Abstract

Cutis verticis gyrata (CVG) is a skin condition characterized by thick folds and deep furrows, resembling a cortical gyral pattern. There is a recognized but rare association with Noonan syndrome. We report the antenatal imaging, including three-dimensional surface-rendered sonography and MRI, of a fetus with CVG who was subsequently diagnosed with Noonan syndrome. The case illustrates the antenatal appearances of congenital CVG and the potential yield of antenatal imaging in excluding a major central nervous system anomaly. This is important because without prior knowledge of this condition and its imaging characteristics, it is possible to get a false impression of an underlying skull defect on mid-trimester imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Noonan syndrome is a well-recognized entity characterized by multisystem abnormalities including craniofacial dysmorphism, webbing or short neck, cardiac abnormalities, lymphatic vessel dysplasia and cryptorchidism. There are frequently also postnatal feeding difficulties, short stature and failure to thrive in infancy.

Cutis verticis gyrata (CVG) is a descriptive term for a condition of the scalp featuring thick folds and deep furrows resembling a cortical gyral pattern. CVG is a rare condition, but congenital forms have been reported to be associated with both Noonan syndrome [1–3] and Turner syndrome [4, 5]. One mechanism that has been proposed to explain the phenomenon of CVG is that it occurs secondary to over-distension by lymphoedema that then resolves [4, 5]. A similar mechanism is thought to be responsible for some of the phenotypic characteristics, including nuchal webbing, seen in patients with Turner syndrome. We describe an infant with CVG and Noonan syndrome who presented with abnormal antenatal imaging that gives further insight into the development of CVG.

Case report

The mother was a healthy 28-year-old New Zealand European. She was gravida 2, para 1 with a history of miscarriage 2 years previously. She was blood group O positive with no abnormal antibodies and rubella-immune, and had negative serology for syphilis and hepatitis B.

The pregnancy was complicated by a number of abnormal findings on antenatal US. The first abnormality was detected at 19 weeks’ gestation when US identified a large, thin-walled cystic lesion measuring 5.5 cm, arising from the frontal region of the fetal head. A 1.2-cm apparent defect was identified in the frontal bone (Fig. 1) and the lesion was interpreted as a cephalocele. At the time, head growth measurements were normal for gestational age. Additional findings included a two-vessel cord and nuchal oedema with a cystic hygroma (Fig. 2). Fetal echocardiography done at 20 weeks’ gestation showed a normal heart.

Transverse US image through the fetal head at nearly 20 weeks’ gestation shows a large, apparently simple cystic structure arising from the frontal region. There is an apparent bony defect (between arrowheads) in the anterior skull which is thought to be secondary to the metopic suture and ultrasound beam dropout. The coronal sutures are identified (arrows)

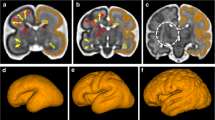

At 22 weeks’ gestation, MRI confirmed a right-sided cystic structure protruding above the level of the orbits (Fig. 3). However, the skull defect was not identified on this or any subsequent imaging and the underlying brain appeared to be normally developed for gestational age except for a mildly enlarged posterior horn of the lateral ventricle. At 22 weeks’ gestation US revealed nuchal oedema bilaterally and a biparietal diameter greater than the 95th centile. At 24 weeks’ gestation the cystic lesion had become thick-walled with an undulating outer contour. Internal septations had developed and progressed over subsequent scans (Fig. 4). The subarachnoid spaces were prominent and the lateral ventricles were mildly dilated. The skull defect was no longer visible.

Selected T2-W MR images at 22 weeks’ gestation. a Midline sagittal image shows the cyst anteriorly (short arrow); nuchal oedema (block arrow) as well as a two-vessel cord (arrowhead) are noted. b Axial image shows the anterior and right-sided cyst with prominent subarachnoid spaces and posterior horn of the lateral ventricle. There was no identifiable bony defect or connection to intracranial structures. c Axial image shows normal brain anatomy

Three-dimensional (3-D) images of the fetal face were obtained at the mother’s request at 27 weeks’ gestation (Fig. 5). By 29 weeks’ gestation there was evidence of polyhydramnios and hydrops fetalis. Lateral ventriculomegaly was present with bilateral pleural effusions, as well as a small pericardial effusion. The frontal cyst was unchanged in size.

A male infant was born at 30 weeks’ gestation via caesarean section for transverse lie, after spontaneous onset of labour. His weight was 1,995 g (96th centile), length was 41.5 cm (64th centile) and his head circumference was 31.6 cm (99th centile). At birth he was hydropic with nuchal webbing, bilateral cryptorchidism, hepatomegaly and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Chromosomes were normal male, 46XY. Postnatal imaging included skull radiographs (Fig. 6) and US of the frontal region (Fig. 7). The skull and cranial sutures underlying the lesion were intact and the cyst had partly collapsed showing a gyriform contour. Cerebral ultrasound scan was normal except for increased subarachnoid fluid spaces. The clinical appearance of the CVG is shown in Fig. 8.

The postnatal course was complicated by a right pleural effusion that was drained soon after birth. In addition, severe bilateral ventricular hypertrophy and mild left ventricular outflow tract obstruction were seen on an early echocardiogram. This progressed despite treatment with propanolol. An echocardiogram 2 days prior to his death showed a severe degree of hypertrophy with almost complete obliteration of the left ventricular cavity and severe pulmonary hypertension. He died at 53 days of age of chronic lung disease and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Discussion

It has been proposed that congenital CVG is a manifestation of previous lymphatic abnormality [4, 5]. The literature on Noonan syndrome reports a strong association with lymphatic abnormality [6, 7]. This may take the form of generalized or localized lymphoedema due to undefined dysplasia of lymphatic vessels. Manifestations can occur at different times from the antenatal period through to adulthood [6]. Pleural effusion and, in more severe cases, hydrops are common around birth, which is the most common time for abnormality to be documented. However, it is also possible for there to be morphological abnormality associated with previous lymphoedema that has resolved, such as webbed neck secondary to cystic hygroma. In the current case there was clear evidence of antenatal generalized lymphatic abnormality with nuchal thickening due to a cystic hygroma seen at 21 weeks’ gestation together with pleural effusion/hydrops at birth and the CVG lesion on the scalp.

Although the association between congenital CVG and Noonan syndrome is rare with only sparse case reports [1–3], the mechanism that has been proposed, i.e. distension by lymphoedema that then resolves, is plausible. Indeed, this is also supported by the fact that it has also been reported to occur with Turner syndrome, which has many similarities in phenotype to Noonan syndrome [4, 5].

The antenatal images presented in this case support the postulated mechanism for congenital CVG being localized lymphoedema of the scalp. It is hypothesized that lack of connection between the venous and lymphatic systems leads to fluid collections resulting in cystic hygromas and hydrops [3]. Several authors have hypothesized that in utero compression may fix lymphoedematous skin into the folds that manifest clinically as CVG [3, 5]. In our patient the antenatal imaging clearly illustrated the progression of the fluid-filled cystic mass seen on the 19-week scan (Fig. 1) evolving into the septated cyst, the lesion seen on 3-D imaging (Fig. 5) and then finally at delivery taking on the clinical appearance of CVG (Fig. 8).

In addition, the case highlights the antenatal appearance of congenital CVG and the yield of antenatal imaging in excluding a major central nervous system anomaly. The authors have also encountered a diagnostic pitfall with the false impression of an underlying skull defect on mid-trimester imaging. This finding, thought to be secondary to a combination of the metopic suture and ultrasound drop-out artefact, resulted in an initial incorrect diagnosis of a frontal cephalocele. This pitfall was also encountered in a previously reported case of isolated CVG [8].

The diagnosis of CVG is possible on routine antenatal US [6], but considerable further information may be obtained using other imaging modalities, such as 3-D US and MRI. This is extremely useful for counselling families.

A brief description of some aspects of this case is included in a discussion of the classification system of CVG [9].

References

Lacombe D, Taieb A, Masson P et al (1991) Neonatal Noonan syndrome with molluscoid cutaneous excess over the scalp. Genet Couns 2:249–253

Masson P, Fayon M, Lamireau T et al (1993) Unusual form of Noonan syndrome: neonatal multi-organ involvement with chylothorax and nevoid cutis verticis gyrata. Pediatrie 48:59–62

Fox L, Geyer A, Anyane-Yeboa K et al (2005) Cutis verticis gyrata in a patient with Noonan syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol 22:142–146

Debeer A, Steenkiste E, Devriendt K et al (2005) Scalp skin lesion in Turner syndrome: more than lymphoedema? Clin Dysmorphol 14:149–150

Larralde M, Gardner S, Torrado M et al (1998) Lymphedema as a postulated cause of cutis verticis gyrata in Turner syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol 15:18–22

Witt D, Hoyme E, Zonana J et al (1987) Lymphedema in Noonan syndrome: clues to pathogenesis and parental diagnosis and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet 27:841–856

Nisbet DL, Griffin DR, Chitty LS (1999) Prenatal features of Noonan syndrome. Prenat Diagn 19:642–647

Nas T, Biri A, Gursoy K et al (2005) Prenatal ultrasonographic appearance of isolated cutis verticis gyrata. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 26:97–98

Larsen F, Birchall N (2007) Cutis verticis gyrata: three cases with different aetiologies that demonstrate the classification system. Australas J Dermatol 48:91–94

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kennedy, A., Perry, D. & Battin, M. Antenatal imaging of cutis verticis gyrata. Pediatr Radiol 38, 583–587 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-008-0747-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-008-0747-7