Abstract

People with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) frequently show the symptoms of oversensitivity to sound (hyperacusis). Although the previous studies have investigated methods for quantifying hyperacusis in ASD, appropriate physiological signs for quantifying hyperacusis in ASD remain poorly understood. Here, we investigated the relationship of loudness tolerance with the threshold of the stapedial reflex and with contralateral suppression of the distortion product otoacoustic emissions, which has been suggested to be related to hyperacusis in people without ASD. We tested an ASD group and a neurotypical group. The results revealed that only the stapedial reflex threshold was significantly correlated with loudness tolerance in both groups. In addition to reduced loudness tolerance, people with lower stapedial reflex thresholds also exhibited higher scores on the Social Responsiveness Scale-2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hyperacusis is a disorder characterized by excessive responses to auditory stimulation. The stapedial reflex (SR) has been extensively studied as a means of quantifying the degree of hyperacusis (Olsen 1999). Although the threshold of this reflex has been reported to be lower in people with a relatively weak tolerance for loud noise (McCandless and Miller 1972; Greenberg and Mcloed 1979; Olsen 1999; Al-Azazi and Othman 2000), several previous studies have not supported this relationship (Denenberg and Altshuler 1976; Holmes and Woodford 1977; Ritter et al. 1979). This discrepancy can be explained by inconsistent factors in experimental design, such as the stimuli used or the hearing function of the participants (Al-Azazi and Othman 2000). More recently, Knudson et al. (2014) observed that contralateral suppression of distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE) is increased in patients with hyperacusis. While the mechanisms underlying this excessive DPOAE suppression are unknown, these results suggest that inner ear function can predict hyperacusis.

A number of studies have reported abnormal responses to auditory stimuli among people with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). Although ASD patients commonly exhibit both hypersensitivity to auditory stimuli and cases of hypoactivity, it is primarily hypersensitivity that it is considered a problem in daily life (Elwin et al. 2012; Robertson and Simmons 2015). More than half a century ago, Kanner noted that people with autism showed excessive reactions to specific sounds (Kanner 1943). More recently, Khalfa et al. (2004) reported that, compared with typically developing (TD) participants, people with ASD exhibited stronger discomfort in response to auditory stimulation. However, it remains unclear whether SR threshold or DPOAE can be used as markers for the degree of auditory sensitivity in people with ASD.

Although several studies have reported that SR threshold in children with ASD does not differ significantly from that in TD children (Gomes et al. 2004; Gravel et al. 2006; Tharpe et al. 2006), a more recent study found significant differences in the low-frequency band (Lukose et al. 2013). In addition, the reported differences in DPOAE suppression between ASD and TD are also controversial, because they are not always observed, even under similar experimental conditions (Danesh and Kaf 2012; Kaf and Danesh 2013). Furthermore, the relationship between hyperacusis in ASD and inner ear function remains poorly understood.

Tolerance levels for pure-tone sound have frequently been used to evaluate hyperacusis. However, in the current study, we used speech sounds as stimuli, because sensitivity for speech sound is higher than that for pure tones (Smith and Bennetto 2007). Furthermore, we used a visual analog scale to evaluate hyperacusis using a finer scale, rather than a binary measure.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has examined the relationship between loudness tolerance and either SR threshold or DPOAE suppression in ASD. In the current study, we examined these relationships to establish a new marker for hyperacusis in ASD.

Methods

Participants

21 healthy adults (TD group) and 14 people with ASD (ASD group) participated in the current study. Members of the TD group were recruited by a temporary employment agency. Members of the ASD group were recruited online and had ASD or another relevant disorder [pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), attention deficit (AD), high functioning autism (HFA), Asperger’s syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorders—not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)]. The two groups were matched for age and sex (Table 1). There were no eligibility criteria. Subjects have self-reported on the diagnosis of ASD or other relevant disorders, and one of the authors confirmed the medical certificate.

To assess autistic traits, each participant completed the Social Responsiveness Scale-2 (SRS-2) (Constantino and Gruber 2012). A significant group difference in SRS-2 score was found using Welch’s t test (t(19) = 8.26, p < 0.001).

Apparatus

All experimental procedures were conducted in a soundproof room (YAMAHA, Shizuoka, Japan). The amount of noise attenuation in the soundproof room was 15 dB, as measured by an NL-27K-1822 noise meter (Rion, Tokyo, Japan).

SR threshold and DPOAE were measured using a tympanometer (Titan, DiaTec Company, Kawasaki Saiwai-ku, Kanagawa, Japan). Before the experiment, we selected an earpiece (Titan, Diatec) for each participant to prevent air leaks. Aside from the stimuli used to induce the SR and DPOAE, all other auditory stimuli were delivered via an audio interface (DUO-CAPTURE-EX, Roland Corporation, Hamamatsu Kita-ku, Shizuoka, Japan) using ear phones (ATH-CKS55XBK, Audio-Technica Corporation, Machida, Tokyo, Japan). We controlled the Titan devices using software (Otoaccess, Diatec) run on a Windows 8 platform. We administered the auditory stimuli using custom software developed in Scilab v5.5.2 (ESI company, Avenue de Suffren, Paris, France) for Windows 8.

Experimental procedure

We measured the SR threshold and DPOAE for all participants and obtained subjective loudness evaluations. All measurements were performed in the left ear first and then in the right ear. Each left and right ear measurement was first made, while no sound was applied to the contralateral ear. Afterward, both measurements were repeated with broad band noise ranging from 0.4 to 5 kHz applied to contralateral ear. For the SR threshold, we used the average of the data measured under both conditions, with and without contralateral noise.

To keep the duration of the experiment within 1 h, we did not repeat measurements even if the results were not reliable. To compensate for this, we excluded any unreliable data from the analysis. Regarding SR, the waveforms obtained from the measurement were regarded as unreliable if they were noisy or non-smooth (Fig. 1). For DPOAE, we used data when the reliability values calculated by Titan software were higher than 98%.

Stapedial reflex threshold

SRs were induced by 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 kHz pure tones. The inducing stimulus was first presented at a gain of 65 dB, which was incremented in steps of 3 dB until the SR was detected or until the stimulus reached the maximum level that could be induced by the apparatus.

We removed unreliable SR waveforms when the time-series of acoustic impedance was either noisy or non-smooth (Fig. 1). Furthermore, if SR thresholds could not be detected using a stimulus at the maximum dB level, we set the SR threshold to be the maximum level. The proportion of missing values of SR threshold was 22.0% of the total number of measurements.

DPOAE

We recorded the power level (DPLV), signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and noise level of the DPOAE. The sound pressure levels (SPL) for the primary and secondary tones (L1 and L2) were fixed, so that L2 = L1–10 dB. The frequencies of the two tones (f1 and f2) were fixed, so that f2/f1 = 1.22 Hz. Measurement conditions are summarized in Table 2. The proportion of missing values of DPOAE was 37.19% of the total number of measurements.

Subjective loudness evaluation

Participants heard several speech stimuli and were asked to evaluate the loudness using a visual analog scale from 0 (silent) to 10 (unbearably loud). We used four voices from the Online gaming voice chat corpus with emotional label (OGVC) provided by the Speech Resources Consortium at the National Institute of Informatics (NII-SRC, Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan). Based on a previous report that speech stimuli elicit a lower response sound pressure than pure-tone stimuli in children with autism (Smith and Bennetto 2007), we predicted that speech stimuli would be better suited for examining auditory hypersensitivity. Since all participants in this experiment were Japanese, we used a Japanese speech corpus. OGVC was selected, because it does not include dialects, and included variations such as emotion representation.

We selected two surprise voices, one angry voice, and one fearful voice, which were spoken by actors, from the OGVC. We prepared the stimuli for each voice at five decibel levels (0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 dB).

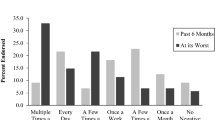

Each participant completed four sessions. Each session included five randomly chosen stimuli that were presented from low to high volume. If participants could not stand the loud sounds, they were able to decrease the number of stimuli per session. As a result, two participants from the ASD group skipped stimuli ≥ 15 dB and 17 participants from both groups skipped stimuli ≥ 20 dB. Therefore, missing data constituted 6.36% of the total number of measurements.

Data analysis

DPOAE suppression

We analyzed DPLV when the Titan tympanometer indicated that reliability was greater than 98%. The change in DPLV elicited by contralateral noise was quantified as a magnitude ratio (no noise/noise) and expressed in decibels. The mean change for each condition was calculated for each ear. We analyzed the magnitude change for each condition when a significant suppression (or facilitation) of DPLV was identified. Mean magnitude changes were considered significant when their 95% confidence intervals excluded zero (Knudson et al. 2014).

Normalized mean

Because of missing values, the amount of usable data was not always the same across conditions. To compensate for this and to allow us to explain overall trends among the participants, we calculated the normalized mean for each parameter (SR thresholds, DPOAE suppression, and loudness-evaluation scores). First, we normalized all the data, so that the mean was 0 and the standard deviation was 1 for each measurement condition. We then averaged all data from each ear of each participant. The value resulting from this procedure was defined as the normalized mean.

Hyperacusis index

We defined the hyperacusis index for each participant as the normalized mean of the subjective loudness-evaluation score from the subjective loudness-evaluation task.

Statistical analysis

For each variable, we conducted a two-factor mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Group (TD vs. ASD) and Ear (left vs. right) as the factors. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using the Bonferroni method. Correlations were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

SR threshold can be an indicator of hyperacusis regardless of group

For both groups, we examined whether the SR threshold or DPOAE suppression was correlated with the hyperacusis index. We removed unreliable SR thresholds from the analysis (see “Methods”). The number of samples and the correlation results for the SR threshold are summarized in Table 3. Correlation coefficients in all the conditions were negative, but statistical significance was limited to: 1 kHz in the ASD group (both ears), 1 kHz in the TD group (left ear), 2 kHz in both groups (right ear), and 3 kHz in the TD group (left ear). For both groups, the normalized mean-SR thresholds were significantly correlated with the hyperacusis index (ASD group: ρ = − 0.673, p = 0.0281; TD group: ρ = − 0.555. p = 0.0102. Fig. 2), indicating that, while SR threshold under specific conditions is not a good indicator of hyperacusis, the normalized mean threshold across multiple conditions was a predictive index for hyperacusis. In addition, we observed a significant negative correlation between SRS-2 scores and the normalized mean-SR threshold across conditions (ρ = − 0.369, p = 0.0376, Fig. 3). We also observed an almost significant correlation between SRS-2 scores and the normalized mean-SR threshold in the ASD group (ρ = − 0.609, p = 0.052), but not in the TD group (ρ = 0.0630, p = 0.786).

For DPOAE suppression, the conditions resulting in a significant suppression (or facilitation) were limited (Table 4). Analysis of these conditions indicated that DPOAE suppression did not correlate significantly with the hyperacusis index (Table 5). Furthermore, similar results were obtained for the normalized mean-DPOAE suppression across conditions (ASD group: ρ = 0.112, p = 0.733; TD group: ρ = − 0.181, p = 0.458), indicating that the normalized mean-DPOAE suppression was not a good predictor of hyperacusis.

Both hyperacusis and lower SR threshold are exhibited by the ASD group

The two-factor ANOVA revealed a main effect of group on the hyperacusis index (ASD: mean = 0.426; TD: mean = − 0.21; F(1,33) = 5.50, p = 0.0251; Fig. 4), indicating that hyperacusis was significantly greater in the ASD group. We did not find a main effect of Ear (F(1,33) = 0.0049, p = 0.945) or any interaction (Group × Ear: F(1,33) = 0.231, p = 0.634). These results indicate that the ASD group had less tolerance for loud noises than the TD group.

Consistent with these results, we also found a main effect of group on the normalized mean-SR threshold across conditions (ASD: mean = − 0.654; TD: mean = 0.327; F(1,16) = 7.68, p = 0.0136; Fig. 5), indicating that SR threshold was significantly lower in the ASD group. Analysis revealed no main effect of ear (F(1,16) = 0.0478, p = 0.8298) and no significant interaction (F(1,16) = 0.430, p = 0.5214). Furthermore, SR threshold was significantly lower in the ASD group in the 1–3 kHz range (1 kHz: ASD = 81.0, TD = 88.3, F(1,16) = 6.38, p = 0.0225; 2 kHz: ASD mean = 83.0, TD mean = 92.1, F(1,16) = 10.9, p = 0.0045; 3 kHz: ASD mean = 83.3, TD mean = 91.3, F(1,16) = 10.7, p = 0.0048, Fig. 6).

These results suggest that hyperacusis was a more prominent feature in ASD than in TD individuals, and that SR threshold was an appropriate index for examining hyperacusis in ASD.

Discussion

In the current study, we examined whether inner ear function could explain hyperacusis in ASD. First, we determined how well the hyperacusis index correlated with the SR threshold and with DPOAE suppression, in both the ASD and TD groups. We used this method, because hearing ability affects the relationship between the hyperacusis index and these measurements. We found that only SR threshold was correlated with the hyperacusis index in both groups. In addition, we found that the SR threshold for the ASD groups was lower than that for the TD group. Finally, we found that the SR threshold was correlated with sociality index scores. Taken together, these results suggest that hyperacusis in ASD can be explained by a highly sensitive inner ear.

We examined the SR threshold in adults, and observed that it was lower in people with ASD compared with TD individuals. In a previous study, children with ASD were also reported to have lower SR thresholds (Lukose et al. 2013). However, some previous studies reported no significant difference in SR threshold between children with and without ASD (Tharpe et al. 2006; Gravel et al. 2006). Differences in the age range of the included subjects may have caused the inconsistent results between the previous studies. In addition, several previous studies suggested that SR thresholds are affected by aging (Silman 1979; Gelfand and Piper 1981; Silverman et al. 1983) and early development (Mazlan et al. 2007). The results of the present study indicate that a low SR threshold can provide an indicator for hyperacusis among young adults. However, it is necessary to conduct experiments with the other age groups to confirm the generalizability of the SR threshold as an index of hyperacusis.

In contrast, the current results did not confirm a relationship between the hyperacusis index and DPOAE contralateral suppression in either group. These findings are inconsistent with the results of Knudson et al. (2014), but can be explained by differences in pathology and measurement conditions. DPOAE contralateral suppression occurs most prominently at the peak point of the DPOAE fine structure (Reuter and Hammershed 2006), suggesting that the relationship between suppression and frequency involves negligible inter-individual differences. Thus, because of such variability, DPOAE contralateral suppression may not provide a suitable method for evaluating hyperacusis. However, to detect the peak of the DPOAE fine structure, a frequency resolution of 10–20 Hz is required (Sun 2008). Therefore, it is possible that DPOAE contralateral suppression could not be evaluated properly using our measurement method.

The SR is affected not only by the function of the inner ear but also by the brainstem auditory circuit (e.g., the cochlear nuclei and the superior olivary complex) (Lukose et al. 2013, 2015; Kulesza and Mangunay 2008; Kulesza Jr et al. 2011), suggesting that people with ASD may exhibit abnormalities in the brainstem (Klin 1993; Hashimoto et al. 1995). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the cortical projections involve the SR threshold, because auditory activity can be modulated by the auditory cortex (Khalfa et al. 2001).

The current study involved several potential limitations that should be considered. First, we tested a relatively small sample size. Because ASD is a heterogeneous neurological disorder, the generalizability of the current results should be confirmed in a larger ASD population. However, we observed a negative correlation between hyperacusis and SR threshold in both the TD group and the ASD group, indicating that this relationship is not sensitive to the heterogeneity in ASD. Second, we did not counterbalance the left and right ears in the current experiments, because laterality was not our focus. Thus, in the current study, we were unable to observe any laterality, and further examination is required to elucidate this issue. Third, as mentioned above, we cannot rule out the possibility that our DPOAE measurement was not sufficient for evaluating hyperacusis, because DPOAE contralateral suppression must be measured at the peak point of DPOAE fine structure. To achieve this, DPOAE must be measured repeatedly with a high-frequency resolution. Thus, we propose that the SR threshold provides a more practical way to evaluate hyperacusis than the DPOAE.

Finally, the current results confirmed that people with ASD have a reduced tolerance for loudness compared with TD individuals, and that the SR threshold was significantly correlated with sociality scores. Because the SR threshold can be easily measured even in small children, it could provide a suitable marker for detecting ASD at the early stages. To verify this possibility, SR threshold measurements should be performed in children with ASD.

References

Al-Azazi MF, Othman BM (2000) Acoustic reflex threshold and loudness discomfort. Saudi Med J 21(3):251–256

Constantino JN, Gruber CP (2012) Social responsiveness scale (SRS). Western Psychological Services, Torrance

Danesh AA, Kaf WA (2012) DPOAEs and contralateral acoustic stimulation and their link to sound hypersensitivity in children with autism. Int J Audiol 51(4):345–352. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2011.626202

Denenberg LJ, Altshuler MW (1976) The clinical relationship between acoustic reflexes and loudness perception. J Am Audiol Soc 2(3):79–82

Elwin M, Ek L, Schröder A, Kjellin L (2012) Autobiographical accounts of sensing in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 26(5):420–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2011.10.003

Gelfand SA, Piper N (1981) Acoustic reflex thresholds in young and elderly subjects with normal hearing. J Acoust Soc Am 69(1):295–297. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.385352

Gomes E, Rotta NT, Pedroso FS, Sleifer P, Danesi MC (2004) Auditory hypersensitivity in children and teenagers with autistic spectrum disorder. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 62(3B):797–801. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0004-282X2004000500011

Gravel JS, Dunn M, Lee WW, Ellis MA (2006) Peripheral audition of children on the autistic spectrum. Ear Hear 27(3):299–312. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aud.0000215979.65645.22

Greenberg HJ, McLeod HL (1979) Relationship between loudness discomfort level and acoustic reflex threshold for normal and sensorineural hearing-impaired individuals. J Speech Hear Res 22(4):873–883

Hashimoto T, Tayama M, Murakawa K, Yoshimoto T, Miyazaki M, Harada M, Kuroda Y (1995) Development of the brainstem and cerebellum in autistic patients. J Autism Dev Disord 25(1):1–18

Holmes DW, Woodford CM (1977) Acoustic reflex threshold and loudness discomfort level: relationships in children with profound hearing losses. J Am Audiol Soc 2(6):193–196

Kaf WA, Danesh AA (2013) Distortion-product otoacoustic emissions and contralateral suppression findings in children with Asperger’s Syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 77(6):947–954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.03.014

Kanner L (1943) Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child 2(3):217–250

Khalfa S, Bougeard R, Morand N, Veuillet E, Isnard J, Guenot M, Ryvlin P, Fischer C, Collet L (2001) Evidence of peripheral auditory activity modulation by the auditory cortex in humans. Neuroscience 104(2):347–358

Khalfa S, Bruneau N, Rogé B, Georgieff N, Veuillet E, Adrien JL, Barthélémy C, Collet L (2004) Increased perception of loudness in autism. Hear Res 198(1–2):87–92

Klin A (1993) Auditory brainstem responses in autism: brainstem dysfunction or peripheral hearing loss? J Autism Dev Disord 23(1):15–35

Knudson IM, Shera CA, Melcher JR (2014) Increased contralateral suppression of otoacoustic emissions indicates a hyperresponsive medial olivocochlear system in humans with tinnitus and hyperacusis. J Neurophysiol 112(12):3197–3208. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00576.2014

Kulesza RJ Jr, Lukose R, Stevens LV (2011) Malformation of the human superior olive in autistic spectrum disorders. Brain Res 1367:360–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.015

Kulesza RJ, Mangunay K (2008) Morphological features of the medial superior olive in autism. Brain Res 1200:132–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.009

Lukose R, Brown K, Barber CM, Kulesza RJ (2013) Quantification of the stapedial reflex reveals delayed responses in autism. Autism Res 6(5):344–353. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1297

Lukose R, Beebe K, Kulesza RJ Jr (2015) Organization of the human superior olivary complex in 15q duplication syndromes and autism spectrum disorders. Neuroscience 286:216–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.033

Mazlan R, Kei J, Hickson L, Stapleton C, Grant S, Lim S, Gavranich J (2007) High frequency immittance findings: newborn versus six-week-old infants. Int J Audiol 46(11):711–717

McCandless GA, Miller DL (1972) Loudness discomfort and hearing aids. Hear Aid J 25:7–32

Olsen SO (1999) The relationship between the uncomfortable loudness level and the acoustic reflex threshold for pure tones in normally-hearing and impaired listeners—a meta-analysis. Audiology 38(2):61–68

Reuter K, Hammershøi D (2006) Distortion product otoacoustic emission fine structure analysis of 50 normal-hearing humans. J Acoust Soc Am 120(1):270–279

Ritter R, Johnson RM, Northern JL (1979) The controversial relationship between loudness discomfort levels and acoustic reflex thresholds. J Am Audiol Soc 4(4):123–131

Robertson AE, Simmons DR (2015) The sensory experiences of adults with autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative analysis. Perception 44(5):569–586. https://doi.org/10.1068/p7833

Silman S (1979) The effects of aging on the stapedius reflex thresholds. J Acoust Soc Am 66(3):735–738. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.383675

Silverman CA, Silman S, Miller MH (1983) The acoustic reflex threshold in aging ears. J Acoust Soc Am 73(1):248–255. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.388856

Smith EG, Bennetto L (2007) Audiovisual speech integration and lipreading in autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 48(8):813–821. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01766.x

Sun XM (2008) Distortion product otoacoustic emission fine structure is responsible for variability of distortion product otoacoustic emission contralateral suppression. J Acoust Soc Am 123(6):4310–4320. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2912434

Tharpe AM, Bess FH, Sladen DP, Schissel H, Couch S, Schery T (2006) Auditory characteristics of children with autism. Ear Hear 27(4):430–441. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aud.0000224981.60575.d8

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in this study. The work reported in this paper was supported by a MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Constructive Developmental Science” 24119002 and 24119004. We thank Benjamin Knight, MSc., from Edanz Group (http://www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Constructive Developmental Science” 24119002 and 24119004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YO conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination of the study and performed the measurement and the statistical analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript; II performed the measurement and the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript; SK conceived the study, and participated in its design and coordination. YK participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The present study was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles, which was approved by the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology at The University of Tokyo. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of The University of Tokyo.

Informed consent

We obtained written informed consent from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohmura, Y., Ichikawa, I., Kumagaya, S. et al. Stapedial reflex threshold predicts individual loudness tolerance for people with autistic spectrum disorders. Exp Brain Res 237, 91–100 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-018-5400-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-018-5400-6