Abstract

Purpose

Arterial inflammation and vascular calcification are regarded as early prognostic markers of cardiovascular disease (CVD). In this study we investigated the relationship between CVD risk and arterial inflammation (18F-FDG PET/CT imaging), vascular calcification metabolism (Na18F PET/CT imaging), and vascular calcium burden (CT imaging) of the thoracic aorta in a population at low CVD risk.

Methods

Study participants underwent blood pressure measurements, blood analyses, and 18F-FDG and Na18F PET/CT imaging. In addition, the 10-year risk for development of CVD, based on the Framingham risk score (FRS), was estimated. CVD risk was compared across quartiles of thoracic aorta 18F-FDG uptake, Na18F uptake, and calcium burden on CT.

Results

A total of 139 subjects (52 % men, mean age 49 years, age range 21 – 75 years, median FRS 6 %) were evaluated. CVD risk was, on average, 3.7 times higher among subjects with thoracic aorta Na18F uptake in the highest quartile compared with those in the lowest quartile of the distribution (15.5 % vs. 4.2 %; P < 0.001). CVD risk was on average, 3.7 times higher among subjects with a thoracic aorta calcium burden on CT in the highest quartile compared with those in the lowest two quartiles of the distribution (18.0 % vs. 4.9 %; P < 0.001). CVD risk was similar in subjects in all quartiles of thoracic aorta 18F-FDG uptake.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that an unfavourable CVD risk profile is associated with marked increases in vascular calcification metabolism and vascular calcium burden of the thoracic aorta, but not with arterial inflammation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adverse cardiovascular events and their sequelae are a major health concern in Western societies [1]. Efforts to prevent adverse cardiovascular events have focused on identifying asymptomatic individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), the so-called “vulnerable” patient [2, 3]. In theory, vulnerable patients benefit most from intensive evidence-based medical interventions. However, identifying the vulnerable patient remains a major ongoing challenge [2].

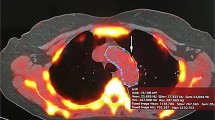

Recent developments in cardiovascular imaging, aimed at visualizing key pathophysiological processes in CVD, offer new opportunities for assessing patient vulnerability. Amongst others, arterial inflammation [4] and vascular calcification [5] have received attention as potent markers of increased CVD risk [6–8]. 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging can noninvasively assess arterial inflammation, whereas Na18F PET/CT and CT imaging can noninvasively assess vascular calcification (Fig. 1).

Axial CT (a, c), 18F-FDG PET/CT (b), and Na18F PET/CT (d) images obtained at the same location in 69-year-old man with hypertension, a body mass index of 28 kg/m2, and a Framingham risk score of 26 %. 18F-FDG accumulation is seen in the descending thoracic aorta (b white arrowheads), but not at sites with structural calcium deposits (a, c black arrowheads). In the Na18F PET/CT image (d) active (white arrowhead) and indolent (black arrowhead) vascular calcifications are distinguished

Although CVD risk in relation to arterial inflammation (18F-FDG PET/CT imaging), vascular calcification metabolism (Na18F PET/CT imaging), and vascular calcium burden (CT imaging) has been previously studied, in only a limited number of studies a combined approach has been applied [9, 10]. Moreover, few investigations have evaluated these cardiovascular imaging modalities in relation to CVD risk in a population at low CVD risk. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between CVD risk and arterial inflammation, vascular calcification metabolism, and vascular calcium burden in a cohort of subjects at low CVD risk, namely healthy volunteers and patients evaluated for chest pain syndromes.

Materials and methods

This study was part of the “Cardiovascular Molecular Calcification Assessed by 18F-NaF PET/CT” (CAMONA) study. The CAMONA study was approved by the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics, registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01724749), and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Subject selection

We recruited a heterogeneous population of subjects, including healthy volunteers and patients evaluated for chest pain syndromes. This allowed us to study the relationship between CVD risk and arterial inflammation, vascular calcification metabolism, and vascular calcium burden in a heterogeneous, but clinically relevant, group of subjects regarded to be at low CVD risk. Healthy volunteers were recruited from the general population by local advertisement or from the blood bank of Odense University Hospital, Denmark. Volunteers free of oncological disease, autoimmune disease, immunodeficiency syndromes, alcohol abuse, illicit drug use, (symptoms suggesting) CVD, or any prescription medication were considered healthy and were eligible for inclusion. Patients evaluated for chest pain syndromes were recruited from those referred for coronary CT angiography. Only patients with a 10-year risk of fatal CVD equal to or above 1 %, as estimated by the body mass index based the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation tool [11], were eligible for inclusion. Pregnant women were not considered for inclusion.

Study design

Study participants were evaluated by questionnaires, blood pressure measurements, blood analyses, the Framingham risk score (FRS) [12], 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging, and Na18F PET/CT imaging. In addition, body weight and body mass index were determined. Questionnaires collected information about smoking habits, family history of CVD, and prescription medication. Blood pressure was measured three times after the subject had rested for of at least 30 min in the supine position. The average of the last two measurements was taken as the systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Blood analyses included fasting serum total cholesterol, serum LDL cholesterol, serum HDL cholesterol, serum triglycerides, fasting plasma glucose and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), and the Modification of Diet and Renal Disease (MDRD) equation was used to estimate glomerular filtration rate. In each subject, the 10-year risk of developing CVD was estimated using the FRS (i.e. risk of coronary death, myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, angina, ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, peripheral artery disease, heart failure) based on age, gender, systolic blood pressure, total serum cholesterol, serum HDL cholesterol, smoking habit, and treatment for hypertension [12].

18F-FDG and Na18F PET/CT imaging were performed according to previously published methods [13, 14]. In summary, 18F-FDG and Na18F PET/CT imaging were performed on hybrid PET/CT systems (GE Discovery STE, VCT, RX, and 690/710 systems). Subjects were randomly allocated to a PET/CT system by the department’s booking system. PET/CT system specifications and image reconstruction parameters are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging was performed 180 min after intravenous injection of 4.0 MBq of 18F-FDG per kilogram of body weight [13]. 18F-FDG was administered after an overnight fast of at least 8 h. Before 18F-FDG injection, the blood glucose concentration was determined to ensure a value below 8 mmol/L. On average, Na18F PET/CT imaging was performed within 2 weeks of 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. Na18F PET/CT imaging was performed 90 min after intravenous injection of 2.2 MBq of Na18F per kilogram of body weight [14]. PET images were corrected for attenuation, scatter, random coincidences, and scanner dead time. Low–dose CT imaging (140 kV, 30 – 110 mA, noise index 25, 0.8 s per rotation, slice thickness 3.75 mm) was performed for attenuation correction, for anatomical orientation, and to determine the thoracic aorta CT calcium burden. The effective radiation dose received from the entire imaging protocol was approximately 14 mSv.

Quantitative image analyses

All images were analysed using Philips IntelliSpace Portal Client, version 4.0. The image analyst was masked to the subject’s demographics and to the image specifications. Arterial 18F-FDG and Na18F uptake were quantified according to previously published methods [13–15]. In summary, uptake of 18F-FDG in the thoracic aorta was determined by manually placing an oval region of interest (ROI) around the outer perimeter of the artery on every slice of the axially oriented PET/CT images. For each ROI, the maximum decay-corrected 18F-FDG activity concentration was calculated. The maximum values obtained for each ROI were summed and divided by the number of ROIs, resulting in a single averaged maximum value (FDGMAX). Thoracic aorta NaFMAX values were calculated in a similar manner. Blood 18F-FDG activity and blood Na18F activity were determined by drawing a single ROI in the lumen of the superior vena cava. Blood 18F-FDG activity and blood Na18F activity were quantified as the decay-corrected mean radiotracer activity concentration. Finally, the thoracic aorta CT calcium burden was calculated.

The CT calcium burden was determined on low-dose CT images obtained as part of PET/CT imaging by calculating the calcium volume on every slice of the axially oriented CT images. Volumes obtained in each slice were summed and divided by the number of slices, resulting in a single mean CT calcium volume. The detection threshold for vascular calcium was set at 130 HU. The agreement between mean calcium volumes calculated on CT images from 18F-FDG PET/CT and those calculated from Na18F PET/CT was found to be excellent, and the CT images from 18F-FDG PET/CT were therefore used as reference for the statistical analysis. We could not assess interscan agreement for FDGMAX and NaFMAX because the 18F-FDG PET/CT and Na18F PET/CT scans were acquired only once.

Statistical analysis

First, FDGMAX and NaFMAX were adjusted for blood activity, injected dose and PET/CT technology by multivariable linear regression, because previous studies had indicated that these parameters significantly affect the quantification of arterial 18F-FDG and Na18F uptake [15, 16]. Second, subject demographics are summarized by descriptive statistics and compared between healthy volunteers and patients using the unpaired Student’s t test, the Mann-Whitney U test, or Fisher’s exact test. Third, the correlations among thoracic aorta FDGMAX, thoracic aorta NaFMAX and thoracic aorta CT calcium burden, were evaluated in terms of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ). Fourth, the associations between cardiovascular risk factors and thoracic aorta FDGMAX, NaFMAX and CT calcium burden were evaluated by univariate regression analysis, and those that were significantly associated were adjusted for age and sex. Linear models were extended by interaction terms to determine if the associations between cardiovascular risk factors and FDGMAX, NaFMAX and CT calcium burden were modified by sex, subject recruitment (i.e. volunteers vs. patients), or prescription medication. Because no significant interactions were observed, results were not separated in relation to sex, volunteers/patients, or prescription medication. To establish independent determinants of thoracic aorta FDGMAX, NaFMAX, and CT calcium burden, variables selected on the basis of the results of the univariate analysis were entered into a multivariable linear regression analysis.

The 10-year risks of CVD based on FRS were then estimated and these risk estimates were compared across quartiles of FDGMAX, NaFMAX and CT calcium burden using factorial analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The relationships between FRS and FDGMAX, NaFMAX and CT calcium burden were also evaluated continuously using Spearman’s ρ and by multivariable linear regression analysis. All statistical analyses were repeated replacing FDGMAX and NaFMAX with the ratios of the maximum tracer activity in the aortic wall to the mean activity in the blood pool (target-to-background ratios, TBR) for 18F-FDG and Na18F (FDG-TBRMAX/MEAN and NaF-TBRMAX/MEAN, respectively). TBR is commonly used to express aortic FDG and NaF uptake, but its use has been criticized [15, 16]. The results of these analyses are reported in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables 5–7). Lastly, we assessed the agreement between the mean CT calcium volumes calculated on CT images from 18F-FDG PET/CT and those calculated on images from Na18F PET/CT in terms of the 95 % limits of agreement according to the method of Bland and Altman [17]. A two-tailed P value below 0.05 was regarded statistically significant. P values and 95 % confidence intervals were determined by a bootstrap of 2,000 samples. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk NY).

Results

Between November 2012 and May 2014 89 healthy volunteers and 50 patients evaluated for chest pain syndromes were prospectively recruited. Several differences in subject demographics were observed between volunteers and patients (Table 1). These differences were mainly related to age, except for smoking habit, family history, HbA1c, FRS, and prescription medication, which remained significantly higher among patients compared with volunteers after adjustment for age. The ages of the study population ranged from 21 – 75 years and FRS ranged from 0.3 – 30.0 %.

Thoracic aorta 18F-FDG uptake was not correlated with either thoracic aorta Na18F uptake or thoracic aorta CT calcium burden, whereas thoracic aorta Na18F uptake was positively correlated with thoracic aorta CT calcium burden (Spearman’s ρ = 0.42, P < 0.001; Fig. 2).

a Thoracic aorta 18F-FDG activity (FDGMAX) versus thoracic aorta Na18F activity (NaFMAX). FDGMAX is not correlated with NaFMAX (Spearman’s ρ = 0.07, P = 0.427). b FDGMAX versus thoracic aorta CT calcium burden. FDGMAX is not correlated with thoracic aorta CT calcium burden (Spearman’s ρ = 0.04, P = 0.654). c NaFMAX versus thoracic aorta CT calcium burden. NaFMAX is positively correlated with thoracic aorta CT calcium burden (Spearman’s ρ = 0.42, P < 0.001). (FDGMAX and NaFMAX are the maximum activity concentrations of 18F-FDG and Na18F, respectively, adjusted for blood activity, injected dose and PET/CT technology)

The results of the univariate analysis are presented in Supplementary Tables 2–4. The multivariable linear regression analysis showed that independent determinants of thoracic aorta 18F-FDG uptake were subject age (0.41 kBq/mL per SD, P = 0.008) and family history (0.66 kBq/mL, P = 0.035), which explained an additional 4 % of the variation in thoracic aorta FDGMAX (adjusted R 2 increased from 0.60 to 0.64, P = 0.001). Blood 18F-FDG activity, injected 18F-FDG dose and PET/CT technology explained the initial 60 % of the variation in the data. The multivariable linear regression analysis showed that independent determinants of thoracic aorta Na18F uptake were subject age (0.25 kBq/mL per SD, P < 0.001), body mass index (0.12 kBq/mL per SD, P = 0.017), renal function (−0.09 kBq/mL per SD, P = 0.022) and thoracic aorta CT calcium burden (0.08 kBq/mL per SD, P = 0.002), which explained an additional 9 % of the variation in thoracic aorta NaFMAX (adjusted R 2 increased from 0.71 to 0.80, P < 0.001). Blood Na18F activity, injected Na18F dose and PET/CT technology explained the initial 71 % of the variation in the data. The multivariable linear regression showed that independent determinants of thoracic aorta CT calcium burden were subject age (1.47 mm3 per SD, P = 0.013) and antihypertensive treatment (10.17 mm3, P = 0.030), which explained 28 % of the variation in thoracic aorta mean CT calcium volume (adjusted R 2 = 0.28, P < 0.001).

FRS was similar in all quartiles of thoracic aorta 18F-FDG uptake (P = 0.492 for a linear trend, Spearman’s ρ = 0.12; P = 0.156). In contrast, FRS increased linearly with each increasing quartile of thoracic aorta Na18F uptake (P < 0.001 for a linear trend, Spearman’s ρ = 0.50; P < 0.001). FRS was on average 3.7 times higher in subjects with thoracic aorta Na18F uptake in the highest quartile compared with those in the lowest quartile of the distribution (15.5 % vs. 4.2 %; P < 0.001). FRS also increased linearly in subjects with increasing quartiles of thoracic aorta CT calcium burden (P < 0.001 for a linear trend, Spearman’s ρ = 0.63; P < 0.001). FRS was on average 3.7 times higher among subjects with thoracic aorta CT calcium burden in the highest quartile compared with those in the lowest two quartiles of the distribution (18.0 % vs. 4.9 %; P < 0.001; Fig. 3). The multivariable linear regression analysis showed that independent determinants of FRS (adjusted R 2 = 0.39, P < 0.001) were thoracic aorta Na18F uptake (β = 0.37, P < 0.001) and thoracic aorta CT calcium burden (β = 0.42, P = 0.002), but not thoracic aorta 18F-FDG uptake (β = 0.10, P = 0.113; Table 2, Fig. 4).

The 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk estimated by the Framingham risk score in relation to quartiles of (a) thoracic aorta 18F-FDG activity (FDGMAX), (b) thoracic aorta Na18F activity (NaFMAX), and (c) thoracic aorta CT calcium burden. CVD risk is similar in all quartiles of thoracic aorta FDGMAX, but increases linearly with each increasing quartile of thoracic aorta NaFMAX (P < 0.001 for a linear trend) and with each increasing quartile of thoracic aorta CT calcium burden (P < 0.001 for a linear trend). s.e. standard error, μ mean

The 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, estimated by the Framingham risk score, in (a) subjects with below or above average thoracic aorta 18F-FDG activity (FDGMAX) and Na18F activity (NaFMAX), (b) subjects with or without thoracic aorta CT calcium burden and below or above average FDGMAX, (c) subjects with or without thoracic aorta CT calcium burden and below or above average NaFMAX. NaFMAX and thoracic aorta CT calcium burden differentiated subjects at high and low CVD risk, whereas FDGMAX did not, μ mean

The agreement between mean calcium burden calculated on CT images from 18F-FDG PET/CT and those calculated from Na18F PET/CT was considered excellent, as indicated by a small interscan difference (Supplementary Figure 1). The results of our study were similar when aortic tracer uptake was expressed as FDG-TBRMAX/MEAN and NaF-TBRMAX/MEAN (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 5–7).

Discussion

In this study, an increased risk of CVD, as estimated by the FRS, was found to be associated with marked increases in vascular calcification metabolism, as assessed by Na18F PET/CT imaging, and vascular calcium burden, as assessed by CT imaging, but was not associated with arterial inflammation, as assessed by 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. These findings support the use of arterial Na18F PET/CT imaging for identifying the vulnerable patient, but the value of arterial 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging is less clear.

Arterial inflammation and vascular calcification are regarded as key processes in the pathogenesis of various CVDs, in particular atherosclerosis [4, 5]. Atherosclerotic plaque inflammation is characterized by accumulation of macrophages, which are attracted to plaques in response to the retention of lipids in the arterial intima [18]. Plaque macrophages secrete chemokines, proinflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases, which contribute to a nonresolving inflammatory response that leads to plaque hypoxia, plaque necrosis, weakening of the protective fibrous cap and, ultimately, plaque rupture [18, 19]. Plaque rupture is considered the most frequent cause of adverse cardiovascular events, such as acute coronary syndromes and stroke [19, 20]. In response to chronic inflammation and necrosis, atherosclerotic plaques calcify [21]. It is believed that atherosclerotic plaque calcification retards the inflammatory response, stabilizes the atherosclerotic plaque, and reduces the risk of plaque rupture. Nonetheless, the earliest stages of plaque calcification are associated with increased plaque instability and an elevated risk of rupture [22], whereas only advanced stages of plaque calcification are associated with plaque stabilization [23]. A possible explanation for the increased risk of plaque rupture during early stages of plaque calcification is that plaque microcalcifications increase local tissue stress, which facilitate plaque vulnerability [24]. Although plaque calcification is associated with plaque stabilization, the presence and degree of vascular macrocalcifications is strongly predictive of adverse cardiovascular events [7]. It appears that vascular calcification, independent of its association with plaque stability, is a marker of overall atherosclerotic disease burden, and thus, the vulnerable patient [3, 25].

By inference, imaging techniques aimed at visualizing arterial inflammation and vascular calcification are potent markers of CVD risk. 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging can noninvasively assess arterial inflammation, whereas Na18F PET/CT and CT imaging can noninvasively assess vascular calcification. 18F-FDG uptake reflects the rate of glycolysis, which is particularly increased in atherosclerotic plaques that retain macrophages [26] and plaques that undergo hypoxic stress [27]. In addition to atherosclerotic plaque, aortic 18F-FDG retention has been linked to formation of aneurysms and dissection of the aorta, which are diseases associated with inflammation of the arterial media and arterial adventitia [28]. It has been reported that arterial 18F-FDG uptake increases in proportion to CVD risk factors [29] and that aortic 18F-FDG retention predicts adverse cardiovascular events beyond traditional CVD risk factors [6]. Na18F uptake reflects the active exchange of hydroxyl groups of hydroxyapatite crystals for fluoride producing fluorapatite [30]. This process is believed to reflect calcification metabolism of osseous tissue, including calcification of atherosclerotic plaque [31–33]. While calcification of atherosclerotic plaque, which is regarded as a disease of the arterial intima, arterial Na18F retention is believed to also reflect calcification of the arterial media, a condition associated with arterial stiffening, increased pulse pressure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and reduced myocardial perfusion [34, 35]. Similar to arterial 18F-FDG retention, arterial Na18F retention has also been reported to increase in proportion to CVD risk factors [31, 32]. CT imaging targets structural vascular calcifications. Numerous follow-up studies have shown that the vascular calcium burden, as detected by CT imaging, is a strong independent marker of CVD risk [7, 8].

This study confirmed the findings from previous investigations. First, this study confirmed that arterial 18F-FDG retention is not correlated with either arterial Na18F retention [10] or CT calcium burden [9]. A previous study has shown that 18F-FDG-avid plaques rarely (∼7 %) accumulate Na18F and only occasionally (∼15 %) colocate with structural calcium deposits [9]. These findings suggest that arterial retention of 18F-FDG and Na18F represent different stages of the cardiovascular atherosclerotic disease process and their imaging may help differentiate early from advanced stages of the disease [9] or may carry independent prognostic value. Second, this study confirmed that arterial Na18F retention is positively correlated with CT calcium burden [9]. A previous study has shown that structural calcium deposits are present in approximately 77 % of Na18F-avid plaques, whereas only 21 % of vascular macrocalcifications retain Na18F [9]. These findings suggest that arterial Na18F retention may discriminate active from indolent vascular calcifications, associated with vulnerable and stabilized plaques, respectively [10]. Our data seem to confirm this suggestion. In those with CT calcium burden, but below average aortic Na18F uptake, CVD risk was substantially lower compared to those with CT calcium burden and above average aortic Na18F uptake (10.5 % vs. 17.5 %). Lastly, this study confirmed that CVD risk, as estimated by the FRS, increases linearly with increasing arterial Na18F uptake and CT calcium burden [10, 36].

Despite confirming several findings from previous investigations, our observations challenge the notion that arterial inflammation, as assessed by 18F-FDG PET/CT, is associated with an elevated risk of CVD [6]. There may be several explanations for this discrepant finding. First, this study evaluated subjects at low CVD risk (i.e. median FRS of 6 %), whereas the majority of studies investigating arterial 18F-FDG retention in relation to CVD risk evaluated subjects at high CVD risk [6]. Therefore, our study might have detected early stages of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation, but not later stages of inflammation that are associated with plaque and patient vulnerability. Second, this study included subjects with a broad age range, that is between 21 and 75 years. Therefore, it can be assumed that subjects with a spectrum of atherosclerosis severity, ranging from mild to severe disease were included. Both fatty streaks (the hallmark of mild atherosclerosis) and high-risk vulnerable plaques (the hallmark of severe atherosclerosis) are densely populated by macrophages [18]. Because 18F-FDG is primarily retained in plaque macrophages [37–39], differentiation of fatty streaks from high-risk vulnerable plaques, and thus differentiation of mild from severe atherosclerosis, may be difficult by 18F-FDG PET/CT. Third, this study estimated CVD risk solely based on FRS. A previous study has shown that aortic 18F-FDG retention predicts CVD risk beyond FRS [6], and also demonstrated that adding the aortic 18F-FDG retention index to FRS results in a net reclassification improvement of approximately 25 % compared with FRS alone [6]. Because this study estimated CVD risk solely via FRS, the incremental value of arterial 18F-FDG retention over FRS in predicting CVD risk could not be assessed. The three considerations mentioned above may explain the lack of association between arterial 18F-FDG retention and CVD risk found in this study.

Strengths and limitations

An important strength of the present study is that we prospectively investigated the relationship between CVD risk and arterial inflammation, vascular calcification metabolism, and vascular calcium burden in a heterogeneous group of subjects at low CVD risk. Previous studies that have investigated similar relationships either were performed retrospectively in oncology patients [9] or involved exclusively elderly patients with advanced CVD [10]. Such studies may be limited by imaging protocols not necessarily optimized for imaging arteries, by selection bias, or by both. In contrast, this study was performed prospectively, included a heterogeneous group of subjects at low CVD risk, and utilized imaging protocols optimized for artery imaging [13–15]. Thus we were able to demonstrate that CVD risk is positively associated with increases in thoracic aorta Na18F uptake and thoracic aortic CT calcium burden, but is not associated with thoracic aorta 18F-FDG uptake.

The findings of this study, however, should be interpreted in light of three limitations. First, CVD risk was estimated in terms of the FRS. Although the revised FRS performs well in terms of discrimination and calibration [12], it still tends to overestimate risk in those at low CVD risk and underestimates risk in those at high CVD risk. Our estimates of CVD risk may therefore be inaccurate and there may be bias in the associations between CVD risk and our imaging findings. However, because of the cross-sectional nature of our study, we relied on an estimated CVD risk. Second, the relationships between CVD risk and arterial inflammation, vascular calcification metabolism, and vascular calcium burden were evaluated in a cross-sectional study. A previous study involving serial 18F-FDG PET/CT examinations demonstrated that baseline arterial 18F-FDG uptake predicts the finding of vascular calcium deposits on the follow-up examination, suggesting a temporal relationship between arterial inflammation and vascular calcification [40]. Temporal relationships are difficult to assess in cross-sectional studies and a longitudinal approach is preferred for such an evaluation. Therefore, our finding that arterial inflammation is not related either to vascular calcification metabolism or to vascular calcium burden could be attributed to our cross-sectional design. Third, ethical considerations prevented collection of arterial specimens for histological examination. Therefore, we could not relate our imaging findings to the exact structure, biological composition and inflammatory state of the detected atherosclerotic plaques [9]. Substantiating arterial 18F-FDG and Na18F uptake by histopathology, preferably in the early stages of the disease, might have contributed to a better understanding of the metabolic pathways that govern CVD risk.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that an unfavourable cardiovascular risk profile is associated with marked increases in thoracic aorta vascular calcification metabolism and calcium burden, but not arterial inflammation. Our findings support the use of arterial Na18F PET/CT imaging for identifying the vulnerable patient, but the value of arterial 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging is less clear. Nonetheless, prospective long-term follow-up studies are required to assess the risk stratification abilities of arterial 18F-FDG and Na18F PET/CT imaging beyond standard approaches, such as the FRS and CT calcium score.

References

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–e322.

Franco M, Cooper RS, Bilal U, Fuster V. Challenges and opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention. Am J Med. 2011;124:95–102.

Arbab-Zadeh A, Fuster V. The myth of the "vulnerable plaque": transitioning from a focus on individual lesions to atherosclerotic disease burden for coronary artery disease risk assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:846–855.

Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695.

Demer LL, Tintut Y. Vascular calcification: pathobiology of a multifaceted disease. Circulation. 2008;117:2938–2948.

Figueroa AL, Abdelbaky A, Truong QA, et al. Measurement of arterial activity on routine FDG PET/CT images improves prediction of risk of future CV events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:1250–1259.

Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, et al. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification: observations from a registry of 25,253 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1860–1870.

Hou ZH, Lu B, Gao Y, et al. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography and calcium score for major adverse cardiac events in outpatients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:990–999.

Derlin T, Toth Z, Papp L, et al. Correlation of inflammation assessed by 18F-FDG PET, active mineral deposition assessed by 18F-fluoride PET, and vascular calcification in atherosclerotic plaque: a dual-tracer PET/CT study. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1020–1027.

Dweck MR, Chow MW, Joshi NV, et al. Coronary arterial 18F-sodium fluoride uptake: a novel marker of plaque biology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1539–1548.

Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987–1003.

D’Agostino Sr RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753.

Blomberg BA, Thomassen A, Takx RA, et al. Delayed 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT imaging improves quantitation of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation: results from the CAMONA study. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21:588–597.

Blomberg BA, Thomassen A, Takx RA, et al. Delayed sodium 18F-fluoride PET/CT imaging does not improve quantification of vascular calcification metabolism: results from the CAMONA study. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21:293–304.

Blomberg BA, Thomassen A, de Jong PA, et al. Impact of personal characteristics and technical factors on quantification of sodium 18F-fluoride uptake in human arteries: prospective evaluation of healthy subjects. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1534–1540.

Huet P, Burg S, Le Guludec D, Hyafil F, Buvat I. Variability and uncertainty of FDG PET imaging protocols for assessing inflammation in atherosclerosis: suggestions for improvement. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:552–559.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310.

Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145:341–355.

Libby P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2004–2013.

Weber C, Noels H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med. 2011;17:1410–1422.

Demer LL, Tintut Y. Inflammatory, metabolic, and genetic mechanisms of vascular calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:715–723.

Ehara S, Kobayashi Y, Yoshiyama M, et al. Spotty calcification typifies the culprit plaque in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2004;110:3424–3429.

Otsuka F, Finn AV, Virmani R. Do vulnerable and ruptured plaques hide in heavily calcified arteries? Atherosclerosis. 2013;229:34–37.

Kelly-Arnold A, Maldonado N, Laudier D, Aikawa E, Cardoso L, Weinbaum S. Revised microcalcification hypothesis for fibrous cap rupture in human coronary arteries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10741–10746.

Mauriello A, Servadei F, Zoccai GB, et al. Coronary calcification identifies the vulnerable patient rather than the vulnerable plaque. Atherosclerosis. 2013;229:124–129.

Tarkin JM, Joshi FR, Rudd JH. PET imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:443–457.

Folco EJ, Sheikine Y, Rocha VZ, et al. Hypoxia but not inflammation augments glucose uptake in human macrophages: implications for imaging atherosclerosis with 18fluorine-labeled 2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:603–614.

Golestani R, Sadeghi MM. Emergence of molecular imaging of aortic aneurysm: implications for risk stratification and management. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21:251–267.

Blomberg BA, Hoilund-Carlsen PF. [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose PET imaging of atherosclerosis. PET Clin. 2015;10:1–7.

Czernin J, Satyamurthy N, Schiepers C. Molecular mechanisms of bone 18F-NaF deposition. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1826–1829.

Derlin T, Richter U, Bannas P, et al. Feasibility of 18F-sodium fluoride PET/CT for imaging of atherosclerotic plaque. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:862–865.

Derlin T, Wisotzki C, Richter U, et al. In vivo imaging of mineral deposition in carotid plaque using 18F-sodium fluoride PET/CT: correlation with atherogenic risk factors. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:362–368.

Joshi NV, Vesey AT, Williams MC, et al. 18F-fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet. 2014;383:705–713.

Johnson LL. Novel application of 18F-sodium fluoride an old tracer to a clinically neglected condition. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20:506–509.

Janssen T, Bannas P, Herrmann J, et al. Association of linear 18F-sodium fluoride accumulation in femoral arteries as a measure of diffuse calcification with cardiovascular risk factors: a PET/CT study. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20:569–577.

Morbelli S, Fiz F, Piccardo A, et al. Divergent determinants of 18F-NaF uptake and visible calcium deposition in large arteries: relationship with Framingham risk score. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30:439–447.

Rudd JH, Warburton EA, Fryer TD, et al. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2002;105:2708–2711.

Tawakol A, Migrino RQ, Bashian GG, et al. In vivo 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging provides a noninvasive measure of carotid plaque inflammation in patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1818–1824.

Figueroa AL, Subramanian SS, Cury RC, et al. Distribution of inflammation within carotid atherosclerotic plaques with high-risk morphological features: a comparison between positron emission tomography activity, plaque morphology, and histopathology. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:69–77.

Abdelbaky A, Corsini E, Figueroa AL, et al. Focal arterial inflammation precedes subsequent calcification in the same location: a longitudinal FDG-PET/CT study. Circulation Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:747–754.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the CAMONA study and the study participants for their valuable contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the MD/PhD ‘Alexandre Suerman’ programme, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands, the Anna Marie and Christian Rasmussen’s Memorial Foundation, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark, and the Jørgen and Gisela Thrane’s Philanthropic Research Foundation, Broager, Denmark.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 247 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Blomberg, B.A., de Jong, P.A., Thomassen, A. et al. Thoracic aorta calcification but not inflammation is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk: results of the CAMONA study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 44, 249–258 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-016-3552-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-016-3552-9