Abstract

Background

The first and largest peak of trauma mortality is encountered on the trauma site. The aim of this study was to determine whether these trauma-related deaths are preventable. We performed a systematic literature review with a focus on pre-hospital preventable deaths in severely injured patients and their causes.

Methods

Studies published in a peer-reviewed journal between January 1, 1990 and January 10, 2018 were included. Parameters of interest: country of publication, number of patients included, preventable death rate (PP = potentially preventable and DP = definitely preventable), inclusion criteria within studies (pre-hospital only, pre-hospital and hospital deaths), definition of preventability used in each study, type of trauma (blunt versus penetrating), study design (prospective versus retrospective) and causes for preventability mentioned within the study.

Results

After a systematic literature search, 19 papers (total 7235 death) were included in this literature review. The majority (63.1%) of studies used autopsies combined with an expert panel to assess the preventability of death in the patients. Pre-hospital death rates range from 14.6 to 47.6%, in which 4.9–11.3% were definitely preventable and 25.8–42.7% were potentially preventable. The most common (27–58%) reason was a delayed treatment of the trauma victims, followed by management (40–60%) and treatment errors (50–76.6%).

Conclusion

According to our systematic review, a relevant amount of the observed mortality was described as preventable due to delays in treatment and management/treatment errors. Standards in the pre-hospital trauma system and management should be discussed in order to find strategies to reduce mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trauma continues to be a leading cause of death in patients below the age of 40 [1]. According to the WHO’s Global Status Report on Road Safety, more than 1.2 million people die on the world’s roads every year [2]. Large trauma databases document the outcome of severely injured patient. However, the majority of large databases worldwide mainly include patients admitted to a hospital. Studies focused on pre-hospital trauma deaths are rare in comparison with in-hospital observations. One reason for this may lie in difficulty to access the records of patients who died on scene or on the way to the hospital. Moreover, the documentation of these data is often insufficient to answer the research questions concerning the cause of death and the preventability of injuries incurred. In addition, the variability of inclusion criteria and definitions in publications do not allow a clear interpretation of the data. However, the analysis of causes and patterns of pre-hospital deaths is crucial to improve pre-hospital care. Current in-hospital studies describe the patterns of mortality, causes of death in severely injured patients, and they do not confirm the presence of the “trimodal” distribution of trauma deaths reported in previous decades [3, 4]. Several investigations indicate that the temporal distribution of deaths is “unimodal” or “bimodal.” Moreover, autopsy studies revealed that brain injury and severe bleeding are still the leading causes of death in trauma patients [5]. The role of these causes of deaths has not changed over the last three decades and indicates the importance of pre-hospital trauma care and trauma prevention. In this literature review, we aimed to establish the incidence of pre-hospital preventable deaths reported in studies and associated reasons for preventability, such as delay of treatment and errors in management or treatment. Moreover, we aimed to determine the current definition and conventional strategies used to define preventable deaths.

Methods

This systematic review was performed with a focus on publications with data on pre-hospital trauma preventability in severely injured patients. The PubMed/Medline database was screened for relevant publications within the last three decades (1990–2018) in the English and German languages. The following MeSH search terms were used in different combinations: “multiple trauma,” “polytrauma,” preventable deaths,” “pre-hospital deaths,” and “mortality.” Combinations and synonyms were employed for further research. Moreover, we screened references of retrieved publications in order to identify additional papers that may fit the inclusion criteria. The following inclusion criteria for publications were used: original research papers published between January 1, 1990 and January 10, 2018; articles published in peer-reviewed journals of any study design (prospective or retrospective); articles focused on pre-hospital preventable death (studies including only in-hospital data were excluded); textbook chapters, posters and abstracts; and review articles were also excluded. Publications were included if they contained required information (e.g., rate of preventable deaths and reasons for preventability).

Tables summarized the publications in a chronological manner. The following parameters were of interest: country of publication, number of patients included, preventable death rate (PP = potentially preventable and DP = definitely preventable), inclusion criteria (pre-hospital only, pre-hospital and hospital deaths), definition of preventability used in each study, type of trauma (blunt versus penetrating), study design (prospective versus retrospective), and causes for preventability mentioned within the study. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed in order to compare the data.

Results

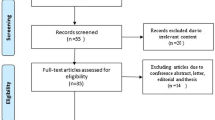

Initially, we have performed a standardized search of literature using above-mentioned MeSH terms and identified a total of 95 publications focusing our topic. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of studies included in the systematic review. Ninety-five papers and abstracts were screened for inclusion criteria of our systematic review. Finally, we identified 40 relevant publications, 21 of which were excluded (17 articles focused on clinical deaths only, and four articles did not include relevant data or were review papers). The remaining 19 articles (7235 death) were included in the present literature review. There were nine reports published between 1990 and 2000, 4 reports published between 2001 and 2010, and 6 articles published between 2011 and 2018.

Table 1 describes the definition for preventability used in the included studies. The majority (12/19, 63.1%) of studies used autopsies in combination with an expert panel to assess the preventability of severe injury in the patients. Six of the nineteen (31.6%) studies used standardized scoring systems as an assessment tool, mostly in combination with other methods. In four (21%) of the studies, only one method was used. Moreover, Table 1 describes studies and their reported preventable death rate. Studies focusing only on pre-hospital trauma death reported preventable death rates from 14.6 to 47.6%. In these studies, 4.9–11.3% were DP and 25.8–42.7% were PP. In publications including both in-hospital and pre-hospital deaths, a wide range of preventable deaths (2–47.6%) were observed. Deaths were determined to be DP at 0.7–26.1% and PP at 3–37%, which corresponds to the wide range noted previously.

Table 2 describes the possible reasons for preventable death found in studies. One of the most frequent (27–58%) reasons was delayed treatment of trauma victims, followed by management errors (40–60%) and treatment errors (50–76.6%). Most frequently, hemorrhagic shock management, fluid therapy, and airway control were identified as sources of treatment errors. Missed injuries were documented in up to 20% of cases.

Discussion

The identification of pre-hospital preventable trauma death is used as an indicator of the efficacy and quality of a given trauma system. Upon reviewing the literature included in this study, we observed that authors used different sources to define preventable deaths. Autopsy was frequently used and is a well-established method to identify pathologic findings and other relevant information. Regardless of the advantages of this method (Table 3), autopsy studies are expensive, time consuming, and therefore not performed routinely. Several authors pointed out the importance of autopsy reports for quality control and assessment of the preventability of trauma deaths [6,7,8,9]. Another assessment tool is the preventable death panel review of deceased patients. The expert panel includes different participants in the trauma chain (e.g., anesthesiologists, emergency department doctors, trauma surgeons, neurosurgeons, radiologist, and nurses). Preventable deaths are identified by a consensus after reviewing autopsy reports, hospital records, pre-hospital information, police notes, or death certificates. Such interdisciplinary panels identify problems and may bring about corrections. However, several publications pointed out a multitude of limitations for this assessment method. Firstly, authors mentioned the importance of the panel’s composition. The lack of organization, interdisciplinarity, training, definitions used, and criteria for judgement may influence the decision in this case review process. Secondly, the value of the review panel has been questioned due to high interrater variability [10, 11]. Finally, it must be noted that an optimal trauma system and ideal circumstances (e.g., weather conditions, etc.) are assumed for these reviews of cases. Therefore, applicability of these data and conclusions may be limited.

The third method used for identification of preventable trauma deaths is the classification of injury severity with the Injury Severity Score (ISS), Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), or use of the Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) measure to determine the probability of survival [12, 13]. These standardized scores are widely used and accepted. However, more and more studies identify a low interrater reliability of ISS and AIS [14, 15]. Moreover, these scores do not include physiological parameters and might therefore be misleading. The TRISS includes physiological parameters such as blood pressure, Glasgow Coma Scale, and age. However, measuring the injury severity with the ISS or AIS comes with the same limitations.

Our systematic review of the literature revealed a wide incidence range of preventable trauma deaths reported in studies. The focus of studies with inclusion of only pre-hospital deaths still showed a high variation between studies, resulting in a rate of preventability from 14.6 to 47.6%. These data represent a relevant number of patients, which could be saved in an ideal trauma system. The large amount of variability between studies is mainly related to several points: Firstly, preventability is a difficult concept to define. Several definitions and modifications exist in the literature [2, 10, 16,17,18,19]. Most of these studies applied a combination of methods (autopsy, panel review, or scores) to identify relevant patients. Secondly, the inclusion of patients (e.g., penetrating versus blunt trauma) in each study showed large differences and variabilities. The discrepancies in study design (prospective versus retrospective) and sample size make the studies less comparable. Thirdly, other factors—such as type of trauma system, level of trauma hospital, country, geographical area or year of the analysis—may have influenced the data. Therefore, the interpretation of changes over the last decade must be performed with caution. Our analysis did not show any relevant changes in the preventability rate over recent years. While numerous studies indicate that the most preventable deaths are attributable to the hospital stay or emergency department, others pointed out that more than 50% of PP death and around 30% of DP death occurred in the pre-hospital phase in the urban trauma setting [9]. Other studies focused on the role of the injury pattern on the preventability rate. Trauma victims without traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) were associated with a higher incidence of PP and DP deaths than patients who had sustained additional brain trauma [20]. Other factors, such as car safety or alarming systems, need to be considered as well. It is still unclear whether the improvement in active or passive car safety influenced the preventable death rate. It is known that passive safety features (e.g., airbags, seat belts, whiplash protection systems, safety rules, etc.) play a role in limiting injuries caused to the drivers, passengers, and pedestrians [21,22,23,24].

The analysis of the reasons for preventable death in trauma patients revealed that delay of treatment was most frequently (27–58%) identified as a leading cause (Table 2). Severe brain injury and exsanguination were described as main causes of death in autopsy studies [5, 25, 26]. Epidemiologic parameters of pre-hospital death did not change over the last decades, according to our findings. Based on prior studies, the incidence of hemorrhagic shock (HS) as the cause of death has decreased within the last decades. Regardless, it is still a leading trauma-related cause of death after TBI. In patients with brain injury, initial airway management, early oxygenation, and resuscitation are crucial to prevent secondary brain damage [27, 28]. Decompression after intracranial bleeding is not possible prior to admission to the hospital. In patients with HS, however, early fluid therapy and bleeding control may reduce the incidence of pre-hospital death [29]. According to prior studies, the majority of avoidable deaths were in patients with treatable brain injuries combined with hypoxia [30]. Clearly, airway and hemorrhage management are key points in the pre-hospital treatment of trauma patients. The reasons for delay of treatment are multifactorial. Of course, one of the most important methods to reduce mortality is the prevention of injuries. Prevention programs—including changes in legislation and public education—have been shown to reduce incidence and mortality in road traffic injuries. Moreover, improvement in automatic systems to alarm car crashes [31, 32] allows early activation of the rescue teams and reduces the pre-hospital time and time to arrival and treatment. Depending on geographical conditions and the organization of the pre-hospital trauma system, rural parts of the country are often at a long distance from a central hospital. Several studies and databases revealed that a helicopter service might lead to a higher number of severely injured patients reaching the hospital alive [33]. The second most frequent cause of preventable trauma death identified in studies is inadequate treatment and management errors (30–81%). The majority of these errors occur after arrival in the ED. Errors in fluid therapy, blood replacement, management of thoracic injuries, and airway control were documented in studies. Standardized approaches to trauma victims (e.g., ATLS Advanced Trauma Life Support/PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support) allow identification of patients at risk to die or to develop secondary injuries or complications. Education on such standardized protocols has been shown to reduce mortality and improve trauma care [34, 35]. Large numbers of medical personnel can be trained in pre-hospital management of trauma patients.

We would like to stress the point to improve the pre-hospital documentation and analysis of data. Large databases in Europe and North America deliver relevant data that allow the identification of risk factors and analysis of various management strategies. However, there is a lack of pre-hospital databases, which could shed light on pre-hospital trauma care. The majority of trauma victims die in the pre-hospital setting, and this needs to gain more attention in trauma research. We would like to encourage research groups to establish pre-hospital databases in order to address the aforementioned issues. New aims in pre-hospital research should be the implementation of databases and improved data collection for these purposes. Finally, another target for future research is the translation of novel pre-hospital interventions. More standardized techniques for pre-hospital diagnostics and hemorrhage control may be useful in the pre-hospital setting. One example is the REBOA (resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta) [36, 37] maneuver, which has been shown to be advantageous in severely bleeding patients. Further studies are needed to show clear indications and associated complications of this device.

Conclusion

The majority of patients die prior to hospital admission. According to our systematic review, a relevant number of patient deaths were preventable. The implementation of pre-hospital alarm systems and discussion of possible improvements and strategies for the pre-hospital trauma system may reduce the delay of treatment in the patients experiencing preventable deaths. Additionally, treatment errors could be reduced by improving education of pre-hospital services and providing standardized management. New pre-hospital interventions and techniques should be considered in order to achieve the aforementioned targets. Finally, we would like to encourage investigators to standardize their assessment techniques and documentation (e.g., implementation of databases) of pre-hospital deceased trauma victims.

References

Ruchholtz S, Lefering R, Paffrath T et al (2008) Reduction in mortality of severely injured patients in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int 105:225–231

WHO (2019) Global status report on road safety. WHO, Geneva

Rauf R, von Matthey F, Croenlein M et al (2019) Changes in the temporal distribution of in-hospital mortality in severely injured patients—an analysis of the TraumaRegister DGU. PLoS ONE 14:e0212095

Trunkey DD, Lim RC (1974) Analysis of 425 consecutive trauma fatalities: an autopsy study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians 3:368–371

Pfeifer R, Schick S, Holzmann C et al (2017) Analysis of injury and mortality patterns in deceased patients with road traffic injuries: an autopsy study. World J Surg 41:3111–3119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4122-4

Papadopoulos IN, Bukis D, Karalas E et al (1996) Preventable prehospital trauma deaths in a Hellenic urban health region: an audit of prehospital trauma care. J Trauma 41:864–869

Hussain LM, Redmond AD (1994) Are pre-hospital deaths from accidental injury preventable? BMJ 308:1077–1080

Davis JS, Satahoo SS, Butler FK et al (2014) An analysis of prehospital deaths: who can we save? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 77:213–218

Kleber C, Giesecke MT, Tsokos M et al (2013) Trauma-related preventable deaths in Berlin 2010: need to change prehospital management strategies and trauma management education. World J Surg 37:1154–1161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1650-9

MacKenzie EJ (1999) Review of evidence regarding trauma system effectiveness resulting from panel studies. J Trauma 47:S34–S41

MacKenzie EJ, Steinwachs DM, Bone LR et al (1992) Inter-rater reliability of preventable death judgments. The Preventable Death Study Group. J Trauma 33:292–302 (discussion 302–293)

Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W et al (1974) The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma 14:187–196

Schluter PJ (2011) The trauma and injury severity score (TRISS) revised. Injury 42:90–96

Ringdal KG, Skaga NO, Hestnes M et al (2013) Abbreviated injury scale: not a reliable basis for summation of injury severity in trauma facilities? Injury 44:691–699

Maduz R, Kugelmeier P, Meili S et al (2017) Major influence of interobserver reliability on polytrauma identification with the injury severity score (ISS): time for a centralised coding in trauma registries? Injury 48:885–889

Chiara O, Cimbanassi S, Pitidis A et al (2006) Preventable trauma deaths: from panel review to population based-studies. World J Emerg Surg 1:12

Shackford SR, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P, McArdle M et al (1987) Assuring quality in a trauma system—the Medical Audit Committee: composition, cost, and results. J Trauma 27:866–875

Rubin HR, Kahn KL, Rubenstein LV et al (1990) Guidelines for structured implicit review of the quality of hospital care for diverse medical and surgical conditions. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA. https://www.rand.org/pubs/notes/N3066.html

Trauma ACoSCo (1990) Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. American College of Surgeons, Chicago

Anderson I, Woodford M, De Dombal F et al (1988) Retrospective study of 1000 deaths from injury in England and Wales. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 296:1305

Burgess AR, Dischinger PC, O’Quinn TD et al (1995) Lower extremity injuries in drivers of airbag-equipped automobiles: clinical and crash reconstruction correlations. J Trauma 38:509–516

Campbell BJ (1987) Safety belt injury reduction related to crash severity and front seated position. J Trauma 27:733–739

Kuner EH, Schlickewei W, Oltmanns D (1996) Injury reduction by the airbag in accidents. Injury 27:185–188

Richter M, Pape HC, Otte D et al (2005) Improvements in passive car safety led to decreased injury severity—a comparison between the 1970s and 1990s. Injury 36:484–488

Pfeifer R, Teuben M, Andruszkow H et al (2016) Mortality patterns in patients with multiple trauma: a systematic review of autopsy studies. PLoS ONE 11:e0148844

Pfeifer R, Tarkin IS, Rocos B et al (2009) Patterns of mortality and causes of death in polytrauma patients—has anything changed? Injury 40:907–911

Lazaridis C, Rusin CG, Robertson CS (2019) Secondary brain injury: predicting and preventing insults. Neuropharmacology 145:145–152

Haddad SH, Arabi YM (2012) Critical care management of severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 20:12

Rossaint R, Bouillon B, Cerny V et al (2016) The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fourth edition. Crit Care 20:100

Chiara O, Scott JD, Cimbanassi S et al (2002) Trauma deaths in an Italian urban area: an audit of pre-hospital and in-hospital trauma care. Injury 33:553–562

Foghel A, Hogeg O, Hogeg M Car accident automatic emergency service alerting system, Google Patents, 2013

Fernandes B, Alam M, Gomes V et al (2016) Automatic accident detection with multi-modal alert system implementation for ITS. Veh Commun 3:1–11

Andruszkow H, Schweigkofler U, Lefering R et al (2016) Impact of helicopter emergency medical service in traumatized patients: which patient benefits most? PLoS ONE 11:e0146897

van Olden GD, Meeuwis JD, Bolhuis HW et al (2004) Advanced trauma life support study: quality of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. J Trauma 57:381–384

van Olden GD, Meeuwis JD, Bolhuis HW et al (2004) Clinical impact of advanced trauma life support. Am J Emerg Med 22:522–525

Jensen KO, Heyard R, Schmitt D et al (2019) Which pre-hospital triage parameters indicate a need for immediate evaluation and treatment of severely injured patients in the resuscitation area? Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 45:91–98

Osborn LA, Brenner ML, Prater SJ et al (2019) Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta: current evidence. Open Access Emerg Med 11:29–38

Thoburn E, Norris P, Flores R et al (1993) System care improves trauma outcome: patient care errors dominate reduced preventable death rate. J Emerg Med 11:135–139

Stocchetti N, Pagliarini G, Gennari M et al (1994) Trauma care in Italy: evidence of in-hospital preventable deaths. J Trauma 36:401–405

Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE et al (1995) Epidemiology of trauma deaths: a reassessment. J Trauma 38:185–193

Sugrue M, Seger M, Sloane D et al (1996) Trauma outcomes: a death analysis study. Ir J Med Sci 165:99–104

Maio RF, Burney RE, Gregor MA et al (1996) A study of preventable trauma mortality in rural Michigan. J Trauma 41:83–90

Limb D, McGowan A, Fairfield JE et al (1996) Prehospital deaths in the Yorkshire Health Region. J Accid Emerg Med 13:248–250

McDermott FT, Cordner SM, Tremayne AB (1997) Management deficiencies and death preventability in 120 Victorian road fatalities (1993–1994). The Consultative Committee on Road Traffic Fatalities in Victoria. Aust N Z J Surg 67:611–618

Henriksson E, Oström M, Eriksson A (2001) Preventability of vehicle-related fatalities. Accid Anal Prev 33:467–475

Zafarghandi MR, Modaghegh MH, Roudsari BS (2003) Preventable trauma death in Tehran: an estimate of trauma care quality in teaching hospitals. J Trauma 55:459–465

Ryan M, Stella J, Chiu H et al (2004) Injury patterns and preventability in prehospital motor vehicle crash fatalities in Victoria. Emerg Med Australas 16:274–279

Falconer JA (2010) Preventability of pre-hospital trauma deaths in southern New Zealand. N Z Med J 123:11–19

Sanddal TL, Esposito TJ, Whitney JR et al (2011) Analysis of preventable trauma deaths and opportunities for trauma care improvement in Utah. J Trauma 70:970–977

Yeboah D, Mock C, Karikari P et al (2014) Minimizing preventable trauma deaths in a limited-resource setting: a test-case of a multidisciplinary panel review approach at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Ghana. World J Surg 38:1707–1712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2452-z

Eyi YE, Toygar M, Karbeyaz K et al (2015) Evaluation of autopsy reports in terms of preventability of traumatic deaths. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 21:127–133

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical statement

This systematic review does not require ethical approval.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pfeifer, R., Halvachizadeh, S., Schick, S. et al. Are Pre-hospital Trauma Deaths Preventable? A Systematic Literature Review. World J Surg 43, 2438–2446 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-05056-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-05056-1