Abstract

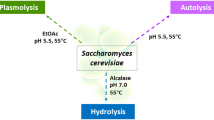

The proteinogenic composition of yeast extract products varies from experience for manufacturing reasons, though also due to the yeast starting product. Therefore, this study is the first to focus solely on the influence of three industrially applicable cell disruption methods (cell mill, ultrasonic sonotrode and autolysis) on the amino acid and protein composition of a yeast extract. A consistent spent yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae TUM 68) produced in a standardized industrial pilot top-fermenting process was used as a raw material for the first time. The disruption effectiveness of autolysis (98%) was higher than that of the mechanical methods (80%), as well as the cleavage of amino acids from the cell protein (307, 155 and 115 mg per g yeast extract for autolysis, sonotrode and cell mill). The proteinogenic amino acid release profiles were dependent upon the disruption methods. The greater the released quantity of an amino acid during autolysis, the more the mean value fluctuated in the prepared yeast extract. Protein size fractionation of the extract using electrophoresis showed differences ranging between 1.5 and 95 kDa. All yeast extracts evidenced good nutritional potential according to FAO/WHO standards. The calculated data showed that the manufacturing method has a big impact on the proteinogenic composition of a yeast extract and the spent yeast TUM 68 used in this study can yield a protein-rich yeast extract.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Vieira F, Carvalho J, Pinto E, Cunha S, Almeida A, Ferreira I (2016) Nutritive value, antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds profile of brewer’s spent yeast extract. J Food Compos Anal 52:44–51

Cefalu WT, Hu FB (2004) Role of chromium in human health and in diabetes. Diabetes Care 27(11):2741–2751

Ding WJ, Qian QF, Hou XL, Feng WY, Chai ZF (2000) Determination of chromium combined with DNA, RNA and proteins in chromium-rich brewer’s yeast by NAA. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 244(2):259–262

Saksinchai S, Suphantharika M, Verduyn C (2001) Application of simple yeast extract from brewer’s yeast for growth ans sporolation of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki: a physiological study. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 17:307–316

Rakin M, VukasinoViC M, Siler-Marinkovic S, Maksimovic M (2007) Contribution of lactic acid fermentation to improved nutritive quality vegetable juices enriched with brewer’s yeast autolysate. Food Chem 100(2):599–602

Geciova J, Bury D, Jelen P (2002) Methods for disruption of microbial cells for potential use in the dairy industry—a review. Int Dairy J 12:541–553

Ferreira IMPLVO, Pinho O, Vieira E, Tavarela JG (2010) Brewer’s Saccharomyces yeast biomass: characteristics and potential applications. Trends Food Sci Technol 21:77–84

Rezanka T, Matoulkova D, Kolouchova I, Masak J, Viden I, Sigler K (2015) Extraction of brewer’s yeasts using different methods of cell disruption for practical biodiesel production. Folia Microbiol 60(3):225–234

Vieira E, Brandão T, Ferreira IMPLVO (2013) Evaluation of brewer’s spent yeast to produce flavor enhancer nucleotides: influence of serial repitching. J Agric Food Chem 61:8724–8729

Amorim M, Pereira JO, Gomes D, Pereira CD, Pinheiro H, Pintado M (2016) Nutritional ingredients from spent brewer’s yeast obtained by hydrolysis and selective membrane filtration integrated in a pilot process. J Food Eng 185:42–47

Berlowska J, Dudkiewicz-Kołodziejska M, Pawlikowska E, Pielech-Przybylska K, Balcerek M, Czysowska A, Kregiel D (2017) Utilization of post-fermentation yeasts for yeast extract production by autolysis: the effect of yeast strain and saponin from Quillaja saponaria. J Inst Brew 123:396–401

Caballero-Cordoba GM, Sgarbieri VC (2000) Nutritional and toxicological evaluation of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) biomass and a yeast protein concentrate. J Sci Food Agric 80:341–351

Podpora B, Świderski F, Sadowska A, Piotrowska A, Rakowska R (2015) Spent brewer’s yeast autolysates as a new and valuable component of functional food and dietary supplements. J Food Process Technol 6(12):1

Fuke S, Konosu S (1991) Taste-active components in some foods: a review of Japanese research. Physiol Behav 49:863–868

Münch P (1999) Aromastoffe in thermisch behandelten Hefeextrakten. Verlag Dr. Hut, München

Münch P, Schieberle P (1998) Quantitative studies on the formation of key odorants in thermally treated yeast extracts using stable isotope dilution assays. J Agric Food Chem 46:4695–4701

European Parliament and the Council (2008) Regulation (EC) No 1334/2008 on flavourings and certain food ingredients with flavouring properties for use in and on foods and amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 1601/91, Regulations (EC) No 2232/96 and (EC) No 110/2008 and Directive 2000/13/EC

Chae HJ, Joo H, In MJ (2001) Utilization of brewer’s yeast cells for the production of food-grade yeast extract. Part 1: effects of different enzymatic treatments on solid and protein recovery and flavour characteristics. Biores Technol 76(3):253–258

Reeds PJ (2000) Dispensable and indispensable amino acids for humans. J Nutr 130(7):1835–1840

World Health Organization (2007) Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition Report of a joint FAO/WHO/UNU expert consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 935. United Nations University

Dhakal R, Bajpai VK, Baek KH (2012) Production of GABA. Braz J Microbiol 43:1230–1241

Casey GP, Magnus CA, Ingledew WM (1984) High-gravity brewing: effects of nutrition on yeast composition, fermentative ability, and alcohol production. Appl Environ Microbiol 48(3):639–664

Ingledew WM, Sosulski FW, Magnus CA (1986) An assessment of yeast foods and their utility in brewing and enology. Am Soc Brew Chem 44(4):166–170

Procopio S, Krause D, Hofmann T, Becker T (2013) Significant amino acids in aroma compound profiling during yeast fermentation analyzed by PLS regression. LWT Food Sci Technol 51:423–432

Meullemiestre A, Breil C, Abert-Vian M, Chemat F (2016) Microwave, ultrasound, thermal treatments, and bead milling as intensification techniques for extraction of lipids from oleaginous Yarrowia lipolytica yeast for a biojetfuel application. Biores Technol 211:190–199

Bystryak S, Santockyte R, Peshkovsky AS (2015) Cell disruption of S. cerevisiae by scalable high-intensity ultrasound. Biochem Eng J 99:99–106

Sommer R (1998) Yeast extracts: production, properties and components. Food Aust 50(4):181–183

Bronn WK (1996) Hefe und Hefeextrakte. In: Heiss R (ed) Lebensmitteltechnologie. Biotechnologische, chemische, mechanische, und thermische Verfahren der Lebensmittelverarbeitung. Springer, Berlin, pp 336–343

Kim KS, Yun HS (2006) Production of soluble beta-glucan from the cell wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enzyme Microb Technol 39:496–500

Apar DK, Özbek B (2008) Protein releasing kinetics of bakers’ yeast cells by ultrasound. Chem Biochem Eng Q 22(1):113–118

De Nicola R, Hall N, Melville S, Walker G (2009) Influence of zinc on distiller’s yeast: cellular accumulation of zinc and impact on spirit congeners. J Inst Brew 115(3):265–271

Wilson WA, Hughes WE, Tomamichel W, Roach PJ (2004) Increased glycogen storage in yeast results in less branched glycogen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 320(2):416–423

Alexandre H (2011) 2.45 Autolysis of yeasts. Comprehensive biotechnology, 2nd edn, vol 2. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 641–649

Annemüller G, Manger HJ (2013) Gärung und Reifung des Bieres 2. überarbeitete Auflage 2013 edn. VLB Berlin, Berlin

Manas P, Pagan R (2005) A review—microbial inactivation by new technologies of food. J Appl Microbiol 98:1387–1399

López-Solís R, Duarte-Venegas C, Meza-Candia M, Barrio-Galán R, Peña-Neira A, Medel-Marabolí M, Obreque-Slier E (2017) Great diversity among commercial inactive dry-yeast based products. Food Chem 219:282–289

Spearman M, Chan S, Jung V, Kowbel V, Mendoza M, Miranda V, Butler M (2016) Components of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) extract as defined media additives that support the growth and productivity of CHO cells. J Biotechnol 233:129–142

Vieira EF, Melo A, Ferreira IMPLVO (2017) Autolysis of intracellular content of Brewer’s spent yeast to maximize ACE-inhibitory and antioxidant activities. LWT Food Sci Technol 82:255–259

Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (2018) Durchführungsverordnung (EG) Nr. 889/2008 mit Durchführungsvorschriften zur Verordnung (EG) Nr. 834/2007 des Rates über die ökologische/biologische Produktion und die Kennzeichnung von ökologischen/biologischen Erzeugnissen ABl. Nr. L 250 vom 18.09.08, S1

Quain DE (2006) Yeast supply and propagation in brewing. In: Brewing: new technologies. Woodhead, Cambridge, pp 167–182

Research Center Weihenstpehan (2018) Stammbeschreibung LeoBavaricus—TUM 68® Saccharomyces cerevisiae, obergärige Weizenbierhefe. http://www.blq-weihenstephan.de/tum-hefen/hefen-und-bakterien.html. Accessed 1 Apr 2018

Pfenninger H (1996) MEBAK Brautechnische Analysemethoden Band 3. Selbstverlag der MEBAK, Freising

Hutzler M (2009) Entwicklung und Optimierung von Methoden zur Identifizierung und Differenzierung von getränkerelevanten Hefen. Technischen Universität, München

Back W (2008) Ausgewählte Kapitel der Brauereitechnologie. Fachverlag Hans Carl GmbH, Nürnberg

Biotecon Diagnostics (2018) Foodproof beer screening kit. https://www.bc-diagnostics.com/products/kits/real-time-pcr/spoilage-organisms/foodproof-beer-screening-kit/. Accessed 1 Apr 2018

Jazwinski SM (1990) Preparation of extracts from yeast. Methods Enzymol 182:154–174

Jacob F (2012) MEBAK Brautechnische Analysemethoden Würze Bier Biermischgetränke. Selbstverlag der MEBAK, Freising-Weihenstephan

Naumann C, Bassler R, Seibold R, Barth C (1976) Methodenbuch Band 3, die chemische Untersuchung von Futtermitteln. VDLUFA, Darmstadt

Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254

Agilent (2018) Protein analysis kits—details & specifications. https://www.genomics.agilent.com/article.jsp?crumbAction=push&pageId=1644. Accessed 1 Apr 2018

Currie JA, Dunnill P, Lilly MD (1972) Release of protein from bakers’ yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) by disruption in an industrial agitator mill. Biotechnol Bioeng 14:725–736

James CJ, Coakley WT, Hughes DE (1972) Kinetics of Protein Release from Yeast Sonicated in Batch and Flow Systems at 20 kHz. Biotechnol Bioeng 14:33–42

Wu T, Yu X, Hu A, Zhang L, Jin Y, Abid M (2015) Ultrasonic disruption of yeast cells: underlying mechanism and effects of processing parameters. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 28:59–65

Lei H, Zheng L, Zhao H, Zhao M (2013) Effects of worts treated with proteases on the assimilation of free amino acids and fermentation performance of lager yeast. Int J Food Microbiol 161:76–83

Slaughter JC, Nomura T (1992) Activity of the vacuolar proteases of yeast and the significance of the cytosolic protease inhibitors during the postfermentation decline phase. J Inst Brew 98 (4):335–338

Hans MA, Heinzle E, Wittmann C (2001) Quantification of intracellular amino acids in batch cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 56:776–779

Martinezforce E, Benitez T (1995) Effects of varying media, temperature, and growth-rates on, the intracellular concentrations of yeast amino-acids. Biotechnol Prog 11 (4):386–392

Schieberle P (1990) The role of free amino acids present in yeast as precursors of the odorants 2-acetyl-l-pyrroline and 2-acetyltetrahydropyridine in wheat bread crust. Zeitschrift für Lebensmitteluntersuchung Forschung 191:206–209

Behalova B, Beran K (1979) Activation of proteolytic enzymes during autolysis of disintegrated bakers-yeast. Folia Microbiol 24(6):455–461

Kieliszek M, Blazejak S, Bzducha-Wrobel A (2015) Influence of selenium content in the culture medium on protein profile of yeast cells Candida utilis ATCC 9950. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015:659750. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/659750

Kieliszek M, Błażejak S, Bzducha-Wróbel A, Kot AM (2018) Effect of selenium on lipid and amino acid metabolism in yeast cells. Biol Trace Element Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-018-1342-x

Diana M, Rafecas M, Quílez J (2014) Free amino acids, acrylamide and biogenic amines in gamma-aminobutyric acid enriched sourdough and commercial breads. J Cereal Sci 60:639–644

Yilmaz C, Gokmen V (2018) Comparative evaluation of the formations of gamma-aminobutyric acid and other bioactive amines during unhopped wort fermentation. J Food Process Preserv 42(1):7

Gong J, Huang J, Xiao G, You Y, Yuan H, Chen F, Liu S, Mao J, Li B (2017) Determination of γ-aminobutyric acid in Chinese rice wines and its evolution during fermentation. Inst Brew Distill 123:417–422

Shelp BJ, Bown AW, McLean MD (1999) Metabolism and functions of gamma-aminobutyric acid. Trends Plant Sci 4(11):446–452

Masuda K, Guo X, Uryu N, Hagiwara T, Watabe S (2008) Isolation of marine yeasts collected from the Pacific Ocean showing a high production of γ-aminobutyric acid. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 72(12):3265–3272

G-Biosciences (2018) Protein Assays Technical Guide & handbook. https://info2.gbiosciences.com/complete-protein-assay-guide. Accessed 1 Apr 2018

Narziß L, Back W, Gastl M, Zarnkow M (2017) Abriss der Bierbrauerei, 8. vollständig überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim

Gibson BR (2011) 125th anniversary review: improvement of higher gravity brewery fermentation via wort enrichment and supplementation. J Inst Brew 117(3):268–284

Ge L, Wang X-T, Tan SN, Tsai HH, Yong JWH, Hua L (2010) A novel method of protein extraction from yeast using ionic liquid solution. Talanta 81:1861–1864

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Friedrich Felix Jacob, Mathias Hutzler and Frank-Jürgen Methner declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethics requirements

The authors Friedrich Felix Jacob, Mathias Hutzler and Frank-Jürgen Methner hereby confirm that this manuscript is performed according and follows the COPE guidelines and has not already been published nor is it under consideration for publication elsewhere. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jacob, F.F., Hutzler, M. & Methner, FJ. Comparison of various industrially applicable disruption methods to produce yeast extract using spent yeast from top-fermenting beer production: influence on amino acid and protein content. Eur Food Res Technol 245, 95–109 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-018-3143-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-018-3143-z