Abstract

Background

Posterior rib fractures in young children have a high positive predictive value for non-accidental injury (NAI). Combined data of five studies on birth trauma (115,756 live births) showed no cases of rib fractures resulting from birth trauma. There have, however, been sporadic cases reported in the literature.

Objective

We present three neonates with both posterior rib fractures and ipsilateral clavicular fractures resulting from birth trauma. A review of the literature is also presented. The common denominator and a possible mechanical aetiology are discussed.

Materials and methods

In total, 13 cases of definitive birth-related posterior rib fractures were identified.

Results

Nearly all (9/10) posterior rib fractures were (as far as reported in the original publications) in the midline. In 12 of the 13 children, birth weight was high and in 7 children birth was complicated by shoulder dystocia. An interesting finding was that in cases where a clavicular fracture was present, this was on the ipsilateral side.

Conclusion

Radiologists, when presented with a neonate with posterior rib fractures, should be aware of this rare differential diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rib fractures in young children, especially posterior rib fractures, are deemed to be highly specific for non-accidental injury (NAI) [1, 2]. Barsness et al. [3] reported a positive predictive value (PPV) of a rib fracture as an indicator of NAI to be 95%. However, other causes for the occurrence of rib fractures in the young child have been reported, and these should be considered when rib fractures are found. One of the rarer causes that has been reported in the literature is rib fractures resulting from delivery [4–12]. We report here three neonates with rib fractures resulting from delivery and one other case that most likely resulted from delivery. A discussion of the relevant literature is presented.

Based on our three patients and a review of the literature totalling 13 cases we present some features encountered in neonates with possible delivery-related rib fractures. This may be of help to both paediatricians and paediatric radiologists in differentiating between delivery-related and NAI when confronted with a neonate with rib fractures.

Case reports

Case 1

After an uncomplicated pregnancy, a girl (birth weight 5,656 g) was born at a gestational age of 41 weeks to a G5P4 mother. Vaginal delivery was complicated by shoulder dystocia, and directly after birth a clavicular fracture was noted by the attending physician. The Apgar scores were 8/10. Because of developing respiratory distress, she was transferred to the NICU of a tertiary referral centre where she was placed on ventilation support for 3 days. On the routine radiograph, mid-posterior rib fractures (4th to 9th) and an ipsilateral clavicular fracture were seen (Fig. 1). A skeletal survey was not performed. Laboratory examinations, according to the local NAI protocol, were performed and showed no abnormalities. Based on clinical evaluation the constellation of rib and the clavicular fractures were deemed to be caused by traumatic compression during birth.

Case 2

After an uncomplicated pregnancy a boy was born at a gestational age of 42 weeks to a G2P0 mother. The first pregnancy had ended with a spontaneous abortion. Delivery was complicated by a vertex cephalic presentation of the fetus. In light of this presentation a decision was made to use forceps, which was complicated by shoulder dystocia. Birth weight was 5,020 g (>97th centile) and Apgar scores were 2/8/9. On physical examination the newborn was seen to be macrosomic with caput succedaneum and Erb’s paresis of the right arm. The newborn seemed to be in pain. The morning after birth a chest radiograph showed a left clavicular fracture and three mid-posterior rib fractures (4th and 5th) on the left side (Fig. 2). A skeletal survey was not performed. Laboratory examinations, according to the local NAI protocol, were performed and showed no abnormalities. As the newborn had not left the hospital between birth and the radiography, the fractures were presumed to result from birth trauma.

Case 3

After an uncomplicated pregnancy a boy was born at a gestational age of 41+1 weeks (birth weight 4,300 g) to a G4P3 mother. He was born at home, a practice that is still common in the Netherlands. According to the midwife, birth was difficult and complicated by shoulder dystocia. However, the Apgar scores were 8/9/10. The maternity home-care assistant noted a click in the left clavicle during bathing. Under the suspicion of a clavicular fracture he was transferred to the hospital on the day after birth. Clinical examination showed an asymmetrical Moro reflex and a haematoma over the left clavicle. A chest radiograph showed a left clavicular fracture and, additionally, left-sided mid-posterior rib fractures (5th to 8th) (Fig. 3). Clinical history and a thorough work-up (a skeletal survey was not performed; laboratory examinations according to the local NAI protocol were performed and showed no abnormalities) showed no signs of bone disorders or indications of child abuse.

Case 4

A 7-week-old girl was admitted to a community hospital because of respiratory distress caused by respiratory syncytial virus. The clinical history revealed a relatively uncomplicated pregnancy, although there was maternal diabetes, with delivery at a gestational age of 38 weeks. The mother was G3P2. Delivery, although rapid, was complicated with shoulder dystocia for which a McRoberts manoeuvre was performed. Birth weight was 5,070 g (>97th centile); Apgar scores were 6, 8 and 9 after 1, 5 and 10 min, respectively. Physical examination showed no abnormalities. Two days after birth it was noted that the right shoulder did not move properly and the Moro reflex was asymmetrical. On physical examination a fracture of the right clavicle was found for which the arm was immobilized.

A chest radiograph on admission showed the clinically known clavicle fracture and additional mid-posterior rib fractures with mature callus formation (Fig. 4). Clinical history and a thorough work-up showed no signs of bone disorders or signs of child abuse. It was decided that these fractures, given the difficult delivery, the size of the baby and the discovery of the clavicular fracture on the second day of life, were due to trauma during delivery. We could not be certain that between birth and day 2 of life a non-accidental incident had not taken place; therefore we did not include this patient in Table 1 and the discussion of our other three patients. As this case is clearly an example of the difficulties faced by clinicians and radiologists, we thought it worthwhile to present it as an additional case.

Discussion

Fractures in full-term neonates, even after an uneventful delivery, are a well-known finding; fractures of the clavicle, long bones, spine and skull have been described [13–19]. Fractures of the mandible, epiphyseal fractures and classic metaphyseal corner fractures have also been reported, but are less common [20–22].

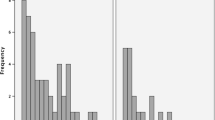

In the Dutch perinatal registry, 1,174 (0.74%) fractures were reported in 158,035 hospitalized full-term neonates between 1997 and 2004 [23]. None of these children had reported rib fractures. As not all neonates with fractures, such as a fracture of the clavicle, will be admitted to a hospital, this is an underestimation of the true incidence of neonatal fractures. Data from five studies on birth trauma, yielding data on a total of 115,756 live births, showed no cases of rib fractures [24–28]. There have, however, been sporadic reports on rib fractures in neonates after birth in the medical literature (Table 1) [4–7, 9–12]. We found a total of ten reports of neonates with birth trauma-related rib fractures; adding our own cases to these yielded a total of 13 cases. The common denominator in nearly all cases was that the neonates were large with a difficult delivery; a significant proportion (7/13) presented with shoulder dystocia. This is in keeping with previous reports on obstetric trauma [27, 29]. In neonates in whom a clavicular fracture was present, this was always seen ipsilateral to the rib fractures.

Discovery of rib fractures in neonates, as in all young children, is highly suspicious for NAI. Most of these fractures involve the posteromedial rib at or near the costovertebral junction. In a study of 63 posterior rib fractures in 31 infants with inflicted skeletal injury, 87% of the fractures occurred near the costochondral junction [30]. The mechanism is anteroposterior thoracic compression, involving both posterior displacement of the sternum and anterior displacement of the vertebrae as occurs in “two-thumb encircling hand” compression [31]. In particular, the anterior displacement of the vertebrae causes excessive leverage of the posteromedial ribs over the transverse processes of the vertebrae. In macrosomic neonates during labour contractions, passage through the relatively narrow birth canal, additional rotational forces and leverage over the pubic symphysis will exert circumferential forces as encountered during bimanual compression, but selective anterior displacement of the vertebra, as in NAI, does not seem likely. This may be an explanation for the dominance of mid-posterior over posteromedial fractures in patients with birth-related rib fractures. Relative fixation of one side of the thorax during labour provides a mechanical advantage to the other side, resulting in an asymmetrical fracture pattern, as in most patients with birth-related rib fractures (Table 1). The ipsilateral clavicular fractures can also be explained by this mechanism.

In cases of neonatal rib fractures, underlying disorders influencing bone development and strength should be analysed. The most important disorder that should be ruled out is osteogenesis imperfecta (OI). In general, this diagnosis will be readily made in neonates presenting with multiple fractures. It is important to bear in mind that in children with OI, without other apparent radiological abnormalities, posterior rib fractures are rarely encountered [32]. In severe cases, OI will lead to intrauterine death or death soon after birth. Rickets of prematurity has been reported to cause rib fractures in premature neonates [33–35]. Other rare causes such as hypocalciuric hypocalcaemia and hyperparathyroidism have been described as a cause of rib fractures [36, 37]. In all cases of neonatal rib fractures it is mandatory to exclude metabolic diseases by means of laboratory studies that include phosphorus, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, parathormone and vitamin D levels.

In extremely rare cases, external force exerted on the neonate during physiotherapy or cardiopulmonary resuscitation have been reported to cause rib fractures, although the latter tends to lead to anterior rib fractures at the costochondral junction [38–40]. Maternal factors such as the use of medication should also be kept in mind. There is a report of rib fractures occurring in neonates born to women who used magnesium sulphate during pregnancy [41].

As described in this case report, rib fractures in neonates can also be related to birth trauma.

References

Carty H (1997) Non-accidental injury: a review of the radiology. Eur Radiol 7:1365–1376

Kleinman PK (1990) Diagnostic imaging in infant abuse. AJR 155:703–712

Barsness KA, Cha ES, Bensard DD et al (2003) The positive predictive value of rib fractures as an indicator of nonaccidental trauma in children. J Trauma 54:1107–1110

Barry PW, Hocking MD (1993) Infant rib fracture – birth trauma or non-accidental injury. Arch Dis Child 68:250

Bulloch B, Schubert CJ, Brophy PD et al (2000) Cause and clinical characteristics of rib fractures in infants. Pediatrics 105:E48

Durani Y, DePiero AD (2006) Images in emergency medicine. Fracture of left clavicle and left posterior rib due to birth trauma. Ann Emerg Med 47:210–215

Hartmann RW Jr (1997) Radiological case of the month. Rib fractures produced by birth trauma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 151:947–948

Kleinman PK, Marks SC Jr, Nimkin K et al (1996) Rib fractures in 31 abused infants: postmortem radiologic-histopathologic study. Radiology 200:807–810

Rizzolo PJ, Coleman PR (1989) Neonatal rib fracture: birth trauma or child abuse? J Fam Pract 29:561–563

Thomas PS (1977) Rib fractures in infancy. Ann Radiol (Paris) 20:115–122

Ibáñez Godoy I, Mora Navarro D, Delgado Rioja MA et al (2003) Isolated obstetric costal fractures. An Pediatr (Barc) 58:612

Landman L, Homburg R, Sirota L et al (1986) Rib fractures as a cause of immediate neonatal tachypnea. Eur J Pediatr 144:487–488

Caird MS, Reddy S, Ganley TJ et al (2005) Cervical spine fracture-dislocation birth injury: prevention, recognition, and implications for the orthopaedic surgeon. J Pediatr Orthop 25:484–486

Papp S, Dhaliwal G, Davies G (2004) Fetal femur fracture and external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol 104:1154–1156

Thompson KA, Satin AJ, Gherman RB (2003) Spiral fracture of the radius: an unusual case of shoulder dystocia-associated morbidity. Obstet Gynecol 102:36–38

Hickey K, McKenna P (1996) Skull fracture caused by vacuum extraction. Obstet Gynecol 88:671–673

Heise RH, Srivatsa PJ, Karsell PR (1996) Spontaneous intrauterine linear skull fracture: a rare complication of spontaneous vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol 87:851–854

Vasa R, Kim MR (1990) Fracture of the femur at cesarean section: case report and review of literature. Am J Perinatol 7:46–48

Kaplan M, Dollberg M, Wajntraub G (1987) Fractured long bones in a term infant delivered by cesarian section. Pediatr Radiol 17:256–257

Eliahou R, Simanovsky N, Hiller N et al (2006) Fracture-separation of the distal femoral epiphysis in a premature neonate. J Ultrasound Med 25:1603–1605

Lysack JT, Soboleski D (2003) Classic metaphyseal lesion following external cephalic version and cesarean section. Pediatr Radiol 33:422–424

Akbas H, Keskin M, Guneren E (2003) Obstetric mandibular fracture during episiotomy in vaginal delivery. Ann Plast Surg 50:440–441

Groenendaal F, Hukkelhoven C (2007) Fractures in full-term neonates. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 151:424

Alexander JM, Leveno KJ, Hauth J et al (2006) Fetal injury associated with cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 108:885–890

Gudmundsson S, Henningsson AC, Lindqvist P (2005) Correlation of birth injury with maternal height and birthweight. BJOG 112:764–767

Rubin A (1964) Birth injuries: incidence, mechanisms and end results. Obstet Gynecol 23:218–221

Levine MG, Holroyde J, Woods JR Jr et al (1984) Birth trauma: incidence and predisposing factors. Obstet Gynecol 63:792–795

Bhat BV, Kumar A, Oumachigui A (1994) Bone injuries during delivery. Indian J Pediatr 61:401–405

Nadas S, Gudinchet F, Capasso P, Reinberg O (1993) Predisposing factors in obstetrical fractures. Skeletal Radiol 22:195–198

Kleinman PK, Marks SC Jr, Richmond JM et al (1995) Inflicted skeletal injury: a postmortem radiologic-histopathologic study in 31 infants. AJR 165:647–650

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (2006) The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus on science with treatment recommendations for pediatric and neonatal patients: pediatric basic and advanced life support. Pediatrics 117:e955–e977

Lachman RS, Krakow D, Kleinman PK (1998) Differential diagnosis II: osteogenesis imperfecta. In: Kleinman PK (ed) Diagnostic imaging of child abuse, 2nd edn. Mosby, St. Louis, pp 197–213

Dabezies EJ, Warren PD (1997) Fractures in very low birth weight infants with rickets. Clin Orthop Relat Res 335:233–239

Geggel RL, Pereira GR, Spackman TJ (1978) Fractured ribs: unusual presentation of rickets in premature infants. J Pediatr 93:680–682

Keipert JA (1970) Rickets with multiple fractures in a premature infant. Med J Aust 1:672–675

Nguyen VC, Sennott WM, Knox GS (1974) Neonatal hyperparathyroidism. Radiology 112:175–176

Nyweide K, Feldman KW, Gunther DF et al (2006) Hypocalciuric hypercalcemia presenting as neonatal rib fractures: a newly described mutation of the calcium-sensing receptor gene. Pediatr Emerg Care 22:722–724

Chalumeau M, Foix-L’Helias L, Scheinmann P et al (2002) Rib fractures after chest physiotherapy for bronchiolitis or pneumonia in infants. Pediatr Radiol 32:644–647

Clouse JR, Lantz PE (2008) Posterior rib fractures in infants associated with cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Presented at the American Academy of Forensic Sciences 60th Annual Meeting, 18–23 February 2008, Washington DC

Betz P, Liebhardt E (1994) Rib fractures in children – resuscitation or child abuse? Int J Legal Med 106:215–218

Kaplan W, Haymond MW, McKay S et al (2006) Osteopenic effects of MgSO4 in multiple pregnancies. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 19:1225–1230

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Rijn, R.R., Bilo, R.A.C. & Robben, S.G.F. Birth-related mid-posterior rib fractures in neonates: a report of three cases (and a possible fourth case) and a review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol 39, 30–34 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-008-1035-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-008-1035-2