Abstract

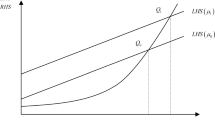

We introduce non-homothetic preferences into an R&D based growth model to study how demand forces shape the impact of inequality on innovation and growth. Inequality affects the incentive to innovate via a price effect and a market size effect. When innovators have a large productivity advantage over traditional producers a higher extent of inequality tends to increase innovators’ prices and mark-ups. When this productivity gap is small, however, a redistribution from the rich to the poor increases market sizes and speeds up growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Non-homothetic preferences have turned out important to explain the structural changes in employment and output in long-run growth, see Matsuyama (1992, 2008), Buera and Kaboski (2006), Foellmi and Zweimüller (2008), and Boppart (2014). Other papers have studied how inequality affects growth via non-homotheticities have also emphasized market size effects. In Matsuyama (2002) technical progress is driven by learning by doing and an intermediate degree of inequality is required to realize the full learning potential. Falkinger (1994) studies the impact on inequality on market sizes under the assumption of exogenously given profit-margins. In Chou and Talmain (1996) consumers have non-homothetic preferences over a homogenous consumption good and a (CES) bundle of differentiated goods which affects the market size (but not the mark-up) of innovators. Zweimüller (2000) provides a dynamic version of Murphy et al. (1989). In Galor and Moav (2004) non-homotheticities affect growth via savings rates that differ by income. A very different strand of the literature studies the interrelationship between consumption/savings, inequality and growth in the Post-Keynesian tradition. For recent contributions, see Salvadori (2006) and Kurz and Salvadori (2010).

The assumption that labor and capital endowments are perfectly correlated and identically distributed is made for analytical convenience. Below we assume additive and logarithmic intertemporal preferences generating equal optimal savings rates for all households. This assumption (and the absence of income shocks) ensures that the initial distribution of θ persists over time. Hence time indices for θ are omitted.

The log intertemporal utility is used for ease of exposition. The same results would hold true (in particular the invariance of distribution) if the utility would be CRRA in the consumption aggregator \(\int _{0}^{\infty }x(\theta ,j,t)dj\).

An isomorphic case would the situation where innovative firms produce a better product, yielding higher utility, with the same production technology as traditional firms (or some combination of productivity/quality gain).

With K groups of consumers, there are K firm types such that type 1 sells to the richest group (and charges their willingness to pay), the second type sells to the richest and second richest (and charges the willingness to pay of the second richtest group), ...., and the K t h type sells to all households (charging the willingness to pay of the poorest group). In equilibrium the distribution of firms across types is endogenous and satisfies conditions (i) and (ii) mentioned in text.

Instead of writing consumption expenditures of a household with endowment \(\tilde {\theta }\) as \(\int _{0}^{N(\tilde {\theta })}p(j)dj\) we can write \(\int _{\underline {\theta }}^{\tilde {\theta }} p(\theta )dN(\theta )+ p(\underline {\theta } )N(\underline {\theta })\) where \(N(\underline {\theta })\) and \(p(\underline { \theta })\) are the menu and the price of the goods that the poorest household can afford.

In a model with representative agents, we analysed the extensive margin to study demand-driven structural change (Foellmi and Zweimüller 2008).

The reference to “risk” is misleading here since risk and uncertainty do not play a role in our analysis. CRRA features a constant elasticity of marginal utility with respect to the level of consumption. In the present context, decreasing relative risk aversion (DRRA) means that the elasticity of marginal utility is increasing with consumption, implying that rich households save a larger fraction of their income that the poor.

References

Alesina A, Rodrik D (1994) Distributive politics and economic growth. Q J Econ 109:465–490

Araujo RA (2013) Cumulative causation in a structural economic dynamic approach to economic growth and uneven development. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 24:130–140

Argyrous G (1996) Cumulative causation and industrial evolution: Kaldor’s four stages of industrialization as an evolutionary model. Journal of Economic Issues 30:97–119

Atkinson AB (2015) Inequality, What Can Be Done. Harvard University Press

Banerjee AV, Duflo E (2003) Inequality and growth: what can the data say? J Econ Growth 8:267– 299

Barro RJ (2000) Inequality and growth in a panel of countries. J Econ Growth 5:5–32

Barro RJ (2008) Inequality and Growth Revisited, Working Papers on Regional Economic Integration 11, Asian Development Bank

Berg A, Ostry J (2011) Inequality and unsustainable growth. International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C.

Berger S, Elsner W (2007) European contributions to evolutionary institutional economics: the cases of ‘cumulative circular causation’ (CCC) and ‘open systems approach’ (OSA). Some methodological and policy implications. Journal of Economic Issues 41:529–537

Bernardino J, Araujo T (2013) On positional consumption and technological innovation: an agent-based model. J Evol Econ 23:1047–1071

Boppart T (2014) Structural change and the kaldor facts in a growth model with relative price effects and non-Gorman preferences. Econometrica 82:2167–2196

Boushey H, Price CC (2014) How are economic inequality and growth connected? A review of recent research. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, Washington D.C

Bertola G, Foellmi R, Zweimüller J (2006) Income distribution in macroeconomic models. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Buera FJ, Kaboski JP (2006) The rise of the service economy. Working Paper, Northwestern and Ohio State Universities

Chai A, Rohde N (2012) Addendum to Engel’s Law: the dispersion of household spending and the influence of relative income. Mimeo, Griffith University

Chou C-F, Talmain G (1996) Redistribution and growth: Pareto improvements. J Econ Growth 1:505– 523

Ciarli T, Lorentz A, Savona M, Valente M (2010) The effect of consumption and production structure on growth and distribution. A micro to macro model. Metroeconomica 61:180–218

Deininger K, Squire L (1996) A new data set measuring income inequality. World Bank Econ Rev 10:565–591

Falkinger J (1994) An engelian model of growth and innovation with hierarchic demand and unequal incomes. Ric Econ 48:123–139

Falkinger J, Zweimüller J (1996) The cross-country Engel curve for product diversification. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 7:79–97

Foellmi R, Zweimüller J (2006) Income distribution and demand-induced innovations. Rev Econ Stud 73:941–960

Foellmi R, Zweimüller J (2008) Structural change, engel’s consumption cycles, and Kaldor’s facts of economic growth. J Monet Econ 55:1317–1328

Foellmi R, Wuergler T, Zweimüller J (2014) The macroeconomics of model T. J Econ Theory 153:617–647

Forbes KJ (2000) A reassessment of the relationship between inequality and growth. Am Econ Rev 90:869–887

Galor O, Moav O (2004) From physical to human capital accumulation: inequality and the process of development. Rev Econ Stud 71:1001–1026

Halter D, Oechslin M, Zweimüller J (2014) Inequality and growth: The neglected time dimension. J Econ Growth 19:81–104

Hayek FA (1953) The case against progressive income taxes. The Freeman:229–232

Jackson LF (1984) Hierarchic demand and the engel curve for variety. Rev Econ Stat 66:8–15

Kaldor N (1966) Causes of the slow rate of economic growth of the United Kingdom. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kaldor N (1981) The role of increasing returns, technical progress and cumulative causation in the theory of international trade. Economie Appliquée 34:593–617

Kurz HD, Salvadori N (2010) The post-Keynesian theories of growth and distribution: a survey. Handbook of Alternative Theories of Economic Growth:95

Kuznets S (1955) Economic growth and income inequality. Am Econ Rev 45:1–28

Lorentz A, Ciarli T, Savona M, Valente M (2015) The effect of demand-driven structural transformations on growth and technological change. J Evol Econ. forthcoming

Matsuyama K (1992) Agricultural productivity, comparative advantage, and economic growth. J Econ Theory 58:317–334

Matsuyama K (2002) The rise of mass consumption societies. J Polit Econ 110:1035–1070

Matsuyama K (2008) Structural change in an interdependent world: a global view of manufacturing decline. J Eur Econ Assoc 7:478–486

Murphy KM, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1989) Income distribution, market size, and industrialization. Q J Econ 104:537–564

Ostry JD, Berg A, Tsangarides CG (2014) Redistribution, inequality and growth. Discussion Note, IMF Staff Discussion Paper

Persson T, Tabellini G (1994) Is inequality harmful for growth? Am Econ Rev 84:600–621

Piketty T (2014) Capital in the 21st Century. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Salvadori N (2006) Economic growth and distribution: on the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Edward Elgar Publishing

Saviotti PP (2001) Variety, growth and demand. J Evol Econ 11:119–142

Schmookler J (1966) Inventions and economic growth. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Voitchovsky S (2005) Does the profile of income inequality matter for economic growth?. J Econ Growth 10:273–296

Voitchovsky S (2009) Inequality, growth and sectoral change. In: Salverda W, Nolan B, Smeeding TM (eds) Oxford handbook of economic inequality. Oxford Handbooks in Economics

Witt U (2001) Learning to consume - a theory of wants and the growth of demand. J Evol Econ 11:23–36

Young AA (1928) Increasing returns and economic progress. Econ J 38:527–542

Zweimüller J (2000) Schumpeterian entrepreneurs meet engel’s law: the impact of inequality on innovation-driven growth. J Econ Growth 5:185–206

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Sinergia Grant #CRSII1-154446).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Josef Zweimüller is also associated with CESifo and IZA.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof of Lemma 1

Proof

-

a.

Differentiating z(θ, t) with respect to t, using \(\dot {N}(\theta ,t)/N(\theta ,t)=g, \) yields \(\dot {z}(\theta ,t)/z(\theta ,t)=r-\rho -g\). Guess that g = r−ρ, so z(θ) is stationary. In that case household θ purchases all goods with prices lower than or equal p(θ) at all times and pays average price \(\bar {p}(\theta ), \)constant over time, and has expenditures \(\bar {p}(\theta )N(\theta ,t)\). Notice further that wages evolve according to \(w(t)=bN(\tau )e^{-\left (r-g\right ) (t-\tau )}\) and that V(τ) = b F N(τ) (since the value of each firm is π/r = b F). This allows us to rewrite the household’s lifetime budget constraint as \(\bar {p}(\theta )N(\theta ,t)=N(t)\theta b(1+\rho F/L)\), confirming our guess that N(θ, t) and N(t) grow pari passu.

-

b.

The budget constraint of the poorest consumer is \(p(\underline {\theta })N(\underline {\theta } ,t)=N(t)\underline {\theta } b(1+\rho F/L)\). We calculate \( p(\underline {\theta } )\) using \(p(\underline {\theta } )-b/a=\) \([1-G(\hat {\theta } )][1-b/a]\) (all firms make the same profit), (2) and r = g + ρ. This yields \(p(\underline {\theta } )=(g+\rho )bF/L+b/a\). Substituting into the budget constraint and solving for N(θ, t) yields the first claim of part b). The budget constraint of household \(\theta \in (\underline {\theta } ,\hat {\theta })\) is \(p(\underline {\theta } )N(\underline {\theta },t)+\int _{\underline {\theta } }^{\theta } p(\xi )dN(\xi ,t)=N(t)\theta b(1+\rho F/L)\). Differentiating with respect to θ yields \(p(\theta )\left [ dN(\theta ,t)/d\theta \right ] =N(t)b(1+\rho F/L)\). Solving for d N(θ, t)/d θ and integrating yields \(N(t)b(1+\rho F/L)\int _{\underline {\theta } }^{\theta } (1/p(\xi ))d\xi +N(\underline {\theta } ,t)\). Calculating \(p(\xi )=b\left [ (g+\rho )aF+(1-G(\xi ))L\right ] /\left [ a(1-G(\xi ))L\right ] \) from Eq. 2 and substituting into the previous equation yields the second claim of part b). By definition, household \(\hat {\theta }\) purchases all goods produced by monopolistic firms but no goods produced by the competitive fringe. A household \(\theta >\hat {\theta }\) spends \(N(t)\hat {\theta }b(1+\rho F/L)\) for the N(t) monopolistic goods and \(N(t)(\theta -\hat {\theta })b(1+\rho F/L)\) for the remaining N(θ, t)−N(t) goods produced by the competitive fringe. This yields the third claim of part b).

□

1.2 Proof of Proposition 1

Proof

-

a.

The integrand in Eq. 4 is a concave function of G(∙). If G(∙) undergoes a second order stochastically dominated transfer, where \(\int _{0}^{\hat {\theta }}G(\theta )d\theta \) remains unchanged, the value of the integral in Eq. 4 must increase due to Jensen’s inequality. Hence, the consumption curve (4) shifts up at \(\theta =\hat {\theta }\). Further, with \(G(\hat { \theta })\) unchanged, the zero profit constraint does not change at \(\theta = \hat {\theta }\), therefore the equilibrium growth rate rises.

-

b.

The integrand in Eq. 4 takes lower values at the values of θ involved in the transfer. Hence the value of the integral in Eq. 4 decreases meaning that less purchasing power is left in the hands of households with \(\theta <\hat {\theta }\). Around \(\theta =\hat { \theta }, \)the consumption curve shifts down and the zero profit constraint remains unaffected, the growth rate decreases. c. Neither (2) nor (4) are affected for \(\theta \leq \hat {\theta }\).

□

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Foellmi, R., Zweimüller, J. Is inequality harmful for innovation and growth? Price versus market size effects. J Evol Econ 27, 359–378 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-016-0451-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-016-0451-y