Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic had an unprecedented impact on clinical practice and healthcare professionals. We aimed to assess how interventional radiology services (IR services) were impacted by the pandemic and describe adaptations to services and working patterns across the first two waves.

Methods

An anonymous six-part survey created using an online service was distributed as a single-use web link to 7125 members of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe via email. Out of 450 respondents, 327 who completed the survey at least partially including 278 who completed the full survey were included into the analysis.

Results

Interventional radiologists (IRs) reported that the overall workload decreased a lot (18%) or mildly (36%) or remained stable (29%), and research activities were often delayed (30% in most/all projects, 33% in some projects). Extreme concerns about the health of families, patients and general public were reported by 43%, 34% and 40%, respectively, and 29% reported having experienced significant stress (25% quite a bit; 23% somewhat). Compared to the first wave, significant differences were seen regarding changes to working patterns, effect on emergency work, outpatient and day-case services in the second wave. A total of 59% of respondents felt that their organisation was better prepared for a third wave. A total of 19% and 39% reported that the changes implemented would be continued or potentially continued on a long-term basis.

Conclusion

While the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected IR services in terms of workload, research activity and emotional burden, IRs seem to have improved the own perception of adaptation and preparation for further waves of the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

After the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, interventional radiological societies all over the world published many guidelines on how to continue services for urgent procedures while considering cross-contamination and patient, as well as staff safety. Benefitting from the experiences from SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome), temporal and spatial segregation of high-risk patients, use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and segregation of teams were identified as important measures to avert the spread of the virus. Based on key publications, CIRSE has published a checklist for preparing interventional radiology services (IR services) for COVID-19 [1]. Recommendations also suggested the postponement of both non-urgent and elective procedures [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The published literature showed that during the first wave, the overall number of procedures performed by interventional radiologists (IRs) decreased by 16–62%, out-of-clinics hours and stress increased, and the number of outpatient cases was affected [8,9,10,11,12].

Surveys collected in the UK and Canada during the first wave confirmed the reduction in IR services, particularly elective treatments and reported absence of training on the use of PPE [13,14,15]. As the second wave began, further postponement and delays in provisions for IR services were not regarded as a sustainable solution, and many IRs worried about the negative effect on the wellbeing of patients [16,17,18,19].

Our survey aimed to assess how interventional radiology departments across the world adapted in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, we aimed to gain insight into the role of minimally invasive therapies in patient management as well as to assess the workload of IRs in this pandemic. Finally, we attempted to assess which measures could be implemented to facilitate future transitions between standard care and pandemic emergency care.

Methods

Survey Design and Distribution

An anonymous electronic survey (Alchemer LLC, Louisville, USA) was designed to capture the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on workload, service delivery as well as on people and teams. The survey contained 78 questions in total. The study and questionnaire were reviewed and approved by the CIRSE scientific committee. The full questionnaire is available in the supplementary document 1.

The proportion of respondents who completed different parts of the survey is shown in Fig. 1. Three hundred twenty-seven (327) respondents who had completed at least one part were included into the analysis. Two hundred seventy-eight (n = 278, 85.01%) out of all included respondents had completed the whole survey. For the analysis of the differences between the first and second wave, respondents were instructed to compare “March 2020–June 2020” as the first wave to “September 2020 onwards” as the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and only complete responses were considered. The survey was circulated via email to 7125 CIRSE members. To maximise responses, reminders via email and via CIRSE e-newsletters were sent out. Additionally, social media posts on multiple platforms were employed to increase the dissemination of the survey. Data were collected between 17 December 2020 and 8 March 2021.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as counts and percentages of responses for tables and as percentages for figures. Significant differences between categorical variables were assessed using Fisher exact test (p values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant). Data were analysed and plotted using R Studio under R4.0.0.

Results

Demographics

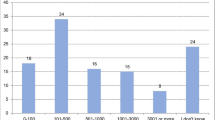

Most (67%) respondents were from Europe or from South and Central America (20%). The majority were employed in tertiary centres (46%), followed by public district general hospitals (23% > 500 beds, 16% < 500 beds) and finally, private hospitals (17%). Forty-three per cent (43%) of respondents were board certified radiologists and 42% had completed interventional radiology training or were specialists in interventional radiology. Eighty-seven per cent (87%) of respondents stated that their department had cared for COVID-19 patients (Table 1).

Impact on Services and Workload

The pandemic was reported to have affected various IR services differently (Fig. 2a). Hepatobiliary, endourology and interventional oncology procedures appeared to be the least affected during the pandemic with 41%, 41% and 45% of the participants, respectively, reporting that they continued offering these services. Peripheral and aortic work and elective embolization procedures such as fibroid or prostate artery embolization were affected more with 20%, 23% and 24% of the participants, respectively, reporting that they continued offering these services. The overall workload generally either decreased (18% a lot, 36% mildly) or remained stable (29%). A total of 18% reported an increase in overall workload (13% mildly increased; 3% increased a lot). When comparing those to responses from IRs who reported no increase, we found significant differences indicating that working hours had been less consolidated, day-case clinics were affected less, and emergency work had increased in volume more (supplementary document 2). As expected, research activity was severely affected with more than 60% of the participants reporting that research projects were either stopped or significantly delayed (Fig. 2b, d).

Multidisciplinary team meetings were either totally (38%) or partly (25%) performed virtually or performed face-to-face with reduction in number of participants (23%) (Fig. 2c).

Burden on IRs

While IRs were generally not concerned about loss of skill or income, IRs reported concerns about the health of families, patients and general public (43%, 34% and 40%, respectively, extremely concerned) (Fig. 3a). Approximately, 30% reported feeling slightly fearful or anxious (Fig. 3b).

Effect on people and team. Violin plots for extent of effect (a, c) or satisfaction (e) on x-axis and areas on y-axis. Percentage of selections for the extent are listed for the respective areas. Heatmap of effect on people with type of effect on the y-axis and extent of effect on x-axis generated using the R heatmap function with no clustering (b). Bar plot indicating percentage of selections of statements (d)

Despite respondents stating that they were supported by their organisations (28% very much; 26% quite a bit; 27% somewhat), many reported high levels of stress (29% very much; 25% quite a bit; 23% somewhat) (Fig. 2c). IRs were completely or generally satisfied with provided PPE (44% and 39%, respectively) and the guidance on PPE (28% and 49%, respectively) (Fig. 3e) with no statistical difference between tertiary centres, public district general hospitals (> 500 beds), public district general hospitals (< 500 beds) and private hospitals (data not shown).

Adaptation of Working Patterns and Patient Care

Adaptations to accommodate patient and staff safety differed between the first wave (March 2020–June 2020) and the second wave (September 2020 onwards) of the pandemic (Fig. 4). Comparisons of the first wave vs the second wave showed that significantly fewer respondents indicated “working from home” (30 vs 23%, p < 0.03), “reducing hours at the hospital” (27 vs 16%. p < 0.009), “reducing operating lists” (42 vs 33%, p < 0.04) and “segregated working teams” (51 vs 23%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4a). Generally, only a small number of IRs reported to have at least partially been redeployed to other departments but we could observe that this number increased for the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (12 vs 35%; data not shown).

Comparing the first wave of the pandemic to the second wave. Changes in working patterns and effect in emergency work and patient care during the first wave and the second wave of the pandemic. Bar plots indicating % of selections of statements for March to June 2020 (left) and September onwards (right) (a–d). Bar plot indicating percentage of selections of statements (e, f). Significant differences between categorical variables were assessed using Fisher exact test (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001)

When asked about how emergency work had been affected, significantly more respondents reported “unchanged” for the second wave (45 vs 27%, p < 0.001), and fewer respondents indicated “decreased” and “significantly decreased” during the second wave of the pandemic (28 vs 43%, p < 0.001 and 4 vs 12% p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 4b). Similarly, regarding outpatient consultations and patient flow through day-case units, more respondents reported “no change to the service” during the second wave (37 vs 18%, p < 0.001 and 38 vs 21%, p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 4c, d). For outpatient clinics, fewer responses for “had to be cancelled” or “had to be done virtually” were given for the second wave (11 vs 29%, p < 0.001 and 16 vs 25%, p < 0.01), and for day-case units, fewer responses were given for “closed part of the time” and “open but received reduced patient numbers” for the second wave (14 vs 24%, p < 0.003 and 32 vs 41%, p < 0.04, respectively). Interestingly, though, the second wave of the pandemic was considered more (38%) or equally intense (29%) compared to the first wave (Fig. 4e). Finally, when asked whether the respondents felt that their organisation was better prepared for a third wave, 59% responded with “yes” and 27% with “somewhat better, but to a small degree” (Fig. 4f).

Post-wave Routines

Following the first wave, 17% and 33% indicated that the services were back to normal or almost back to normal, respectively, 31% reported that services were still affected by the pandemic, and 17% indicated that services had returned to previous activity but were affected again during the second wave (Fig. 5a). Most respondents indicated that cases/referrals were still reduced (48%) and that many/most meetings were still held virtually (48%). A number of IRs reported that the changes that had been implemented during the pandemic would be continued (19%) or potentially continued (39%) on a long-term basis (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

Research from centres all over the world is confirming the disruptive effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare [20,21,22]. The results of our survey showed that there was a general reduction in overall workload, though not all aspects of IR services were affected equally. Hepatobiliary, interventional oncology and endourology procedures did not appear to have been affected as much as endovascular peripheral/aortic procedures and elective embolization. Elective embolization was reported to have stopped completely or almost stopped more often than any other service in question. This illustrates the implementation of the general recommendations to prioritise urgent and oncologic treatments and postpone non-urgent procedures. However, as the second wave followed, it became apparent that long-term adaptations and implementation of routes to provide services safely rather than repeatedly postponing non-urgent care, as well as monitoring the burden on the mental health of IRs and IR service staff, were necessary.

The risk of recurrence and gravity of further waves, combined with mounting pressures secondary to postponed procedures, particularly in the cancer-care setting, has led to worldwide concern and highlighted the need for robust service recovery plans. In survey results from radiologists, 90% of respondents reported reduction in workload and 60% indicated that a workload reduction of over 50% [23]. According to surveys targeting neurosurgery, pancreatic surgery, cardiac surgery or general surgery residents conducted in the first half of 2020, 62–93% of the respondents reported a decrease in cases [24,25,26,27]. In fact, for surgical procedures during the pandemic phases, only emergency and essential-elective surgeries (cancer and transplant surgery) are recommended to be performed. Recommendations suggest postponement of non-urgent cases, or conversion to alternative suitable non-operative/minimally invasive procedures [28,29,30]. As a result, interventional radiology departments are required to be highly adaptive and accommodate this inflow of patients from other medical disciplines. The rigorous discourse of the community might have already enabled initial recovery during the second wave of the pandemic. In order to be able to provide COVID-positive and COVID-negative patients with IR services, structural organisations regarding procedural and transfer logistics were put in place. These included establishing separate routes and rooms for transfer when treating COVID-positive patients, performing bed-side ultrasound-guided procedures and increasing telehealth for outpatient clinics [3, 4, 10, 11, 31,32,33]. Our data captured differences in how the second wave of the pandemic (September 2020 onwards) was handled compared to the first wave (March 2020–June 2020). During the second wave of the pandemic, IRs reported reduction in operating lists and segregation of working teams less frequently despite the fact that COVID-19 patient care was considered more or equally intense. Likewise, less reduction in emergency work, outpatient clinics and day-case units were reported during the second wave of the pandemic.

Interventional radiology appeared to be well-suited to adapt to times of limited resources regarding hospital beds, anaesthesiologists and staff. Minimally invasive procedures such as radioembolisation and ablation can be optimal treatments for local tumour control while requiring shorter hospital stays [34,35,36]. Additionally, the use of local anaesthesia or alternative sedation methods to replace general anaesthesia help reduce the length of hospital stays, which, combined with appropriate pre- and postprocedural medications, often allows for outpatient treatment without always requiring the presence of an anaesthesiologist [37,38,39,40]. The reduced disruption to working patterns, emergency work and day-case/outpatient units showed that IRs could adapt to the requirements of the pandemic. Beyond being able to return to usual procedure volumes, our survey showed that 18% of IRs indicated an increased overall workload with fewer reduction in hours, increased volume of emergency work and less effect on day-case units. This could reflect the increased referrals for IR services in some hospitals.

The initial phases of the pandemic called for increased support and guidance from institutions. Sufficiently available PPE and guidance on the use of PPE were regarded as crucial implementations to ensure staff and patient safety. Especially during the first wave of the pandemic, shortage of PPE was reported, and data were published on dissatisfaction regarding PPE in interventional radiology clinics [3, 14, 15]. Our survey shows that IRs were generally satisfied with the available PPE and PPE guidance, and felt supported by their organisations. Despite that and even with the reduced workload, IRs reported being more stressed and worried about the health of their families and patients, as well as of the general public but not about a potential loss of income or skills. These results could be indicative of increased vulnerability to burnout and anxiety in IRs and other staff as seen in medical personnel of various disciplines [41,42,43,44]. Some IRs have voiced concerns about the effect of the reintroduction of pre-COVID routines and the associated workload resulting from the accumulated postponed procedures [45]. Whether the stress and burden of further waves of the pandemic or the increased workload when returning to normal services will have a strong effect on mental health or whether increased adaptation and familiarisation to the needs of the pandemic will prevent that should be closely monitored by the healthcare authorities of each country.

One limitation of our results is the low return-rate of questionnaires despite reminders and efforts for dissemination of the survey. Due to the extensiveness of the survey and since the invitations to participate were sent out during the most intense period of the second wave, the survey was likely not prioritised relative to patient care and safety. The intrinsic limitation of survey-generated data is the vulnerability to discrepancies between the respondents’ perceptions and the results of quantified data. Especially for the second wave of the pandemic, the apex in intensity and infection rates was experienced at different time points in different regions of the world. Additionally, since the data collection for the survey was stopped in March 2021, some effect regarding mental health or the adaptions of IRs might have not been captured in their entirety.

Conclusion

The results from our survey provide an overview of how the pandemic has affected services and the general workload of IRs. Data indicates that the pandemic resulted in increased stress and concerns but was felt less disruptive during the second wave. Overall, IRs reported to be better prepared for future waves or epidemics. As the pandemic has lasted longer than estimated and is still ongoing, it will be interesting to see how working patterns, workload and mental health will be affected until the end of the pandemic.

References

Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe. COVID-19 resource centre. In: Checklist for preparing your IR service for COVID-19. 2021. https://www.cirse.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CIRSE_APSCVIR_Checklist_COVID19.pdf. Accessed 07 Dec 2021.

Da Zhuang K, Tan BS, Tan BH, et al. Old threat, new enemy: is your interventional radiology service ready for the coronavirus disease 2019? Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2020;43:665–6.

De Gregorio MA, Guirola JA, Magallanes M, et al. COVID-19 outbreak: infection control and management protocol for vascular and interventional radiology departments: consensus document. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2020;43:1208–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-020-02493-7.

Bartal G, Vano E, Paulo G. Get protected! Recommendations for staff in IR. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2021;44:871–6.

Cavenagh T, Katsari S, Kawa B, et al. Role of interventional radiology in line insertion on intensive care during the Covid-19 pandemic. CVIR Endovasc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-020-00171-w.

Too CW, Wen DW, Patel A, et al. Interventional radiology procedures for COVID-19 patients: how we do it. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2020;43:827–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-020-02483-9.

Chandy PE, Nasir MU, Srinivasan S, et al. Interventional radiology and COVID-19: evidence-based measures to limit transmission. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26:236–40. https://doi.org/10.5152/dir.2020.20166.

Zhong J, Datta A, Gordon T, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on interventional radiology services in the UK. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2021;44:134–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-020-02692-2.

Xu Y, Mandal I, Lam S, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on interventional radiology services across the world. Clin Radiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2021.05.001.

Zhu HD, Zeng CH, Lu J, Teng GJ. COVID-19: what should interventional radiologists know and what can they do? J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31:876–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2020.03.022.

Iezzi R, Valente I, Cina A, et al. Longitudinal study of interventional radiology activity in a large metropolitan Italian tertiary care hospital: how the COVID-19 pandemic emergency has changed our activity. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:6940–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-07041-y.

Cahalane AM, Cui J, Sheridan RM, et al. Changes in interventional radiology practice in a tertiary academic center in the United States during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:873–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2020.05.005.

Rostampour S, Cleveland T, White H, et al. Response of UK interventional radiologists to the COVID-19 pandemic: survey findings. CVIR Endovasc. 2020;3:2–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-020-00133-2.

Patel NR, El-Karim GA, Mujoomdar A, et al. Overall impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on interventional radiology services: a Canadian perspective. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0846537120951960.

Marasco G, Nardone OM, Maida M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on clinical practice and training of young gastroenterologists: a European survey. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:1396–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.023.

Veiga J, Amante S, Costa NV, et al. The Covid-19 pandemic constraints may lead to disease progression for patients with liver cancer scheduled to receive locoregional therapies: single-centre retrospective analysis in an interventional radiology unit. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2021;44:669–72.

How GY, Pua U. Trends of interventional radiology procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: the first 27 weeks in the eye of the storm. Insights Imaging. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-020-00938-8.

Katsanos K, Kitrou P, Karnabatidis D. To the editor: interventional radiology in the COVID-19 era: crisis and opportunity. CVIR Endovasc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-020-00162-x.

Denys A, Guiu B, Chevallier P, et al. Interventional oncology at the time of COVID-19 pandemic: problems and solutions. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2020.04.005.

Riera R, Bagattini ÂM, Pacheco RL, et al. Delays and disruptions in cancer health care due to COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1200/go.20.00639.

World Health Organization. News release. In: COVID-19 continues to disrupt essential health services in 90% of countries. 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-04-2021-covid-19-continues-to-disrupt-essential-health-services-in-90-of-countries. Accessed 07 Dec 2021.

World Health Organization. COVID-19: Essential health services. In: Second round of the national pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS-continuity-survey-2021.1. Accessed 07 Dec 2021.

Demirjian NL, Fields BKK, Song C, Reddy S. Impacts of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on healthcare workers: a nationwide survey of United States radiologists. Clin Imaging. 2020;68:218–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.08.027.

Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, et al. A national survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon burnout and career satisfaction among neurosurgery residents. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;80:137–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.08.012.

Aziz H, James T, Remulla D, et al. Effect of COVID-19 on surgical training across the United States: a national survey of general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:431–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.07.037.

Oba A, Stoop TF, Löhr M, et al. Global survey on pancreatic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e87–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004006.

Onorati F, Myers P, Bajona P, et al. Effects of CoVid-19 pandemic on cardiac surgery practice in 61 hospitals worldwide: results of a survey. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;61(6):763–8. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0021-9509.20.11556-8.

Søreide K, Hallet J, Matthews JB, et al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1250–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11670.

De Simone B, Chouillard E, Sartelli M, et al. The management of surgical patients in the emergency setting during COVID-19 pandemic: the WSES position paper. World J Emerg Surg. 2021;16:1–34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-021-00349-0.

Fowler A, Abbott TEF, Pearse RM. Can we safely continue to offer surgical treatments during the COVID-19 pandemic? BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30:268–70. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012544.

Rajakulasingam R, Da Silva EJ, Azzopardi C, et al. Standard operating procedure of image-guided intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic: a combined tertiary musculoskeletal oncology centre experience. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:794.e19-794.e26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2020.07.008.

Ierardi AM, Wood BJ, Gaudino C, et al. How to handle a COVID-19 patient in the angiographic suite. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2020;43:820–6.

Tan BS, Tay KH. Interventional radiology preparedness in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: is there a gold standard? Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2020;43:1420–2.

Helmberger T, Golfieri R, Pech M, et al. Clinical application of trans-arterial radioembolization in hepatic malignancies in Europe: first results from the prospective multicentre observational study CIRSE registry for sir-spheres therapy (CIRT). Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2021;44:21–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-020-02642-y.

Edeline J, Crouzet L, Campillo-Gimenez B, et al. Selective internal radiation therapy compared with sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:635–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-015-3210-7.

Hermida M, Cassinotto C, Piron L, et al. Multimodal percutaneous thermal ablation of small hepatocellular carcinoma: predictive factors of recurrence and survival in western patients. Cancers. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12020313.

Abu Elyazed MM, Abdullah MA. Thoracic paravertebral block for the anesthetic management of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of liver tumors. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2018;34:166–71. https://doi.org/10.4103/joacp.JOACP_39_17.

Cornelis FH, Monard E, Moulin MA, et al. Sedation and analgesia in interventional radiology: where do we stand, where are we heading and why does it matter? Diagn Interv Imaging. 2019;100:753–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2019.10.002.

Ogasawara S, Chiba T, Ooka Y, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of prophylactic dexamethasone for transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Hepatology. 2018;67:575–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29403.

Russell B, Moss C, Rigg A, Van Hemelrijck M. COVID-19 and treatment with NSAIDs and corticosteroids: should we be limiting their use in the clinical setting? Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1–3. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2020.1023.

Foley SJ, O’Loughlin A, Creedon J. Early experiences of radiographers in Ireland during the COVID-19 crisis. Insights Imaging. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-020-00910-6.

Antonijevic J, Binic I, Zikic O, et al. Mental health of medical personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1881.

Buselli R, Corsi M, Baldanzi S, et al. Professional quality of life and mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176180.

Huang HL, Chen RC, Teo I, et al. A survey of anxiety and burnout in the radiology workforce of a tertiary hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2021;65:139–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/1754-9485.13152.

Abadal JM, Gonzalez-Nieto J, Lopez-Zarraga F, et al. Future scenarios and opportunities for interventional radiology in the post COVID-19 era. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2021;27:263–8. https://doi.org/10.5152/dir.2020.20494.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank TERUMO EUROPE NV, Becton Dickinson Austria GmbH and Cook Medical Europe for providing unrestricted grants and the Interventional Radiologists and medical staff who took part in the survey.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from TERUMO EUROPE NV, Becton Dickinson Austria GmbH and Cook Medical Europe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Consent for Publications

All participants had to answer “I agree to participate in this survey and have my responses pooled, analyzed and reported in a scientific publication” and were excluded from participation if they did not agree.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the survey.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomez, F., Reimer, P., Pereira, P.L. et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Interventional Radiology Practice Worldwide: Results from a Global Survey. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 45, 1152–1162 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-022-03090-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-022-03090-6