Abstract

Using computer simulations based on three separate data generating processes, I estimate the fraction of elections in which sincere voting is a core equilibrium given each of eight single-winner voting rules. Additionally, I determine how often each rule is vulnerable to simple voting strategies such as ‘burying’ and ‘compromising’, and how often each rule gives an incentive for non-winning candidates to enter or leave races. I find that Hare is least vulnerable to strategic voting in general, whereas Borda, Coombs, approval, and range are most vulnerable. I find that plurality is most vulnerable to compromising and strategic exit (causing an unusually strong tendency toward two-party systems), and that Borda is most vulnerable to strategic entry. I use analytical proofs to provide further intuition for some of my key results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Specifically, if there are more than two candidates for a single office, and a non-dictatorial election method allows voters to rank the candidates in any order, then there must be some profile of voter preferences under which at least one voter can get a preferred result by voting insincerely. This well-known ‘Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem’ relies in turn on the even more well-known ‘Arrow theorem’; for this, see Arrow (1951, rev. ed. 1963).

Nitzan (1985), Kim and Roush (1996), Smith (1999), Saari (1990) and Kelly (1993) all use an ‘impartial culture’ (IC) model, while Lepelley and Mbih (1994), Favardin et al. (2002), and Favardin and Lepelley (2006) use an ‘impartial anonymous culture’ (IAC) model. Tideman (2006) uses a data set consisting of 87 elections. On the other hand, Chamberlin (1985) uses both spatial model and an impartial culture model, Pritchard and Wilson use both IC and IAC, and Lepelley and Valognes (2003) use a somewhat more general model that has IC and IAC as two of its special cases.

Osborne and Slivinski (1996) focus on nomination equilibria given the plurality and runoff systems, with costs of entry and benefits of winning. Besley and Coate (1997) focus on nomination and voting equilibria given the plurality system. Moreno and Puy (2005, 2009) focus on positional voting rules, and show that plurality is unique among them in that it will elect the Condorcet winner among declared candidates when there are three or fewer potential candidates, although it will not necessarily do so when there are four or more. Another approach to strategic nomination is given by Tideman (1987), who shows that the addition or removal of ‘clone’ candidates may change the result given some voting rules, but not others.

In a result that is somewhat analogous to the Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem, Dutta et al. (2001) show that there will in some cases be downward pressure on the number of candidates (in the present paper, I will call this an incentive for ‘strategic exit’), given any ‘unanimous’ and non-dictatorial ranked ballot voting rule. (Note that this doesn’t apply to non-ranked systems like approval or range voting.)

For example, these may be assigned randomly, according to lexicographic or anti-lexicographic order, etc., but in any case they are exogenous, and known by the voters and candidates before the election.

This system is the application to the single-winner case of proportional representation by the single transferable vote, which is often named for Thomas Hare, who introduced the idea of successively eliminating the candidate with the fewest first choice votes. See ((Hoag and Hallett 1926, pp. 162–195))

See Coombs (1964). I note that some versions of Coombs include a provision to automatically elect a candidate who holds a majority of first choice votes, but I don’t use this provision here.

Condorcet (1785) describes the pairwise comparison method and the Condorcet winner. He also observes the possibility of a majority rule cycle emerging despite transitive voter preferences—this is known as the Condorcet paradox.

Black (1958, p. 175), develops the minimax method as a possible interpretation of Condorcet’s intended proposal. Levin and Nalebuff (1995) label this method as the “Simpson-Kramer min-max rule”; presumably this is due to Simpson (1969) and Kramer (1977). (Nurmi (1999), p. 18) refers to it as “Condorcet’s successive reversal procedure”. (Tideman (2006), p. 212) refers to it as “maximin”.

This terminology was used by Blake Cretney, on his currently-defunct web site Condorcet.org.

See Duverger (1964).

To be precise, the strong incentives for compromising and strategic exit make it highly likely that there will only be two ‘viable’ candidates in any particular plurality election. The two parties that these candidates belong to may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but once two parties have been established as dominant in any given jurisdiction, it is difficult for a third party to mount an effective challenge there. Cox (1997) refers to this as ‘local bipartism’.

This is similar to the model described in Chamberlin and Cohen (1978), but without inter-dimensional covariance.

The impartial culture model is defined, for example, in Nitzan (1985).

Here, I follow Tideman and Plassmann (2011).

This process creates 931 elections with three candidates, 1553 with four candidates, 1898 with five candidates, and 1764 with six candidates.

More detailed descriptions, along with the codes themselves, are available from the author on request.

It is also possible to ask how often groups of candidates may change the result in a way that they all prefer by either simultaneously entering or simultaneously exiting (thus, looking for core equilibria instead of Nash equilibria), but I omit this additional analysis in the interest of brevity, because its results don’t differ in any particularly interesting way from the results of the analysis already described.

A margin of error of \(\pm \).0098 is the upper bound, which applies when the true probability is exactly one half. I further reduce the random error in the difference between the scores that the various voting methods receive by using the same set of randomly generated elections for each method.

Despite the similar name, this is not equivalent to the impartial culture model. Rather, the IAC model supposes that every possible division of the voters among the \(C!\) possible preference orderings is equally likely.

This was also defined by Blake Cretney on Condorcet.org. Note that it is not the same as burying, compromising, or a combination of these, as it involves shifting votes from candidate q to candidate x in order to help candidate q.

See for example Beck (1975), who shows that ties are unlikely in large two-candidate elections; it is not hard to extend this intuition to the case of a pairwise tie within a multi-candidate election.

References

Aleskerov F, Kurbanov E (1999) Degree of manipulability of social choice procedures. In: Alkan et al. (eds) Current Trends in Economics. Springer, Berlin

Arrow K (1951, rev. ed. 1963) Social Choice and Individual Values

Beck N (1975) A note on the probability of a tied election. Public Choice 23(1):75–79

Besley T, Coate S (1997) An economic model of representative democracy. Q J Econ 112(1):84–114

Black D (1958) The Theory of Committees and Elections. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Brams S, Fishburn P (1978) Approval voting. Am Political Sci Rev 72(3):831–847

Brams S, Fishburn P (1983) Approval voting. Birkhäuser

Condorcet M de (1785) Essai sur l’application de l’analyse à la probabilité des décisions rendues à la pluralité des voix

Coombs C (1964) A Theory of Data. Wiley, New York

Chamberlin J, Cohen M (1978) Toward applicable social choice theory: a comparison of social choice functions under spatial model assumptions. Am Political Sci Rev 72(4):1341–1356

Chamberlin J (1985) An investigation into the relative manipulability of four voting systems. Behav Sci 30(4):195–203

Cox G (1997) Making votes count: strategic coordination in the world’s electoral systems. Cambridge university press, Cambridge

Dutta B, Jackson M, Le Breton M (2001) Strategic candidacy and voting procedures. Econometrica 69(4):1013–1037

Duverger M (1964) Political Parties: Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State. Methuen, London

Favardin P, Lepelley D, Serais J (2002) Borda rule, Copeland method and strategic manipulation. Rev Econ Des 7:213–228

Favardin P, Lepelley D (2006) Some further results on the manipulability of social choice rules. Soc Choice Welf 26:485–509

Gibbard A (1973) Manipulation of voting schemes: a general result. Econometrica 41:587–601

Green-Armytage J (2011) Four Condorcet-Hare hybrid methods for single-winner elections. Voting Matters 29:1–14

Hoag C, Hallett G (1926) Proportional Representation. MacMillan, New York

Kelly J (1993) Almost all social choice rules are highly manipulable, but a few aren’t. Soc Choice Welf 10(2):161–175

Kim KH, Roush FW (1996) Statistical manipulability of social choice functions. Group Decis Negot 5: 263–282

Kramer G (1977) A dynamical model of political equilibrium. J Econo Theory 16(2):310–334

Lepelley D, Mbih B (1994) The vulnerability of four social choice functions to coalitional manipulation of preferences. Soc Choice Welf 11(3):253–265

Lepelley D, Valognes F (2003) Voting rules, manipulability and social homogeneity. Public Choice 116: 165–184

Levin J, Nalebuff B (1995) An introduction to vote-counting schemes. J Econ Perspectives 9(1):3–26

McLean I, Urken A (1995) Class Soc Choice. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Moreno B, Puy S (2005) The scoring rules in an endogenous election. Soc Choice Welf 25:115–125

Moreno B, Puy S (2009) Plurality rule works in three-candidate elections. Theory Decis 67:145–162

Nitzan S (1985) The vulnerability of point-voting schemes to preference variation and strategic manipulation. Public Choice 47:349–370

Nurmi H (1999) Voting Paradoxes and How to Deal with Them. Springer, Berlin

Osborne M, Slivinski A (1996) A model of political competition with citizen-candidates. Q J Econ 111(1):65–96

Pritchard G, Wilson M (2007) Exact results on manipulability of positional voting rules. Soc Choice Welf 29:487–513

Saari D (1990) Susceptibility to manipulation. Public Choice 64:21–41

Saari D (2001) Chaotic Elections!. American Mathematical Society, Providence

Satterthwaite M (1975) Strategy-proofness and arrow’s conditions: existence and correspondence theorems for voting procedures and social welfare functions. J Econ Theory 10:187–217

Smith D (1999) Manipulability measures of common social choice functions. Soc Choice Welf 16:639–661

Simpson P (1969) On defining areas of voter choice: Professor Tullock on stable voting. Q J Econ 83(3): 478–490

Tideman TN (1987) Independence of clones as a criterion for voting rules. Soc Choice Welf 4(3):185–206

Tideman TN (2006) Collective Decisions and Voting: the Potential for Public Choice. Ashgate, Aldershot

Tideman TN, Plassmann F (2011) Modeling the Outcomes of Vote-Casting in Actual Elections. Manuscript http://bingweb.binghamton.edu/~fplass/papers/Voting_Springer.pdf. Accessed 12 Feb 2013

Tullock G (1967) Proportional representation. In Toward a Mathematics of Politics. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, pp 144–157

Woodall D (1997) Monotonicity of single-seat preferential election rules. Discret Appl Math 77:81–98

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix I: Tables

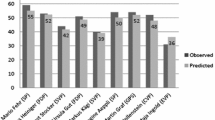

Appendix 2: Figures

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Green-Armytage, J. Strategic voting and nomination. Soc Choice Welf 42, 111–138 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-013-0725-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-013-0725-3