Abstract

Background

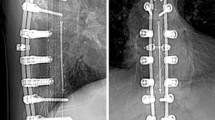

Evaluation of the child with spinal fusion hardware and concern for infection is challenging because of hardware artifact with standard imaging (CT and MRI) and difficult physical examination. Studies using 18F-FDG PET/CT combine the benefit of functional imaging with anatomical localization.

Objective

To discuss a case series of children and young adults with spinal fusion hardware and clinical concern for hardware infection. These people underwent FDG PET/CT imaging to determine the site of infection.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective review of whole-body FDG PET/CT scans at a tertiary children’s hospital from December 2009 to January 2012 in children and young adults with spinal hardware and suspected hardware infection. The PET/CT scan findings were correlated with pertinent clinical information including laboratory values of inflammatory markers, postoperative notes and pathology results to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of FDG PET/CT. An exempt status for this retrospective review was approved by the Institution Review Board.

Results

Twenty-five FDG PET/CT scans were performed in 20 patients. Spinal fusion hardware infection was confirmed surgically and pathologically in six patients. The most common FDG PET/CT finding in patients with hardware infection was increased FDG uptake in the soft tissue and bone immediately adjacent to the posterior spinal fusion rods at multiple contiguous vertebral levels. Noninfectious hardware complications were diagnosed in ten patients and proved surgically in four. Alternative sources of infection were diagnosed by FDG PET/CT in seven patients (five with pneumonia, one with pyonephrosis and one with superficial wound infections).

Conclusion

FDG PET/CT is helpful in evaluation of children and young adults with concern for spinal hardware infection. Noninfectious hardware complications and alternative sources of infection, including pneumonia and pyonephrosis, can be diagnosed. FDG PET/CT should be the first-line cross-sectional imaging study in patients with suspected spinal hardware infection. Because pneumonia was diagnosed as often as spinal hardware infection, initial chest radiography should also be performed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Slone RM, MacMillan M, Montgomery WJ et al (1993) Spinal fixation. Part 2. Fixation techniques and hardware for the thoracic and lumbosacral spine. Radiographics 13:521–543

Sharif HS (1991) Role of MR imaging in the management of spinal infections. AJR Am J Roentgenol 158:1333–1345

Heller RM, Szalay EA, Green NE et al (1988) Disc space infection in children: magnetic resonance imaging. Radiol Clin North Am 26:207–209

Parisi MT (2011) Functional imaging of infection: convention nuclear medicine agents and the expanding role of 18F-FDG PET. Pediatr Radiol 41:803–810

Gemmel F, Fijk PC, Collins JM et al (2010) Expanding the role of 18 F-fluoro-D-deoxyglucose PET and PET/CT in spinal infections. Eur Spine J 19:540–551

Mochizuki T, Tsukamoto E, Kuge Y et al (2001) FDG uptake and glucose transporter subtype expressions in experimental tumor and inflammation models. J Nucl Med 42:1551–1555

Paik JY, Lee KH, Choe YS et al (2004) Augmented 18F-FDG uptake in activated monocytes occurs during the priming process and involves tyrosine kinases and protein kinase C. J Nucl Med 45:124–128

Zhuang H, Alavi A (2002) 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomographic imaging in the detection and monitoring of infection and inflammation. Semin Nucl Med 32:47–59

De Winter F, Gemmel F, Van de Wiele C et al (2003) 18-fluorine fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for the diagnosis of infection in the post-operative spine. Spine 28:1314–1319

Chacko TK, Zhuang H, Stevenson K et al (2002) The importance of the location of fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in periprosthetic infection in painful hip prostheses. Nucl Med Commun 23:851–855

Van der Bruggen W, Bleeker-Rovers CP, Boerman OC et al (2010) PET and SPECT in osteomyelitis and prosthetic bone and joint infections: a systematic review. Semin Nucl Med 40:3–15

Stumpe KD, Dazzi H, Schaffner A et al (2000) Infection imaging using whole-body FDG-PET. Eur J Nucl Med 27:822–832

Bockisch A, Beyer T, Antoch G et al (2004) Positron emission tomography/computed tomography – imaging protocols, artifacts, and pitfalls. Mol Imaging Biol 6:188–199

Kamel EM, Burger C, Buck A et al (2002) Impact of metallic dental implants on CT-based attenuation correction on a combined PET/CT scanner. Eur Radiol 13:724–728

Acknowledgement

This work was presented at the 2012 Society for Pediatric Radiology national meeting April 2012, San Francisco, CA (abstract PA-001).

Conflicts of interest

None to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bagrosky, B.M., Hayes, K.L., Koo, P.J. et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT evaluation of children and young adults with suspected spinal fusion hardware infection. Pediatr Radiol 43, 991–1000 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-013-2654-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-013-2654-9