Abstract

Background

Despite the poor prognosis of recurrent esophageal squamous cell cancer (ESCC), long-term survival could be achieved in a subset of patients who successfully underwent surgical resection for recurrence. In this study, we investigated the outcomes of surgical resection for lymph node (LN) or pulmonary (PUL) recurrence in ESCC patients.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the outcomes of ESCC patients who underwent surgical resection between January 2008 and March 2015 for either LN or PUL recurrence after complete response (CR) by chemoradiotherapy or R0 esophagectomy. Every patient fulfilled the original institutional criteria: no recurrence at primary site; recurrence involving in only one organ; expectation of complete resection; and for PUL recurrence, no rapid growth with at least 2 months of observation.

Results

Among the 13 patients analyzed, surgical resection was performed in nine and four patients with LN and PUL recurrence, respectively. R0 resection was achieved in all patients with no fatal surgical complications. Mean duration from the day of the first CR/R0 to the recurrence was 809 (110–2575) days. Median recurrence-free survival following surgical resection for recurrence and overall survival following the first diagnosis of recurrence was 387 and 1297 days, respectively.

Conclusion

Surgical resection for LN or PUL recurrence of ESCC according to our institutional criteria can be performed safely for selected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is a common cancer worldwide causing 400, 200 deaths in 2012 [1]. The prognosis of esophageal cancer has improved dramatically with the advent of multimodal treatment approaches such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical esophagectomy with extensive lymphadenectomy, or chemoradiotherapy (CRT) [2,3,4]. Since definitive CRT is expected to be as effective as radical esophagectomy [4], patients with resectable esophageal cancer may select definitive CRT instead of surgery as the primary treatment. Recurrent esophageal cancer develops in 28–47% of patients who undergo radical esophagectomy [5], and 40% of patients who undergo definitive CRT [6, 7]. The recurrence is frequently observed in lymph nodes, lung, liver, and bone [8]. Mariette et al. [9] reported that 90% of recurrent esophageal cancer cases occurred within 38 months after surgery. Su et al. [8] reported that the time of recurrence, pattern of recurrence, and treatment for recurrence were independent prognostic factors in patients with recurrence after complete resection of esophageal carcinoma.

Currently, no standard treatment is established for the recurrent esophageal cancer with limited metastasis [10]. Therefore, surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and multimodal treatment are considered based on specific criteria of each institution. Although the prognosis of patients with recurrent esophageal cancer is generally poor, long-term survival benefit was reported in a subset of patients who successfully underwent surgical resection for lymph node (LN) or pulmonary (PUL) recurrence [11,12,13,14,15]. In most studies, surgical resection of recurrent LN was performed mainly for cervical lymph nodes (CLNs) [11,12,13]. Surgical resection for abdominal lymph nodes (ALNs) is also considered in some cases, although they frequently involve several lymph nodes, which makes it difficult to perform R0 surgery. As for PUL recurrence, it is the main recurrence pattern of hematogenous way, with a frequency of 17.5–41.4% after radical esophagectomy [15]. Although PUL recurrence is often detected as multiple lesions or in combination with extrapulmonary metastasis, surgical resection was reported to be effective in several patients with limited recurrent PUL lesions that were determined to be resectable [15, 16].

Clinical significance of surgical resection in esophageal cancer patients with limited LN or PUL recurrence has not been studied enough. We hypothesized that surgical resection for LN or PUL limited recurrence in esophageal cancer patients is effective if patients are selected based on appropriate indication. The aim of this study was to investigate the clinicopathological characteristics and the prognosis of patients who underwent surgical intervention for recurrent esophageal cancer and to propose the indications for surgical resection for those patients.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of consecutive esophageal squamous cell cancer (ESCC) patients who underwent surgical resection between January 2008 and March 2015 for either LN or PUL recurrence as the first treatment after complete response (CR) by CRT, or R0 esophagectomy at Shizuoka Cancer Center, Shizuoka, Japan. As for CRT for patients with stage II or higher stage, we routinely performed two cycles of additional chemotherapy following concurrent CRT. The standard definitive CRT regimen was consisted either of the followings: (1) 700 mg/m2 of 5-fluorouracil on days 1 through 4 and days 29 through 33, and 70 mg/m2 of cisplatin on day 1 and 29 with radiation dose of 60 gray in 2 gray fractions; (2) 1000 mg/m2 of 5-fluorouracil on days 1 through 4 and days 29 through 33, and 75 mg/m2 of cisplatin on day 1 and 29 with radiation dose of 50.4 gray in 1.8 gray fractions. If patients were diagnosed as not CR, we performed salvage surgery. Patients were followed up every 6 months by computed tomography for 5 years after the treatment. We defined CR for patients who received CRT when we confirmed all the target and nontarget lesions disappear, which include complete response of primary lesion on endoscopy according to the Japanese classification of esophageal cancer [17].

Patients fulfilled the following institutional criteria based on the classical Thomford criteria [18]: no recurrence at primary site; recurrence involving in only one organ; expectation of complete resection; and for PUL recurrence, no rapid growth with at least 2 months of observation. We apply metastasectomy only to cervical and abdominal LN, or PUL regarding guidelines and previous reports [10]. The indication for surgical resection in each case was discussed at a multidisciplinary cancer board.

This study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committee of Shizuoka Cancer Center.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and parameters were compared using the log-rank test. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the day of first recurrence to death due to any cause or to the last follow-up, and recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from the day of surgical resection for recurrence to the day of the second recurrence. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

From January 2008 to March 2015, we had 600 esophageal cancer patients in total. A total of 231 patients underwent surgery, and 369 patients underwent CRT. The flowchart of the patients during this study period is shown in Fig. 1. There were nine other patients who had primary definitive treatment before 2008 and recurred in this study period. We included these patients into this study. There were 31 patients in total who had LN or PUL recurrence which fulfilled our institutional criteria during the study period. Of these, 15 patients underwent surgical resection for either LN or PUL recurrence of ESCC and the rest of the patients underwent chemotherapy or CRT. Among 15 patients who underwent surgical resection, two patients who had previous treatment other than surgical resection for recurrence were excluded; thus, a total of 13 patients were analyzed in this study. Also in the same study period, there were 16 patients who satisfied our institutional criteria and chose non-surgical treatment for LN or PUL recurrence. Patient characteristics of both those who chose surgical resection and non-surgical treatment are shown in Table 1.

In patients who underwent surgical resection for the recurrence, the primary definitive treatment was CRT in 12 patients, and two of them underwent salvage surgery following CRT. One patient had only surgery as the primary definitive treatment (Table 1). The sites of recurrence were CLNs or ALNs in nine patients who had only undergone CRT, and PUL in two patients who had had salvage surgery following CRT, and PUL in one patient who had had R0 surgery alone. The details of the metastatic region among a total of nine patients with LN recurrence were: supraclavicular LN in one patient; deep CLN in one patient; cervical paraesophageal LN in one patient; left recurrent laryngeal nerve LN in two patients; right paracardial LN in two patients; lesser curvature LN along the branches of the left gastric artery or the second branch and distal part of the right gastric artery in one patient; and LN along the root of the left gastric artery in one patient. Two patients had metastases in more than one LN within the same region. The recurrent LNs existed in the irradiation field except one patient who had right paracardial LN recurrence. In our study, there were four patients with tumor located in upper thoracic or cervical (Ut/Ce) esophagus, and nine patients with tumor located in middle thoracic or lower thoracic (Mt/Lt) esophagus. In patients with Ut/Ce located tumor, the recurrence was seen in CLN in three patients and PUL in one patient. In patients with Mt/Lt located tumor, the recurrence was seen in CLN in two patients, ALN in four patients, and PUL in three patients. Median time from CR/R0 by the primary treatment to the diagnosis of recurrence was 809 (110–2575) days, and the median duration from the diagnosis of recurrence to the resection was 45 (25–69) and 189 (90–382) days in patients with LN and PUL recurrence, respectively.

Among four patients with PUL recurrence, wedge pulmonary resection was performed in three patients, and one patient underwent pulmonary lobectomy. In patients with CLN or ALN recurrence, dissection of the involved LN was performed. All patients underwent R0 surgery, and none of the patients received adjuvant therapy. Grade II or higher surgical complications according to the Clavien–Dindo classification was observed in two patients: grade IIIa empyema in one patient who underwent pulmonary resection, and grade II surgical site infection in patient who underwent CLN dissection. There were no fatal complications or in-hospital deaths.

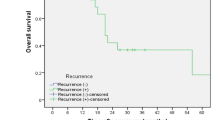

Among all patients, the median RFS was 387 days, and the median OS was 1297 days (Figs. 2, 3). The median OS in patients with PUL recurrence and LN recurrence was 1119 days and not reached, respectively (p = 0.896) (Fig. 4).

Among all patients included in the study, four patients (31%) had no recurrence after the surgery, whereas two patients died of the other disease (leukemia in one patient, and cerebral infarction in another). The remaining seven patients had a second recurrence. The recurrent lesions were LNs in six patients, and pulmonary recurrence in one patient. All six patients with second recurrence in LNs underwent palliative chemotherapy. The one patient with pulmonary recurrence underwent surgery again.

We also compared the OS of the 13 patients with that of 16 patients who chose non-surgical treatment during the same study period for LN or PUL recurrence which we considered resectable based on our institutional criteria. We found no significant difference in LN recurrence group (Fig. 5a) nor PUL recurrence group (Fig. 5b).

Discussion

Optimal treatment for LN or PUL limited recurrence in esophageal cancer patients remains uncertain; therefore, the treatments vary across institutions and are decided on a case-by-case basis according to the site and pattern of recurrence. Based on the specific criteria used as indications of surgery at our institution, R0 resection was performed safely in all patients with no severe complications.

Several studies reported that a number of factors including the interval between esophageal resection and recurrence, the type of recurrence, the treatment after recurrence, and the primary location of the tumor were prognostic factors in patients with recurrent disease [6,7,8]. It has been reported that the mean survival period in recurrent esophageal cancer patients with distant metastasis including PUL recurrence is 9 months, and that of LN recurrence is 7 months [19]. In the present study, the mean survival period was 668 days (22 months), which may suggest that the surgical resection for LN or PUL recurrence is an appropriate treatment option. The survival of the patients who underwent surgical resection of nodal recurrence after definitive treatment was better than those in the previous results reported by Yuan et al. [20]. In previous study, patients who underwent esophagectomy as the primary definitive treatment are evaluated mainly. The difference of patients group may affect the results of survivals of the patients with recurrent esophageal cancer. In our study, we only included patients who satisfied our institutional criteria, by which we strictly selected the patients for surgical treatment regardless of the previous treatment. This patient selection could be the difference in survivals of patients who underwent surgical resection between previous study and ours.

The mean duration from the diagnosis of recurrence to the surgical resection was longer in patients with PUL recurrence than in those with CLN or ALN recurrence. In our institution, we usually plan follow-up with computed tomography for PUL recurrence in the short duration within 2 or 3 months after the initial diagnosis, to confirm the absence of new lesions and to prevent early relapse at another site after the resection. Otherwise, pulmonary resection is planned if complete resection for PUL lesion is still considered to be feasible. Although the prognosis of metastasectomy for hematogenous metastasis, such as liver, is reported to be bad [21], pulmonary resection for PUL recurrence has been suggested to lead better prognosis. Therefore, we only included PUL recurrence into this study. As for lymph node recurrence, since it is not considered to be directly related to systemic metastasis, we usually perform surgery without taking additional time before the surgery.

There was heterogeneity in the recurrent pattern according to previous treatment. We found almost all patients (nine of ten patients) who had CRT revealed to have LN recurrence. On the other hand, three patients who had R0 surgery as the definitive treatment revealed to have PUL recurrence.

In our study, all patients had R0 resection for recurrent lesion and did not receive adjuvant treatment after surgery. In some studies, patients who received adjuvant therapy after surgical resection for recurrence achieved long-term survival [11, 13]; however, evidence demonstrating the utility of adjuvant therapy in these patients remains insufficient. Despite the small number of patients, the OS of patients in our study was longer than that previously reported in patients who did receive adjuvant therapy. It suggests that adjuvant therapy may not be necessary in all cases. The significance of adjuvant therapy for resected recurrent esophageal cancer should be investigated in future studies.

One major strength of the present study was that indication of surgical resection for the recurrence was determined according to predefined institutional criteria in all cases. Although the results showed favorable outcome, there are several limitations in this study. First, as this was a single-center retrospective analysis, the number of patients included was too small to evaluate statistically and reach definitive conclusions. However, we might suggest the safety of surgical choice for PUL recurrent patients. For example, history of CRT may increase morbidity associated with pulmonary resection. Among four patients with PUL recurrence in our study, most of them (three of four) had CRT as the previous treatment, and only one patient had surgery without CRT. We could not evaluate the impact of previous treatment on pulmonary resection, but we could show the safety of the resection after CRT at least. According to guidelines for diagnoses and treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus, the treatment for recurrence after definitive treatment may differ according to the previous treatment [10]. The standard strategy for recurrent esophageal cancer is not yet defined regardless of the type of previous treatment. Our study is focused on surgical treatment for recurrent esophageal cancer, and we consider surgical treatment can be the choice for both patients who had chemoradiotherapy and surgical treatment previously. Therefore, we did not distinguish patients based on previous treatment. Second, patients with LN or PUL metastasis might have favorable prognosis only with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Actually, we showed there was no significant difference in OS according to the treatment selected for LN or PUL recurrence. Still, we believe that surgical resection can be a hopeful treatment option for LN or PUL recurrence which fulfills our institutional criteria. In contrast to chemotherapy, a benefit of surgical resection is that patients could be free from any treatment. In the present study, half of the patients did not experience a second recurrence after surgery. Third, in some cases with PUL recurrence, surgical resection was undergone as biopsy because PUL recurrence of esophageal cancer could not be distinguished from primary pulmonary cancer. Although there was paucity of evidence that supported surgical resection for PUL recurrence of esophageal cancer, these results from a chance help to validate our criteria for resection.

In conclusion, surgical resection in patients with either LN or PUL recurrence could be performed safely in accordance with our institutional criteria that included no recurrence at primary site; recurrence involving only one organ; expectation of complete resection; and no rapid growth. Especially for PUL recurrence, even patients who had history of CRT would safely have surgical resection if selected appropriately by our institutional criteria. Although further prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings, our institutional criteria were appropriate when we consider surgical resection for LN or PUL recurrence of ESCC following curative treatment.

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL et al (2015) Global cancer statistics 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65(2):87–108

Ando N, Kato H, Igaki H et al (2012) A randomized trial comparing postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil versus preoperative chemotherapy for localized advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus (JCOG9907). Ann Surg Oncol 19:68–74

Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM et al (2011) Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 12:681–692

Bedenne L, Michel P, Bouche O et al (2007) Chemoradiation followed by surgery compared with chemoradiation alone in squamous cancer of the esophagus: FFCD 9102. J Clin Oncol 25:1160–1168

Nieman DR, Peters JH (2013) Treatment strategies for esophageal cancer. Gastroenterol Clin N Am 42(3):187–197

Toh Y (2010) Follow-up and recurrence after a curative esophagectomy for patients with esophageal cancer: the first indicators for recurrence and their prognostic values. Esophagus 7(1):37–43

Ishihara R, Yamamoto S, Iishi H et al (2010) Factors predictive of tumor recurrence and survival after initial complete response of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma to definitive chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 76(1):123–129

Su XD, Zhang DK, Zhang X et al (2014) Prognostic factors in patients with recurrence after complete resection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Dis 6(7):949–957

Mariette C, Balon JM, Piessen G et al (2003) Pattern of recurrence following complete resection of esophageal carcinoma and factors predictive of recurrent disease. Cancer 97:1616–1623

The Japan Esophageal Society (2017) Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus 2017 edition. Kanehara-shuppan

Nakamura T, Ota M, Narumiya K et al (2008) Multimodal treatment for lymph node recurrence of esophageal carcinoma after curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol 15(9):2451–2457

Yano M, Takachi Y, Doki Y et al (2006) Prognosis of patients who develop cervical lymph node recurrence following curative resection for thoracic esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus 19:73–77

Motoyama S, Kitamura M, Saito R et al (2006) Outcome and treatment strategy for mid-and lower-thoracic esophageal cancer recurring locally in the lymph nodes of the neck. World J Surg 30:191–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0092-z

Kozu Y, Sato H, Tsubosa Y et al (2011) Surgical treatment for pulmonary metastases from esophageal carcinoma after definitive chemoradiotherapy: experience from a single institution. J Cardiothorac Surg 6:135

Ichikawa H, Kosugi S, Nakagawa S et al (2011) Operative treatment for metachronous pulmonary metastasis from esophageal carcinoma. Surgery 149:164–170

Chen F, Sato K, Sakai H et al (2008) Pulmonary resection for metastasis from esophageal carcinoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 7:809–812

Japanese Esophageal Society (2017) Japanese classification of esophageal cancer, 11 edition: part II and III. Esophagus 14:37–65

Thomford NR, Woolner LB, Clagett OT (1965) The surgical treatment of metastatic tumors in the lungs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 49:357–363

Bhansali M, Fujita H, Kakegawa T et al (1997) Pattern of recurrence after extended radical esophagectomy with three-field lymph node dissection for squamous cell carcinoma in the thoracic esophagus. World J Surg 21:275–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002689900228

Yuan X, Lv J, Dong H et al (2017) Does cervical lymph node recurrence after oesophagectomy or definitive chemoradiotherapy for thoracic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma benefit from salvage treatment? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 24:792–795

Nakagawa S, Kanda T, Kosugi S et al (2004) Recurrence patterns of squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus after extended radical esophagectomy with three-field lymphadenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 198:205–211

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Shimada, A., Tsushima, T., Tsubosa, Y. et al. Validity of Surgical Resection for Lymph Node or Pulmonary Recurrence of Esophageal Cancer After Definitive Treatment. World J Surg 43, 1286–1293 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-04904-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-04904-w