Abstract

Background: Assessment of appendicitis during a weeknight or weekend shift (after-hours period, AHP) might be more costly and less effective than its assessment on a weekday shift (standard hours period, SHP) because of increased costs (staff premium fees) and perforation risk (longer delays and less experience of fellows). Objectives: The objectives were to compare the costs and effectiveness of assessing children with suspected appendicitis who required a laparotomy and had US or CT after-hours with those of assessing children during standard hours, and to evaluate the importance of diagnostic imaging (DI) within the overall costs. Materials and methods: We retrospectively microcosted resource use within six areas of a tertiary hospital (emergency [ED], diagnostic imaging (DI), surgery, wards, transport, and pathology) in a tertiary hospital. About 41 children (1.8–17 years) in the AHP and 35 (2.9–16 years) in the SHP were evaluated. Work shift effectiveness was measured with a histological score that assessed the severity of appendicitis (non-perforated appendicitis: scores 1–3; perforated appendicitis: score 4). Results: The SHP was less costly and more effective regardless of whether the calculation included US or CT costs only. For a salary-based fee schedule, US$733 were saved per case of perforated appendicitis averted in the SHP. For a fee-for-service payment schedule, $847 were saved. Within the overall budget, the highest costs were those incurred on the ward for both shifts. The average cost per patient in DI ranged from 2 to 5% of the total costs in both shifts. Most perforation cases were found in the AHP (31.7%, AHP vs. 17.1%, SHP), which resulted in higher ward costs for patients in the AHP. Conclusion: A higher proportion of severe cases was seen in the AHP, which led to its higher costs. As a result, the SHP dominated the AHP, being less costly and more effective regardless of the fee schedule applied. The DI costs contributed little to the overall cost of the assessment of appendicitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lund DP, Murphy EU (1994) Management of perforated appendicitis in children: a decade of aggressive treatment. J Pediatr Surg 29:1130–1134

Crady SK, Jones JS, Wyn T, et al (1993) Clinical validity of ultrasound in children with suspected appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med 22:1125–1129

Adolph VR, Falterman KW (1996) Appendicitis in children in the managed care era. J Pediatr Surg 31:1035–1037

Wagner JM, McKinney WP, Carpenter JL (1996) Does the patient have appendicitis? JAMA 276:1589–1594

Wilcox RT, Traverso LW (1997) Have the evaluation and treatment of acute appendicitis changed with new technology? Surg Clin North Am 77:1355–1370

Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, et al (1990) The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 132:910–925

Bell CM, Redelmeier DA (2001) Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med 345:663–668

Mangold WD (1981) Neonatal mortality by the day of the week in the 1974–1975. Arkansas live birth cohort. Am J Public Health 71:601–605

Hendry RA (1981) The weekend—a dangerous time to be born? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 88:1200–1203

Pohl D, Golub R, Schwartz GE, et al (1998) Appendiceal ultrasonography performed by nonradiologists: does it help in the diagnostic process? J Ultrasound Med 17:217–221

Clark AP (2002) Hospital deaths and weekend admissions—how do we leap across a chiasm? Clin Nurs Spec 16:91–92

Barnett MJ, Kaboli PJ, Sirio CA, et al (2002) Day of the week of intensive care admission and patient outcomes. Med Care 40:530–539

Lowe LH, Draud KS, Hernanz-Schulman M, et al (2001) Nonenhanced limited CT in children suspected of having appendicitis: prospective comparison of attending and resident interpretations. Radiology 221:755–759

Sunil K, Sundeep J (2004) Treatment of appendiceal mass: prospective, randomized clinical trial. Indian J Gastroenterol 23:165–167

Nitecki S, Assalia A, Schein M (1993) Contemporary management of the appendiceal mass. Br J Surg 80:18–20

Integrated metadata base from Stats Canada. Available at: http://datacentre.chass.utoronto.ca/cansim/. Accessed October 28, 2004

Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, et al (1996) Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford University Press, New York

Crawford JM (1994) The gastrointestinal system. In: Cotran RS, Kumar V, Robbins SL (eds) Pathologic basis of disease, 5th edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 822–823

Liem YS, Kock MC, Ijzermans JNM, et al (2003) Living renal donors: optimizing the imaging strategy—decision-effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analysis. Radiology 226:53–62

Roosevelt GE, Reynolds SL (1998) Does the use of ultrasonography improve the outcome of children with appendicitis? Acad Emerg Med 5:1071–1075

Hamilton J, Rao PM, Wagner JM, et al (1998) Appendicitis: unmasking the great masquerader. Patient Care 32:140–156

Rao PM, Rhea JT, Rattner DW, et al (1999) Introduction of appendiceal CT. Impact on negative appendectomy and appendiceal perforation rates. Ann Surg 229:344–349

Ujiki MB, Murayama K, Cribbins J, et al (2002) CT scan in the management of acute appendicitis. J Surg Res 105:119–122

Moore JD Jr (1996) Hospital saves by working weekends. Mod Healthc 26:82–84

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Rita Pyle (Information Services), Lufti Assad (Emergency), Brian Mackie (Finances), Amy Judson (Pharmacy), Linda Whyte (General Surgery), Charles Smith and Lois Lines (Pathology and Laboratory Medicine), Guila Bendavid and Albert Aziza (Diagnostic Imaging), Christine van Klaveren (Public Affairs), Ian Farmer (Support Services), and Debi S. Senger (Health Records), staff at the Hospital for Sick Children, for providing data crucial to this analysis. We also thank the Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, Clinical Epidemiology, University of Toronto for support during this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: sources of patient identification

Study subjects were identified from the hospital database [Datawarehouse, surgery, imaging guided therapy (IGT), pharmacy, and pathology databases] by procedure category codes and descriptors of surgery for appendicitis (other appendectomy, laparoscopic appendectomy, other operation on appendix, drainage of appendiceal abscess). Data were also collected through Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS), individual patient charts, and communication with various departments at our institution.

Appendix 2: conversion of Canadian dollars to US dollars

The US currencies were obtained using the following formula: $ Y in 2001 Canadian dollars = $ Y×0.75×1.07 in 2004 US dollars, where 0.75 represented the conversion factor and 1.07, the corresponding inflation factor of US dollars adjusted for the growth in the US consumer price index from 2001 to 2004, which was about 7% [16].

Appendix 3: costing

In the emergency department the categories assessed were hospital charges for the maintenance of the patient in this department, radiographic and laboratory examinations, and professional fees for the clinician staff and general surgery fellow. In the DI department, the resources assessed were professional fees for fellows (for US in the AHP and for CT in both shifts), US technologists (for SHP), CT technologists (for both shifts), radiology staff (for both shifts), CT nurse (for both shifts); sedative medication for CT; oral and intravenous CT contrast agents; prophylactic medication for intravenous administration of CT contrast agents; office supplies; overhead costs for the US and CT suites; and equipment maintenance (US, CT scanners, and PACS units). The overhead costs for DI included rental for the rooms used for imaging, electric power, and laundry. The cost of items included in a patient’s hospitalization on the ward included the daily hotel cost, laboratory tests, imaging examinations and interventional procedures, intravenous fluids, medications administered, and professional (general surgery staff and nurses) and technical reimbursements. Other departments’ detailed costs are available from the authors. Professional fees for fellows performing one US procedure assumed 1 h per procedure, including review and dictation. Costing was done according to the fees obtained from our institution’s salary-based fee schedule.

Appendix 4: sensitivity analysis

Method

Testing the sensitivity of the ICERs to variations in DI department costs was done by calculating US and CT costs separately in the analysis.

Results

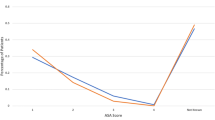

Regardless of whether the calculation included individualized US or CT costs as part of the costs for the DI department, the SHP more inexpensively and more effectively avoided perforation of the appendix than the AHP shift. If US costs only were used, the application of the AHP shift would enable a saving of $681 per case of perforated appendicitis averted; the use of CT costs only, a saving of $654. The difference in the ICERs obtained with the incorporation of costs from both US and CT and with US only was $51, and from both imaging modalities and with CT only was $79.

Discussion

The results of our sensitivity analysis showed that the individualized incorporation of US or CT costs in the analysis of the ICER in our study indicates negligible variations in the incremental savings, confirming results from another study [25]. The lower incremental savings obtained with the inclusion of US or CT costs only rather than with inclusion of both indicates that the use of both US and CT improves the allocation of financial resources in the department.

Conclusion

The use of US or CT for the assessment of children with clinically suspected appendicitis did not change the ICER significantly.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doria, A.S., Amernic, H., Dick, P. et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of weekday and weeknight or weekend shifts for assessment of appendicitis. Pediatr Radiol 35, 1186–1195 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-005-1570-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-005-1570-z