vesicles have been shown to be very good in this respect due to the demonstrated reconstitution of biologically active polymersomes from the frozen or solid state. Plain polymersomes, surface-functionalized (HSA) ones and enzyme-containing ones (Myo), were cryogenically frozen (− 20 °C) or freeze-dried in presence of a lyoprotectant (inulin (0.1% w/v)) and stored for a defined time period up to 1 month (Fig. 7E). Reconstituting those polymersomes in solution by thawing or redispersing revealed that they retained their original physical properties (diameter, membrane thickness and cyclic pH-switches) as well as their function as a pH-switchable enzymatic nanoreactor [9, 17, 60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. This study has allowed for easy handling, reproducibility and storage of polymersomes between experiments and safe transport making them suitable for external collaborations.

These pH-responsive polymersomes could be suitable as mimics of cell compartments. Understanding the parameters which define the crossing of the polymersome membrane is an important prerequisite on this pathway. Several nanoparticles (gold, glycopolymer protein mimics, and the enzymes myoglobin and esterase) were investigated in situ and post-loading processes. In this case, we focused on the extraction information about the loading efficiency and potential locations of the cargo (enzymes) using asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation (AF4) as a sophisticated analytical tool with multiple detectors [63]. Enzymes such as myoglobin and esterase were studied, and empty polymersomes were used as a reference. Myoglobin was a small protein with number average molar mass of 16 kg mol−1 and 5 nm in diameter, while esterase was characterized by 185 kg mol−1 and 10 nm in diameter (Fig. 8). The slope of the scaling plot corresponded to the exponent ν in the scaling law Rg = K·Mν (Rg = radius of gyration, K = cross-section, M = molar mass and ν = scaling parameter) and enabled the interpretation of shape and conformation of the particles. A high slope indicated a more stiff and rod-like conformation. A low slope (close to 0.33), on the other hand, indicated a compact (spherical) conformation. Studying the conformation of the membrane of the polymersomes after enzyme loading showed a clear dependency on the type of loaded protein and used encapsulation method (Fig. 8).

Left: Schematic representation of the in situ loading and post-loading strategy and simplified visualization of possible locations of encapsulated cargo within the vesicle membrane. Right: Study on main location of enzyme-loaded Psome using the scaling parameters determined by AF4 [63]

According to the loading efficiency, the post-loading of myoglobin was more effective than in situ strategy. Loading esterase, however, showed the opposite behaviour, since in situ loading proved more effective. This difference could be attributed to role of the size, since the smaller enzyme myoglobin could cross the membrane to the lumen in the swollen state. Deeper analysis of the vesicle’s conformation (Rg and ν parameter were more influenced) revealed that substantial amounts of esterase were incorporated into the hydrophobic membrane if post-loading was used (Fig. 8, location 2). In the case of post-loading of esterase, Rg and ν were similar to empty polymersomes, which suggested light interaction with the surface, which would mean location 1 (on the membrane). In case of myoglobin, the opposite behaviour was observed; the structural parameters were more influenced using post-loading. It allowed to postulate that the enzyme was mainly in the lumen or on the surface (location 1 or 4), or that the incorporation in the membrane (location 2) did not influence the properties of the membrane [63]. It is important to highlight that this study has established AF4 as a powerful characterization method which allowed determining key parameters of the loaded nanoreactors, which will be useful for the design of the next generation of enzyme-loaded polymersomes.

Transmembrane diffusion was probed using selective complexation via the cyclodextrine-adamantane interaction since it was a key parameter. Cross-linked pH-sensitive polymersomes decorated with adamantane groups were fabricated and used for non-covalent docking processes with cyclodextrin-modified molecules (small molecules as well as a nanometre-sized-modified glycodendrimer (∅ ≈ 6 nm)). Host-guest interactions between adamantane (belong to the polymersomes) and cyclodextrin groups as well as non-covalent interactions between PEO tails and cyclodextrin group were used to achieve selective and dynamic functionalization of both the inner and outer leaflet of the polymersome membrane (Fig. 9) [66]. For that, the following steps were studied: (1) a selective outer complexation using the cyclodextrine-adamantane complex during a collapsed state (non-permeable membrane); (2) displacement of the previous cyclodextrine-adamantane complex using excess of cyclodextrin showing a dynamic functionalization; (3) an inner and outer complexation using the cyclodextrine-adamantane complex during swollen state (permeable membrane) using one kind of cyclodextrin-modified molecule, this step showed the potential transmembrane diffusion using biomolecules with different sizes; (4) outer displacement using another kind of cyclodextrin-modified molecule during the collapsed state (non-permeable membrane) obtaining the desired dual functionalization. This study gave insights on how to control the selective functionalization of both surfaces of the polymersome membrane, and on the post-encapsulation of nanometre-sized biological entities into the cavities of the polymersomes [66]. Also, post-encapsulation of cargo, i.e. loading without changing the morphology of these polymersomes, was exemplified and proved to be a valuable tool for the implementation of cell-like functions within polymersomes.

Studied sequential docking and undocking processes at the inner and outer spheres of polymersomes’ membrane using host-guest interactions. Block copolymers BC1 (90%, MeO end group) and BC2 (10%, adamantane end group) used for polymersome formation and characterization of polymersomes. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons [66]

While these vesicles have been mainly used as nanoreactors, their functionalization for use in drug delivery was also reported. Polymersomes decorated with adamantane and azide groups were prepared by mixed self-assembly of suitably end-modified block copolymers. A subsequent post-modification of the polymersome surface was achieved using covalent (azide-alkyne click reaction, similar to Fig. 9) and non-covalent approaches (adamantane-β-cyclodextrin host-guest complex). All reactive groups showed sufficient accessibility as well as selective and orthogonal reactivity. Moreover, doxorubicin-loaded multifunctional polymersomes were prepared for an efficient pH-controlled drug release [65]. Using this methodology, functionalized polymersomes with folate targeting antennae have also been reported [9].Thus, these pH-responsive polymersomes could effectively prohibit the premature release of chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin in physiological conditions. However, they promoted drug release once they are triggered (i.e. swollen) in the acidified endosomal compartment. The membrane served as a gate which undergoes “on” and “off” cycles in response to pH stimuli [9].

Compartmentalization is a fundamental requirement for many biochemical processes and also targeted using this kind of polymersomes. Multicompartmentalization in eukaryotic cells allows the positional assembly and spatial separation of biomolecules and processes in different compartments inside the cell, which provides the cell with spatiotemporal control over metabolic reactions [81, 82]. This exquisite level of organization has been an inspiration to develop novel vesicle-within-vesicle systems that are capable of mimicking cell functions as catalysis, transport, communication, interaction, self-replication or even autonomous movement [12, 26, 82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. Recently, a step further was taken by designing a highly effective route for constructing structural and functional eukaryotic cell mimics. As a first step, assembly of the enzyme-loaded (using Myo and GOx), pH-responsive and photo-cross-linked adamantyl-modified polymersomes (Ø 100 nm) was carried out. It was proven that the enzyme-loaded polymersomes could be used as pH-switchable organelle mimics (Fig. 10). A layer-by-layer assembly of [PAH/PMA(β-CD)]1/[AdaPsome/PMA(β-CD)]1/[PAH/PNMD)]3/[PAH/PMA (PEG)]1 multilayers was then conducted on spherical silica particles, followed by dissolving the silica core forming pH- and temperature-responsive and PEG-functionalized capsules (Ø 1.1–1.3 μm) (long names see Table 1). After a complex synthesis and characterization route, an excellent synthetic multicompartmentalized system was eventually obtained. These pH-sensitive polymeric vesicles were used as free-floating organelle mimics into a biomimetic cell membrane (Fig. 10). This biomimetic approach could be used in fields such as biomedicine, biocatalysis and systems biology [80].

Cell mimics equipped with pH-switchable organelle mimics and temperature- and pH-responsive biomimetic cell membrane with PEG surface functionalization. Enzymatic cascade reactions using glucose oxidase (GOx), myoglobin (Myo) and catalase (Cat) for metabolism mimicry. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons [80]

Conclusions

It is evident that scientists have used a broad range of available chemistries to achieve cross-linked polymersomes. Radical cross-linking, UV-based thiol-ene reactions, photochemical reactions and even the use of metal complexes have been depicted here. All of these efforts have increased the mechanical stability of polymersomes compared with their respective non-cross-linked analogues. The cross-linking reaction avoided the disassembly of the polymersomes, but unfolded even greater potential when it was successfully combined with pH sensitivity. Using pH as trigger, the photo-cross-linked polymersomes from the Voit and Appelhans group have multiple applications as nanoreactors. Substrates for the enclosed enzymes reached the vesicles in an acidic (swollen) state but not in their native collapsed state. Several studies have clarified the location of the enzymes and the pH control of the permeability of the membrane. It was even possible to fine-tune the pH* value of such polymersomes. Moreover, a sophisticated multicompartment system as a functional cell-mimicking system has been designed. Due to their advanced stability, robustness, easy handing and multiple possible uses, we are certain that these systems will develop further and continue to play an important role in modern research on biomimetic systems.

References

Gaitzsch J, Huang X, Voit B (2016) Engineering functional polymer capsules toward smart nanoreactors. Chem Rev 116(3):1053–1093

Leong J, Teo JY, Aakalu VK, Yang YY, Kong H (2018) Engineering polymersomes for diagnostics and therapy. Adv Health Mater 7(8):1701276

Chimisso V, Maffeis V, Hürlimann D, Palivan CG, Meier W (2020) Self-assembled polymeric membranes and Nanoassemblies on surfaces: preparation, characterization, and current applications. Macromol Biosci 20(1):1900257

Canton I, Battaglia G (2012) Endocytosis at the nanoscale. Chem Soc Rev 41(7):2718–2739

Pachioni-Vasconcelos JD, Lopes AM, Apolinario AC, Valenzuela-Oses JK, Costa JSR, Nascimento LD, Pessoa A, Barbosa LRS, Rangel-Yagui CD (2016) Nanostructures for protein drug delivery. Biomater Sci 4(2):205–218

Einfalt T, Goers R, Gaitzsch J, Gunkel-Grabole G, Schoenenberger CA, Palivan C (2016) Vesikel aus Polymeren. Nachrichten aus der Chemie 64(10):965–967

Discher DE, Discher BM, Won YY, Ege DS, Lee JCM, Bates FS, Hammer DA (1999) Polymersomes: tough vesicles made from diblock copolymers. Science 284(5417):1143–1146

Messager L, Gaitzsch J, Chierico L, Battaglia G (2014) Novel aspects of encapsulation and delivery using polymersomes. Curr Opin Pharmacol 18:104–111

Yassin MA, Appelhans D, Wiedemuth R, Formanek P, Boye S, Lederer A, Temme A, Voit B (2015) Overcoming concealment effects of targeting moieties in the PEG Corona: controlled permeable polymersomes decorated with Folate-antennae for selective targeting of tumor cells. Small 11(13):1580–1591

Weijing Y, Yifeng X, Yuan F, Fenghua M, Jian Z, Ru C, Chao D, Zhiyuan Z (2018) Selective cell penetrating peptide-functionalized polymersomes mediate efficient and targeted delivery of methotrexate disodium to human lung cancer in vivo. Adv Health Mater 7(7):1701135

Yang W, Wei Y, Yang L, Zhang J, Zhong Z, Storm G, Meng F (2018) Granzyme B-loaded, cell-selective penetrating and reduction-responsive polymersomes effectively inhibit progression of orthotopic human lung tumor in vivo. J Control Release 290:141–149

Fernandez-Trillo F, Grover LM, Stephenson-Brown A, Harrison P, Mendes PM (2017) Vesicles in nature and the laboratory: elucidation of their biological properties and synthesis of increasingly complex synthetic vesicles. Angew Chem Inter Ed 56(12):3142–3160

Tanner P, Balasubramanian V, Palivan CG (2013) Aiding nature’s organelles: artificial peroxisomes play their role. Nano Lett 13(6):2875–2883

Che H, Cao S, van Hest JCM (2018) Feedback-induced temporal control of “breathing” polymersomes to create self-adaptive nanoreactors. J Am Chem Soc 140(16):5356–5359

Che H, van Hest JCM (2016) Stimuli-responsive polymersomes and nanoreactors. J Mater Chem B 4(27):4632–4647

Feng A, Yuan J (2014) Smart nanocontainers: progress on novel stimuli-responsive polymer vesicles. Macromol Rapid Commun 35(8):767–779

Grafe D, Gaitzsch J, Appelhans D, Voit B (2014) Cross-linked polymersomes as nanoreactors for controlled and stabilized single and cascade enzymatic reactions. Nanoscale 6(18):10752–10761

Louzao I, van Hest JCM (2013) Permeability effects on the efficiency of antioxidant nanoreactors. Biomacromolecules 14(7):2364–2372

Peters RJRW, Marguet M, Marais S, Fraaije MW, van Hest JCM, Lecommandoux S (2014) Cascade reactions in multicompartmentalized polymersomes. Angew Chemie Inter Ed 53(1):146–150

Che H, van Hest JCM (2019) Adaptive polymersome nanoreactors. ChemNanoMat 5(9):1092–1109

Chen X, Ding X, Zheng Z, Peng Y (2006) Thermosensitive cross-linked polymer vesicles for controlled release system. New J Chem 30(4):577–582

de Vries WC, Kudruk S, Grill D, Niehues M, Matos ALL, Wissing M, Studer A (2019) Controlled cellular delivery of amphiphilic cargo by redox-responsive Nanocontainers. Adv Sci 6(24):1901935

Palivan CG, Goers R, Najer A, Zhang X, Car A, Meier W (2016) Bioinspired polymer vesicles and membranes for biological and medical applications. Chem Soc Rev 45(2):377–411

Lomora M, Garni M, Itel F, Tanner P, Spulber M, Palivan CG (2015) Polymersomes with engineered ion selective permeability as stimuli-responsive nanocompartments with preserved architecture. Biomaterials 53:406–414

Yan Y, Wang Y, Heath JK, Nice EC, Caruso F (2011) Cellular association and cargo release of redox-responsive polymer capsules mediated by exofacial thiols. Adv Mater 23(34):3916–3921

Abdelmohsen LK, Nijemeisland M, Pawar GM, Janssen GJ, Nolte RJ, van Hest JC, Wilson DA (2016) Dynamic loading and unloading of proteins in polymeric Stomatocytes: formation of an enzyme-loaded supramolecular nanomotor. ACS Nano 10(2):2652–2660

Sun J, Mathesh M, Li W, Wilson DA (2019) Enzyme-powered nanomotors with controlled size for biomedical applications. ACS Nano 13(9):10191–10200

Joseph A, Contini C, Cecchin D, Nyberg S, Ruiz-Perez L, Gaitzsch J, Fullstone G, Tian X, Azizi J, Preston J, Volpe G, Battaglia G (2017) Chemotactic synthetic vesicles: design and applications in blood-brain barrier crossing. Sci Adv 3(8):e1700362

Dergunov SA, Kim MD, Shmakov SN, Pinkhassik E (2018) Building functional Nanodevices with vesicle-templated porous polymer nanocapsules. Acc Chem Res 52(1):189–198

Kim KT, Cornelissen JJLM, Nolte RJM, Hest JCMv (2009) A polymersome nanoreactor with controllable permeability induced by stimuli-responsive block copolymers. Adv Mater 21(27):2787–2791

Spulber M, Najer A, Winkelbach K, Glaied O, Waser M, Pieles U, Meier W, Bruns N (2013) Photoreaction of a hydroxyalkyphenone with the membrane of polymersomes: a versatile method to generate semipermeable nanoreactors. J Am Chem Soc 135(24):9204–9212

Kumar M, Grzelakowski M, Zilles J, Clark M, Meier W (2007) Highly permeable polymeric membranes based on the incorporation of the functional water channel protein aquaporin Z. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104(52):20719–20724

Belluati A, Mikhalevich V, Yorulmaz Avsar S, Daubian D, Craciun I, Chami M, Meier W, Palivan CG (2020) How do the properties of Amphiphilic polymer membranes influence the functional insertion of peptide pores? Biomacromolecules 21(2):701–715

Goers R, Thoma J, Ritzmann N, Di Silvestro A, Alter C, Gunkel-Grabole G, Fotiadis D, Müller DJ, Meier W (2018) Optimized reconstitution of membrane proteins into synthetic membranes. Commun Chem 1(1):35

Gaitzsch J, Hirschi S, Freimann S, Fotiadis D, Meier W (2019) Directed insertion of light-activated proteorhodopsin into asymmetric polymersomes from an ABC block copolymer. Nano Lett 19(4):2503–2508

Konishcheva E, Daubian D, Gaitzsch J, Meier W (2018) Synthesis of linear ABC triblock copolymers and their self-assembly in solution. Helv Chim Acta 101(2):e1700287

Edlinger C, Einfalt T, Spulber M, Car A, Meier W, Palivan CG (2017) Biomimetic strategy to reversibly trigger functionality of catalytic nanocompartments by the insertion of pH-responsive biovalves. Nano Lett 17(9):5790–5798

Marguet M, Bonduelle C, Lecommandoux S (2013) Multicompartmentalized polymeric systems: towards biomimetic cellular structure and function. Chem Soc Rev 42(2):512–529

Discher DE, Discher BM, Bermudez H, Hammer DA, Won YY, Bates FS (2002) Cross-linked polymersome membranes: vesicles with broadly adjustable properties. J Phys Chem B 106(11):2848–2854

Won YY, Davis HT, Bates FS (1999) Giant wormlike rubber micelles. Science 283(5404):960–963

Du J, Armes SP (2005) pH-responsive vesicles based on a hydrolytically self-cross-linkable copolymer. J Am Chem Soc 127(37):12800–12801

Kim J, Jeong S, Korneev R, Shin K, Kim KT (2019) Cross-linked polymersomes with reversible deformability and oxygen transportability. Biomacromolecules 20(6):2430–2439

Lai MH, Lee S, Smith CE, Kim K, Kong H (2014) Tailoring polymersome bilayer permeability improves enhanced permeability and retention effect for bioimaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 6(13):10821–10829

Wang G, Hoornweg A, Wolterbeek HT, Franken LE, Mendes E, Denkova AG (2015) Enhanced retention of encapsulated ions in cross-linked polymersomes. J Phys Chem B 119(11):4300–4308

Chesterman JP, Chen F, Brissenden AJ, Amsden BG (2017) Synthesis of cinnamoyl and coumarin functionalized aliphatic polycarbonates. Polym Chem 8(48):7515–7528

Lang C, Shen YX, LaNasa JA, Ye D, Song W, Zimudzi TJ, Hickner MA, Gomez ED, Gomez E, Kumar M et al (2018) Creating cross-linked lamellar block copolymer supporting layers for biomimetic membranes. Faraday Discuss 209:179–191

Yang WJ, Zhu GZ, Wang S, Yu GC, Yang Z, Lin LS, Zhou ZJ, Liu YJ, Dai YL, Zhang FW, Shen Z, Liu Y, He Z, Lau J, Niu G, Kiesewetter DO, Hu S, Chen X (2019) In situ dendritic cell vaccine for effective cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano 13(3):3083–3094

Chambon P, Blanazs A, Battaglia G, Armest SP (2012) How does cross-linking affect the stability of block copolymer vesicles in the presence of surfactant? Langmuir 28(2):1196–1205

Varlas S, Foster JC, Georgiou PG, Keogh R, Husband JT, Williams DS, O'Reilly RK (2019) Tuning the membrane permeability of polymersome nanoreactors developed by aqueous emulsion polymerization-induced self-assembly. Nanoscale 11(26):12643–12654

Tamate R, Ueki T, Yoshida R (2015) Self-Beating Artificial Cells: Design of cross-linked polymersomes showing self-oscillating motion. Adv Mater 27(5):837–842

Jing B, Wang X, Wang H, Qiu J, Shi Y, Gao H, Zhu Y (2017) Shape and mechanical control of poly(ethylene oxide) based polymersome with polyoxometalates via hydrogen bond. J Phys Chem B 121(7):1723–1730

Liu X, Yaszemski MJ, Lu L (2016) Expansile crosslinked polymersomes for pH sensitive delivery of doxorubicin. Biomater Sci 4(2):245–249

Mai BT, Barthel M, Marotta R, Pellegrino T (2019) Crosslinked pH-responsive polymersome via Diels-Alder click chemistry: a reversible pH-dependent vesicular nanosystem. Polymer 165:19–27

Deng Z, Qian Y, Yu Y, Liu G, Hu J, Zhang G, Liu S (2016) Engineering intracellular delivery nanocarriers and nanoreactors from oxidation-responsive polymersomes via synchronized bilayer cross-linking and permeabilizing inside live cells. J Am Chem Soc 138(33):10452–10466

Xu H, Meng F, Zhong Z (2009) Reversibly crosslinked temperature-responsive nano-sized polymersomes: synthesis and triggered drug release. J Mater Chem 19(24):4183–4190

Kim BS, Chuanoi S, Suma T, Anraku Y, Hayashi K, Naito M, Kim HJ, Kwon IC, Miyata K, Kishimura A, Kataoka K (2019) Self-assembly of siRNA/PEG-b-catiomer at integer molar ratio into 100 nm-sized vesicular polyion complexes (siRNAsomes) for RNAi and codelivery of cargo macromolecules. J Am Chem Soc 141(8):3699–3709

Sun H, Meng F, Cheng R, Deng C, Zhong Z (2014) Reduction and pH dual-bioresponsive crosslinked polymersomes for efficient intracellular delivery of proteins and potent induction of cancer cell apoptosis. Acta Biomater 10(5):2159–2168

Ke W, Li J, Mohammed F, Wang Y, Tou K, Liu X, Wen P, Kinoh H, Anraku Y, Chen H, Kataoka K, Ge Z (2019) Therapeutic polymersome nanoreactors with tumor-specific activable cascade reactions for cooperative cancer therapy. ACS Nano 13(2):2357–2369

Gaitzsch J, Appelhans D, Grafe D, Schwille P, Voit B (2011) Photo-crosslinked and pH sensitive polymersomes for triggering the loading and release of cargo. Chem Commun 47(12):3466–3468

Ccorahua R, Moreno S, Gumz H, Sahre K, Voit B, Appelhans D (2018) Reconstitution properties of biologically active polymersomes after cryogenic freezing and a freeze-drying process. RSC Adv 8(45):25436–25443

Gaitzsch J, Appelhans D, Wang L, Battaglia G, Voit B (2012) Synthetic bio-nanoreactor: mechanical and chemical control of polymersome membrane permeability. Angew Chem Inter Ed 51(18):4448–4451

Gaitzsch J, Canton I, Appelhans D, Battaglia G, Voit B (2012) Cellular interactions with photo-cross-linked and pH-sensitive polymersomes: biocompatibility and uptake studies. Biomacromolecules 13(12):4188–4195

Gumz H, Boye S, Iyisan B, Krönert V, Formanek P, Voit B, Lederer A, Appelhans D (2019) Toward functional synthetic cells: in-depth study of nanoparticle and enzyme diffusion through a cross-linked polymersome membrane. Adv Sci 6(7):1801299

Gumz H, Lai TH, Voit B, Appelhans D (2017) Fine-tuning the pH response of polymersomes for mimicking and controlling the cell membrane functionality. Polym Chem 8(19):2904–2908

Iyisan B, Kluge Jr, Formanek P, Voit B, Appelhans D (2016) Multifunctional and dual-responsive polymersomes as robust nanocontainers: design, formation by sequential post-conjugations, and pH-controlled drug release. Chem Mater 28(5):1513–1525

Iyisan B, Siedel AC, Gumz H, Yassin M, Kluge J, Gaitzsch J, Formanek P, Moreno S, Voit B, Appelhans D (2017) Dynamic docking and undocking processes addressing selectively the outside and inside of polymersomes. Macro Rapid Commun 38(21):1700486-n/a

Liu X, Appelhans D, Wei Q, Voit B (2017) Photo-cross-linked dual-responsive hollow capsules mimicking cell membrane for controllable cargo post-encapsulation and release. Adv Sci 4(3):1600308

Matyjaszewski K (2012) Atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP): current status and future perspectives. Macromolecules 45(10):4015–4039

Pearson RT, Warren NJ, Lewis AL, Armes SP, Battaglia G (2013) Effect of pH and temperature on PMPC–PDPA copolymer self-assembly. Macromolecules 46(4):1400–1407

Gaitzsch J, Appelhans D, Janke A, Strempel M, Schwille P, Voit B (2014) Cross-linked and pH sensitive supported polymer bilayers from polymersomes – studies concerning thickness, rigidity and fluidity. Soft Matter 10(1):75–82

Battaglia G, Ryan AJ, Tomas S (2006) Polymeric vesicle permeability: a facile chemical assay. Langmuir 22(11):4910–4913

Lomora M, Dinu IA, Itel F, Rigo S, Spulber M, Palivan CG (2015) Does membrane thickness affect the transport of selective ions mediated by Ionophores in synthetic membranes? Macro Rapid Commun 36(21):1929–1934

Palivan CG, Fischer-Onaca O, Delcea M, Itel F, Meier W (2012) Protein-polymer nanoreactors for medical applications. Chem Soc Rev 41(7):2800–2823

Konishcheva EV, Daubian D, Rigo S, Meier WP (2019) Probing membrane asymmetry of ABC polymersomes. Chem Commun 55:1148–1151

Nallani M, Andreasson-Ochsner M, Tan CW, Sinner EK, Wisantoso Y, Geifman-Shochat S, Hunziker W (2011) Proteopolymersomes: in vitro production of a membrane protein in polymersome membranes. Biointerphases 6(4):153–157

Sanborn JR, Chen X, Yao Y-C, Hammons JA, Tunuguntla RH, Zhang Y, Newcomb CC, Soltis JA, De Yoreo JJ, Van Buuren A et al (2018) Carbon nanotube porins in amphiphilic block copolymers as fully synthetic mimics of biological membranes. Adv Mater 30(51):1803355

Itel F, Najer A, Palivan CG, Meier W (2015) Dynamics of membrane proteins within synthetic polymer membranes with large hydrophobic mismatch. Nano Lett 15(6):3871–3878

Bruns N, Lörcher S, Makyła-Juzak K, Pollarda J, Renggli K, Spulber M (2013) Combining polymers with the functionality of proteins: new concepts for atom transfer radical polymerization, nanoreactors and damage self-reporting materials. Chimia 67:777–781

Kauscher U, Holme MN, Björnmalm M, Stevens MM (2019) Physical stimuli-responsive vesicles in drug delivery: beyond liposomes and polymersomes. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 138:259–275

Liu X, Formanek P, Voit B, Appelhans D (2017) Functional cellular mimics for the spatiotemporal control of multiple enzymatic cascade reactions. Angew Chem 129(51):16451–16456

Schoonen L, van Hest JC (2016) Compartmentalization approaches in soft matter science: from nanoreactor development to organelle mimics. Adv Mater 28(6):1109–1128

Tu Y, Peng F, Adawy A, Men Y, Abdelmohsen LKEA, Wilson DA (2016) Mimicking the cell: bio-inspired functions of supramolecular assemblies. Chem Rev 116(4):2023–2078

Booth R, Qiao Y, Li M (2019) Spatial positioning and chemical coupling in coacervate-in-proteinosome protocells. Angew Chem Int Ed 58(27):9120–9124

Huang X, Li M, Mann S (2014) Membrane-mediated cascade reactions by enzyme-polymer proteinosomes. Chem Commun 50(47):6278–6280

Liu X, Zhou P, Huang Y, Li M, Huang X, Mann S (2016) Hierarchical proteinosomes for programmed release of multiple components. Angew Chem Int Ed 55(25):7095–7100

Wang T, Xu J, Fan X, Yan X (2019) Giant “breathing” proteinosomes with jellyfish-like property. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 11(50):47619–47624

Huang X, Li M, Green DC, Williams DS, Patil AJ, Mann S (2013) Interfacial assembly of protein-polymer nano-conjugates into stimulus-responsive biomimetic protocells. Nat Commun 4:2239

Gobbo P, Patil AJ, Li M, Harniman R, Briscoe WH, Mann S (2018) Programmed assembly of synthetic protocells into thermoresponsive prototissues. Nat Mater 17(12):1145–1153

Garni M, Einfalt T, Goers R, Palivan CG (2018) Live follow-up of enzymatic reactions inside the cavities of synthetic giant unilamellar vesicles equipped with membrane proteins mimicking cell architecture. ACS Synth Biol 7(9):2116–2125

Tu Y, Peng F, Sui X, Men Y, White PB, van Hest JCM, Wilson DA (2017) Self-propelled supramolecular nanomotors with temperature-responsive speed regulation. Nat Chem 9(5):480–486

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moreno, S., Voit, B. & Gaitzsch, J. The chemistry of cross-linked polymeric vesicles and their functionalization towards biocatalytic nanoreactors. Colloid Polym Sci 299, 309–324 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00396-020-04681-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00396-020-04681-w