Abstract

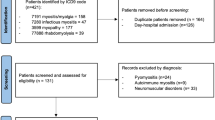

To evaluate the relevance of immunoglobulin (IVIg) and/or methylprednisolone pulse therapies in immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM). Secondarily, to analyze the muscle damage measured by late magnetic resonance images (MRI). This retrospective study included 13 patients with defined IMNM (nine patients positive for the anti-signal recognition particle and four patients positive for hydroxyl-methyl-glutaryl coenzyme A reductase) who were followed from 2012 to 2018. International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) scoring assessed the response to a standardized treat-to-target protocol with disease activity core-set measures and late magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The patients had a mean age of 53.5 years and were predominantly female and of white ethnicity. Median symptom and mean follow-up durations were 4 and 39 months, respectively. All patients received IVIg and/or methylprednisolone pulse therapies. All IMACS core-set measurements improved significantly after initial treatment. Nine patients achieved complete clinical response and among them 2 had complete remission. Eleven patients had discontinued glucocorticoid use by the end of the study. Only 2 patients had moderate muscle atrophy or fat replacement observed by MRI, with the remainder presenting normal or mild findings. Our patients with IMNM treated with an aggressive immunosuppressant therapy had a marked improvement in all IMACS core-set domains. Moreover, the MRI findings suggest that an early treat-to-target approach could reduce the odds of long-term muscle disability. Methylprednisolone and/or IVIg pulse therapies aiming at a target of complete clinical response are potential treatment strategies for IMNM that should be studied in future prospective studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dalakas MC (2015) Inflammatory muscle diseases. N Engl J Med 372:1734–1747

Dalakas MC (2011) Review: an update on inflammatory and autoimmune myopathies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 37:226–242

Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L (2015) Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep 17:72

Bronner IM, Hoogendijk JE, Wintzen AR, van der Meulen MF, Linssen WH, Wokke JH, de Visser M (2003) Necrotising myopathy, an unusual presentation of a steroid-responsive myopathy. J Neurol 250:480–485

Carroll MB, Newkirk MR, Sumner NS (2016) Necrotizing autoimmune myopathy: a unique subset of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. J Clin Rheumatol 22:376–380

Mammen AL, Pak K, Williams EK, Brisson D, Coresh J, Selvin E, Gaudet (2012) Rarity of anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase antibodies in statin users, including those with self-limited musculoskeletal side effects. Arthritis Care Res 64:269–272

Mammen AL, Tiniakou E (2015) Intravenous immune globulin for statin-triggered autoimmune myopathy. N Engl J Med 373:1680–1682

Hengstman GJ, ter Laak HJ, Vree Egberts WT, Lundberg IE, Moutsopoulos HM, Vencovsky J, Doria A, Mosca M, van Venrooij WJ, van Engelen BG (2006) Anti-signal recognition particle autoantibodies: marker of a necrotising myopathy. Ann Rheum Dis 65:1635–1638

Kao AH, Lacomis D, Lucas M, Fertig N, Oddis CV (2004) Anti-signal recognition particle autoantibody in patients with and patients without idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Arthritis Rheum 50:209–215

Grable-Esposito P, Katzberg HD, Greenberg SA, Srinivasan J, Katz J, Amato AA (2010) Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with statins. Muscle Nerve 41:185–190

Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Carrino JA, Lahouti AH, Basharat P, Albayda J, Paik JJ, Ahlawat S, Danoff SK, Lloyd TE, Mammen AL, Christopher-Stine L (2017) Thigh muscle MRI in immune-mediated necrotising myopathy: extensive oedema, early muscle damage and role of anti-SRP autoantibodies as a marker of severity. Ann Rheum Dis 76:681–687

Zheng Y, Liu L, Wang L, Xiao J, Wang Z, Lv H, Zhang W, Yuan Y (2015) Magnetic resonance imaging changes of thigh muscles in myopathy with antibodies to signal recognition particle. Rheumatology 54:1017–1024

Christopher-Stine L, Casciola-Rosen LA, Hong G, Chung T, Corse AM, Mammen AL (2010) A novel autoantibody recognizing 200-kd and 100-kd proteins is associated with an immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Arthritis Rheum 62:2757–2766

Mammen AL, Pak K, Williams EK, Brisson D, Coresh J, Selvin E, Gaudet D (2012) Rarity of anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase antibodies in statin users, including those with self-limited musculoskeletal side effects. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64:269–272

Miller T, Al-Lozi MT, Lopate G, Pestronk A (2002) Myopathy with antibodies to the signal recognition particle: clinical and pathological features. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 73:420–428

Suzuki S, Nishikawa A, Kuwana M, Nishimura H, Watanabe Y, Nakahara J, Hayashi YK, Suzuki N, Nishino I (2015) Inflammatory myopathy with anti-signal recognition particle antibodies: case series of 100 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis 10:61

De Souza FHC, Miossi R, Shinjo SK (2017) Necrotising myopathy associated with anti-signal recognition particle (anti-SRP) antibody. Clin Exp Rheumatol 35:766–771

Lundberg IE, Tjärnlund A, Bottai M et al (2017) 2017 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Ann Rheum Dis 76:1955–1964

Cruellas MG, Viana VS, Levy-Neto M, Souza FHC, Shinjo SK (2013) Myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibody profiles and their clinical associations in a large series of patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Clinics 68:909–914

Rider LG, Koziol D, Giannini EH, Jain MS, Smith MR, Whitney-Mahoney K, Feldman BM, Wright SJ, Lindsley CB, Pachman LM, Villalba ML, Lovell DJ, Bowyer SL, Plotz PH, Miller FW, Hicks JE (2010) Validation of manual muscle testing and a subset of eight muscles for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 62:465–472

Bruce B, Fries JF (2003) The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: a review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation. J Rheumatol 30:167–178

Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY (1982) The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol 9:789–793

Isenberg DA, Allen E, Farewell V, Ehrenstein MR, Hanna MG, Lundberg IE, Oddis C, Pilkington C, Plotz P, Scott D, Vencovsky J, Cooper R, Rider L, Miller F, International Myositis and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) (2004) International consensus outcome measures for patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Development and initial validation of myositis activity and damage indices in patients with adult onset disease. Rheumatology 43:49–54

Oddis CV, Rider LG, Reed AM, Ruperto N, Brunner HI, Koneru B, Feldman BM, Giannini EH, Miller FW, International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (2005) International consensus guidelines for trials of therapies in the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Arthritis Rheum 52:2607–2615

Aggarwal R, Rider LG, Ruperto N et al (2017) 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria for minimal, moderate, and major clinical response in adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: An International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation Collaborative Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 76:792–801

Pestronk A (2011) Acquired immune and inflammatory myopathies: pathologic classification. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23:595–604

Preuβe C, Goebel HH, Held J, Wengert O, Scheibe F, Irlbacher K, Koch A, Heppner FL, Stenzel W (2012) Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy is characterized by a specific Th1-M1 polarized immune profile. Am J Pathol 181:2161–2171

Basta M, Kirshbom P, Frank MM, Fries LF (1989) Mechanism of therapeutic effect of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Attenuation of acute, complement-dependent immune damage in a guinea pig model. J Clin Invest 84:1974–1981

Dalakas MC, Illa I, Dambrosia JM, Soueidan SA, Stein DP, Otero C, Dinsmore ST, Mccrosky S (1993) A controlled trial of high-dose intravenous immune globulin infusions as treatment for dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med 329:1993–2000

Ballow M (1991) Mechanisms of action of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and potential use in autoimmune connective tissue diseases. Cancer 68:1430–1436

Dwyer JM (1992) Manipulating the immune system with immune globulin. N Engl J Med 326:107–116

Funding

This work was funded by: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) #2017/13109-1 and Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo to S.K.S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jean Marcos de Souza, Leonardo Santos Hoff and Samuel Katsuyuki Shinjo declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Brief report of the analyzed subjects

Patient 1

Afro-descendant female with 66 years old complaining of muscle weakness, weight loss and fatigue starting days after statin use. The serum creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels were around 3000 U/L and the manual muscle test with eight muscle groups (MMT-8) was 50. She was promptly treated with 3 days of methylprednisolone (MP), 1 g each day, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), 2 g/kg, divided in 2 days and oral prednisone, 0.5 mg/kg/day. After 1 month, she returned feeling subjective improvement, but the MMT-8 was nearly unchanged and she maintained CPK levels at 1093 U/L. New MP and IVIg pulse therapy was prescribed, prednisone was tapered to 0.25 mg/kg/day and methotrexate 15 mg/week was begun. A few days later, the patient evolved with pneumonia and urinary tract infection, warranting hospital admission, but treated without major complications. One month later, she returned to the outpatient clinic with normal muscle strength and CPK levels within normal ranges. No disease relapsing was ever noticed and prednisone was completely withdrawn 5 months after the beginning of the treatment. Unfortunately, this patient died before acquisition of the MRI. The cause of death was sudden cardiac arrest, unrelated to the immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy.

Patient 2

Caucasian man with 66 years old complaining of subtle muscle weakness. He was using statins for 2 years. The initial CPK was 4300 U/L and the MMT-8 was 55. He was promptly treated with 3 days of MP, 1 g each day, IVIg, 2 g/kg, divided in 2 days and oral prednisone, 0.25 mg/kg/day. Two months after the initial treatment he returned with normal muscle strength and a CPK level of 181 U/L. He was then started on methotrexate, that was adjusted until 25 mg/week and started the tapering of the prednisone that was concluded 7 months later. No flares were reported and he could withdraw the immunosuppressive drug within 36 months. The MRI was obtained 44 months after disease onset depicting no relevant alterations.

Patient 3

Female afro-descendant of 55 years old that presented myalgia right after the introduction of simvastatin. Five months later, despite having ceased statin use she started feeling a mild muscle weakness and exams showed an elevated serum CPK (around 100.000 U/L). The MMT-8 assessment summed 74 points. MP was prescribed for 3 days, 1 g per day, followed by oral prednisone, 0.5 mg/kg/day. IVIg was unavailable at the time of induction. One month later, the patient was reassessed presenting normal muscle strength and a CPK of 224 U/L. Prednisone tapering started and methotrexate was prescribed. The dose of the immunosuppressive drug was adjusted until 25 mg/week and prednisone was totally removed 7 months after the induction. Within 40 months, methotrexate was stopped. No disease relapsing occurred. MRI was obtained 41 months after disease onset with only mild fat replacing and muscle atrophy.

Patient 4

A 63 years old female was using fibrates for a few months. The drug was stopped when she complained of muscle pain. Eight months later, the pain persisted and she evolved with muscle weakness (MMT-8 of 60) and a CPK of 8342 U/L. She was treated with 3 days of MP, 1 g each day, IVIg, 2 g/kg, divided in two days and oral prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day. One month after, she was still felling weak, the MMT-8 summed 69 and CPK levels were around 1500 U/L. The induction protocol was, thus, repeated and prednisone was tapered to 0.5 mg/kg/day. After another month, the patient returned with improving muscle strength (MMT-8 of 78) and CPK levels of 603 U/L. Azathioprine was started and prednisone tapering progressed. During the course of treatment, the patient had to exchange azathioprine to mycophenolate mofetil due to elevated liver enzymes. Prednisone was completely withdrawn within 6 months. One year after the exchange to mycophenolate, the patient complained of blurred vision that she attributed to the drug. She was then switched to methotrexate that she used until a total time of 19 months of immunosuppression. The MRI was obtained with 40 months of disease length, many months after drug withdrawal, showing only mild fat replacement.

Patient 5

A healthy 42 years old male of Afro-descendant family started experiencing subtle muscle weakness some weeks after statin introduction. Four months later he arrived to the service with nearly normal muscle strength (MMT-8 of 75) and CPK levels of 18,350 U/L. He was promptly treated with 3 days of MP, 1 g each day, IVIg, 2 g/kg, divided in 2 days, oral prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day, and methotrexate, 15 mg/week. One month later, he maintained the same MMT-8 and CPK of 3159 U/L. The protocol was repeated, methotrexate was adjusted to maximal dosage (25 mg/week) and prednisone was tapered to 0.25 mg/kg/day. Another month passed and he returned with similar findings; another round of induction was prescribed and azathioprine (1.5 mg/kg/day) was associated. He was assessed again with a modest gain in MMT-8 (78) and CPK levels of 1265 U/L. By this moment, prednisone was tapered to 10 mg/day and the patient was assigned to receive rituximab due to resistant disease. While the patient waited to rituximab, he received in different occasions 6 IVIg or MP pulse therapies. This patient never reached normal levels of CPK or substantial recovery in muscle strength. The MRI was obtained 14 months after symptoms onset and revealed mild muscle edema, suggesting disease activity, but no atrophy or fat replacement.

Patient 6

A Caucasian male of 62 years was just started on statins presented to our outpatient clinic with 4 months of muscle weakness and pain. His CPK levels were around 16,000 U/L and his MMT-8 summed 70. This patient was diabetic and considered of elevated cardiovascular risk by his cardiologist, so he was assigned to receive only IVIg, 2 g/kg, as induction. One month later, the patient returned with CPK levels of 4000 U/L and maintained muscle weakness. Another round of induction was prescribed, and the patient was started on azathioprine, 2.0 mg/kg/day. After 2 months, CPK levels were 2800 U/L and the pain subsided, but the patient still maintained weakness (MMT-8 of 76). Our service decided to associate methotrexate 10 mg/week to his treatment and to perform another round of induction with IVIg. After one month, the patient was reassessed with normal muscle strength, but CPK levels were still elevated (2500 U/L). Since he was asymptomatic, it was assumed that the patient reached clinical response and pulse therapies were ceased, in spite of the elevated CPK. The MRI was obtained 16 months after the disease onset and showed mild fat replacement and mild edema.

Patient 7

A female patient of 56 years old and Caucasian ethnicity presented with 3 months of mild muscle weakness (MMT-8 of 78) and elevated levels of CPK (around 7000 U/L). Before referral to our service, she was treated with prednisone 1 mg/kg/day for 1 month. Since the patient was diabetic, she was spared from intravenous glucocorticoid, receiving only IVIg, 2 g/kg, methotrexate, 15 mg/week, and maintaining the prednisone. Two months after induction, the patient was admitted with a respiratory distress syndrome attributed to pneumonia. After an initial course of antibiotics and withdrawal of methotrexate, as a possible source of lung injury, she recovered and the drug was switched to mycophenolate. After 1 month, the patient returned to the outpatient clinic with preserved muscle strength and normal CPK levels. By this moment, tapering of prednisone was started and completed 18 months later. No flares were reported. MRI was performed 48 months after disease onset with normal findings.

Patient 8

An Asiatic male patient of 52 years old experienced muscle weakness (MMT-8 of 71) and CPK elevation (until 7000 U/L) after introduction of rosuvastatin by his cardiologist. He was treated with IVIg (2 g/kg) and prednisone 20 mg/day. No intravenous glucocorticoid was used due to diabetes mellitus and presumed elevated cardiovascular risk. After 1 month, CPK levels were still high and it was decided to repeat the IVIg, to maintain the oral glucocorticoid and to add azathioprine (2.0 mg/kg/day). After another month, CPK levels returned to normal (80 U/L), but the patient still complained of muscle weakness and pain. By this moment, it was decided to associate methotrexate (10 mg/week) to the treatment and to start prednisone withdrawal. The patient returned the next month with normal MMT-8 and CPK and further reduction of prednisone was attempted, from 10 mg to 5 mg per day. Two months later, the patient returned with stable muscle activity, but presented dyspnea and pulmonary infiltrate, attributed presumably to the myopathy. During the next 5 months, although no muscle inflammation was perceived, the patient was first started on mycophenolate and afterward assigned to 4 intravenous pulses of cyclophosphamide to treat the respiratory symptoms, without success. In the end of this protocol of cyclophosphamide induction, muscle activity relapsed, with new onset of muscle enzymes elevation (up to 1758 U/L). Another round of IVIg was prescribed and prednisone was maintained at 5 mg/day. During the infusion of this cycle of IVIg, the patient presented a mild anaphylactic reaction, controlled with hydrocortisone, anti-histaminic drugs and adjustment of the infusion time. By this point, the patient was candidate to rituximab, especially due to lung disease. After starting rituximab, the lung parameters improved and the patient was asymptomatic. Prednisone was fully removed 50 months after the beginning of the treatment. The MRI, obtained 66 months after disease onset, showed only mild fat replacement.

Patient 9

A 49 years old Caucasian female presented with 1 month of fever and weakness. The initial assessment showed a CPK of 3707 U/L and a MMT-8 of 60. She was treated with 3 days of MP, 1 g each day, IVIg, 2 g/kg, divided in 2 days and oral prednisone, 0.5 mg/kg/day. After 1 month, the patient was still feeling weak, with a MMT-8 with minor improvement and a CPK of 1186 U/L. It was decided to repeat the induction and to start prednisone tapering. The patient returned 1 month later with muscle strength preserved and a CPK of 52 U/L. Thus, she was assigned to methotrexate, 15 mg/week, and prednisone reduction was progressed. After adjustment of methotrexate to maximal dosage (25 mg/week), the patient presented mild hepatic toxicity and the drug was switched to azathioprine (2.0 mg/kg/day). No more muscle activity was ever reported and the patient was free from prednisone after 17 months of treatment. MRI was acquired 23 months after disease onset and depicted only mild fat replacement.

Patient 10

A female patient of Asiatic ascendance with 77 years was using statin for a few months when started presenting fatigue, weakness and weight loss. Physical examination showed a MMT-8 of 68 and laboratory evaluation showed a CPK of 11,350. Due to previous diabetes mellitus and advanced age, she was assigned to receive only IVIg, 2 g/kg. After 2 months, the patient presented weight gain, but maintained elevated levels of CPK (3800 U/L) and unaltered muscle strength. Thus, it was decided to repeat the induction protocol and to associate azathioprine, 2.0 mg/kg/day. After 1 month, the patient returned asymptomatic and with lower CPK levels (around 1900 U/L). Although the patient maintained persistently elevated muscle enzymes, strength was always preserved and the induction protocol was not repeated thus far. The MRI was obtained with 11 months of disease length and no alterations were observed.

Patient 11

A Caucasian female of 35 years old that was otherwise healthy presented with 6 months of muscle weakness and CPK levels up to 26,000 U/L. She was initially treated outside our service, with methylprednisolone pulses (3 g divided in 3 days) and prednisone 1 mg/kg/day. Maintaining muscle weakness, she received 1 cycle of rituximab 9 months after disease onset. The patient arrived to our outpatient clinic within 14 months after the disease beginning with a MMT-8 of 54 and CPK levels around 3000 U/L. She was treated with 3 days of MP, 1 g each day, IVIg, 2 g/kg, divided in 2 days, azathioprine (2 mg/kg) and prednisone was tapered to 0.25 mg/kg/day. For the next 4 months, the patient would receive 2 pulses of MP and IVIg combined, 1 pulse of isolated MP and 1 pulse of isolated IVIg, until finally regain muscle strength and return muscle enzymes values closer to normality (around 1000 U/L). Maintenance therapy was achieved with azathioprine (2.0 mg/kg/day) and rituximab every 6 months. Prednisone cessation was concluded 52 months after initiation and MRI was acquired after 56 months of disease length. The former showed the greatest degree of fat replacement of the sample, considered moderate.

Patient 12

An afro-descendant young female of 26 years that was otherwise healthy presented with rapid onset muscle weakness that lasted 1 month. Her MMT-8 summed 68 and her CPK levels were 14,000 U/L. She was promptly treated with 3 days of MP, 1 g each day, IVIg, 2 g/kg, divided in two days, prednisone, 1.0 mg/kg/day, and azathioprine, 2.0 mg/kg/day. Since the patient had a poor educational and socioeconomic condition and frequently missed visits, skipped doses and manipulated medications on her own, it was decided to maintain methotrexate as maintenance, since the weekly administration could eventually improve adherence. Four months later, after many dosing adjustments and reorientation, the patient sustained muscle weakness and CPK levels were around 2000 U/L with methotrexate 20 mg/week and 1.0 mg/kg/day of prednisone. It was decided to repeat the IVIg infusion, at the same dose. One month later, almost no result was achieved and another round of combined MP and IVIg was prescribed. After another month, the patient returned with improved muscle strength (MMT-8 of 74) and CPK levels near normality (approximately 800 U/L). Prednisone tapering was finally started, and methotrexate was adjusted to full-dose. Two months later, the patient returned with subjective sensation of weakness, but without CPK elevations or alterations on physical examination. It was decided to associate cyclosporine, 2 mg/kg/day. In the next visit, the patient reported that skipped many doses of the immunosuppressive drugs and the weakness had returned. Indeed, her MMT-8 dropped to below 60 points and CPK levels once again raised to beyond 3000 U/L. Another round of MP and IVIg was prescribed and the patient was assigned to rituximab in association with methotrexate. In the next months, before approval and adequate prophylaxis for the biologic, the patient deteriorated muscle activity, needing monthly pulses of IVIg to sustain muscle strength. Even after 2 cycles of rituximab, the patient sustained elevated levels of CPK and muscle strength stabilized, but no gains were achieved. Prednisone was never completely tapered and the MRI, obtained within 33 months of the disease onset, showed active edema and fat replacement, surprisingly quantified as mild. It is important to highlight, though, that lack of adherence to the treatment schemes was remarkably high in this case, contributing to the poor prognosis.

Patient 13

The patient #13 is a previously healthy Caucasian woman of 45 years old that presented with progressive fatigue over a year that, in the last 5 months, evolved to proximal muscle weakness and dysphagia. She arrived to our outpatient clinic with a MMT-8 of 69 and CPK levels of 13,600 U/L. She was promptly treated with 3 days of MP, 1 g each day, IVIg, 2 g/kg, divided in two days and prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day. After 1 month, she returned with some improvement in dysphagia, but maintaining muscle weakness and a serum CPK of 1161 U/L. Another round of MP and IVIg was prescribed and prednisone tapering commenced. Another month passed and she returned with an important improvement in muscle strength (MMT-8 of 78) and normal CPK levels (272 U/L). At this point, methotrexate was started at 15 mg/week and prednisone was once again tapered to 0.25 mg/kg/day. Four months later, the patient returned with a mild increase in CPK levels (up to 500 U/L), but asymptomatic. It was decided to associate azathioprine (2.0 mg/kg/day) to the previous schema. Further prednisone tapering was also attempted. The treatment was successful, and the oral glucocorticoid was fully removed 28 months after the beginning of the treatment, without new flares. By the 36th month of treatment, the patient presented a mild elevation of liver enzymes and lymphopenia; thus, the maintenance schema was switched to mycophenolate, that the patient did not tolerate due to side effects, and finally to cyclosporine (3 mg/kg/day), the final drug before MRI acquisition. The former was obtained within 63 months of the disease onset and showed moderate fat replacement, without atrophy or edema.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Souza, J.M., Hoff, L.S. & Shinjo, S.K. Intravenous human immunoglobulin and/or methylprednisolone pulse therapies as a possible treat-to-target strategy in immune-mediated necrotizing myopathies. Rheumatol Int 39, 1201–1212 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04254-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04254-3