Abstract

The reaction between hypochlorous acid and chlorite ions is the rate limiting step for in situ chlorine dioxide regeneration. The possibility of increasing the speed of this reaction was analyzed by the addition of tertiary amine catalysts in the system at pH 5. Two amines were tested, DABCO (1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane) and its derivative CEM-DABCO (1-carboethoxymethyl-1-azonia-4-aza-bicyclo[2.2.2]octane chloride). The stability of the catalysts in the presence of both reagents and chlorine dioxide was measured, with CEM-DABCO showing to be highly stable with the mentioned chlorine species, whereas DABCO was rapidly degraded by chlorine dioxide. Hence, CEM-DABCO was chosen as a suitable candidate to catalyze the reaction of hypochlorous acid with chlorite ions and it significantly increased the speed of this reaction even at low catalyst dosages. This research opens the door to a faster regeneration of chlorine dioxide and an improved efficiency in chlorine dioxide treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tertiary amines are versatile compounds that can catalyze a wide range of organic (Ammer et al. 2010) and oxidation reactions (Prütz 1998; Huang and Shah 2018). They are versatile catalysts because of their nucleophilic character and their availability to incorporate different functional groups, which may provide higher stability and reactivity (Prütz 1998; Shah et al. 2011; Dodd et al. 2005). Tertiary amines can be used as catalysts in polyurethane production (Sardon et al. 2015), in the Baylis–Hillman reaction, enhancing the generation of new C–C bonds (Basavaiah et al. 2010) and in water treatment. In water treatment, tertiary amines have been shown to boost the degradation of organic contaminants and promote the disinfection of water (Huang and Shah 2018; Basavaiah et al. 2010). It is known that the addition of a tertiary amine such as DABCO (1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane) to hypochlorous acid (\({\text{HOCl}}\)) produces a highly reactive chlorommonium cation (Rosenblatt et al. 1972). This chloroammonium cation can oxidize saturated structures faster than \({\text{HOCl}}\) (Afsahi et al. 2015; Prütz 1998). Hence, many industries could benefit from faster reactions using chloroammonium cations, including energy-intensive pulp bleaching processes. Nevertheless, finding the right structure that would be stable with the chlorine species, and especially with \({\text{HOCl}}\) and chlorine dioxide (\({\text{ClO}}_{2}\)), has proven challenging.

\({\text{HOCl}}\) is a strong oxidant that exists in a pH-dependent equilibrium with chlorine (\({\text{Cl}}_{2}\)) and hypochlorite ion (\({\text{ClO}}^{ - }\)). At pH higher than the pKa (7.6) of HOCl, \({\text{ClO}}^{ - }\) ion is the dominant species, while at pH < 3.5, the presence of \({\text{Cl}}_{2}\) becomes significant. Between these points, HOCl is the most abundant and important species (Gombas et al. 2017). Although HOCl and Cl2 are efficient oxidants, they have been displaced by \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) in some applications because \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) produces lower amounts of organochlorinated compounds than elemental chlorine chemicals (\({\text{Cl}}_{2}\), \({\text{HOCl}}\) and \({\text{ ClO}}^{ - }\)) do (Prütz et al. 2001).

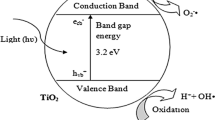

\({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) is a strong oxidant that is widely used in industrial pulp bleaching (Sixta et al. 2006; Gordon and Rosenblatt 2005) and water disinfection (Ye et al. 2019; Benisti 2018). \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) is produced on site because it cannot be stored or transported due to its toxicity and instability. It is usually produced from sodium chlorate (Gordon and Rosenblatt 2005), but it can also be produced from the reaction of sodium chlorite ions and sodium hypochlorite in acidic conditions (Masschelein 1967). More interestingly, chlorine dioxide can be regenerated, meaning that its degradation products can react to reform chlorine dioxide. This is the case in the oxidation of organic phenolic substrates, where chlorine dioxide is reduced to hypochlorous acid (\({\text{HOCl}}\)) and chlorite ions (\({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\)) (Svenson et al. 2006), which react together, forming \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) again. The importance of the reaction of \({\text{HOCl}}\) with \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) derives from its role in the regeneration of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) (Fig. 1), but it may also be the key to a lowered production of organochlorinated compounds. \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) treatments produce a low amount of organochlorinated compounds and it is believed that the small percentage formed is caused by the reactions of the in situ formed \({\text{HOCl}}\) and \({\text{Cl}}_{2}\) (Kolar et al. 1983; Lehtimaa et al. 2010; Gallard and von Gunten 2002). Hence, finding a catalyst that increases the reaction rate of the rate determining step in \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) regeneration is one possibility to push the equilibrium toward higher amounts of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), and therefore to reduce the available \({\text{HOCl}}\) that would be able to react with organic substrates.

Schematic representation of the reaction between HOCl and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) (Tarvo et al. 2009)

Tertiary amines are a clear option to catalyze the regeneration reaction of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\). They are more available and less expensive than transition metals, which yield a high conversion of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) into \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) in acidic conditions (Ringo 1991; Hardee et al. 1983). However, tertiary amines are known to be unstable, especially in the presence of chlorine dioxide. For example, the DABCO chloroammonium cation is unstable by itself, and it undergoes oxidative fragmentation (Brennesein et al. 1965) via carbon–carbon cleavage, producing 1-4-dichloropiperazine, formaldehyde and chloride (Dennis et al. 1967; Fig. 2). A similar oxidative degradation takes place when the DABCO chloroammonium cation is exposed to \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), producing piperazine, ammonia and formaldehyde (Dennis et al. 1967). Previous research has shown that formaldehyde can react with chlorous acid \(\left( {{\text{HClO}}_{2} } \right)\), regenerating \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) (Jiang et al. 2007; Ventorim et al. 2005). However, this reaction also generates undesired formic acid and hydrochloric acid. In summary, the addition of DABCO likely improves the regeneration of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) by the formation of both the chloroammonium cation and of formaldehyde, but it also consumes oxidative power in later degradation stages. Hence, finding a tertiary amine that is stable in aqueous \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) and \({\text{HOCl}}\) is fundamental for their potential use in \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) treatments.

a Formation and degradation of chloroammonium cation from DABCO (Dennis et al. 1967). b Formation of CEM-DABCO chloroammonium cation that does not degrade because it lacks the required free electron pair on nitrogen atom

Recently, an alkyl-substituted DABCO derivative called CM-DABCO was used to generate an active but stable chloroammonium cation in the presence of \({\text{ HOCl}}\) at pH 5 (Afsahi et al. 2019). Hence, alkyl-substituted DABCO derivatives appear to have a larger potential in the catalysis of the chlorine dioxide regeneration reaction. It is expected that CEM-DABCO, just like DABCO, will form a chloroammonium cation with \({\text{HOCl}}\) (Fig. 2). However, the stability of both chloroammonium cations is predicted to differ greatly. The chloroammonium cation of DABCO, is an unstable structure, whereas the chloroammonium cation of CEM-DABCO is expected to be stable. It has no lone pair of electrons due to the alkyl substitution in one of the amino positions, and hence, it will not undergo intramolecular fragmentation.

This article aims to break the old paradigm that tertiary amines are no suitable catalysts in the presence of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) and to study the impact of two tertiary amines in the chlorine dioxide regeneration reaction. The two chosen catalysts are DABCO (as a reference case) and an n-alkyl-substituted DABCO catalyst, hereinafter referred to as CEM-DABCO (1-carboethoxymethyl-1-azonia-4-aza-bicyclo[2.2.2]octane chloride). CEM-DABCO is an intermediate species in CM-DABCO synthesis; hence, it is easier to synthesize. It should display similar stability and catalytic activity to CM-DABCO because it also has one available amino group to form the chloroammonium cation and a low-impact group (alkyl substitution) in the second amino group.

This article will first identify the optimum pH at which the CEM-DABCO chloroammonium cation is formed, before studying the stability of CEM-DABCO in the \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) regeneration system. Finally, it will assess the overall impact of CEM-DABCO in the reaction of \({\text{HOCl}}\) with \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\). The impact of a more stable, but still active, tertiary amine catalyst in the reaction of \({\text{HOCl}}\) with \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) could translate into more efficient \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) treatments with lowered initial chemical charges and energy consumptions. Additionally, it could result in a cleaner treatment, with lowered amounts of organochlorinated compounds produced.

Materials and methods

Materials

Fast kinetics experiments

Commercial sodium hypochlorite (\({\text{NaOCl}}\)) solution and pH 5 buffer solution (citric acid/sodium hydroxide) were purchased from VWR. The \({\text{NaOCl}}\) purity was 7.3% and contained \({\text{ClO}}_{3}^{ - }\) (3.7%) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) (0.2%) as impurities. Chlorine dioxide (\({\text{ClO}}_{2}\)) was produced in a Denzo reactor at 65 °C via the mixing of 1000 g of pure oxalic acid (Merck), 265 g of pure potassium chlorate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1000 ml of distilled water. Solid sodium chlorite (\({\text{NaClO}}_{2}\)) (80%) was also acquired from Sigma-Aldrich. Aqueous solutions of \({\text{NaOCl}}\), \({\text{NaClO}}_{2}\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) were prepared and titrated daily for determination of their active chlorine concentrations. The tertiary amine catalyst, DABCO (1,4-diazabicyclo[2,2,2]octane) (99%), was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

The tertiary amine, CEM-DABCO (1-carboethoxymethyl-1-azonia-4-aza-bicyclo[2.2.2]octane chloride), was synthetized (Engel et al. 2009) by dissolving DABCO (1.222 g) in 20 mL of ethyl acetate, and adding dropwise ethyl chloroacetate on the stirred solution, both purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The solution was left to react for 1 h; the resulting white precipitate was washed 3 times with 30 ml of ethyl acetate and later vacuum-dried to produce CEM-DABCO as a white solid (1.9 g, 74%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δH 1.20 (3H, t, 3JHH = 7.2, COOCH2CH3); 3.16 [6H, t, 3JHH = 7.6, (CH2)3 N+]; 3.59, [6H, t, 3JHH = 7.6, (CH2)3 N]; 4.17 (2H, s, N+CH2COOEt); 4.21 (2H, q, 3JHH = 7.2, COOCH2CH3). 13C NMR (400 MHz, D2O): 13.10, 43.97, 52.79, 61.67, 63.42, 164.70.

Iodometric titrations

Titanium (II) chloride solution (≥ 12%) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich. Hydrochloric acid (37%), sulfuric acid (1 M), sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate and potassium iodide were purchased from VWR.

Methods

Fast kinetics experiments

The chemical reactions were conducted using the stopped flow mixer Bio-Logic SFM-3000 and an ASPEN TIDAS array spectrophotometer. The SFM-3000 reactor allows the precise injection and mixing of small amounts (μl range) of reagents. The mixed solution passes into a Quartz cuvette, with 1.5 mm of light path length, where it is exposed to the light of a xenon mercury lamp. The absorbance information of the solution is collected at every fraction of a second, between the wavelength of 180 and 800 nm. The data were processed using the software Bio-Kine32 version 4.64.

The Bio-Logic SFM-3000 reactor was used to follow the stability of the catalysts and their impact on the reaction of hypochlorous acid with chlorite ions. The experiments were performed at 25 °C and pH 5 since there is evidence that in these conditions the chloroammonium cation of DABCO presents good oxidation results (Afsahi et al. 2015). The molar mixing proportions were 1:1:1 in all the cases, except for the catalyst dosage experiment. The initial concentration of the reagents in the mixed solution was approximately 5 mM, and the real concentration values of the reagents inside the cuvette were calculated using Beer’s law equation and the measured absorbance values. The error for this technique is ± 5% of the measured absorbance value. Table 1 presents the molar absorptivity values (ɛ) for \({\text{HOCl}}\), \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) which were taken from previous literature (Körtvélyesi 2004) and mostly confirmed within the current experiments. The only value that differed from the literature was the ɛ of chlorine dioxide at 235 nm. The value proposed by Körtvélysi (167 M−1 cm−1) delivered amounts of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) that did not correspond to the titration results nor the calculated \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) quantities using the measured absorbances at ɛ at 360 nm. It is probable that the literature value experienced interference at 235 nm that was not present within these measurements.

Baseline and slope corrections were applied to all the spectra obtained, and the absorbance contribution from other species was subtracted in order to obtain the concentration of the species of interest. All the experiments were done three times.

Iodometric titration

The iodometric titration was used to confirm the concentrations of \({\text{HOCl}}\), \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\), \({\text{ClO}}_{3}^{ - }\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) in the system. The method was first proposed by Wartiovaara (1982) and is based on the reduction of chlorine species by iodine ions at different pH values.

pKa measurement

A pH titration was used to identify the pKa of CEM-DABCO. An aqueous solution of CEM-DABCO (50 mM, 5 ml) with original pH 3.36 was acidified to pH 2.45 with a slow addition of 2.5 M HCl. Then, the sample was titrated with 1 M NaOH, monitoring the changes in pH.

Results and discussion

Optimal pH for the chloroammonium cation of CEM-DABCO

Chloroammonium cations are formed between \({\text{HOCl}}\) and unprotonated tertiary amines (Prütz 1998), with the protonation of the catalyst reducing its ability to form the chloroammonium cation. To determine the pKa of CEM-DABCO, its acidic solution was titrated with \({\text{NaOH}}\) (Fig. 3). The titration curve has two inflection points at pH 3.0 and 7.5, confirming the results from previous studies (Dawson 2018). The first value corresponds to the pKa of CEM-DABCO, while the second inflection was likely caused by the alkali-catalyzed hydrolysis of the methyl ester and neutralization of the formed CM-DABCO (Dawson 2018). On the other hand, \({\text{HOCl}}\) is always in equilibrium with other chlorine species (\({\text{Cl}}_{2}\) and \({\text{ClO}}^{ - }\)). This equilibrium is pH dependent, with \({\text{HOCl}}\) being the dominant chlorine species between pH 3.5–7.5. As a compromise, pH 5 was selected for the experiments. At this pH, the chloroammonium formation is fast due to the abundance of \({\text{HOCl}}\) and unprotonated CEM-DABCO. This pH is similar to the range where the chloroammonium cation of the other alkyl-substituted DABCO was seen (Afsahi et al. 2019).

Catalyst stability

In buffer pH 5

The pH 5 buffer solution, DABCO and CEM-DABCO have their maximum absorbance in the same wavelength region, from 198 to 203 nm. The spectra of the buffer were subtracted to obtain the molar absorptivity values of the catalysts. DABCO and CEM-DABCO have molar absorptivities of 478 M−1 cm−1 (at 203 nm) and 317 M−1 cm−1 (at 201 nm) respectively.

DABCO and CEM-DABCO were stable in buffer pH 5, presenting no change in the absorbance value at 201 and 203 nm during a 600-s measurement. No decrease in the absorbance at 201–203 nm nor new peaks were detected. These results are consistent with general knowledge of amines stability in aqueous environment (McMurry 1998). In aqueous solutions, amines (such as DABCO and CEM-DABCO) reach equilibrium by receiving \({\text{H}}^{ + }\) from water or the buffer. CEM-DABCO is additionally a quaternary ammonium salt, with a chloride counter ion, and thus, would dissociate in solution. The catalyst is therefore positively charged even before amine protonation. At pH 5, DABCO is similarly positively charged, but this is due to the protonation of one amine. No other changes were expected in CEM-DABCO at pH 5 since esters are stable at this pH (McMurry 1998) and catalyzed hydrolysis of CEM-DABCO is a slow process that would require a significantly longer time frame to take place.

With chlorite ions

The stability of DABCO and CEM-DABCO in \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) was analyzed by mixing equal moles of catalyst and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) at pH 5. Figure 4 presents the spectra of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) and the catalysts at 0.6, 300 and 600 s. Figure 4 a shows the spectra of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) at pH 5. As expected (Shelly 1960) at this mildly acidic pH, \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) is consumed, shown by a decrease in the absorbance at 260 nm, and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) is produced, with an increase in the absorbance at 360 nm. A similar behavior is observed in Fig. 4 b, where CEM-DABCO is additionally present in the system, suggesting that CEM-DABCO is not reacting with \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\). The spectra of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) with DABCO are presented in Fig. 4 c. At pH 5, \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) is converted into \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), which in turn reacts with DABCO. Hence, DABCO is not stable in the presence of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) at pH 5.

In hypochlorous acid

The stability of DABCO and CEM-DABCO with \({\text{HOCl}}\) was studied by mixing equal moles of \({\text{HOCl}}\) with the catalyst at pH 5. Figure 5a–c presents the spectra of \({\text{HOCl}}\) in buffer with the catalysts. \({\text{HOCl}}\) degrades slowly at pH 5 (Fig. 5a), which can be observed from the decrease in the absorbance at 235 nm in time. The addition of CEM-DABCO to \({\text{HOCl}}\) (Fig. 5b) produces the chloroammonium cation, which in this case seems to have a similar absorption and stability to \({\text{HOCl}}\) at pH 5. In contrast, DABCO reacts rapidly with \({\text{ HOCl}}\) (Fig. 5c), in the reaction described by Dennis et al. (1967), with the chloroammonium cation degrading to 1,4-dichloropiperazine and formaldehyde (Dennis et al. 1967). The very broad and intense peak of absorbance from 200 to 380 nm was also observed in similar experiments by Rosenblatt et al. (1972), who proposed that the peak is related to the chloroammonium cation and its degradation products, with a chloroammonium cation molar absorptivity value of 139 M−1 cm−1 at 357 nm.

These findings on the UV/Vis absorbance of CEM-DABCO and DABCO relate to previous studies, which have shown the poor predictability in the visibility of the chloroammonium cation. For example, the chloroquinuclidinium ion has shown a visible absorbance, while the trimethyleneammonium ion has not (Ellis and Soper 1954; Pitman et al. 1969). A possible hypothesis is that the chloroammonium itself should have a similar absorbance to the catalyst, and that the visible new peaks correspond mostly to the degradation products of the chloroammonium cations.

Catalyst stability with chlorine dioxide

The stability of DABCO and CEM-DABCO in \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) was analyzed by mixing equal moles of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) and catalysts in the buffer solution. Figure 6 presents the spectra of the mixed solutions at 0.26 s and after 600 s. It can be seen that at pH 5, \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) is unstable (Körtvélyesi 2004), degrading over time, shown by a decrease in its absorbance at 360 nm. A similar decrease in the absorbance of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) is observed in Fig. 6b, meaning that CEM-DABCO does not contribute to \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) degradation, and hence, is stable in the presence of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\). Figure 6c shows the spectra of DABCO and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\). As reported by previous studies (Dennis et al. 1967; Hull et al. 1967), \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) degrades DABCO, which is observed in the decrease in the absorbance at 360 nm. The oxidation of DABCO by ClO2 produces piperazine, formaldehyde and chlorite ions (Hull et al. 1967; Dennis et al. 1967) causing an increase in absorbance at 201 nm and at 260 nm. Figure 6d summarizes the rate of degradation of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) in time with each catalyst. Notably, there is a lower rate of degradation of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) in the presence of CEM-DABCO than in the reference system. This smaller rate suggests that the catalyst is both stable and has a positive effect on \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) stability.

Effect of tertiary amine catalyst on the reaction of hypochlorous acid with chlorite ions

As discussed, the reaction between \({\text{HOCl}}\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) is a significant reaction in chlorine dioxide industrial treatments. It produces dichlorine dioxide (\({\text{Cl}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{2}\)) as an intermediate species, and this then further reacts with other chlorine species and with water, regenerating \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), but also producing chlorate and chloride ions. Figure 7 presents the \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) generation from the reaction of \({\text{HOCl}}\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) at pH 5. The catalyzed systems with DABCO and CEM-DABCO display a faster \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) production than the non-catalyzed reaction. In less than one second (1 s), approximately 5 mM of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) are produced, while it takes more than twenty seconds (20 s) to produce the same amount in the non-catalyzed reaction. Using Fig. 7 a, it was also possible to calculate the initial speed of reaction (k) for \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) formation. The initial rate of the non-catalyzed, DABCO-catalyzed, and CEM-DABCO-catalyzed reactions were 0.4, 20 and 30 mM s−1, respectively. Hence, the \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) formation of the CEM-DABCO-catalyzed reaction of \({\text{HOCl}}\) with \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) is approximately 80 times faster than the non-catalyzed one.

\({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) production from the catalyzed and non-catalyzed reaction of HOCl with \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) at pH 5, initial concentrations of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) 0 mM, HOCl 5 mM, \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) 5 mM and catalysts 0.5 mM. a \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) amounts calculated from the absorbance at 359 nm, b \({\text{HOCl}}\) concentration, measured absorbance at 234 nm, c \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) concentration, measured absorbance at 260 nm

The main difference between the two catalyzed systems is the stability of their catalysts. CEM-DABCO is stable, and hence, it can be assumed that the increase in the speed of chlorine dioxide formation is completely due to the catalyst. In contrast, DABCO is unstable in the presence of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), forming formaldehyde as a degradation product, which has been reported to react with \({\text{ HClO}}_{2}\), regenerating \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) (Ventorim et al. 2005; Jiang et al. 2007). Therefore, the catalytic effect in the DABCO system should be considered as the overall impact of both DABCO and formaldehyde.

The change in the reagent concentrations is presented in Fig. 7b and c, where the \({\text{HOCl}}\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) are consumed rapidly in the catalyzed reactions. In less than 1 s, the \({\text{ HOCl}}\) concentration drops from 5 to 2 mM in the CEM-DABCO-catalyzed reaction, while it takes approximately 15 s to reach the same concentration of \({\text{HOCl}}\) in the non-catalyzed reaction. The 5 mM of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) was fully consumed in less than 1 s when CEM-DABCO was used, whereas it took more than 20 s to consume the same amount of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) in the non-catalyzed reaction. The apparent lower consumption of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) (2.5 mM) and \({\text{HOCl}}\) (0.5 mM) in the DABCO-catalyzed reaction should be interpreted as degradation products from the chloroammonium cation of DABCO which are formed in this range of wavelengths. These results support that the tertiary amines increase the speed of reaction of chlorine dioxide regeneration and suggest that the stoichiometry of the system remains unchanged.

An iodometric titration was used to confirm the hypothesis that the catalyst does not change the stoichiometry of the reaction of \({\text{HOCl}}\) with \({\text{ ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\). This technique was used to overcome the spectrometry restrictions on identifying chlorate (\({\text{ClO}}_{3}^{ - }\)), and the uncertainty of concentrations in a mix of chlorinated species in the absorbance at 235 and 260 nm. Table 2 presents the final amounts of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), \({\text{HOCl}}\), and \({\text{ClO}}_{3}^{ - }\) (at 15 and 60 s) in the reaction system of \({\text{HOCl}}\), \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) and catalyst. In general, it can be observed that similar amounts of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), \({\text{HOCl}}\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{3}^{ - }\) are produced with or without either catalyst. These results support the hypothesis that the equilibria of the reaction are not changed by addition of catalyst.

Based on these titration results and previous knowledge of the stoichiometry and reaction rates of the reaction of \({\text{HOCl}}\) with \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\), as shown in Fig. 1 (Tarvo et al. 2009; Jia et al. 2000), a rudimentary overall balance of Cl is estimated. The initial concentration of \({\text{Cl}}\) atoms in the mixture was 14.3 ± 1.0 mM (6 mM \({\text{HOCl}}\), 5.2 mM \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) and 3.1 mM \({\text{ClO}}_{3}^{ - }\)), and after 15 s there remains only an average of 10.9 mM of \({\text{Cl}}\) atoms (4.7 mM \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), 2.4 mM \({\text{HOCl}}\) and 3.8 mM \({\text{ClO}}_{3}^{ - }\)). Henceforth, it is evident that approximately 3.4 mM \({\text{Cl}}\) atoms are missing.

Analyzing Fig. 1, the reagents (\({\text{HOCl }}\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - } )\) react in the rate determining step forming the intermediate \({\text{Cl}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{2}\), and afterward, there are four possible routes for it to react (Reactions 2, 3, 4 and 5). In this stoichiometry determining part of the reaction, Reaction 4 is known to be predominant over Reaction 3 in the production of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) (Tarvo et al. 2009; Jia et al. 2000; Fabian and Gordon 1992). Combining Reactions 1 and 4 (Eq. 1), and knowing that the average initial amounts of \({\text{HClO}}_{2}\) and \({\text{HOCl}}\) in the system was 5 mM, it can be supported that approximately 4.7 mM of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) and 2.35 mM of \({\text{Cl}}^{ - }\) are produced when the equilibrium is reached, at approximately 15 s. A similar assumption can be made for the production of \({\text{ClO}}_{3}^{ - }\), which can be produced either via Reactions 2 and 5, with Reaction 2 being faster than Reaction 5 (Jia et al. 2000; Fabian and Gordon 1992). Therefore, combining Reactions 1 and 2 (Eq. 2), and knowing that 0.7 mMol of \({\text{ClO}}_{3}^{ - }\) was produced, it can be assumed that a similar amount of \({\text{Cl}}^{ - }\) was generated via Reaction 2. In summary, at least 3.2 mMol of \({\text{Cl}}^{ - }\) is produced in the system after 15 s. A different situation results after 60 s, where chlorine dioxide is degraded due to the pH and an even more complex reaction system is taking place and as such will not be discussed in this article.

Impact of catalyst dosage

As shown, due to its high stability and activity in the reaction system, CEM-DABCO has a high potential as a catalyst, and hence, it is interesting to analyze the effect of its chloroammonium cation in the production of chlorine dioxide. Figure 8 presents the impact of catalyst dosage on the production of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\). It can be seen that while higher amounts of catalyst result in higher k values, they eventually lead to similar chlorine dioxide amounts (5.2 mM \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\)), displaying that the stoichiometry of the reaction is not changed by the catalyst, taking into consideration that this technique has an error of ± 5%.

The initial rate of reaction of the non-catalyzed \({\text{ClO}}_{2} { }\) regeneration is doubled with 0.005 mM of CEM-DABCO and increases with the catalyst amount up to 27.2 mM/s (with 0.5 mM of catalyst), which corresponds to an increase of 45 times the original speed of reaction. The small differences among the k values presented in the current and previous sections are believed to originate from the small differences in the amounts of initial reagents (\({\text{HOCl}}\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\)) as well as some impurities present in them, especially \({\text{NaClO}}_{3}\) or \({\text{NaCl }}\)(Tarvo 2010).

Table 3 presents the results of the titration that confirm the hypothesis that the stoichiometry of the reaction is not modified by higher amounts of catalyst. At 15 s, the amounts of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\) are similar, but after 60 s, the titration reveals a slightly higher amount of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) for the catalyzed reactions, suggesting that the catalyst has a positive impact on the stability of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\).

Conclusion

CEM-DABCO catalyzes successfully the reaction of \({\text{HOCl}}\) with \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\). When this tertiary amine catalyst is present in the reaction system, the rate of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) production is increased, and the \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) is of a higher stability. The catalyst dosage has a significant impact on the initial rate of formation of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), but even small dosages (such as 0.001 times the amounts of reagents) can still double the initial speed of reaction. Higher catalyst amounts lead to faster production of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), up to 8, 40 or even more than 90 times faster, than the non-catalyzed reaction. The positive effect of the catalyst on \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) amounts can be explained by its high stability with \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\) and \({\text{ClO}}_{2}^{ - }\), unlike its base structure DABCO, which degrades rapidly in their presence.

This study constitutes an advance in the knowledge of chlorine chemistry and presents potential applications in the production of \({\text{ClO}}_{2}\), or within applications where it is consumed via the oxidation of organic substrates.

References

Afsahi G, Chenna NK, Vuorinen T (2015) Intensified and short catalytic bleaching of eucalyptus kraft pulp. Ind Eng Chem Res 54:8417–8421. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.5b01725

Afsahi G, Bertinetto C, Hummel M et al (2019) Catalytic efficiency and stability of tertiary amines in oxidation of methyl 4-deoxy-Β-L-threo-hex-4-enopyranosiduronic acid by hypochlorous acid. Mol Catal 474:110413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcat.2019.110413

Ammer J, Baidya M, Kobayashi S, Mayr H (2010) Nucleophilic reactivities of tertiary alkylamines. J Phys Org Chem 23:1029–1035. https://doi.org/10.1002/poc.1707

Basavaiah D, Reddy BS, Badsara SS (2010) Recent contributions from the Baylis–Hillman reaction to organic chemistry. Chem Rev 110:5447–5674. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr900291g

Benisti A (2018) Disintectant for drinkable water, food contact, industry, spas, swimming pools and air sterilization. U.S. Patent application 15/747. 394

Brennesein P, Grob CA, Jackson R, Ohta M (1965) Die Synchrone Fragmentierung von γ-Amino-cycloalkylhalogeniden. 2. Teil. Solvolysen von 4-Bromchinuclidin. Fragmentierungs-Reaktionen, (The synchronized fragmentation of γ-amino-cycloalkyl halides. Part 2. Solvolysis of 4-bromoquinuclidine. Fragmentation reactions), 12. Mitteilung. Helv Chim Acta 48:146

Dawson OJG (2018) The activity and stability of tertiary catalysts in the presence of hypochlorous acid. Master thesis, Aalto University

Dennis WH, Hull LA, Rosenblatt DH (1967) Oxidations of amines. IV. Oxidative fragmentation. J Org Chem 23:3783–3787. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo01287a012

Dodd MC, Shah AD, von Gunten U, Huang CH (2005) Interactions of fluoroquinolone antibacterial agents with aqueous chlorine: reaction kinetics, mechanisms, and transformation pathways. Environ Sci Technol 39:7065–7076. https://doi.org/10.1021/es050054e

Ellis AJ, Soper FG (1954) Studies of N-halogeno-compunds. Part VI. The kinetics of chlorination of tertiary amines. J Chem Soc. https://doi.org/10.1039/JR9540001750

Engel R, Rizzo JLI, Rivera C et al (2009) Polycations. 18. The synthesis of polycationic lipid materials based on the diamine 1, 4-diazabicyclo [2.2. 2] octane. Chem Phys Lipid 158:61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2008.12.003

Fabian I, Gordon G (1992) Iron (III)-catalyzed decomposition of the chlorite ion: an inorganic application of the quenched stopped-flow method. Inorg Chem 31:2144–2150. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic00037a030

Gallard H, von Gunten U (2002) Chlorination of natural organic matter: kinetics of chlorination and of THM formation. Water Res 36:65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0043-1354(01)00187-7

Gombas D, Luo Y, Brennan J et al (2017) Guidelines to validate control of cross-contamination during washing of fresh-cut leafy vegetables. J Food Prot 80:312–330. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-258

Gordon G, Rosenblatt AA (2005) Chlorine dioxide: the current state of the art. Ozone Sci Eng 27:203–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/01919510590945741

Hardee KL, Gordon AZ, Pyle CB, Sen RK (1983) Method and catalyst for making chlorine dioxide. U.S. Patent 4,381,290

Huang K, Shah AD (2018) Role of tertiary amines in enhancing trihalomethane and haloacetic acid formation during chlorination of aromatic compounds and a natural organic matter extract. Environ Sci Water Res Technol 4:663–679. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ew00439g

Hull LA, Davis GT, Rosenblatt DH, Williams HKR, Weglein RC (1967) Oxidations of amines. III. Duality of mechanism in the reaction of amines with chlorine dioxide. J Am Chem Soc 89:1163–1170. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00981a023

Jia Z, Margerum DW, Francisco JS (2000) General-acid-catalyzed reactions of hypochlorous acid and acetyl hypochlorite with chlorite ion. Inorg Chem 39:2614–2620. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic991486r

Jiang ZH, Van Lerop B, Berry R (2007) Improving chlorine dioxide bleaching with aldehydes. J Pulp Pap Sci 33:89–94

Kolar JJ, Lindgren BO, Pettersson B (1983) Chemical reactions in chlorine dioxide stages of pulp bleaching. Wood Sci Technol 17:117–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00369129

Körtvélyesi Z (2004) Analytical methods for the measurement of chlorine dioxide and related oxychlorine species in aquous solution. Doctoral dissertation, Miami University

Lehtimaa T, Tarvo V, Kuitunen S, Jääskeläinen A-S, Vuorinen T (2010) The effect of process variables in chlorine dioxide prebleaching of birch kraft pulp. Part 2. AOX and OX formation. J Wood Chem Technol 30:19–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02773810903276684

Masschelein W (1967) Preparation of pure chlorine dioxide. Reactions of chlorine or sodium hypochlorite with sodium chlorite in the presence of acetic anhydride. Ind Eng Chem Prod Res Dev 6:137–142. https://doi.org/10.1021/i360022a013

McMurry J (1998) Amines. In: Fundamentals of organic chemistry, 4th edn. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company, Pacific Grove, pp 329–336, 380–401

Pitman IH, Dawn HS, Higuchi T, Hussain A (1969) Prediction of chlorine potentials of N-chlorinated organic molecules. J Chem Soc B Phys Org 626:1230–1232. https://doi.org/10.1039/J29690001230

Prütz WA (1998) Reactions of hypochlorous acid with biological substrates are activated catalytically by tertiary amines. Arch Biochem Biophys 357:265–273. https://doi.org/10.1006/abbi.1998.0822

Prütz WA, Kissner R, Koppenol WH (2001) Oxidation of nadh by chloramines and chloramides and its activation by iodide and by tertiary amines. Arch Biochem Biophys 393:297–307. https://doi.org/10.1006/abbi.2001.2503

Ringo JP (1991) Catalyst enhanced generation of chlorine dioxide. U.S. Patent 5,008,096

Rosenblatt DH, Demek MM, Davis GT (1972) Oxidations of amines. XI. Kinetics of fragmentation of triethylenediamine chlorammonium cation in aqueous solution. J Org Chem 37:4148–4151. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo00798a040

Sardon H, Pascual A, Mecerreyes D, Taton D, Cramail H, Hedrick JL (2015) Synthesis of polyurethanes using organocatalysis: a perspective. Macromolecules 48:3153–3165. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00384

Shah AD, Kim JH, Huang CH (2011) Tertiary amines enhance reactions of organic contaminants with aqueous chlorine. Water Res 45:6087–6096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2011.09.010

Shelly JK (1960) The theory and practice of sodium chlorite bleaching. J Soc Dye Colour 76:469–479

Sixta H, Süss H-U, Schwanninger M, Krotscheck AW (2006) 7.4 chlorine dioxide bleaching. Sixta H(ed) Handbook of pulp. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co., KGaA, Weinheim, Germany, pp 734–771

Svenson DR, Jameel H, Chang HM, Kadla JF (2006) Inorganic reactions in chlorine dioxide bleaching of softwood kraft pulp. J Wood Chem Technol 26:201–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/02773810601023255

Tarvo V (2010) Modeling chlorine dioxide bleaching of chemical pulp. Doctoral dissertation, Aalto University School of Science and Technology

Tarvo V, Lehtimaa T, Kuitunen S, Alopaeus V, Vuorinen T, Aittamaa J (2009) The kinetics and stoichiometry of the reaction between hypochlorous acid and chlorous acid in mildly acidic solutions. Ind Eng Chem Res 48:6280–6286. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie801798m

Ventorim G, Colodette JL, Eiras KMM (2005) The fate of chlorine species during high temperature chlorine dioxide bleaching. Nord Pulp Pap Res J 20:7–11. https://doi.org/10.3183/npprj-2005-20-01-p007-011

Wartiovaara I (1982) The influence of pH on the D1 stage of a D/CED1 bleaching sequence. Pap Puu 64:534–545

Ye B, Cang Y, Li J, Zhang X (2019) Advantages of a ClO2 /NaClO combination process for controlling the disinfection by-products (DBPs) for high algae-laden water. Environ Geochem Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-018-0231-8

Acknowledgements

This work was cofunded by Andritz, Kemira, Metsä Fibre, Stora Enso, UPM, Suzano Pulp and Paper and Aalto University.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Aalto University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Isaza Ferro, E., Perrin, J., Dawson, O.G.J. et al. Tertiary amine-catalyzed generation of chlorine dioxide from hypochlorous acid and chlorite ions. Wood Sci Technol 55, 67–81 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-020-01247-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-020-01247-5