Abstract

Background

Intraspinal rib head dislocation is an important but under-recognized consequence of dystrophic scoliosis in patients with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1).

Objective

To present clinical and imaging findings of intraspinal rib head dislocation in NF1.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed clinical presentation, imaging, operative reports and post-operative courses in four NF1 patients with intraspinal rib head dislocation and dystrophic scoliosis. We also reviewed 17 cases from the English literature.

Results

In each of our four cases of intraspinal rib head dislocation, a single rib head was dislocated on the convex apex of the curve, most often in the mid- to lower thoracic region. Cord compression occurred in half of these patients. Analysis of the literature yielded similar findings. Only three cases in the literature demonstrates the MRI appearance of this entity; most employ CT. All of our cases include both MRI and CT; we review the subtle findings on MRI.

Conclusion

Although intraspinal rib head dislocation is readily apparent on CT, sometimes MRI is the only cross-sectional imaging performed. It is essential that radiologists become familiar with this entity, as subtle findings have significant implications for surgical management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), also known as von Recklinghausen disease, involves the spine in 10% to 69% of patients [1, 2]. Kyphoscoliosis is the most common spinal deformity and presents in dystrophic and nondystrophic forms [2, 3]. Nondystrophic scoliosis resembles idiopathic scoliosis and is usually a long-segment biconvex curve secondary to leg length discrepancy [2]. Dystrophic scoliosis, on the other hand, is characterized by progressive, sharply angulated short-segment curvature with severe wedging, rotation and scalloping of the apical vertebral bodies [3]. Foraminal enlargement, spindling of the transverse processes and penciling of the apical ribs can also be seen with dystrophic scoliosis [2]. A few case reports have described spinal canal penetration by dislocated ribs in patients with NF1 and dystrophic scoliosis. Although most are asymptomatic, spinal cord compression with resultant paraparesis and paraplegia have been documented both before and after spinal instrumentation [1, 4–15].

We report the clinical and radiographic findings of four cases of rib head dislocation into the spinal canal in patients with dystrophic scoliosis secondary to NF1, including radiographs, CTs and MRIs, as well as clinical manifestations and management strategies in this uncommon but important entity.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted with IRB review and approval. We conducted a retrospective review of imaging studies performed on four children with NF1 referred for surgery at our institutions with rib head protrusion into the spinal canal identified on preoperative imaging and confirmed at surgery. Clinical history, imaging studies, reports and operative reports, and post-operative courses were reviewed. We also present an analysis of children with this entity in the English literature from 1986 to 2009.

Results

Between 2003 and 2009, rib head dislocation into the spinal canal was found at our institutions in four children, ranging in age from 9 to 14 years old. Radiographs, CTs, MRIs, and operative reports were available in all four, along with clinical follow-up from several months to 6 years. Table 1 summarizes clinical and imaging findings. Table 2 summarizes the 17 cases that have been reported in the English literature.

Case 1 is a 14-year-old boy with severe progressive scoliosis who complained of neck and upper back pain. He was mildly tender to palpation at the apex of his curve. He had slight hyperreflexia of the left lower extremity (3+) and a few beats of ankle clonus bilaterally. The preoperative spine radiograph (Fig. 1) demonstrates penciling and displacement of the fourth and fifth ribs at the apex of the curve, although only the fourth was in an abnormal position on CT and MRI. Rib head resection can be seen on the postoperative spine radiograph.

Case 1. a Radiograph shows levoscoliosis of the upper cervical spine with penciling deformity and medial positioning of the left fourth rib head (arrow) relative to the pedicle. Note that the fifth rib is also malpositioned, although it was not intraspinal on cross-sectional imaging. b, c Axial CT and T2-W MR images demonstrate intraspinal displacement of the left fourth rib head (arrow) with narrowing of the spinal canal but without cord impingement. d Post-operative spine radiograph shows interval spinal rod and pedicular screw placement with improved levoscoliosis. The displaced left fourth rib head has been resected (arrow)

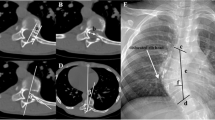

Case 2 is an 11-year-old asymptomatic girl with severe kyphoscoliosis. The preoperative spine CT and MRI demonstrate rib head displacement into the spinal canal at the apex of the curve, with cord impingement on MRI (Fig. 2).

Case 3 is an 11-year-old boy with progressive but asymptomatic scoliosis and kyphosis. Spine CT and MRI demonstrate no evidence of enlarged neural foramina or vertebral scalloping, but displacement of the right ninth rib with spinal canal narrowing (Fig. 3).

Case 3. a Axial CT demonstrates displacement of the right ninth rib head intraspinally. b, c Contiguous post-contrast axial T1-W MR images show the dislocated rib head (white arrow) with narrowing of the spinal canal but no cord compromise. The cord (black arrow) is located at the concave side of the curvature

Case 4 is a 9-year-old girl with progressive scoliosis who developed back pain and right foot weakness as well as hyperreflexia of both lower extremities and sustained ankle clonus. CT and MRI reveal a neurofibroma destroying portions of the T4 to T6 vertebral bodies and filling adjacent neural foramina, with intraspinal displacement of the right sixth rib (Fig. 4). MRI also shows cord compression by the displaced rib head.

Case 4. a Axial CT shows widening of the neural foramina with intraspinal displacement of the right sixth rib head (black arrow). Linear ossific density to the right of the displaced rib head represents the superior articulating facet of the lower vertebrae. b Coronal T1-W post-contrast MRI reveals an enhancing right paraspinous neurofibroma (arrows) extending into the spinal canal at the apex of the curve. There is displacement of the cord to the left by the dislocated right sixth rib head (arrowhead)

Discussion

Dystrophic scoliosis in children with NF is typically characterized by a short-segment, sharply angulated curve with associated wedging and scalloping of the vertebral bodies. It can be accompanied by vertebral body rotation, widening of the intervertebral foramina and penciling of rib heads. These abnormalities predispose children with dystrophic scoliosis to intraspinal rib head dislocation [1]. To our knowledge, a total of 21 (including our four) cases of intraspinal rib head dislocation in NF1 patients have been reported in the English literature. The majority of documented cases of intraspinal rib head dislocation in NF1 occur during the teenage years (ages range from 5 to 16 years) [1, 4–15], with no gender predisposition. Although generally asymptomatic, the clinical presentation of intraspinal rib displacement varies. Two of our patients had moderate symptoms; the other two were essentially asymptomatic. This parallels the cases we found in the literature, with nine of the 15 for whom this information was available being essentially asymptomatic. The other six had neurological symptoms ranging from mild sensory and motor deficits to paraplegia and paraparesis.

Both Khoshhal and Ellis [10] and Cappella et al. [15] describe the postoperative complication of rib head dislocation in NF patients who developed paraparesis several weeks after posterior spinal fusion without recognition of or attempt at correcting rib head protrusion. In retrospect, rib head protrusion had been present on a preoperative MRI in Cappella’s patient but had not been recognized. Both cases illustrate the importance of delineating the presence of intraspinal rib head dislocation preoperatively since surgical correction of the scoliosis can bring the displaced spinal cord to its more anatomical location and result in higher risk of cord impingement by the unrecognized dislocated rib head.

Although paraparesis caused by intraspinal rib head dislocation is rare, it remains a diagnostic consideration in NF1 patients who develop acute or progressive neurological symptoms. Of the 17 cases presented in the literature for which clinical information is available, six had evidence of cord compromise or impingement by the displaced rib head. Our case series reveals a similar incidence, with two of our four patients demonstrating such findings.

In our cases, as in the literature, rib head dislocation occurred at the convex side of the apex of the scoliosis, most often involving the mid- to lower ribs. Furthermore, a single rib was involved in the majority of cases (10 out of 17) [5, 8–15], and in all of our patients.

There is no clear consensus regarding the treatment of intraspinal rib head dislocation in dystrophic scoliosis, with most favoring excision of the rib head (under unusual circumstances, the rib head may be left in place) [14]. However, preoperative recognition is essential for surgical planning so that the relationship of rib to cord can be assessed intra-operatively and manipulation performed with appropriate caution.

Spine radiography is usually the initial imaging for scoliosis, but radiographic diagnosis of intraspinal rib head dislocation is extremely difficult. All reported intraspinal rib head dislocations have been reliably demonstrated by CT, and our cases are no exception. CT myelography accurately depicts the relationship between the spinal cord and the dislocated rib, but MRI demonstrates this noninvasively.

However, MRI – excellent for delineating cord and paraspinous soft-tissue pathology – is sometimes the only cross-sectional preoperative imaging performed. Concern over radiation exposure might limit preoperative CT further in the future, especially if critical findings like rib head dislocation can be diagnosed accurately with MRI. Delineation of bony anatomy is certainly more difficult with MRI than with CT, but MRI can demonstrate intraspinal rib head dislocation, as in our four patients. In our experience, intraspinal displacement of rib heads is best shown on T2-weighted images in the axial and coronal planes.

Conclusion

Intraspinal rib head dislocation in NF1 is an uncommon entity with significant clinical and surgical implications. Although affected patients are generally asymptomatic, presentation ranges from mild back pain to weakness and other myelopathic symptoms. Clinical diagnosis is difficult, and radiological diagnosis requires close scrutiny for subtle findings, such as medial and superior positioning of a penciled rib head – and even then it is extremely challenging. Intraspinal rib head dislocation is reliably diagnosed with CT in all reported cases in the literature and in the cases we present. However, MRI – with its excellent delineation of soft tissues and cord, as well as its lack of radiation – is often performed without CT in the work-up of children with scoliosis, and coronal and axial T2-W sequences can demonstrate intraspinal rib head dislocation. Evaluation of osseous structures with MRI is certainly more difficult than with CT, and it is essential that radiologists become familiar with rib head displacement, as subtle findings have significant implications for surgical management.

References

Akbarnia BA, Gabriel KR, Beckman E et al (1992) Prevalence of scoliosis in neurofibromatosis. Spine 17(suppl 8):244–248

Crawford AH, Bagamery N (1986) Osseous manifestations of neurofibromatosis in childhood. J Pediatr Orthop 6:72–88

Winter RB, Moe JH, Bradford DS et al (1979) Spine deformity in neurofibromatosis. A review of one hundred and two patients. J Bone Jt Surg Am 61:677–694

Barker D, Wright E, Nguyen K et al (1987) Gene for Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis is in the pericentromeric region of chromosome 17. Science 236:1098–1102

Dacher JN, Zakine S, Monroc M et al (1995) Rib displacement threatening the spinal cord in a scoliotic child with neurofibromatosis. Pediatr Radiol 25:58–59

Deguchi M, Kawakami N, Saito H et al (1995) Paraparesis after rib penetration of the spinal canal in neurofibromatosis scoliosis. J Spinal Disord 8:363–367

Flood BM, Butt WP, Dickson RA (1986) Rib penetration of the intervertebral foramina in neurofibromatosis. Spine 11:172–174

Gkiokas A, Hadzimichalis S, Vasiliadis E et al (2006) Painful rib hump: a new clinical sign for detecting intraspinal rib displacement in scoliosis due to neurofibromatosis. Scoliosis 1:10

Kamath SV, Kleinman PK, Ragland RL et al (1995) Intraspinal dislocation of the rib in neurofibromatosis: a case report. Pediatr Radiol 25:538–539

Khoshhal KI, Ellis RD (2000) Paraparesis after posterior spinal fusion in neurofibromatosis secondary to rib displacement: case report and literature review. J Pediatr Orthop 20:799–801

Major MR, Huizenga BA (1988) Spinal cord compression by displaced ribs in neurofibromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 70:1100–1102

Mukhtar IA, Letts M, Kontio K (2005) Spinal cord impingement by a displaced rib in scoliosis due to neurofibromatosis. Can J Surg 48:414–415

Crawford AH, Parikh S, Schorry EK et al (2007) The immature spine in type-1 neurofibromatosis. J Bone Jt Surg Am 1(89 Suppl):123–142

Yalcin N, Bar-on E, Yazici M (2008) Impingement of spinal cord by dislocated rib in dystrophic scoliosis secondary to neurofibromatosis type 1. Spine 33:E881–E886

Cappella M, Bettini N, Dema E et al (2008) Late post-operative paraparesis after rib penetration of the spinal canal in a patient with neurofibromatosis scoliosis. J Orthop Traumatol 9:163–166

Acknowledgement

We thank Mrs. Julie A. Ostoich-Prather for her assistance with the preparation of the images.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ton, J., Stein-Wexler, R., Yen, P. et al. Rib head protrusion into the central canal in type 1 neurofibromatosis. Pediatr Radiol 40, 1902–1909 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-010-1789-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-010-1789-1