Abstract

TP53 aberrations reportedly predict favorable responses to decitabine (DAC) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). We evaluated clinical features and outcomes associated with chromosome 17p loss or TP53 gene mutations in older, unfit DAC-treated AML patients in a phase II trial. Of 178 patients, 25 had loss of 17p in metaphase cytogenetics; 24 of these had a complex (CK+) and 21 a monosomal karyotype (MK+). In analyses in all patients and restricted to CK+ and MK+ patients, 17p loss tended to associate with higher rates of complete remission (CR), partial remission (PR), or antileukemic effect (ALE). Despite favorable response rates, there was no significant OS difference between patients with or without loss of 17p in the entire cohort or in the CK+ and MK+ cohort. TP53 mutations were identified in eight of 45 patients with material available. Five of the eight TP53-mutated patients had 17p loss. TP53-mutated patients had similar rates of CR/PR/ALE but shorter OS than those with TP53 wild type (P = 0.036). Moreover, patients with a subclone based on mutation data had shorter OS than those without (P = 0.05); only one patient with TP53-mutated AML had a subclone. In conclusion, 17p loss conferred a favorable impact on response rates, even among CK+ and MK+ patients that however could not be maintained. The effect of TP53 mutations appeared to be different; however, patient numbers were low. Future research needs to further dissect the impact of the various TP53 aberrations in HMA-based combination therapies. The limited duration of favorable responses to HMA treatment in adverse-risk genetics AML should prompt physicians to advance allografting for eligible patients in a timely fashion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The hypomethylating agents (HMA) decitabine (DAC) and azacitidine (AZA) are a standard of care in AML and higher risk MDS patients not eligible for intensive treatment. While dynamic features, such as early platelet response [1], can be used to estimate eventual treatment response, no pre-treatment markers are in routine clinical use.

Several studies reported associations between outcomes of patients with MDS or AML receiving HMAs and genetic aberrations, DNA methylation, mRNA or microRNA expression, or other markers (e.g., HbF) [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Among these, we described that patients with AML or MDS and a monosomal karyotype (MK+) benefitted from DAC treatment, particularly when multiple monosomies were present. [3, 9, 15] The MK+ status is closely associated with the presence of a complex karyotype (CK+) [15], and MK+ and CK+ are associated with mutations in TP53 [16,17,18,19]. In turn, TP53 mutations have also been recently reported to be predictive for response in patients with MDS or AML treated with DAC [11, 14]. Moreover, among patients with chromosome 17p aberrations, those treated with AZA tended to have a better overall survival (OS) than those treated with conventional care regimens [16].

Here, we evaluated the genetic and clinical characteristics associated with loss of chromosome 17p or gene mutations affecting TP53 in older, unfit AML patients treated with DAC within a phase II trial.

Patients and methods

Patients and treatment

Patients were enrolled onto the phase II trial 00331 (German Clinical Trials Registry DRKS00000069), the results of which have been previously reported [3]. Briefly, 227 patients with AML (by French-American-British classification), who were ineligible for intensive chemotherapy, were treated with DAC (15 mg/m2 every 8 h for 3 consecutive days, total dose of 135 mg/m2, every 6 weeks). In case of an antileukemic effect (ALE) or stable disease (SD) after course 1, administration of the second course of DAC was followed by all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA; 45 mg/m2/day) for 28 days. Patients with complete remission (CR), partial remission (PR), or ALE after completion of 4 courses were eligible to receive maintenance treatment with DAC at 20 mg/m2/day (for 3 consecutive days, every 6–8 weeks). Bone marrow aspirates were performed after courses 1, 2, and 4. Morphology was centrally reviewed. The following response definitions were applied [3]: CR: BM blasts < 5%, platelets > 100 × 109/L, white blood cells (WBC) > 1.5 × 109/L, and no extramedullary leukemia. PR: BM blasts 5–25%, platelets > 100 × 109/L, WBC > 1.5 × 109/L, and no clinical or imaging evidence of leukemia; or BM blasts < 5%, platelet count < 100 × 109/L, WBC < 1.5 × 109/L. ALE: > 25% reduction of BM blasts relative to the initial blast percentage but not enough to fulfill the criteria for a PR. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of each center. All patients had given written informed consent for collection and use of data and specimens. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee and with the Helsinki Declaration.

Cytogenetics and gene mutations

Metaphase karyotypes were centrally reviewed and CK+ and MK+ status assigned as previously described [3, 15]. MK+ required presence of a single autosomal monosomy and a structural aberration, or two or more autosomal monosomies [15]. Loss of 17p was evaluated based on the available karyotype data.

Data on mutations in DNMT3A and NPM1 and FLT3-internal tandem duplications (ITD) had been previously reported [17]. For the present study, bone marrow (n = 27) and peripheral blood (n = 18) samples of 45 patients were analyzed using the Illumina TruSight Myeloid Sequencing Panel (covering 54 genes relevant in myeloid neoplasms) for library preparation and an Illumina MiSeq device for sequencing. Variants located in introns, synonymous variants, and known single nucleotide polymorphisms were excluded. Variants had to feature a variant allele frequency (VAF) of > 5% for missense variants, or had to be hot spot mutations or mutations known to be present in the given patient, or had to be large insertions or deletions. Variants had to be covered by > 100 reads, and the variant had to be observed in > 10 reads. Four of six amplicons covering CEBPA only gave insufficient reads for analysis, thus CEBPA mutations may be underestimated. The genetic data were used to derive the clonal architecture (detailed in the supplemental).

Statistical analyses

CR, PR, ALE, SD, progressive disease (PD), early death (ED). and OS (time from start of treatment to death) were defined as previously described. [3] All patients who had received at least one dose of DAC were included in the analysis. The Fisher’s exact and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare categorical or continuous variables, respectively. Estimated probabilities of OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Group differences were assessed using the log-rank test and univariate Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

Association of loss of 17p with pre-treatment characteristics and outcomes

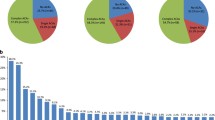

As previously published, [3] cytogenetic data were available for 177 patients; 120 patients had clonal cytogenetic aberrations. Of these, 25 patients were identified to have loss of 17p; 24 of them were CK+, and 21 were MK+ (Table 1).

We evaluated the outcome of patients with loss of 17p compared with those without in the entire cohort of patients with cytogenetic data and in the subgroups of CK+ or MK+ patients (Table 2, Fig. 1a–c). Patients with loss of 17p overall tended to have favorable response rates in comparison with patients without loss of 17p (CR/PR/ALE vs SD/PD/ED, P = 0.08). This was also true when analyses were conducted only among patients with CK+ (P = 0.01) or MK+ (P = 0.05). However, despite these favorable response rates and although the median OS was longer for patients with loss of 17p especially in the CK+ and MK+ cohort, there was no significant difference in the OS between patients with or without loss of 17p in the entire cohort or in the CK+ and MK+ cohort, as the OS curves crossed shortly after the 6-month mark.

Overall survival according to a-c the presence or absence of loss of 17p among a all patients with cytogenetic information, b patients with CK+ and c patients with MK+, and overall survival according to d the presence or absence of a TP53 mutation among all patients with samples subjected to panel sequencing (corresponding COX model: HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.03–5.16, P = 0.041), e the presence or absence of minor subclones among patients with available data (corresponding COX model: HR 2.29, 95% CI 0.98–5.39, P = 0.056), and f the presence of a TP53 mutation or a minor subclone or absence of both among patients with available data (corresponding COX model: HR 2.63, 95% CI 1.20–5.79, P = 0.016)

Of the patients with cytogenetic data, 77 had received ATRA in addition to DAC, 49 of them over the entire planned period of 4 weeks during course 2. Only six of the 49 patients had a loss of 17p. The low number of patients and the bias regarding the selection of patients receiving ATRA precluded further analyses.

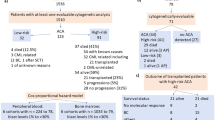

Gene mutation profiles and clonal architecture

Among the 45 patients with samples available for sequencing, the median age was 75 years (range, 63–83), and 27 (60%) had AML secondary to MDS. We identified a median of three mutations (range, 0–9) or three mutated genes (range, 0–6) per patient, respectively; nine patients had more than one mutation in a given gene, and in three (7%) patients, no mutations were identified (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table S2). Most frequently mutated genes were ASXL1 (29% of patients), RUNX1 (24%), SRSF2 (24%), IDH1 (9%) or IDH2 (13%), TET2 (18%), and TP53 (18%).

Genetics in AML patients analyzed via panel sequencing. Each line represents a patient, and each column contains the genetic information as indicated. Patients are ordered by the presence of a TP53 mutation and/or loss of 17p, and then by the mutation status of the remaining genes according to their order in the columns. In case of mutated genes, the variant allele frequency (VAF) is indicated: VAF > 25%, red; 11–25%, orange; ≤ 10%, light orange. If a gene harbored more than one mutation in a patient, the VAF of each mutation is provided. Wild-type sequence is color-coded in green. Rarely mutated genes are summarized in a column called other and the gene name is specified in the cell. For mutations in FLT3, the localization is specified: ITD, internal tandem duplication in the juxtamembrane (JM) domain; JM, point mutations in the JM domain; TKD, point mutations in tyrosine kinase domain. The presence of a minor subclone is indicated in red, its absence in green. Missing data are color-coded in gray

Based on the sequencing and cytogenetic data, the clonal architecture could be derived in 33 patients (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table S2). In nine patients, one or more minor subclones (defined through mutations present in a cell fraction that was > 20% smaller than the major clone) were present; while in the remaining 24 patients, no subclones in addition to the major clone could be identified.

Genetic and clonal features of the TP53 mutations

The TP53 mutations were located in exons 4 (n = 2), 5 (n = 3), 7 (n = 3), and 10 (n = 1) (Supplemental Table S2); one patient had two mutations. Three TP53 mutations were truncating, the remaining were missense substitutions.

Five patients with a TP53 mutation also had a cytogenetic loss of 17p. In one of these patients, the VAF of the TP53 mutation indicated the loss of the TP53 wild-type allele (i.e., VAF > 60%); one other patient with loss of 17p had two mutations in TP53. One patient with a TP53 mutation with a VAF > 60% had no chromosome 17 aberration by metaphase karyotyping. TP53-mutated AMLs more often were CK+ (P < 0.001), MK+ (P = 0.02), or harbored a loss of 17p (P < 0.001) than TP53 wild-type AML (Table 3).

The TP53 mutations were all present in the major AML clone of the respective patient. Only one patient (13%) with a TP53-mutated AML had a minor subclone, while 8 (32%) of the patients with TP53 wild-type AML did. Patients with a TP53 mutation harbored a median of only one additional mutation (range, 0–4).

Association of TP53 mutations with clinical features and outcome

Compared with TP53 wild type, patients with TP53 mutations were younger (P = 0.01; median, 71 vs 77 years); AML with TP53 mutation tended to more often develop from antecedent MDS (P = 0.12) (Table 3).

In the outcome comparisons between AML patients with mutated or wild-type TP53, there were no differences in the response rates, but patients with TP53 mutations had a shorter OS than those with wild-type TP53 (P = 0.036) (Table 2, Fig. 1d).

Twenty-four of the patients with sequenced samples had received ATRA. Of these, only three harbored a TP53 mutation, which precluded outcome analyses.

Association between other mutations and outcome

Other markers previously reported to be associated with outcomes in DAC-treated patients are mutations in SRSF2, [11] DNMT3A, [2, 17] TET2, [7] IDH1, or IDH2. [8, 14] We found no differences in response rates or OS between patients with or without mutations in these genes or in at least one RNA splicing gene (data not shown). Moreover, there were no differences in response rates and OS between patients with ≤ 3 mutated genes and those with > 3 mutated genes (Supplemental Table S3).

However, the presence of subclones was associated with a shorter OS in comparison with their absence (P = 0.05) (Fig. 1e, Supplemental Table S3). Only one of the 9 patients with a minor subclone also harbored a TP53 mutation. Since both a TP53 mutation and presence of a minor subclone were associated with shorter OS, we combined patients with at least one of these features into one group and compared them with the remaining. Compared with patients with TP53 wild type and absence of a minor subclone, those with a TP53 mutation or a minor subclone expectedly had shorter OS (P = 0.01); no differences in the response rates were observed (Fig. 1f, Supplemental Table S3).

Discussion

HMAs have become a standard of care in AML patients not eligible for intensive chemotherapy. Chromosomal or molecular aberrations of TP53 are likely central in the investigation of markers and biological pathways associated with the response to HMAs [5, 7, 10,11,12, 14, 16, 18, 19]. Thus, we sought to investigate the impact of loss of 17p and TP53 mutations in our phase II trial 00331 in which older unfit AML patients were treated with 3-day DAC.

We observed that patients with a loss of 17p tended to have higher rates for CR/PR/ALE both in analyses including all patients and in those restricted to CK+ and MK+ patients. Among CK+ and MK+ patients, patients with loss of 17p also had longer median OS, but this favorable course could not be maintained over time. Patients with TP53-mutated AML had similar rates of CR/PR/ALE but shorter OS than those with wild-type TP53 (P = 0.036).

Published data on the impact of chromosome 17p aberrations on response to HMA treatment are scarce. Nazha et al. [20] observed no difference in the response rates according to chromosome 17 aberrations in MK+ and CK+ patients treated with HMAs. In an explorative retrospective analysis of the AZA-AML-001 study, patients with chromosome 17p aberrations had a strong trend for better OS when treated with AZA as compared with conventional care regimens (mainly low-dose cytarabine) [16].

The impact of TP53 mutations (or expression) on outcomes in HMA-treated MDS or AML patients has been assessed in several studies and yielded heterogeneous results. [7, 10,11,12, 14, 16, 19] Welch et al. [11] observed in patients with AML or MDS that achievement of CR was more frequent in patients with a TP53 mutation. Moreover, in contrast to the poor OS of TP53-mutated AML patients after standard induction, there was no OS difference according to TP53 mutation status in patients receiving DAC. In the aforementioned analysis of the AZA-AML-001 study, patients with TP53-mutated AML had strong trends for improved OS when treated with AZA compared with alternative therapies [16]. However, in studies among MDS patients treated with DAC or AZA, TP53 mutations had no impact on response rates but were associated with shorter response duration and/or OS [7, 10]. In another report on patients with MDS (mostly with blast excess) who received DAC, most patients with TP53 mutations achieved a CR, but they still had inferior OS [14].

In MDS, mono-allelic TP53 mutations associate with more favorable disease features (including less frequent complex karyotype and better OS) than multi-hit TP53 mutations [21]. The role of TP53 mutations under consideration of their allelic state remains to be established. Welch et al. [11] described that two-thirds of the patients with TP53 mutations potentially had both alleles affected. In our study, 5 patients fulfilled the criteria of a TP53 multi-hit mutation (i.e., multiple gene mutations or gene mutation plus genomic loss) according to Bernard et al. [21]. The low patient numbers precluded meaningful outcome analyses. Hopefully, future studies will be able to decipher the impact of the allelic state of TP53 and its impact in response to DAC.

Considering our results and those reported by others, it currently remains elusive whether the TP53 aberrations or rather associated genetic features may confer sensitivity to HMAs. As observed in the present study, TP53 mutations and chromosome 17p aberrations coincide with CK+ and MK+ [22,23,24,25,26]; and for trial 00331, which was subject to the present study, we previously reported that MK+ patients had higher response rates and similar OS compared with MK− patients [3]. Similar results have been reported by Wierzbowska et al. [27] from a post hoc analysis of the phase 3 DACO-016 trial in AML and by our group from the phase 3 EORTC trial 06011 in MDS [9, 28]. In the study by Welch et al. [11], almost all patients with TP53 mutations had unfavorable cytogenetics, and achieving a CR was more frequent in patients with unfavorable than those with intermediate or favorable cytogenetics. In the study by Chang et al. [14], almost all TP53-mutated patients who achieved a CR were CK+ or had monosomies.

Welch et al. [11] suggested that a variable response of TP53-mutated AML to DAC may be due to the presence of TP53 mutations in subclones instead of the major clone. We observed no superior response to DAC, although TP53 mutations were all present in the major clone, and despite other features supporting their disease-driving effect, i.e. TP53-mutated AML only rarely harbored a minor subclone and had a low number of additional mutations [7]. However, we did observe that patients with a minor subclone had shorter OS than those without, although only one of the nine patients with a minor subclone also harbored a TP53 mutation.

The heterogeneity in the reports on associations between TP53 aberrations and response to HMAs may be due to weaknesses that are variably shared by the studies, including the present study. First, analyses are often based on relatively small patient numbers [11, 14, 16]. Second, if provided, the information on 17p loss normally stems from conventional cytogenetics, although the (presumably lost) TP53 allele may be present in unidentified chromosome material. [16, 29] Third, cohorts variably comprise MDS or AML patients or both, although DAC may have higher efficacy in patients with higher blast counts [30, 31]. Fourth, there is the heterogeneity in treatment. In several studies, patients treated with DAC or AZA were combined into one group [7, 10], or patients were included who received DAC combined with another agent [2, 3, 7, 10]. Moreover, DAC was administered according to different protocols. The majority of the patients received DAC according to the 5-day protocol (total of 100 mg/m2 over 5 days) [10, 14]. In the study by Welch et al. [11], the majority of patients received DAC according to the 10-day protocol (total 200 mg/m2 over 10 days). Patients in our present study received DAC according to the 3-day protocol (total of 135 mg/m2 over 3 days; every 6 weeks), in part of the patients followed by a reduced dosage maintenance phase. Moreover, in the present study, the patients with loss of 17p or TP53 mutation had received only a median of 2 (range, 1–12) or 1 (range, 1–6) DAC courses, while several courses are normally required to achieve best response.

While the clinical observation of the (counter-intuitive) response to HMAs in adverse genetics AML/MDS is more and more accepted within the clinical community, the underlying mechanism of the interaction between hypomethylating activity and these genotypes is still unresolved. Monosomal chromosomal regions may preferentially attract epigenetic silencing [32, 33], providing a particularly sensitive target to DNMT inhibition. Despite the present lack of a conclusive model of this interaction, clinicians need to be aware that the responses, while surprisingly frequent, are often short-lived. Hence, they can also be quite deceptive, by raising unfounded optimism regarding their duration. Thus, patients with adverse genetics who are eligible for allografting should transition to this curative treatment in a timely manner, i.e., before HMA resistance sets in.

In summary, within the specifications of the patient cohort studied, loss of 17p was associated with trends for higher DAC response rates, both within the entire cohort and among patients with CK+ or MK+ AML. Patients with a TP53 mutation achieved similar response rates as patients with wild-type TP53, but had a shorter OS. Our data further support the potential applicability of TP53 aberrations as predictor for HMA treatment, and emphasize a possible role for subclonal mutations in this regard. Isolated TP53 mutation analyses apparently are not sufficient for prediction of HMA response. Cytogenetic analysis remains standard and allows for evaluation of MK+ status and 17p loss. The landscape of HMA-based therapy is changing, and favorable responses in adverse genetics patients are also observed when these drugs are combined with the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax [34] or all-trans retinoic acid [35]. Hence, the impact of the different types of adverse cytogenetics and TP53 alterations (e.g., cytogenetic and molecular genetic mono- or bi-allelic loss) on outcome after HMA combination studies will be of great interest.

References

Jung HA, Maeng CH, Kim M, Kim S, Jung CW, Jang JH (2015) Platelet response during the second cycle of decitabine treatment predicts response and survival for myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Oncotarget 6:16653–16662. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.3914

Metzeler KH, Walker A, Geyer S, Garzon R, Klisovic RB, Bloomfield CD, Blum W, Marcucci G (2012) DNMT3A mutations and response to the hypomethylating agent decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 26:1106–1107. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2011.342

Lübbert M, Rüter BH, Claus R, Schmoor C, Schmid M, Germing U, Kuendgen A, Rethwisch V, Ganser A, Platzbecker U, Galm O, Brugger W, Heil G, Hackanson B, Deschler B, Döhner K, Hagemeijer A, Wijermans PW, Döhner H (2012) A multicenter phase II trial of decitabine as first-line treatment for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia judged unfit for induction chemotherapy. Haematologica 97:393–401. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2011.048231

Wang H, Fan R, Wang X-Q, Wu DP, Lin GW, Xu Y, Li WY (2013) Methylation of Wnt antagonist genes: a useful prognostic marker for myelodysplastic syndrome. Ann Hematol 92:199–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-012-1595-y

Yi L, Sun Y, Levine A (2014) Selected drugs that inhibit DNA methylation can preferentially kill p53 deficient cells. Oncotarget 5:8924–8936. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.2441

Yun H, Damm F, Yap D, Schwarzer A, Chaturvedi A, Jyotsana N, Lübbert M, Bullinger L, Döhner K, Geffers R, Aparicio S, Humphries RK, Ganser A, Heuser M (2014) Impact of MLL5 expression on decitabine efficacy and DNA methylation in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 99:1456–1464. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2013.101386

Bejar R, Lord A, Stevenson K, Bar-Natan M, Pérez-Ladaga A, Zaneveld J, Wang H, Caughey B, Stojanov P, Getz G, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H, Chen R, Stone RM, Neuberg D, Steensma DP, Ebert BL (2014) TET2 mutations predict response to hypomethylating agents in myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Blood 124:2705–2712. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-06-582809

Emadi A, Faramand R, Carter-Cooper B, Tolu S, Ford LA, Lapidus RG, Wetzler M, Wang ES, Etemadi A, Griffiths EA (2015) Presence of isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations may predict clinical response to hypomethylating agents in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol 90:E77–E79. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23965

Lübbert M, Suciu S, Hagemeijer A, Rüter B, Platzbecker U, Giagounidis A, Selleslag D, Labar B, Germing U, Salih HR, Muus P, Pflüger K-H, Schaefer H-E, Bogatyreva L, Aul C, de Witte T, Ganser A, Becker H, Huls G, van der Helm L, Vellenga E, Baron F, Marie J-P, Wijermans PW (2015) Decitabine improves progression-free survival in older high-risk MDS patients with multiple autosomal monosomies: results of a subgroup analysis of the randomized phase III study 06011 of the EORTC Leukemia Cooperative Group and German MDS Study Group. Ann Hematol 95:191–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-015-2547-0

Takahashi K, Patel K, Bueso-Ramos C, Zhang J, Gumbs C, Jabbour E, Kadia T, Andreff M, Konopleva M, DiNardo C, Daver N, Cortes J, Estrov Z, Futreal A, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G (2016) Clinical implications of TP53 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes treated with hypomethylating agents. Oncotarget 7:14172–14187. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.7290

Welch JS, Petti AA, Miller CA, Fronick CC, O’Laughlin M, Fulton RS, Wilson RK, Baty JD, Duncavage EJ, Tandon B, Lee YS, Wartman LD, Uy GL, Ghobadi A, Tomasson MH, Pusic I, Romee R, Fehniger TA, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Vij R, Oh ST, Abboud CN, Cashen AF, Schroeder MA, Jacoby MA, Heath SE, Luber K, Janke MR, Hantel A, Khan N, Sukhanova MJ, Knoebel RW, Stock W, Graubert TA, Walter MJ, Westervelt P, Link DC, DiPersio JF, Ley TJ (2016) TP53and decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med 375:2023–2036. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1605949

van der Helm LH, Berger G, Diepstra A, Huls G, Vellenga E (2017) Overexpression of TP53 is associated with poor survival, but not with reduced response to hypomethylating agents in older patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol 178:810–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14166

Lübbert M, Ihorst G, Sander PN, Bogatyreva L, Becker H, Wijermans PW, Suciu S, Bissé E, Claus R (2017) Elevated fetal haemoglobin is a predictor of better outcome in MDS/AML patients receiving 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine). Br J Haematol 176:609–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14463

Chang C-K, Zhao Y-S, Xu F, Guo J, Zhang Z, He Q, Wu D, Wu LY, Su JY, Song LX, Xiao C, Li X (2016) TP53mutations predict decitabine-induced complete responses in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol 176:600–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14455

Breems DA, Van Putten WLJ, De Greef GE, Van Zelderen-Bhola SL, Gerssen-Schoorl KBJ, Mellink CHM, Nieuwint A, Jotterand M, Hagemeijer A, Beverloo HB, Bob Löwenberg (2008) Monosomal karyotype in acute myeloid leukemia: a better Indicator of poor prognosis than a complex karyotype. JCO 26:4791–4797. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0259

Döhner H, Dolnik A, Tang L, Seymour JF, Minden MD, Stone RM, Bernal del Castillo T, Al-Ali HK, Santini V, Vyas P, Beach CL, MacBeth KJ, Skikne BS, Songer S, Tu N, Bullinger L, Dombret H (2018) Cytogenetics and gene mutations influence survival in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with azacitidine or conventional care. Leukemia 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-018-0257-z

Hiller JK, Schmoor C, Gaidzik VI, Schmidt-Salzmann C, Yalcin A, Abdelkarim M, Blagitko-Dorfs N, Döhner K, Bullinger L, Duyster J, Lübbert M, Hackanson B (2017) Evaluating the impact of genetic and epigenetic aberrations on survival and response in acute myeloid leukemia patients receiving epigenetic therapy. Ann Hematol 96:559–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-016-2912-7

Nieto M, Samper E, Fraga MF, González de Buitrago G, Esteller M, Serrano M (2004) The absence of p53 is critical for the induction of apoptosis by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Oncogene 23:735–743. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1207175

Bally C, Adès L, Renneville A, Sebert M, Eclache V, Preudhomme C, Mozziconacci MJ, de The H, Lehmann-Che J, Fenaux P (2014) Prognostic value of TP53 gene mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia treated with azacitidine. Leuk Res 38:751–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2014.03.012

Nazha A, Kantarjian HM, Bhatt VR, Nogueras-Gonzalez G, Cortes JE, Kadia T, Garcia-Manero G, Abruzzo L, Daver N, Pemmaraju N, Quintas-Cardama A, Ravandi F, Keating M, Borthakur G (2014) Prognostic implications of chromosome 17 abnormalities in the context of monosomal karyotype in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and complex cytogenetics. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia 14:163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2013.07.009

Bernard E, Nannya Y, Hasserjian RP, Devlin SM, Tuechler H, Medina-Martinez JS, Yoshizato T, Shiozawa Y, Saiki R, Malcovati L, Levine MF, Arango JE, Zhou Y, Sole F, Cargo CA, Haase D, Creignou M, Germing U, Zhang Y, Gundem G, Sarian A, van de Loosdrecht AA, Jädersten M, Tobiasson M, Kosmider O, Follo MY, Thol F, Pinheiro RF, Santini V, Kotsianidis I, Boultwood J, Santos FPS, Schanz J, Kasahara S, Ishikawa T, Tsurumi H, Takaori-Kondo A, Kiguchi T, Polprasert C, Bennett JM, Klimek VM, Savona MR, Belickova M, Ganster C, Palomo L, Sanz G, Ades L, Della Porta MG, Smith AG, Werner Y, Patel M, Viale A, Vanness K, Neuberg DS, Stevenson KE, Menghrajani K, Bolton KL, Fenaux P, Pellagatti A, Platzbecker U, Heuser M, Valent P, Chiba S, Miyazaki Y, Finelli C, Voso MT, Shih LY, Fontenay M, Jansen JH, Cervera J, Atsuta Y, Gattermann N, Ebert BL, Bejar R, Greenberg PL, Cazzola M, Hellström-Lindberg E, Ogawa S, Papaemmanuil E (2019) Implications of TP53 allelic state for genome stability, clinical presentation and outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.19.868844

Fenaux P, Preudhomme C, Quiquandon I, Jonveaux P, Laï JL, Vanrumbeke M, Loucheux-Lefebvre MH, Bauters F, Berger R, Kerckaert JP (1992) Mutations of the P53 gene in acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol 80:178–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb08897.x

Haferlach C, Dicker F, Herholz H, Schnittger S, Kern W, Haferlach T (2008) Mutations of the TP53 gene in acute myeloid leukemia are strongly associated with a complex aberrant karyotype. Leukemia 22:1539–1541. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2008.143

Seifert H, Mohr B, Thiede C, Oelschlägel U, Schäkel U, Illmer T, Soucek S, Ehninger G, Schaich M (2009) The prognostic impact of 17p (p53) deletion in 2272 adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 23:656–663. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2008.375

Rücker FG, Schlenk RF, Bullinger L, Kayser S, Teleanu V, Kett H, Habdank M, Kugler CM, Holzmann K, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Held G, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Lübbert M, Fröhling S, Zenz T, Krauter J, Schlegelberger B, Ganser A, Lichter P, Döhner K, Döhner H (2012) TP53 alterations in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype correlate with specific copy number alterations, monosomal karyotype, and dismal outcome. Blood 119:2114–2121. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-08-375758

Strickland SA, Sun Z, Ketterling RP, Cherry AM, Cripe LD, Dewald G, Fernandez HF, Hicks GA, Higgins RR, Lazarus HM, Litzow MR, Luger SM, Paietta EM, Rowe JM, Vance GH, Wiernik P, Wiktor AE, Zhang Y, Tallman MS, ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (2017) Independent prognostic significance of monosomy 17 and impact of karyotype complexity in monosomal karyotype/complex karyotype acute myeloid leukemia: results from four ECOG-ACRIN prospective therapeutic trials. Leuk Res 59:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2017.05.010

Wierzbowska A, Wawrzyniak E, Pluta A, Robak T, Mazur GJ, Dmoszynska A, Cermak J, Oriol A, Lysak D, Arthur C, Doyle M, Xiu L, Ravandi F, Kantarjian HM (2018) Decitabine improves response rate and prolongs progression-free survival in older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and with monosomal karyotype: a subgroup analysis of the DACO-016 trial. Am J Hematol 93:E125–E127. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.25062

Lübbert M, Suciu S, Baila L, Rüter BH, Platzbecker U, Giagounidis A, Selleslag D, Labar B, Germing U, Salih HR, Beeldens F, Muus P, Pflüger KH, Coens C, Hagemeijer A, Eckart Schaefer H, Ganser A, Aul C, de Witte T, Wijermans PW (2011) Low-dose decitabine versus best supportive care in elderly patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: final results of the randomized phase III study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Leukemia Group and the German MDS Study Group. J Clin Oncol 29:1987–1996. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.30.9245

Soenen-Cornu V, Preudhomme C, Laï JL, Zandecki M (1999) del (17p) in myeloid malignancies. Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol 3(4):198-201. https://doi.org/10.4267/2042/37563

Kantarjian HM, Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, Wierzbowska A, Mazur G, Mayer J, Gau JP, Chou WC, Buckstein R, Cermak J, Kuo CY, Oriol A, Ravandi F, Faderl S, Delaunay J, Lysák D, Minden M, Arthur C (2012) Multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial of decitabine versus patient choice, with physician advice, of either supportive care or low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 30:2670–2677. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9429

Becker H, Suciu S, Rüter BH, Platzbecker U, Giagounidis A, Selleslag D, Labar B, Germing U, Salih HR, Muus P, Pflüger KH, Hagemeijer A, Schaefer HE, Fiaccadori V, Baron F, Ganser A, Aul C, de Witte T, Wijermans PW, Lübbert M (2015) Decitabine versus best supportive care in older patients with refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation (RAEBt) - results of a subgroup analysis of the randomized phase III study 06011 of the EORTC Leukemia Cooperative Group and German MDS Study Group (GMDSSG). Ann Hematol 94:2003–2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-015-2489-6

Zhou L, Opalinska J, Sohal D, Yu Y, Mo Y, Bhagat T, Abdel-Wahab O, Fazzari M, Figueroa M, Alencar C, Zhang J, Kambhampati S, Parmar S, Nischal S, Hueck C, Suzuki M, Freidman E, Pellagatti A, Boultwood J, Steidl U, Sauthararajah Y, Yajnik V, Mcmahon C, Gore SD, Platanias LC, Levine R, Melnick A, Wickrema A, Greally JM, Verma A (2011) Aberrant epigenetic and genetic marks are seen in myelodysplastic leukocytes and reveal Dock4 as a candidate pathogenic gene on chromosome 7q. J Biol Chem 286:25211–25223. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.235028

Blum S, Greve G, Lübbert M (2017) Innovative strategies for adverse karyotype acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol 24:89–98. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOH.0000000000000318

DiNardo CD, Pratz K, Pullarkat V, Jonas BA, Arellano M, Becker PS, Frankfurt O, Konopleva M, Wei AH, Kantarjian HM, Xu T, Hong W-J, Chyla B, Potluri J, Pollyea DA, Letai A (2019) Venetoclax combined with decitabine or azacitidine in treatment-naive, elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 133:7–17. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-08-868752

Lübbert M, Grishina O, Schmoor C, Schlenk RF, Jost E, Crysandt M, Heuser M, Thol F, Salih HR, Schittenhelm MM, Germing U, Kuendgen A, Götze KS, Lindemann HW, Müller-Tidow C, Heil G, Scholl S, Bug G, Schwaenen C, Giagounidis A, Neubauer A, Krauter J, Brugger W, de Wit M, Wäsch R, Becker H, May AM, Duyster J, Döhner K, Ganser A, Hackanson B, Döhner H, on behalf of the DECIDER Study Team (2020) Valproate and retinoic acid in combination with decitabine in newly diagnosed elderly non-fit acute myeloid leukemia patients: results of a multicenter, randomized 2x2 phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 38:257–270. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.01053

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Gabriele Greve, Ruhtraut Ziegler, Tobias Ma, Philipp Sander, Christoph Niemöller, and Dennis Zimmer for help during the project.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. The research was supported by the Translational Research Training in Hematology (TRTH) of the European Hematology Association (EHA) and American Society of Hematology (ASH) (to HB), the Berta Ottenstein Fellowship program of the University of Freiburg (to JW), the German Research Foundation [DFG; SPP 1463 ML 429/8-1 (to ML); CRC 992 MEDEP C04 (to ML); FOR 2674 A05 BE 6461/1-1 (to HB), LU 429/16-1 (to ML); FOR 2674 A02 (to HD, KD, LB)], the Böhringer Ingelheim Stiftung [Exploration Grant (to HB)], and the German Cancer Aid [111210 (to HB)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HB: Concept design; data acquisition, analyses, and interpretation; manuscript preparation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. DP: Data acquisition, analyses, and interpretation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. GI: Data acquisition, analyses, and interpretation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. MP: Data analyses and interpretation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. JW: Data analyses and interpretation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. BHR: Treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. LB: Data acquisition, analyses, and interpretation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. BH: Treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; data acquisition, analyses, and interpretation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. UG: Treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. AK: Treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. UP: Treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. KD: Treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; data acquisition, analyses, and interpretation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. AG: Treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. AH: Data acquisition, analyses, and interpretation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. PWW: Treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. HD: Treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. JD: Concept design; data interpretation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. ML: Concept design; treatment of patients and specimen acquisition; data interpretation; manuscript preparation; critical revision and final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of each center. All patients had given written informed consent for collection and use of data and specimens. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee and with the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 448 kb).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Becker, H., Pfeifer, D., Ihorst, G. et al. Monosomal karyotype and chromosome 17p loss or TP53 mutations in decitabine-treated patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol 99, 1551–1560 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-020-04082-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-020-04082-7