Abstract

Summary

Interventions targeting patients with recent fragility fracture and their physician were most successful at initiating osteoporosis treatment during the first 12 months. This window of opportunity had already closed after 1 year. The reasons for declining or accepting the intensive intervention were explored in patients still untreated at 12 months.

Introduction

A fragility fracture (FF) event identifies patients most likely to benefit from osteoporosis treatment. Nonetheless, most FF patients go untreated. Our objective was to determine how long an incident FF remains a strong incentive to initiate osteoporosis treatment.

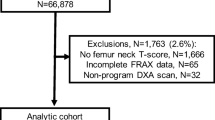

Methods

A total of 1086 men and women over age 50 with a recent FF event were assigned to either standard care (SC), to minimal (MIN), or intensive (INT) interventions targeting patients and their family physician to initiate osteoporosis treatment. Inpatients with FF (mainly hip) evaluated by rheumatologists were also included in a specialized group (SPE; n = 324). At 1 year, untreated patients in both the SC and the MIN groups were offered an INT intervention. The cohort was followed through 48 months. A qualitative analysis of patient-centered decision-making associated with initiation of treatment was conducted.

Results

In MIN and INT groups, osteoporosis treatment was initiated in 41.0 and 54.3% of untreated patients by 12 months, respectively, compared to 68.4% in SPE and 18.9% in SC groups; initiation rates drastically dropped thereafter. Over 4863 patient-years of follow-up, the rates of new FF were 3.4 per 100 patient-years, without significant differences between patients with initial major or minor FF, nor between control or intervention groups. Failure by patients and physicians to recognize FF as a sign of underlying bone disease contributed the most to lack of treatment.

Conclusion

While incident FFs are an ideal opportunity for starting osteoporosis treatment, 1 year later, the therapeutic window of opportunity has already closed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dennison E, Mohamed MA, Cooper C (2006) Epidemiology of osteoporosis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 32(4):617–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2006.08.003

Bessette L, Ste-Marie LG, Jean S, Davison KS, Beaulieu M, Baranci M, Bessant J, Brown JP (2008) The care gap in diagnosis and treatment of women with a fragility fracture. Osteoporos Int 19(1):79–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0426-9

Giangregorio L, Papaioannou A, Cranney A, Zytaruk N, Adachi JD (2006) Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap: an international phenomenon. Semin Arthritis Rheum 35:293–305

Leslie WD, Giangregorio LM, Yogendran M, Azimaee M, Morin S, Metge C, Caetano P, Lix LM (2012) A population-based analysis of the post-fracture care gap 1996-2008: the situation is not improving. Osteoporos Int 23(5):1623–1629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1630-1

Akesson K, Marsh D, Mitchell PJ, McLellan AR, Stenmark J, Pierroz DD, Kyer C, Cooper C (2013) Capture the fracture: a best practice framework and global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 24(8):2135–2152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2348-z

Bliuc D, Ong CR, Eisman JA, Center JR (2005) Barriers to effective management of osteoporosis in moderate and minimal trauma fractures: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int 16(8):977–982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-004-1788-x

Semerano L, Guillot X, Rossini M, Avice E, Begue T, Wargon M, Boissier MC, Saidenberg-Kermanac'h N (2011) What predicts initiation of osteoporosis treatment after fractures: education organisation or patients' characteristics? Clin Exp Rheumatol 29(1):89–92

Brown JP, Morin S, Leslie W et al (2014) Bisphosphonates for treatment of osteoporosis: expected benefits, potential harms, and drug holidays. Can Fam Physician 60:324–333

McClung M, Harris ST, Miller PD, Bauer DC, Davison KS, Dian L, Hanley DA, Kendler DL, Yuen CK, Lewiecki EM (2013) Bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis: benefits, risks, and drug holiday. Am J Med 126(1):13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.023

Dore N, Kennedy C, Fisher P, Dolovich L, Farrauto L, Papaioannou A (2013) Improving care after hip fracture: the fracture? Think osteoporosis (FTOP) program. BMC Geriatr 13(1):130. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-130

Black DM, Rosen CJ (2016) Clinical Practice. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 374(3):254–262. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1513724

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C et al (2004) A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone 35:375–382

Wustrack R, Seeman E, Bucci-Rechtweg C, Burch S, Palermo L, Black DM (2012) Predictors of new and severe vertebral fractures: results from the HORIZON pivotal fracture trial. Osteoporos Int 23(1):53–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1664-4

Warriner AH, Patkar NM, Yun H, Delzell E (2011) Minor, major, low-trauma, and high-trauma fractures: what are the subsequent fracture risks and how do they vary? Curr Osteoporos Rep 9(3):122–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-011-0064-1

Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR (2009) Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA 301(5):513–521. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.50

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17(12):1726–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4

Gehlbach S, Saag KG, Adachi JD, Hooven FH, Flahive J, Boonen S, Chapurlat RD, Compston JE, Cooper C, Díez-Perez A, Greenspan SL, LaCroix AZ, Netelenbos JC, Pfeilschifter J, Rossini M, Roux C, Sambrook PN, Silverman S, Siris ES, Watts NB, Lindsay R (2012) Previous fractures at multiple sites increase the risk for subsequent fractures: the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. J Bone Miner Res 27(3):645–653. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.1476

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, De Laet C, Jonsson B (2004) Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 15(3):175–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-003-1514-0

Curtis JR, Kim Y, Bryant T, Allison J, Scott D, Saag KG (2006) Osteoporosis in the home health care setting: a window of opportunity? Arthritis Rheum 55(6):971–975. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22349

Smith MD, Ross W, Ahern MJ (2001) Missing a therapeutic window of opportunity: an audit of patients attending a tertiary teaching hospital with potentially osteoporotic hip and wrist fractures. J Rheumatol 28:2504–2508

Compston JE, Seeman E (2006) Compliance with osteoporosis therapy is the weakest link. Lancet 368(9540):973–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69394-X

Roux S, Beaulieu M, Beaulieu MC, Cabana F, Boire G (2013) Priming primary care physicians to treat osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: an integrated multidisciplinary approach. J Rheumatol 40:703–711

Roux S, Cabana F, Carrier N, Beaulieu M, April PM, Beaulieu MC, Boire G (2014) The World Health Organization fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX) underestimates incident and recurrent fractures in consecutive patients with fragility fractures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99(7):2400–2408. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-4507

Kreiger N, Tenenhouse A, Joseph L, Mackenzie T, Poliquin S, Brown J, Prior J, Rittmaster R (1999) The Canadian multicentre osteoroposis study (CaMos): background, rationale, methods. Can J Aging 18(03):376–387. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980800009934

Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S, Hanley DA, Hodsman A, Jamal SA, Kaiser SM, Kvern B, Siminoski K, Leslie WD, for the Scientific Advisory Council of Osteoporosis Canada (2010) 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ 182(17):1864–1873. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.100771

Agresti A, Coull B (1998) Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am Stat 52:119–126

Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD, Forrester JE (2003) Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol 157(4):364–375. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf215

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Miles MB, Huberman AM (2003) Analyse des données qualitatives, 2e éd. edn. De Boeck Université, Paris

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, Wong PK (2008) Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 11(1):44–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x

Beaton DE, Sujic R, McIlroy Beaton K, Sale J, Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER (2012) Patient perceptions of the path to osteoporosis care following a fragility fracture. Qual Health Res 22(12):1647–1658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312457467

Schousboe JT (2013) Adherence with medications used to treat osteoporosis: behavioral insights. Curr Osteoporos Rep 11(1):21–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-013-0133-8

Sale JE, Gignac MA, Hawker G, Frankel L, Beaton D, Bogoch E, Elliot-Gibson V (2011) Decision to take osteoporosis medication in patients who have had a fracture and are 'high' risk for future fracture: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12(1):92. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-92

Weycker D, Macarios D, Edelsberg J, Oster G (2006) Compliance with drug therapy for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 17(11):1645–1652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0179-x

Boudou L, Gerbay B, Chopin F, Ollagnier E, Collet P, Thomas T (2011) Management of osteoporosis in fracture liaison service associated with long-term adherence to treatment. Osteoporos Int 22(7):2099–2106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1638-6

Clowes JA, Peel NF, Eastell R (2004) The impact of monitoring on adherence and persistence with antiresorptive treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(3):1117–1123. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2003-030501

Briot K, Cortet B, Thomas T et al (2012) 2012 update of French guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Joint Bone Spine 79:304–313

Leslie WD, Schousboe JT (2011) A review of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment options in new and recently updated guidelines on case finding around the world. Curr Osteoporos Rep 9(3):129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-011-0060-5

Compston J, Bowring C, Cooper A, Cooper C, Davies C, Francis R, Kanis JA, Marsh D, McCloskey EV, Reid DM, Selby P, National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (2013) Diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and older men in the UK: National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) update 2013. Maturitas 75(4):392–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.05.013

Inderjeeth CA, Chan K, Kwan K, Lai M (2012) Time to onset of efficacy in fracture reduction with current anti-osteoporosis treatments. J Bone Miner Metab 30(5):493–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-012-0349-1

Roux C, Briot K (2017) Imminent fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 28(6):1765–1769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-3976-5

Bischoff-Ferrari HA (2011) The role of falls in fracture prediction. Curr Osteoporos Rep 9(3):116–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-011-0059-y

Bonafede M, Shi N, Barron R, Li X, Crittenden DB, Chandler D (2016) Predicting imminent risk for fracture in patients aged 50 or older with osteoporosis using US claims data. Arch Osteoporos 11(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-016-0280-5

Bonafede MM, Shi N, Bower AG, Barron RL, Grauer A, Chandler DB (2015) Teriparatide treatment patterns in osteoporosis and subsequent fracture events: a US claims analysis. Osteoporos Int 26(3):1203–1212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2971-3

Melton LJ 3rd, Atkinson EJ, Cooper C, O'Fallon WM, Riggs BL (1999) Vertebral fractures predict subsequent fractures. Osteoporos Int 10(3):214–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980050218

Acknowledgements

We are especially indebted to our study coordinator Noémie Poirier for her continuing involvement and dedication.

Funding

Supported by unrestricted research grants from Merck Canada, Amgen Canada, The Alliance for Better Bone Health (Procter&Gamble, sanofi-aventis), Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc., Warner Chilcott Canada, Eli Lilly Canada and Servier Canada, and by the Centre de Recherche Clinique Étienne-LeBel (CRC) from the CHUS, which received a team grant from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQ-S). None of the funding sources had any role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data or in the decision to publish this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The Ethics Review Board of the CHUS approved the study (Clinical Trials.gov ID: NCT00512499).

ᅟ

Conflict of interest

No disclosure except GB who has received lecture fees or advisory board fees from BMS Canada, Celgene Canada, Novartis Canada, and UCB Canada; GB and SR from Eli Lilly Canada, Amgen Canada, and Pfizer Canada; IG has received research funding from Merck Canada, and SR from BMS and Pfizer Canada.

Ethical approval

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the CHUS institutional research committee and with TCPS 2 (2014)- the latest edition of Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roux, S., Gaboury, I., Gionet-Landry, N. et al. Using a sequential explanatory mixed method to evaluate the therapeutic window of opportunity for initiating osteoporosis treatment following fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int 29, 961–971 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4374-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4374-8