Abstract

PCMs (phase change materials) applied in heat storage technology are on the one hand characterised by relatively large specific heat capacity, and on the other hand by relatively low thermal conductivity (e.g. 0.2 W·m−1·K−1) for paraffin), which prolongs the charging/discharging cycles of heat accumulators based on such materials. In order to improve the heat transfer within PCMs, spatially shaped pin-fin metal alloy structures are being developed that have been immersed in the PCM material. Pin-fin metallic structures can be manufactured via investment casting technology. The 3D structures produced using this technique can be modified and adjusted in order to improve the heat transfer parameters (heat conductivity, specific heat transfer area). For this study, complex metal alloy pin-fin structures were immersed in paraffin, and an experimental test stand was built in order to examine the heat transfer characteristics of composite PCMs with pin-fin metal structures. Multiple heating/cooling cycles confirmed the enhanced transfer of heat inside the heat storage unit and allowed us to ascertain the decreased temperature gradient within the heat accumulator. The heat transfer phenomenon was simulated to show heating and melting course nearby metal inserts and confirm the beneficial influence of the applied pin-fin geometry, that can be further optimized. The thermal behaviour of the PCM, tested with DSC and TGA analysis, was used as an input for the simulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Phase change materials (PCMs) can be applied in heat storage systems, e.g. charging from heat sources, absorbing excess energy in the form of latent heat of fusion, and finally supporting many industrial processes in which liquids characterised by relatively high temperatures are needed. Unfortunately, their thermal conductivities are low (e.g. 0.2 W·m−1·K−1 for paraffin, 0.4 W·m−1·K−1 for KNO3, 0.5–0.6 W·m−1·K−1 for NaNO3), which limits their application as functional materials in heat accumulators. It should be emphasised that sophisticated technological solutions or advanced materials for improving heat transfer in PCMs are limited in their industrial application due to economic reasons. Thus, the improvement of design of heat storage units seems to be a promising way of enhancing the heat transfer while preserving economic feasibility on large scale. In order to improve heat transfer performance within PCMs, elements in the form of preforms from graphite fibres, capsules, or silica catalysts [1,2,3] or differently shaped metal structures can be immersed in the PCM material [4,5,6,7]. Among them, a special group of pin-fin structures can be distinguished and used as heat exchangers in thermal energy storage systems. Moreover, pin-fin elements are readily used not only for heating but also for cooling applications, such as for components used in electronics. They can be applied in the form of compact heat exchangers due to their high heat transfer surface area per unit volume, which alters the heat flow and enhances mixing and fluid dynamics. Therefore, any optimisation procedure that could lead to desirable results in terms of multidirectional heat transfer would be highly beneficial for their reliable performance.

Numerous shapes of cross-sections of fins are described in the literature, e.g. drop-shaped or circular [8,9,10,11,12]. Various Reynolds numbers and geometrical configurations of pin-fins were considered by Saha and Acharya [13] in a numerical study that was carried out to analyse the unsteady three-dimensional flow and heat transfer in a parallel-plate channel of a heat exchanger with in-line arrays of periodically mounted pins of rectangular cross-section. In the paper presented by Rao et al. [14] a comparative experimental and numerical study was conducted on the heat transfer of pin-fin and pin-fin-dimple structures. A solution in which pin-fins were alternately located with dimples was found to be more efficient than the one composed only of pin-fin columns. Sahiti et al. [15] elaborated the heat transfer and pressure-drop characteristics of a double-pipe pin-fin heat exchanger.

Metallic 3D structures can be manufactured via investment casting technology, modified, and adjusted to increase the heat transfer parameters of the PCM-metal alloy insert arrangement, such as thermal conductivity and specific heat transfer area. Such important factors as mechanical and fatigue properties of the metal alloy were also considered as a result of the previous work performed by Naplocha et al. [7]. In order to attain the best casting quality, the essential requirements concerning the process parameters were indicated by Nadolski et al. [16], as follows:

lack of reaction between the chosen casting alloy and the ceramic mould,

sufficient strength and gas permeability of the ceramic mould,

facilitated cleaning of the casting surface to remove the remnants of ceramic material.

According to the work of Cholewa et al. [17], which was supported by simulation of the mould-filling process for complex castings, metallostatic pressure has a crucial effect on the quality of filling of narrow mould channels. Gas permeability can be improved by subjecting ceramic moulds to higher temperatures during the burn-out cycle [18]. The last, but difficult technological step is the precise cleaning of the casting to remove the remnants of ceramic material after mechanical removal of the ceramic mould. Facilitation methods focused on the intensification of the common washing out process can incorporate the usage of ultrasonic cleaners or different additives for the ceramic slurry, such as sand or polymer-modified binders [19].

In the presented paper, a pin-fin metal alloy structure based on a honeycomb pattern, in which pins were located in the corners of the hexagons, was immersed in paraffin, and an experimental test stand was built to study the heat transfer characteristics of the composite PCM. The solution based on pin-fin spatial structure is hereby proposed as an alternative to the previously studied open-cellular metal foams of 10 PPI (pores per inch) described in earlier works of the authors [6, 7]. Although the sizes of the cavities separating pins are larger than in the case of porous foams, the mechanism of heat transfer is comparable. The main aim of the presented study is to accomplish a quantitative evaluation of the performance of thermal energy accumulators based on PCMs, combined with immersed spatial metallic structures. The completed simulation consisted of transferring the geometry of the laboratory heat storage unit into a three-dimensional numerical model, as well as the setup of domains, selection of physics models, and the setup in Comsol Multiphysics software.

2 Materials and methods

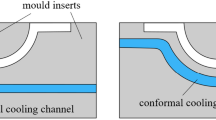

The manufacturing process of the 3D spatial structures (pin-fin structure) from Al-Si eutectic alloy EN AC 44200 (10.0–13.5% Si, 0.4% Fe, 0.05% Cu, 0.4% Mn, 0.1% Zn, 0.15%, Al-rest), was based on investment casting and consisted of the following stages:

- 1

Pattern design.

- 2

Preparation of the ceramic mould and subsequent heat-treatment leading to burn-out of the pattern.

- 3

Supported gravity casting in an autoclave with Al-Si alloy characterised by the thermal conductivity of 130–170 W·m−1·K−1.

- 4

Removal of the mould and rinsing to remove remnants of the ceramic material from the casting.

Ceramic slurry for the moulding was prepared from Gold Star XXX Investment material, which was composed of matrix - quartz <50% + cristobalite <50%, and binder - CaSO4. In accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, the mould was dried at a temperature of 150 °C for 3 h and then at 370 °C for 2 h. Then the temperature was raised to the temperature at which combustion and gasification of the polymer pattern took place. Subsequently, the liquid metal was cast into the remaining voids.

The flow of the liquid metal through the mould channels can be compared with the infiltration of narrow cavities. Therefore, some critical process parameters such as the cast temperature and metallostatic pressure had to be analysed and determined experimentally. For instance, excessively high metallostatic pressure can lead to the leakage of metal through microcracks in the mould. The temperature of the ceramic mould should be similar to the temperature of the molten Al alloy so that the metal is able flow within the relatively thin channels. Figure 1a presents the manufactured cast element with the fins in the form of pins. After cutting off the gating system this spatial metal structure was located in the centre of the isolated PCM accumulator and fully immersed in paraffin. The level of the PCM was consistent with the height of the 3D structure (40 mm), characterised by the shape of a regular hexagonal array (“honeycomb pattern”) with pin-fin columns attached to each corner of the hexagons. The size of the sides of the hexagons was 11.15 mm, and the base was composed of three triple-hexagon rows and two quadruple hexagons, so the spatial structure contained a total of 17 hexagons.

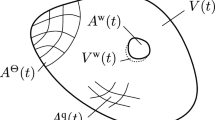

Subsequently, the above-described heat accumulator was subjected to numerous charging/discharging cycles. The temperature gradient in the function of time was controlled with the use of three thermocouples located at the bottom (at a height of 1 mm), the top (at a height of 36 mm), and the centre (at a height of 18 mm) of the accumulator. Charging and discharging cycles of the heat accumulator, designed as a cylindrical chamber with a diameter of 110 mm, was performed by means of a heated plate (195–200 °C) as the heat source, in order to achieve semi-directional heat flux in the direction of the height of the accumulator. The experimental data were collected by numerical method using an Adam 4018 type adapter with eight channels. Charging and discharging times were respectively 1 h and 7 h. The first trials established the performance of the accumulator filled only with the PCM material, and the next were performed with application of the composite PCM with the designed and paraffin-immersed pin-fin metal alloy structure. A test of whether this solution gave improved outcomes was performed by applying a numerical model of a laboratory heat storage unit. This model consisted of two main domains: a PCM domain and a metal domain (highlighted in Fig. 1b).

The described approach and methodologies were chosen to conduct simulations of the heat transfer in the heat storage unit, specifically in the phase change material, during heating. The material properties and parameters applied in the model are shown in Table 1. The numerical simulation was performed with the use of Finite Element Method in Comsol Multiphysics software, which was also used by Keshari et al. [21] to elaborate a finned tube heat exchanger assembly made of copper pin-fins and tubes.

The geometry of the heat storage unit model is presented in Fig. 1b. The model reproduces the geometry of the heat storage unit used in the experiment.

The heat storage unit consists of two main domains: a PCM domain and a metal domain (highlighted in Fig. 1b). The heat source, in the form of a constant temperature (boundary condition: wall temperature of 195 °C), is located at the bottom part of the base (Fig. 1). The following Eq. (1) represents the boundary condition:

where,

Twall – heat source temperature.

The PCM domain and the metal domain were matched to the heat transfer module. The boundary condition for other walls involve the heat flux with a convective heat transfer coefficient of 20 W·m−2·K−1) and an ambient temperature of 25 °C, which represents the external conditions. This is represented by Eq. 2:

where:

q – heat flux,

h – convective heat transfer coefficient,

Tamb – ambient temperature.

The model used in the simulations assumed that the heat transfer mechanism in PCM is conduction. Such an approach has previously been successfully applied in similar simulations, as presented in [22]. The expression for the heat transfer is represented by Eq. 3:

where:

ρ – density of the PCM.

Cp – specific heat of PCM, (J·kg−1·K−1).

k – thermal conductivity of the PCM.

Among two numerical methods applicable to solve the phase change process problem (enthalpy method and effective heat capacity method), the effective heat capacity method was used. The effective (total) heat capacity of the PCM in a temperature range of T0 – Tf, consists of solid state heat capacity, phase change enthalpy (latent heat) and liquid state heat capacity, which is expressed by Eq. 4:

where:

T0 – initial temperature of the PCM.

Tm – temperature of PCM phase change.

m – mass of PCM.

ΔHm – phase change enthalpy per unit mass, (J·kg−1).

Tf – final temperature of the PCM.

Due to the assumption that the heat capacity of the PCM for both solid and liquid state is constant within the considered temperature range, and that in real conditions the phase change material occurs within a specific temperature range, the expression may be modified to the form represented by Eq. 5. As a result, the heat capacity of the PCM for the entire temperature range can be expressed by a piecewise function (Table 1).

where.

Tm,i – temperature of PCM phase change start.

Tm,f – temperature of PCM phase change end.

Cp,solid – specific heat of solid PCM, (J·kg−1·K−1).

Cp,liquid – specific heat of liquid PCM, (J·kg−1·K−1).

ΔHm – phase change enthalpy per unit mass, (J·kg−1).

The mesh consists of tetrahedral elements of minimum size 0.00115 m and maximum size 0.00924 m, the maximum element growth rate is 1.45, the curvature factor is 0.5, and the resolution of the narrow regions is 0.6.

3 Results and discussion

After multiple charge/discharge cycles it can be concluded that the heat transfer parameters of the PCM with the immersed pin-fin metal structure were significantly enhanced. The following benefits were observed in comparison to paraffin alone:

The loading period was shortened,

The maximum temperature was increased,

The temperature gradient within the accumulator was significantly reduced.

Figure 2 shows the temperature/time relationship for the loading/unloading cycle for the accumulator with the RT-82 paraffin as the PCM and the inserted metal structure with fins in the form of pins. The temperature was measured at three points located on the central axis of the accumulator: at heights of 1 mm, 18 mm, and 38 mm above the metal base. The duration of the full loading cycle was eight hours. A comparison of temperature vs time dependences during heating periods for the heat accumulator until the start of melting of PCM within the chamber with the additional metal fins and without them indicates that the metal pin-fin insert significantly increased the heating rate of the PCM-based accumulator (see Fig. 3), and it helped to decrease the temperature difference between the applied measuring points. In the late phase of heating, the curve for sole paraffin exceeds the one with pin-fin structure, what can be explained by the dynamics of melting of the PCM, in particular, formation and movement of non-melted paraffin particles.

The temperature differences between bottom and centre measurement points (temperature difference between h = 1 mm and h = 18 mm) and between bottom and top measurement points (temperature difference between h = 1 mm and h = 36 mm) are shown in Fig. 4. This temperature difference (ΔT) is more than two times lower for the PCM with the pin-fin metal alloy structure than without it. The temperature difference for the heat accumulator with the pin-fin structure is slightly larger than in the accumulator without this structure only once, for height h = 1÷18, shortly after c.a. 40 min. This can be explained by the fact that, due to the higher thermal conductivity of Al alloy, the pins allow fast transferral of a certain amount heat into the upper parts of heat accumulator, temporarily reducing the temperature growth rate at the centre of the accumulator.

Within the range of the presented studies, a numerical model of the laboratory heat storage unit was elaborated in order to conduct simulations of heat transfer within the heat storage unit, in particular in the phase change material during the charging process. Fig. 5 presents a temperature distribution map in a vertical cross-section of the heat storage unit with the Al-Si alloy pin-fin structure together with the phase change isosurface corresponding to the interface between solid and liquid phases after 10 min., 30 min., and 1 h of heating. The isosurface temperature value is 82 °C, which corresponds to the melting point of RT-82 paraffin (melting peak).

As is evident, even after the first 10 min of heating the energy is already transferred to the upper part of the accumulator along with the axis of fins (see Fig. 5). Together with the increasing heating time, the PCM material located near the pins is melting. The interface between solid and liquid paraffin after 1 h of charging indicates that the entire volume of PCM among the pin-fin insert is in the liquid state, although even after 30 min it is in similar stage. Simulated temperature values in three PCM temperature measurement points (1 mm, 18 mm, 36 mm), reproducing the thermocouple locations in the experiment, are presented in Table 2.

Future works should focus on other important factors concerning the detailed parameters of the tested pin-fin structure, such as: increased pin-fin height, change in pin-fin diameter and cross-section, and the influence of the number of pin-fin arrays within the 3D metallic structure. As was reported in the studies of A. K. Saha et al. [13], the energy transfer tends initially to increase with greater pin-fin height up to a certain point, but then it decreases if the distance is too great for heat transfer. Larger diameter of the pins and greater number of pin-fin arrays improve the overall thermal conductivity by creating a larger heat transfer area [20]; on the other hand, this would probably lead to an inadvisable gain in weight of such heat exchangers. All of these issues should be investigated in more advanced studies.

The performed simulations provide insight into the loading process of the PCM-based accumulator in the entire volume of the heat storage unit, with particular attention paid to the influence of the design of the heat storage unit on the melting process. The temperature distribution maps indicate that the vertical columns attached to the base of the heat storage unit greatly enhanced the heat transfer. As a result, the presented heat storage unit design, with the already performed investigations and the intended ones, will help to overcome the problem of low thermal conductivity of paraffin as a PCM.

4 Conclusions

A manufacturing method of cast Al-Si pin-fin structures for improvement of the loading/unloading parameters of heat accumulators with RT-82 paraffin as the PCM was developed. The designed patterns were successfully applied for the investment casting using the replica technique. The performed investigations led to the conclusion that the application of the designed pattern allows the preparation of a ceramic mould suitable for manufacturing Al alloy-based pin-fin structures by investment casting. Moreover, the most crucial parameters affecting metal flow during the casting process were identified as the metallostatic pressure and the temperature of the mould.

The application of metallic 3D structures is one of the most promising solutions for the enhancement of heat transfer in heat storage units. Manufactured pin-fin structures immersed in phase change materials (PCM, paraffin RT-82) were able to improve the heat transfer and efficiency of the heat storage system. Not only were they able to improve the thermal conductivity of the system, but they also shortened the loading time and dramatically decreased the temperature gradient within the accumulator. Heat transfer phenomena can be successfully simulated by a numerical model in order to facilitate the prediction of the overall efficiency of the systems.

References

Zhao CY, Zhou D, Wu ZG (2011) Heat transfer of phase change materials (PCMs) in porous materials. Frontiers Energy 5(2):174–180

Zhao CY, Lu W, Tian Y (2010) Heat transfer enhancement for thermal energy storage using metal foams embedded within phase change materials (PCMs). Sol Energy 84:1402–1412

Zhao CY (2012) Review on thermal transport in high porosity cellular metal foams with open cells. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer55:3618–3632

Nomura T, Okinaka N, Akiyama T (2009) Impregnation of porous material with phase change material for thermal energy storage. Mater Chem Phys 115(2–3):846–850

Aydin D, Casey SP, Riffat S (2015) The latest advancements on thermochemical heat storage systems. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev 41:356–367

Naplocha K, Dmitruk A, Lichota J, Kaczmar J (2016) Enhancement of heat transfer in PCM by cellular Zn-Al structure. Archives Foundry Eng 16:91–94

Naplocha K, Dmitruk A, Kaczmar J, Lichota J, Smykowski D (2017) Effects of cellular metals on the performances and durability of composite heat storage systems. Int J Heat Mass Transf 114:1214–1219

H. Nabati, “Optimal pin-fin heat exchanger surface”, Thesis, 2008

M. Lyall, “Heat transfer from low aspect ratio pin-fins”, Thesis, 2006

Wang F, Zhan J, Wang S (2012) Investigation on flow and heat transfer characteristics in rectangular channel with drop-shaped pin-fins. Propulsion Power Res 1:64–70

Srikanth R, Balaji C (2017) Heat transfer correlations for a composite PCM based 72 pin fin heat sink with discrete heating at the base. INAE Letters 2:65–71

Hasan MI, Tbena HL (2018) Using of phase change materials to enhance the thermal performance of micro channel heat sink. Eng Sci Technol, Int J 21(3):517–526

Saha AK, Acharya S (2003) Parametric study of unsteady flow and heat transfer in a pin-fin heat exchanger. Int J Heat Mass Transf 46:3815–3830

Rao Y, Xu Y, Wan C (2012) An experimental and numerical study of flow and heat transfer in channels with pin fin-dimple and pin fin arrays. Exp Thermal Fluid Sci 38:237–247

Sahiti N, Krasniqi F, Fejzullahu X, Bunjaku J, Muriqi A (2008) Entropy generation minimization of a double-pipe pin fin heat exchanger. Appl Therm Eng 28:2337–2344

Nadolski M, Konopka Z, Łągiewka M, Zyska A (2008) Mechanical properties of investment casting molds reinforced with ceramic fibre. Archives Foundry Eng 8(1):149–152

Cholewa M, Dziuba M, Kondracki M, Suchoń J (2008) Validation studies of temperature distribution and Mold filling process for composite skeleton castings. Archives Foundry Eng 8(1):163–168

Tryteka A, Nawrocki J, Sarek D (2010) Lost wax process – mold properties. Archives Foundry Eng 10(1):427–430

Nadolski M, Konopka Z, Łągiewka M, Zyska A (2008) Examining of slurries and production of molds by spraying method in lost wax technology. Archives Foundry Eng 8(2):107–110

RT-82 Paraffin PCM Data Sheet, https://www.rubitherm.eu/media/products/datasheets/Techdata_-RT82_EN_06082018.PDF, September 2019

Keshari V, Maiya MP (2018) Design and investigation of hydriding alloy based hydrogen storage reactor integrated with a pin fin tube heat exchanger. Int J Hydrog Energy 43:7081–7095

Sciacovelli A, Gagliardi F, Verda V (2015) Maximization of performance of a PCM latent heat storage system with innovative fins. Appl Energy Vol 137(1):707–715

Acknowledgments

The results presented in this paper have been obtained within the project ACCUSOL “Elaboration of the novel cooling/heating system of buildings with the application of photovoltaic cells, solar collectors and heat accumulators” - contract No. ERANet-LAC, No. ELEC2015/T06-0523 (2017-2019) realized within the 7th Framework Program and supported by the National Centre of Science and Development in Warsaw, Poland and the European Commission in Brussels, Belgium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• Pin-fin metal structures were developed via investment casting technology and immersed in the PCM material in order to improve heat transfer within PCM (heat conductivity, specific heat transfer area)

• Performed multiple heating/cooling cycles confirmed the enhanced transfer of heat and allow to ascertain the decreased temperature gradient within the accumulator

• The heat transfer phenomena during heating was simulated with the use of Comsol Multiphysics software

• The thermal behavior of PCM, tested with the DSC and TGA analysis, was used as an input for the simulation

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dmitruk, A., Naplocha, K., Kaczmar, J.W. et al. Pin-fin metal alloy structures enhancing heat transfer in PCM-based heat storage units. Heat Mass Transfer 56, 2265–2271 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00231-020-02861-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00231-020-02861-6