Abstract

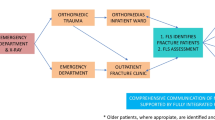

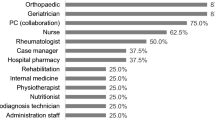

Fracture liaison services (FLS) have been shown to prevent efficiently subsequent fragility fractures (FF). However, very few studies have examined their implementation in depth. The purpose of this research was to identify factors influencing the implementation of a FLS at three sites in Quebec, Canada. From 2013 to 2015, individual and group interviews focused on experiences of FLS stakeholders, including implementation committee members, coordinators, and orthopaedic surgeons and their teams. Emerging key implementation factors were triangulated with the FLS patients’ clinico-administrative data. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research guided the analysis of perceived factors influencing four intervention outputs: investigation of FF risk (using the FRAX score), communication with the participant primary care provider, initiation of anti-osteoporosis medications (when relevant), and referral to organized fall prevention activities (either governmental or community based). Among the 454 FLS patients recruited to the intervention group, 83% were investigated for FF risk, communication with the primary care provider was established for 98% of the participants, 54% initiated medication, and 35% were referred to organized fall prevention activities. Challenges related to restricted rights to prescribe medication and access to organized fall prevention activities were reported. FLS coordinator characteristics to overcome those challenges included self-efficacy beliefs, knowledge of community resources, and professional background. This study highlighted the importance of enabling access to services for subsequent FF prevention, consolidating the coordinator’s role to facilitate a more integrated intervention, and involving local leaders to promote the successful implementation of the FLS.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Osteoporosis Canada (2019) Fast facts. https://osteoporosis.ca/about-the-disease/fast-facts/. Accessed 8 Sept 2019

Klotzbuecher CM et al (2000) Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res 15(4):721–739

Papaioannou A et al (2010) 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. Can Med Assoc J 182(17):1864–1873

Leslie WD et al (2012) A population-based analysis of the post-fracture care gap 1996–2008: the situation is not improving. Osteoporos Int 23(5):1623–1629

Grace SC et al (2013) Health-related quality of life and quality of care in specialized medicare-managed care plans. J Ambul Care Manage 36(1):72–84

Shibli-Rahhal A et al (2011) Testing and treatment for osteoporosis following hip fracture in an integrated U.S. healthcare delivery system. Osteoporos Int 22(12):2973–2980

Meadows LM et al (2007) The importance of communication in secondary fragility fracture treatment and prevention. Osteoporos Int 18(2):159–166

Raybould G et al (2018) Expressed information needs of patients with osteoporosis and/or fragility fractures: a systematic review. Arch Osteoporos 13(1):55

Cooper MS, Palmer AJ, Seibel MJ (2012) Cost-effectiveness of the concord minimal trauma fracture liaison service, a prospective, controlled fracture prevention study. Osteoporos Int 23(1):97–107

Leal J et al (2017) Cost-effectiveness of orthogeriatric and fracture liaison service models of care for hip fracture patients: a population-based study. J Bone Miner Res 32(2):203–211

Majumdar SR et al (2017) Economic evaluation of a population-based osteoporosis intervention for outpatients with non-traumatic non-hip fractures: the “Catch a Break” 1i [type C] FLS. Osteoporos Int 28(6):1965–1977

Moriwaki K, Noto S (2017) Economic evaluation of osteoporosis liaison service for secondary fracture prevention in postmenopausal osteoporosis patients with previous hip fracture in Japan. Osteoporos Int 28(2):621–632

Briot K (2017) Fracture liaison services. Curr Opin Rheumatol 29(4):416–421

Eisman JA et al (2012) Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res 27(10):2039–2046

Ganda K et al (2013) Models of care for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 24(2):393–406

Osuna PM, Ruppe MD, Tabatabai LS (2017) Fracture liaison services: multidisciplinary approaches to secondary fracture prevention. Endocrine Pract 23(2):199–206

Walters S et al (2017) Fracture liaison services: improving outcomes for patients with osteoporosis. Clin Interv Aging 12:117–127

Nakayama A et al (2016) Evidence of effectiveness of a fracture liaison service to reduce the re-fracture rate. Osteoporos Int 27(3):873–879

Cosman F et al (2014) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25(10):2359–2381

Akesson K et al (2013) Capture the fracture: a best practice framework and global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 24(8):2135–2152

Senay A et al (2016) Agreement between physicians’ and nurses’ clinical decisions for the management of the fracture liaison service (4iFLS): the Lucky Bone program. Osteoporos Int 27:1569–1576

Curtis JR, Silverman SL (2013) Commentary: the five Ws of a Fracture Liaison Service: why, who, what, where, and how? In osteoporosis, we reap what we sow. Curr Osteoporos Rep 11(4):365–368

Chandran M (2013) Fracture Liaison Services in an open system: how was it done? What were the barriers and how were they overcome? Curr Osteoporos Rep 11(4):385–390

Chandran M, Akesson K (2013) Secondary fracture prevention: plucking the low hanging fruit. Ann Acad Med Singapore 42(10):541–544

Drew S et al (2015) Implementation of secondary fracture prevention services after hip fracture: a qualitative study using extended normalization process theory. Implement Sci 10:57

Aizer J, Bolster MB (2014) Fracture liaison services: promoting enhanced bone health care. Curr Rheumatol Rep 16(11):455

Gaboury I et al (2013) Partnership for fragility bone fracture care provision and prevention program (P4Bones): study protocol for a secondary fracture prevention pragmatic controlled trial. Implement Sci 8:10-5908-8-10

Kanis JA et al (2001) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporosis Int 12(5):417–427

Giangregorio L et al (2006) Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap: an international phenomenon. Semin Arthritis Rheum 35(5):293–305

Leslie WD et al (2011) Construction of a FRAX(R) model for the assessment of fracture probability in Canada and implications for treatment. Osteoporos Int 22(3):817–827

Damschroder LJ et al (2009) Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 4:50

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288

Kvale S, Brinkmann S (2009) Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research reviewing. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J (2014) Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook, vol 3. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006) How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18(1):59–82

Roux S et al (2018) Using a sequential explanatory mixed method to evaluate the therapeutic window of opportunity for initiating osteoporosis treatment following fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int 29(4):961–971

Sale JE et al (2011) Systematic review on interventions to improve osteoporosis investigation and treatment in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int 22(7):2067–2082

Bell K, Strand H, Inder WJ (2014) Effect of a dedicated osteoporosis health professional on screening and treatment in outpatients presenting with acute low trauma non-hip fracture: a systematic review. Arch Osteoporos 9:167

Little EA, Eccles MP (2010) A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to improve post-fracture investigation and management of patients at risk of osteoporosis. Implement Sci 5:80

Boudou L et al (2011) Management of osteoporosis in fracture liaison service associated with long-term adherence to treatment. Osteoporos Int 22(7):2099–2106

Ruggiero C et al (2015) Fracture prevention service to bridge the osteoporosis care gap. Clin Interv Aging 10:1035–1042

Luc M et al (2018) Patient-related factors associated with adherence to recommendations made by a fracture liaison service: a mixed-method prospective study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(5):944

Patton MQ (2012) Essentials of utilization-focused evaluation. Sage, Angeles, p xxii, 461

Ham C (1995) International models of managed care. Health Care Manag 2(1):143–150

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants, Chantal Morin for her collaboration to data coding, and Meg Sears for editorial revisions.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [Grant number 201111PHE-267395-PHE-CFDA-01003-001] in partnership with the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Novartis, Amgen and the Centre de santé et de services sociaux—Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Sherbrooke (Centre intégré universitaire de santé et des services sociaux de l’Estrie-Centre hospitalier universitaire de Sherbrooke). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, the conduct of the research or the preparation or the submission of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcomes. Dr Boire would like to declare that, in the past 2 years, he has received funding from Merck Canada and from Amgen Canada for other research projects, as well as a remuneration from Merck Canada for a conference.

Ethical standards

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke on January 8th, 2013, and by relevant local ethics committees (Comité d’éthique de la recherche et de l’évaluation des technologies de la santé de l’Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal, CÉR du CSSS du Sud de Lanaudière, Comité d’éthique de la recherche du CSSS-IUGS, and Comité d’éthique de la recherche du CIUSSS du Centre-Sud-de-l’Île-de-Montréal; Comité d’éthique de la recherche de l’Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont, May 8th, 2013; CÉR du CSSS du Nord de Lanaudière and CÉR du CSSS du Roché Percé, October 31st, 2013; and Comité d’éthique de la recherche sur les sujets humains du Centre hospitalier universitaire de Montréal, November 20th, 2013). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. For confidentiality reasons, each study site has been represented by a number.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luc, M., Corriveau, H., Boire, G. et al. Implementing a fracture follow-up liaison service: perspective of key stakeholders. Rheumatol Int 40, 607–614 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04413-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04413-6