Abstract

Background

Changing work practices make it imperative that surgery selects candidates for training who demonstrate the spectrum of abilities that best facilitate learning and development of attributes that, by the end of their training, approximate the characteristics of a consultant surgeon.

Aims

The aim of our study was to determine the relative merits of components of a program used for competitive selection of trainees into higher surgical training (HST) in general surgery.

Methods

Applicants (N = 98, males 69, mean age 31 years [range 29–40]) to the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland program for HST in general surgery between 2006 and 2008 were assessed. Clinical, basic surgical training, logbook, research performance, and reference scores were evaluated. A total of 51 candidates were shortlisted and completed a further objective assessment of their technical skills and interview performances.

Results

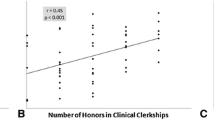

Shortlisted candidates performed better (p < 0.003) on all assessed parameters. Compared with candidates who were not selected for HST, those who were selected (N = 31) significantly outperformed on individual assessments and overall (p < 0.0001). Logistic regression analysis showed that clinical, technical skills, and research assessments, but not interview, predicted (92.2 %) HST selection outcomes.

Conclusions

Candidates selected for the national HST program in Ireland consistently outperformed those who were not. The assessments reliably and consistently distinguished between candidates, and all of the assessed parameters (except interview) contributed to a highly predictive selection model. This is the largest reported dataset from an objective, transparent, and fair assessment program for selection of the next generation of surgeons.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gallagher AG, O’Sullivan GC (2011) Fundamentals of surgical simulation: principles and practices. Springer, London

Bell RH Jr, Biester TW, Tabuenca A et al (2009) Operative experience of residents in US general surgery programs: a gap between expectation and experience. Ann Surg 249:719–724

Pellegrini CA (2006) Surgical education in the United States: navigating the white waters. Ann Surg 244:335–342

Darzi A, Smith S, Taffinder N (1999) Assessing operative skill. Needs to become more objective. BMJ 318(7188):887–888

Beall DP (1999) The ACGME institutional requirements: what residents need to know. JAMA 281:2352

Pickersgill T (2001) The European working time directive for doctors in training. BMJ 323:1266

Bulstrode C, Pearson C, Hunt V (1998) Appointing doctors. Skills Unit Oxford, Oxford

Rubin P (2007) Postgraduate medical education and training board (PMETB). Lancet 369:1341

Morris PJ (2003) Postgraduate medical education and training board (PMETB). Bull R Coll Surg Engl 85(5):148–151

Cuschieri A (1995) Whither minimal access surgery: tribulations and expectations. Am J Surg 169:9–19

Gallagher AG, Smith CD, Bowers SP et al (2003) Psychomotor skills assessment in practicing surgeons experienced in performing advanced laparoscopic procedures. J Am Coll Surg 197:479–488

Chipman JG, Schmitz CC (2009) Using objective structured assessment of technical skills to evaluate a basic skills simulation curriculum for first-year surgical residents. J Am Coll Surg 209(364–370):e362

Derossis AM, Antoniuk M, Fried GM (1999) Evaluation of laparoscopic skills: a 2-year follow-up during residency training. Can J Surg 42:293–296

Gallagher AG, Lederman AB, McGlade K et al (2004) Discriminative validity of the minimally invasive surgical trainer in virtual reality (MIST-VR) using criteria levels based on expert performance. Surg Endosc 18:660–665

Peters JH, Fried GM, Swanstrom LL et al (2004) Development and validation of a comprehensive program of education and assessment of the basic fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery. Surgery 135:21–27

Gallagher AG, Neary P, Gillen P et al (2008) Novel method for assessment and selection of trainees for higher surgical training in general surgery. Aust N Z J Surg 78:282–290

Carroll SM, Kennedy AM, Traynor O et al (2009) Objective assessment of surgical performance and its impact on a national selection programme of candidates for higher surgical training in plastic surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 62:1543–1549

Gallagher AG, Ritter EM, Satava RM (2003) Fundamental principles of validation, and reliability: rigorous science for the assessment of surgical education and training. Surg Endosc 17:1525–1529

Irish Surgical Postgraduate Training Committee (2011). Standardised selection process for higher surgical training: guide to the marking system (B). Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland

Halsted WS (1904) The training of the surgeon. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp xv:267–275

Cameron JL (1997) William Stewart Halsted: our surgical heritage. Ann Surg 225:445–458

Martin JA, Regehr G, Reznick R et al (1997) Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. Br J Surg 84:273–278

Gallagher AG, Satava RM (2002) Virtual reality as a metric for the assessment of laparoscopic psychomotor skills: learning curves and reliability measures. Surg Endosc 16:1746–1752

Beard JB, Marriott J, Purdie H et al (2011) Assessing the surgical skills of trainees in the operating theatre: a prospective observational study of the methodology. Health Technol Assess 15:1–162

Räder SB, Jørgensen E, Bech B et al (2011) Use of performance curves in estimating number of procedures required to achieve proficiency in coronary angiography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 78:387–393

McPhee J, Wr Robinson, Eslami M et al (2011) Surgeon case volume, not institution case volume, is the primary determinant of in-hospital mortality after elective open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 53:591–599

Nallamothu BK, Gurm HS, Ting HH et al (2011) Operator experience and carotid stenting outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA 306:1338–1343

McClusky DA 3rd, Ritter EM, Lederman AB et al (2005) Correlation between perceptual, visuo-spatial, and psychomotor aptitude to duration of training required to reach performance goals on the MIST-VR surgical simulator. Am Surg 71:13–20 (discussion 20–11)

Ritter EM, McClusky DA 3rd, Gallagher AG et al (2006) Perceptual, visuospatial, and psychomotor abilities correlate with duration of training required on a virtual-reality flexible endoscopy simulator. Am J Surg 192:379–384

Conway JM, Jako RA, Goodman DF (1995) A meta-analysis of interrater and internal consistency reliability of selection interviews. J Appl Psychol 80:565–579

Latham GP, Saari LM, Pursell ED et al (1980) The situational interview. J Appl Psychol 65:422–442

Crawford ME (2005) Commentary: reassuring evidence on competency based selection. BMJ 330:714

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallagher, A.G., O’Sullivan, G.C., Neary, P.C. et al. An Objective Evaluation of a Multi-Component, Competitive, Selection Process for Admitting Surgeons into Higher Surgical Training in a National Setting. World J Surg 38, 296–304 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2302-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2302-4