Abstract

The participation of the nitroethene and its α-substituted analogs as model nitrofunctionalized monomers, and (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone and methyl vinyl ether as initiators in the polymerization reactions, has been analyzed in the framework of the density functional theory calculations at the M06-2X(PCM)/6-311 + G(d) level. Our computational study suggests the zwitterionic mechanism of the polymerization process. The exploration of the nature of critical structures shows that the first reaction stage exhibits evidently polar nature, whereas additions of further nitroalkene molecules to the polynitroalkyl molecular system formed should be considered as moderate polar processes. The more detailed view on the molecular transformations gives analysis based on the bonding evolution theory. This study shows that the case of polymerization reaction between nitroethene and (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone allows for distinguishing eleven topologically different phases, while, in the case of polymerization reaction nitroethene and methyl vinyl ether, we can distinguish nine different phases.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

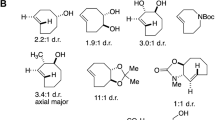

Poly-nitro compounds are widely used as highly effective propellants [1]. The general method for their preparation is the polymerization of conjugated nitroalkenes (CNA) [2]. However, not all nitroalkenes can be used as raw material in this kind of synthesis. In particular, it is much easier for a retro-nitroaldol reaction to take place with 2-aryl-1-EWG-1-nitroethenes, and addition reactions only apply to some highly reactive nucleophilic reagents such as azide ion [3], cyclopentadiene [4] and N-methylazomethine ylide [5]. 2-Aryl-1-nitroethenes of the retro-nitroaldol reaction are not participated and, at the same time, are effective components of addition to dienes [6, 7] and three-atom components (TACs) [8] such as nitrones [9, 10], azides [11] and nitrile N-oxides [12,13,14]. At the same time, there are no reports about their polymerization. On the other hand, parent nitroethene (1a) [15] and its simple 1-substituted analogs such as 2-nitroprop-1-ene (1b) [15, 16], 1-fluoro-1-nitroethene (1c) [17], 1-chloro-1-nitroethene (1d) [18, 19] or 1-bromo-1-nitroethene (1e) [20] tend to form high molecular systems (Scheme 1). The initiators described for this type of polymerization are inorganic bases [15, 16]. The disadvantage of their use is the quite rapid and sometimes explosive polymerization process. The milder CNA polymerization processes have not been the subject of detailed research work so far.

Huisgen and Mloston described the reaction of nitroethene with 2,2,4,4-tetramethyl-3-thioxocyclobutanone S-methylide in 1992 [21]. In this reaction, the cycloadduct expected by the authors [3 + 2] is formed with relatively low yield. Instead, significant amounts of nitroethene polymer were found in the post-reaction mass. This prompted the authors to hypothesize that the first stage of the analyzed reaction is the formation of a zwitterionic adduct (ZA), which, as a labile intermediate, may on competitive paths (a) cyclize to nitrothiolate and (b) become the initiator of mild nitroethene polymerization (Scheme 2). Recent studies have confirmed the presence of the zwitterionic intermediate in the environment of the described reaction [22].

In recent years, it has been observed that certain amounts of nitropolymers also appear in post-reaction masses [3 + 2] cycloaddition of nitroethene and its 1-substituted analogs (1a–e) with arylonitrones, in twofold to fourfold molar excess of nitroalkene [23,24,25].

Analysis of the literature data [26,27,28] also showed that, in the case of the Hetero Diels–Alder reaction with the participation of nitroalkenes and EDG-substituted unsaturated compounds (such as alkyl vinyl ethers), the formation of a zwitterionic intermediate may compete with the addition process (Scheme 3). These intermediates, by analogy with the scenario described above, could be initiators for CNA polymerization processes.

The above observations give reason to believe that some unsaturated nucleophilic reagents may be effective initiators of mild, zwitterionic polymerization of simple CNAs. As part of this work, we decided to shed light on the molecular mechanism as well as the kinetic and thermodynamic aspects of such transformations. For this purpose, we decided to use data for quantum chemical calculations based on density functional theory (DFT). The obtained results should aid understanding of the nature of transformations taking place in the course of the analyzed processes and thus allow for their rational design on a laboratory scale.

2 Computational details

All quantum chemical calculations were performed using ‘Prometheus’ cluster (CYFRONET regional computational center). The M06-2X functional [29] included in the GAUSSIAN 09 package [30] and the 6-311 + G(d) basis set including both diffuse and polarization functions for all relevant atoms was used. All localized stationary points have been characterized using vibrational analysis. It was found that starting molecules, intermediates and products had positive Hessian matrices. For the contrast, all transition states (TS) showed only one negative eigenvalue in their Hessian matrices. For all optimized transition states, intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations have been performed. The presence of the solvent (nitromethane) in the reaction environment has been included using IEFPCM algorithm [31].

The topological analyses of the electron localization function (ELF) [32,33,34] were performed with the TopMod [35] program using the corresponding M06-2X(PCM)/6-311 + G(d) monodeterminantal wavefunctions. ELF calculations were computed over a grid spacing of 0.1 a.u. for each structure, and ELF localization domains were obtained for an ELF value of 0.75. For the bonding evolution theory (BET) [36] studies, the topological analysis of the ELF along the IRC was performed for a total of 136 nuclear configurations for reaction from substrates 1a, 2 to product Z1A and with second molecule of 1a to product Z2A. For the reaction 1a with 3 to product Z1B and reaction with second molecule of 1a leading to Z2B, the topological analysis of the ELF along the IRC was performed for a total of 122 nuclear configuration. BET applies Thom’s catastrophe theory (CT) concepts [37,38,39] to the topological analysis of the gradient field of the ELF [34].

The electron localization function (ELF) [34] is a relative measure of the same spin pair density local distribution, i.e., the Pauli repulsion, in the context of monodeterminantal wavefunctions. High values of the ELF are associated with high-probability regions for electron pairing in the spirit of Lewis structures. The analysis of the gradient field or topology of ELF [32, 33] renders a partition of the molecular space into non-overlapping volumes or basins that could be associated with entities and concepts of chemical significance as atomic cores and valence regions (e.g., bonds or lone pairs). Valence basins are in turn classified depending of the number of core basins with which they share a boundary (i.e., the so-called synaptic order) [32, 33]. A complete population analysis can be performed based on the integration of the one- and two-electron density probabilities in the ELF basins.

3 Results and discussion

We adopted nitroethene (1a) and a group of its substituted analogs as model CNA, as illustrated in Scheme 1. As initiators of the polymerization process, we tested (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone (2) and methyl vinyl ether (3) (Scheme 4). Within the scope of theoretical studies, we examined the pathways leading to the formation of primary zwitterionic intermediates as a result of the addition of CNA to the nucleophile and then examined the energy profiles of processes involving the addition of four subsequent CNA molecules. In order to better understand the molecular mechanism of these reactions, a BET study for the key stages of the polymerization reactions nitroethene (1a) with (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone (2) and methyl vinyl ether (3) was employed.

3.1 Energetical profiles and key structures for reaction involving (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone

The general scheme of the reaction of (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone 2 with nitroethene 1a is illustrated in Scheme 5. The M06-2X(PCM)/6-311 + G(d) calculations indicate that the first stage of the process is the formation of the molecular pre-reaction complex (MC1A) (Fig. 1, Table 1). This is due to a decrease in the enthalpy of the reacting system by 2 kcal/mol. It should be noted that this formation causes a strong reduction in entropy, so the free Gibbs energy of MC1A creation is positive. This excludes the possibility of the MC1A complex in the form of a stable intermediate. Within MC1A, both of its components approach each other in such a way that the distance between the reaction centers O1 and C4 decreases below 3.5 Å. It is not a CT complex (GEDT value is equal to 0.00e). Further conversion of the pre-reaction complex is effected through transient TS1A. Enthalpy of TS1A is 7.5 kcal/mol higher than that of individual reagents. At the same time, the entropic factor causes the Gibbs free energy of the activation to be slightly higher, reaching 20 kcal/mol. Within TS1A, the distance between the reaction centers O1 and C4 decreases to 1.838 Å. This structure is clearly polar, as demonstrated by the value of the GEDT index (0.57 e). Further approximation of the O1 and C4 reaction centers leads to the formation of the Z1A intermediate. Within Z1A, the distance O1–C4 is 1.504 Å. This intermediate is zwitterion, which confirms the value of GEDT (0.81 e). It is not a thermodynamically stable structure and can easily undergo chemical conversion by addition of a second nitroethene molecule. This process is initiated by the formation of the MC2A molecular complex. This stage is carried out without overcoming the activation barrier and is associated with a decrease in enthalpy of the reacting system by 4.4 kcal/mol. The nature of MC2A is very similar to that of the MC1A complex. The gradual approach of reaction centers in this complex leads to transient TS2A. This involves overcoming a much lower energy barrier than in the case of the first stage of the analyzed process. Within TS2A, the key distance C5–C6 reaches 2.274 Å. The polarity of TS2A is smaller than TS1A (GEDT = 0.19 e). Further movement of the reacting system along the coordinate of the reaction leads to the formation of the Z2A molecule. It should be emphasized that the transformation of MC1A into Z2A is irreversible from thermodynamic point of view. Z2A can add further nitroethene molecules through transient states of a nature (distances between reaction centers equal 2.26–2.29 Å; GEDT is less than 0.2 e) very similar to that of TS2A. The sequence of several such transformations is illustrated in Scheme 5. It should be emphasized that, each time, the attachment of a further nitroethene molecule is easy from a kinetic point of view and, at the same time, beneficial from the thermodynamic point of view of the whole process because it is associated with a decrease in the Gibbs free energy of the reacting system by 9-12 kcal/mol.

Next, we verified the susceptibility of other CNAs mentioned on Scheme 1 to polymerization initiated by nitrone 2. It was discovered that each of these processes is carried out according to a very similar mechanism as in the case of nitroethene. The first stage is always the formation of a labile, zwitterionic adduct, to which another CNA molecule may easily be added.

3.2 BET study of the polymerization reaction between nitroethene 1a and (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone 2

In order to characterize the bonding changes along the polymerization reaction of nitroethene (1a) and (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone (2), a BET study of the key stages of this reaction was carried out. In the first stage of this reaction, we stand out six different topological phases (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Phase I, 2.43 Å ≤ d(O1–N2) < 2.45 Å, 2.47 Å ≥ d(N2–C3) > 2.46 Å, 5.29 Å ≥ d(O1–C4) > 3.94 Å and 2.50 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.54 Å, begins at MC1A, which is a discontinuous point of the IRC from TS1A toward the intermediate Z1A. The ELF topological analysis of MC1A divulges slight changes in the ELF valence basins electron populations of substrates 1a and 2 (see Table 2). The population of V(O1,N2), V(N2,C3) and V(C4,C5) disynaptic basins progressively increases, but population of V’(C4,C5) disynaptic basin remains unchanged.

At P1A, Phase II begins, 2.45 Å ≤ d(O1–N2) < 2.54 Å, 2.46 Å ≥ d(N2–C3) > 2.45 Å, 3.94 Å ≥ d(O1–C4) > 3.25 Å and 2.54 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.67 Å, which is described by a cusp C catastrophe. At this point, the first most relevant change along the reaction path takes place; the two V(C4,C5) and V’(C4,C5) disynaptic basins have merged into a V(C4,C5) disynaptic basin integrating 3.44e. This change is related to the double-bond rupture in the nitroethene 1a molecule, with a demand energy cost of 7.4 kcal/mol (Table 2). In this phase, we can find the transition state (TS1A) of the reaction of 1a and 2: d(O1–N2) = 2.50 Å, d(N2–C3) = 2.45 Å, d(O1–C4) = 3.47 Å and d(C4–C5) = 2.61 Å.

Phase III, d(O1–N2) = 2.54 Å, d(N2–C3) = 2.45 Å, 3.25 Å ≥ d(O1–C4) > 3.19 Å and 2.67 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.68 Å, starts at P2A. This point is characterized by a fold F† catastrophe. In this phase, we observed the formation of a new V(C5) monosynaptic basin integrating 0.55e and decreased the value of V(C4,C5) disynaptic basin, which in this phase integrating 2.84e.

At P3A begins Phase IV, 2.54 Å ≤ d(O1–N2) < 2.56 Å, d(N2–C3) = 2.45 Å, 3.19 Å ≥ d(O1–C4) > 3.08 Å and 2.68 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.71 Å. This point is characterized by fold F† catastrophe, in which the V(C5) monosynaptic basin divides into two V(C5) and V’(C5) monosynaptic basins integrating 0.60e and 0.31e, respectively.

At Phase V, 2.56 Å ≤ d(O1–N2) < 2.58 Å, d(N2–C3) = 2.45 Å, 3.08 Å ≥ d(O1–C4) > 2.93 Å and 2.71 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.74 Å, which begins at P4A, the next significant topological change along the reaction path takes place. At this phase, established by a cusp C catastrophe the new V(O1,C4) disynaptic basin has been formed with initial population of 0.77e (Table 2). At this phase, we also observed that the population of V(O1) and V’(O1) monosynaptic basins and V(C4,C5) disynaptic basin progressively decreased, integrating 2.60e, 2.76e and 2.33e, respectively.

Finally, the last Phase VI, 2.58 Å ≤ d(O1–N2) < 2.57 Å, d(N2–C3) = 2.45 Å, 2.93 Å ≥ d(O1–C4) > 2.87 Å and 2.74 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.75 Å, is located between points P5A and Z1A. Here, characterized by cusp C† catastrophe, a disynaptic basin V(N2,C3) integrating 3.83e is divided into two disynaptic basins V(N2,C3) and V’(N2,C3) integrating 1.89e and 1.94e, respectively.

In turn, addition of the second molecule of 1a to Z1A can be characterized by five different topological phases (Table 3).

Phase VII, 2.75 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.76 Å, 5.57 Å ≥ d(C5–C6) > 4.69 Å and 2.50 Å ≤ d(C6–C7) < 2.52 Å, starts at MC2A. This point is the interrupt of the IRC from TS2A toward the product Z2A. The ELF picture of MC2A represents small changes in ELF valence basin electron populations of Z1A and 1a. ELF analysis of MC2A shows a slight increase in the population of V(O1,C4) and V(C6,C7) disynaptic basins. On the other hand, the population of V(C4,C5) and V’(C6,C7) disynaptic basins progressively decrease.

At Phase VIII, d(C4–C5) = 2.76 Å, 4.69 Å ≥ d(C5–C6) > 4.47 Å and 2.52 Å ≤ d(C6–C7) < 2.54 Å, which begins at P6A, the first topological change along the reaction path takes place. In this point, described by a fold F catastrophe, we observed the disappearance a V’(C5) monosynaptic basin and the value of the V(C5) monosynaptic basin increased, integrating 0.64e (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Phase IX, 2.76 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.79 Å, 4.47 Å ≥ d(C5–C6) > 3.94 Å and 2.54 Å ≤ d(C6–C7) < 2.63 Å, begins at P7A and is featured by cusp C catastrophe. In this phase, the V’(C6,C7) disynaptic basin is disappearance and the value of the V(C6,C7) disynaptic basin increases, integrating 3.49e. In this phase, there is a transition state (TS2A) of the analyzed reaction: d(C4–C5) = 2.77 Å, d(C5–C6) = 4.30 Å and d(C6–C7) = 2.56 Å.

P8A, 2.79 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.81 Å, 3.94 Å ≥ d(C5–C6) > 3.76 Å and 2.63 Å ≤ d(C6–C7) < 2.68 Å, commences the Phase X, which is described by cusp C catastrophe. At this phase, the V(C5) monosynaptic basin disappears and a new V(C5,C6) disynaptic basin integrating 1.11e is formed. This new V(C5,C6) disynaptic basin is associated with the formation a sigma bond between C5 and C6 atoms.

At last, we distinguish the Phase XI, which begins at P9A, 2.81 Å ≤ d(C4–C5) < 2.85 Å, 3.76 Å ≥ d(C5–C6) > 2.92 Å and 2.68 Å ≤ d(C6––C7) < 2.81 Å. In this phase, located between P9A and Z2A, described by fold F† catastrophe, we noticed that new V(C7) and V’(C7) monosynaptic basins integrating 0.50e and 0.24e are established at P9A. These changes are related to a high energy cost of − 16.2 kcal/mol−1 (Table 3).

In this section, the bonding changes arising from the BET study and their associated energy changes along the key stages of polymerization reaction between nitroethene 1a and (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone 2 are summarized and described. The sequential bonding changes received from the BET analysis of the analyzed reaction are shown in Table 4, together with a simplified representation of the molecular mechanism by ELF-based Lewis-like structures. From this BET study, some appealing conclusions can be obtained: (i) the molecular mechanism of the analyzed polymerization reaction 1a and 2 can topologically characterize eleven different phases, which have been grouped into five Groups A-E and linked to significant chemical events (Table 4); (ii) Group A, containing Phases I and II, in which the C4–C5 double bond breaks, leading to the formation of a C5 pseudoradical center. In Phase II, the transition state of reaction 1a with 2 is found; (iii) Group B, containing only Phase V, in which the new O1–C4 single bond is formed; (iv) Group C, also contains only one Phase VI, which is associated with the formation of a N2–C3 double bond; (v) Phases VII–IX belong to the Group D and are associated with rupture of the C6–C7 double bond in the second molecule of 1a; (vi) the last group, containing Phases X–XI in which the new C5–C6 single bond and C7 pseudoradical center are formed.

3.3 Energetical profiles and key structures for reaction involving methyl vinyl ether

CNA polymerization initiated by ether 3 is generally carried out in a rather similar way to the reaction involving nitrone 2. The general scheme of this transformation is shown in Scheme 6. The first stage of the process is that of formation of the molecular pre-reaction complex (MC1B) (Fig. 4 and Table 5). Like MC1A, this structure is not a CT complex, and the reaction centers within it are approaching a distance of 3.822 Å. Its conversion to zwitterion Z1B is carried out through transition state TS1B. It should be noted that the enthalpy needed to achieve TS1B is almost double required for TS1A. This is understandable, given that the global nucleophilicity of nitrone 2 is 3.64 eV, while for ether 3 it is much less, at 3.18 eV. Within TS1B, the distance between reaction centers is 1.948 Å. The kinetics of attaching subsequent nitroethene molecules to zwitterion Z1B is similar to that involved in the 1a + 2 reaction. In particular, subsequent activation barriers for the sequence of addition of several subsequent 1a molecules do not exceed several kcal/mol. Within the analyzed TSs, reaction centers are separated from each other by a distance of approximately 2.3 Å.

Next, we verified the susceptibility of other CNAs mentioned in Scheme 1 to polymerization initiated by ether 3. It was discovered that each of these processes is carried out via a very similar mechanism to that in the case of nitroethene. The first stage is always the formation of a labile, zwitterionic adduct, to which another CNA molecule may easily be added.

3.4 BET study of the polymerization reaction between nitroethene 1a and methyl vinyl ether 3

The BET study of the addition of the first molecule of nitroethene 1a to methyl vinyl ether 3 indicates that this reaction is topologically characterized by five different phases. The population of the most significant valence basins of the selected points of the IRC, defining the different topological phases, is included in Table 6.

Phase I, 2.51 Å ≤ d(C1–C2) < 2.54 Å, 5.82 Å ≥ d(C1–C3) > 4.20 Å and 2.50 Å ≤ d(C3–C4) < 2.55 Å, begins at MC1B, which is the first structure of the reaction path between substrates: 1a, 3 and TS1B. In this phase, only small changes in the populations of the valence basins of MC1B compared with 1a and 3 are observed. The population of V’(C1,C2) and V(C3,C4) disynaptic basin progressively increases as well as the population of V(C1,C2) and V’(C3,C4) progressively decreased.

The next Phase II, d(C1–C2) = 2.54 Å, 4.20 Å ≥ d(C1–C3) > 4.14 Å and 2.55 Å ≤ d(C3–C4) < 2.56 Å, starts at P1B. At this point, described by the cusp C catastrophe, the first noticeable topological change along the IRC occurs. In this phase, the two V(C3,C4) and V’(C3,C4) disynaptic basins are merged into one V(C3,C4) disynaptic basin, integrating 3.41e (Table 6 and Fig. 5). This topological change is associated with the rupture of the C3–C4 double bond in the nitroethene (2) molecule.

Phase III, 2.54 Å ≤ d(C1–C2) < 2.61 Å, 4.14 Å ≥ d(C1–C3) > 3.62 Å and 2.56 Å ≤ d(C3–C4) < 2.66 Å, begins at P2B. This point is characterized by a cusp C catastrophe. At P2B, the two V(C1–C2) and V’(C1,C2) disynaptic basins are integrated into one V(C1,C2) disynaptic basin, integrating 3.35e. In this phase, we observed the rupture of the C1–C2 double bond in the methyl vinyl ether (3) molecule. In this phase, we find the transition state (TS1B) of studied reaction: d(C1–C2) = 2.60 Å, d(C1–C3) = 3.68 Å and d(C3–C4) = 2.65 Å (Table 6).

P3B starts Phase IV, 2.61 Å ≤ d(C1–C2) < 2.65 Å, 3.62 Å ≥ d(C1–C3) > 3.42 Å and 2.66 Å ≤ d(C3–C4) < 2.71 Å. In this phase, the next most relevant topological change along the reaction path is observed. At this point, a new V(C1,C3) disynaptic basin integrating 0.59e is created. In this phase, we also observed that the value of the V(C1,C2) and V(C3,C4) disynaptic basins decreased, 2.91e and 3.14, respectively. This topological change can be associated with the formation of the C1–C3 single bond, taking place at a C1–C3 distance of 3.617 Å. These changes are related to a high energy cost of 13.4 kcal/mol (Table 6).

Phase V, the last phase, 2.65 Å ≤ d(C1–C2) < 2.73 Å, 3.42 Å ≥ d(C1–C3) > 3.02 Å and 2.71 Å ≤ d(C3–C4) < 2.79 Å, starts at P4B and ends at the zwitterion product Z1B and is described by a fold F† catastrophe. At this phase, the last important change along the reaction path takes place: A new V(C4) monosynaptic basin is created integrating 0.53e, which is related to the formation of a pseudoradical center on the C4 atom.

In turn, the reaction zwitterion Z1B with second molecule of nitroethene 1a can be characterized by four different phases (Table 7).

Phase VI, 2.80 Å ≤ d(C3–C4) < 2.81 Å, 5.20 Å ≥ d(C4–C5) > 4.41 Å and 2.51 Å ≤ d(C5–C6) < 2.55 Å, begins at the MC2B, which is the first structure of the reaction path between Z1B + 1a and TS2B. The ELF picture of MC2B represents small changes in ELF valence basin electron populations of Z1B and 1a. ELF analysis of MC2B shows a slight increase in the population of V(C5,C6), V’(C5,C6) disynaptic basin, as well as the population of V(C3,C4) disynaptic basin progressively decreases.

At P5B, Phase VII begins, 2.81 Å ≤ d(C3–C4) < 2.83 Å, 4.41 Å ≥ d(C4–C5) > 3.89 Å and 2.55 Å ≤ d(C5–C6) < 2.65 Å. At this phase, established by cusp C catastrophe, the V’(C5,C6) disynaptic basin disappears and the valence basin electron population of V(C5,C6) disynaptic basin increased, integrating 3.45e. This topological change can be related to the rupture of C5–C6 double bond, taking place at a C5–C6 distance of 2.548 Å. In this phase, there is a transition state (TS2B) of the attachment of the second nitroethene (1a) molecule to Z1B: d(C3–C4) = 2.81 Å, d(C4–C5) = 4.35 Å and d(C5–C6) = 2.56 Å (Table 7 and Fig. 6).

Phase VIII, 2.83 Å ≤ d(C3–C4) < 2.85 Å, 3.89 Å ≥ d(C4–C5) > 3.71 Å and 2.65 Å ≤ d(C5–C6) < 2.69 Å, starts at P6B. At this point, characterized by a fold F catastrophe, the V(C4) monosynaptic basin present at P5B has disappeared and a new V(C4,C5) disynaptic basin integrating 1.07e is formed. This change can be related to the formation of a new single bond between C4 and C5 molecules, which is taking place at a C4–C5 distance of 3.885 Å.

At last, Phase IX, 2.85 Å ≤ d(C3–C4) < 2.87 Å, 3.71 Å ≥ d(C4–C5) > 2.92 Å and 2.69 Å ≤ d(C5–C6) < 2.81 Å, begins at P7B and ends at the Z2B. At P7, the new V(C6) monosynaptic basin integrating 0.52e is created and the integration of V(C5,C6) disynaptic basin slightly decreased. In the Z2B molecule, we observed the formation of a second V’(C6) monosynaptic basin integrating 0.46e.

Based on the BET analysis of the polymerization reaction between nitroethene (1a) and methyl vinyl ether (3), some appealing conclusions can be drawn: (i) the molecular mechanism of the key stages of the polymerization reaction 1a with 3 can be topologically characterized by nine different phases, which have been grouped into five groups A–E and linked to significant chemical events (see Table e3–e4); (ii) Group A, containing Phase I, is associated with the rupture of the C3–C4 double bond in nitroethene (1a) molecule; in Group B, we observed the breaking C1–C2 double bond in methyl vinyl ether (3) molecule; (iii) Group C comprises Phases III–V, in which we observed the formation of a C1–C3 single bond and pseudoradical center at C4 atom; (iv) Group D, containing Phases VI and VII, is associated with connecting the second molecule of nitroethene (1a) and rupture of the C5–C6 double bond; (v) Group E, the last group, comprises Phases VIII and IX, in which we observed the formation of a C4–C5 single bond and C6 pseudoradical center (Table 8).

4 Conclusion

The DFT computational study shed light on the kinetic aspects as well as the molecular mechanism of zwitterionic polymerization of simple conjugated nitroalkenes. These reactions can proceed under relatively mild conditions. The exploration of reaction profiles shows that the first reaction stage exhibits evidently polar nature, whereas additions of further CNA molecules to the polynitroalkyl molecular system formed should be considered as moderate polar processes. In BET analysis of the bonding changed along the analyzed key stages of the polymerization reaction between nitroethene and (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone, we can distinguish eleven topologically different phases. While the first step of these polymerizations is associated with the rupture of the C4–C5 double bond in nitroethene (1a) molecule and formation of C5 pseudoradical center, the second step is associated with the formation of O1–C4 single and N2–C3 double bonds. The next steps are associated with breaking the C6–C7 double bond in the second molecule of 1a, formation of C5–C6 single bond and C7 pseudoradical center. In the case of the second polymerization reaction studied between nitroethene (1a) and methyl vinyl ether (3), we can highlight nine different phases. The first stage includes breaking the C3–C4 and C1–C2 double bonds, respectively, and formation of C1–C3 single bond and C4 pseudoradical center. In the next group, we notice processes related to the attachment of a second nitroethene (1a) molecule, in particular rupture of the C5–C6 double bond, formation of C4–C5 single bond and C6 pseudoradical center.

References

Agrawal JP, Hodgson RD (2007) Organic Chemistry of Explosives. Wiley & Sons, Chichester

Perekalin VV, Lipina ES, Berestovitskaya VM, Efremov DA (1994) Nitroalkenes: Conjugated Nitro Compounds. Wiley & Sons, Chichester

Sheremet EA, Tomanov RI, Trukhin EV, Berestovitskaya VM (2004) Synthesis of 4-Aryl-5-nitro-1,2,3-triazoles. Russ J Org Chem 40:594–595

Łapczuk-Krygier A, Ponikiewski Ł, Jasiński R (2014) The crystal structure of (1RS,4RS,5RS,6SR)-5-cyano-5-nitro-6-phenyl-bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-ene. Crystal Reports 59:961–963

Żmigrodzka M, Dresler E, Hordyjewicz-Baran Z, Kulesza R, Jasiński R (2017) A unique example of non-catalyzed [3 + 2] cycloaddition involving (2E)-3-aryl-2-nitroprop-2-enenitriles. Chem Heterocycl Compd 53:1161–1162

Wadel PA, Pipic A, Zeller M, Tsetsakos P (2013) Sequential Diels–Alder/[3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement reactions of β-nitrostyrene with 3-methyl-1,3-pentadiene. Beilstein J Org Chem 9:2137–3146

Martıinez AR, Iglesias GYM (1998) Regio- and stereo-chemical study of the diels-alder reaction between (E)-3,4-Dimethoxy-β-nitrostyrene and 1-(Trimethylsilyloxy)buta-1,3-diene. J Chem Res (S) 4:169–169

Domingo LR, Ríos-Gutiérrez M, Pérez P (2016) A new model for C-C bond formation processes derived from the Molecular Electron Density Theory in the study of the mechanism of [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions of carbenoid nitrile ylides with electron-deficient ethylenes. Tetrahedron 72:1524–1532

Banerji A, Gupta M, Biswas PK, Prangé T, Neuman A (2007) 1,3-Dipolar cycloadditions. Part XII—Selective cycloaddition route to 4-nitroisoxazolidine ring systems. J Heterocycl Chem 44:1045–1049

Sridharan V, Muthusubramanian S, Sivasubramanian S, Polborn K (2004) Diastereoselective synthesis of 2,3,4,5-tetrasubstituted isoxazolidines via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Tetrahedron 60:8881–8892

Rembarz G, Kirchhoff B, Dongowski G (1966) Über die Reaktion von Phenylazid mit ω-Nitrostyrolen. J Prakt Chem 33:199–205

Jasiński R, Jasińska E, Dresler E (2017) A DFT computational study of the molecular mechanism of [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions between nitroethene and benzonitrile N-oxides. J Mol Model 23:13–21

Łapczuk-Krygier A, Jaśkowska J, Jasiński R (2018) The influence of Lewis acid catalyst on the kinetic and molecular mechanism of nitrous acid extrusion from 3-phenyl-5-nitro-2-isoxazoline: DFT computational study. Chem Heterocycl Compd 52:1172–1174

Woliński P, Kącka-Zych A (2018) Chemistry of 2-aryl-1-cyano-1-nitroethenes. Part II. Chemical transformations. Techn Transact 2:121–137

Buckley GD, Scaife CW (1947) Aliphatic nitro-compounds. Part I. Preparation of nitro-olefins by dehydration of 2-nitro-alcohols. J Chem Soc 1471–1472

Blomquist AT, Tapp WJ, Johnson JR (1945) Polymerization of nitroölefins. The preparation of 2-Nitropropene polymer and of derived vinylamine polymers. J Am Chem Soc 67:1519–1524

Eremenko LT, Gafurov RG, Lisina LA (1969) Synthesis of 3-fluoro-3, 3-dinitro-1-propanol and some of its esters. Bull Acad Sci USSR div 21:695–697

Jasiński R, Dresler E, Mikulska M, Polewski D (2016) [3 + 2] Cycloadditions of 1-halo-1-nitroethenes with (Z)-C-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-nitrone as regio- and stereocontrolled source of novel bioactive compounds: preliminary studies. Current Chem Lett 5:123–128

Wilkendorf R, Trénel M (1924) Zur Kenntnis aliphatischer Nitro-alkohole (II). Chem Ber 57:306–309

Sopova AS, Perekalin VV, Lebedeva WM, Yurchenko OI (1964) Zh Obshch Khim 34:1185–1187

Huisgen R, Penelle J, Mloston G, Buyle-Padias A, Hall HK Jr (1992) Can polymerization trap intermediates in 1, 3-dipolar cycloadditions? J Am Chem Soc 114:266–274

Jasiński R (2015) In the searching for zwitterionic intermediates on reaction paths of [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions between 2,2,4,4-tetramethyl-3-thiocyclobutanone S-methylide and polymerizable olefins. RSC Adv 5:101045–101048

Jasiński R (2009) Regio- and stereoselectivity of [2 + 3]cycloaddition of nitroethene to (Z)-N-aryl-C-phenylnitrones. Collect Czech Chem Commun 74:1341–1349

Jasiński R (2009) The question of the regiodirection of the [2 + 3] cycloaddition reaction of triphenylnitrone to nitroethene. Chem Heterocycl Compd 45:748–749

Jasiński R, Mróz K, Kącka A (2016) Experimental and theoretical DFT study on synthesis of sterically crowded 2,3,3, (4)5-Tetrasubstituted-4-nitroisoxazolidines via 1,3-Dipolar cycloaddition reactions between ketonitrones and conjugated nitroalkenes. J Heterocycl Chem 53:1424–1429

Jasiński R (2014) Searching for zwitterionic intermediates in Hetero Diels-Alder reactions between methyl α, p-dinitrocinnamate and vinyl-alkyl ethers. Comput Theor Chem 1046:93–98

Jasiński R (2018) β-Trifluoromethylated nitroethenes in Diels-Alder reaction with cyclopentadiene: a DFT computational study. J Fluor Chem 206:1–7

Jasiński A (2016) A reexamination of the molecular mechanism of the Diels-Alder reaction between tetrafluoroethene and cyclopentadiene. React Kinet Mech Cat 119:49–57

Zhao Y, Truhlar DG (2008) The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor Chem Account 120:215–241

Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Peralta JrJE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken B, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ (2009) Gaussian 09. Revision D.01. Gaussian. Inc. Wallingford CT

Scalmani G, Frisch MJ (2010) Continuous surface charge polarizable continuum models of solvation. I. General formalism. J Chem Phys 132:114110–114125

Silvi B, Savin A (1994) Classification of chemical bonds based on topological analysis of electron localization functions. Nature 371:683–686

Savin A, Silvi B, Colonna F (1996) Topological analysis of the electron localization function applied to delocalized bonds. Can J Chem 74:1088–1096

Becke AD, Edgecombe KE (1990) A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J Chem Phys 92:5397–5404

Noury S, Krokidis K, Fuster F, Silvi B (1999) Computational tools for the electron localization function topological analysis. Comput Chem 23:597–604

Krokidis X, Noury S, Silvi B (1997) Characterization of elementary chemical processes by catastrophe theory. J Phys Chem A 101:7277–7282

Thom R (1976) Structural stability and morphogenesis: an outline of a general theory of models. Inc., Reading, Mass

Woodcock AER, Poston T (1974) A geometrical study of elementary catastrophes. Spinger-Verlag, Berlin

Gilmore R (1981) Catastrophe theory for scientists and engineers. Dover, New York

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by PL-Grid Infrastructure in the regional computer center ‘Cyfronet’ in Cracow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Dedicated to Professor Grzegorz Mlostoń on the occasion of his 70th birthday.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kącka-Zych, A., Jasiński, R. A DFT study on the molecular mechanism of the conjugated nitroalkenes polymerization process initiated by selected unsaturated nucleophiles. Theor Chem Acc 139, 119 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-020-02627-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-020-02627-7