Abstract

In this paper we explore how specific aspects of market transparency and agents’ behavior affect the efficiency of the market outcome. In particular, we are interested whether learning behavior with and without information about actions of other participants improves market efficiency. We consider a simple market for a homogeneous good populated by buyers and sellers. The valuations of the buyers and the costs of the sellers are given exogenously. Agents are involved in consecutive trading sessions, which are organized as a continuous double auction with order book. Using Individual Evolutionary Learning agents submit price bids and offers, trying to learn the most profitable strategy by looking at their realized and counterfactual or “foregone” payoffs. We find that learning outcomes heavily depend on information treatments. Under full information about actions of others, agents’ orders tend to be similar, while under limited information agents tend to submit their valuations/costs. This behavioral outcome results in higher price volatility for the latter treatment. We also find that learning improves allocative efficiency when compared to outcomes with Zero-Intelligent traders.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The question “What makes markets allocatively efficient?” has attracted a lot of attention in recent years. Laboratory experiments with human subjects starting with Smith (1962) show quick convergence towards competitive equilibrium, also resulting in high allocative efficiency of the continuous double auction (CDA). A natural question arises about the significance of rationality for this outcome. With the assumption of forward-looking, strategic, optimizing agents, whose beliefs about others’ preferences and behavior are updated in a Bayesian way, the standard economic approach suggests solving for a rational expectations equilibrium under specified market rules. For some examples in this spirit see Easley and Ledyard (1993), Friedman (1991) and Foucault et al. (2005). In our opinion, the fully rational approach is not completely satisfactory for two reasons. First, the rational expectation approach embeds considerable model simplifications. Rather restrictive assumptions are often imposed either on information or on strategy space or on traders’ preferences. Given the complexity of the CDA market and the high dimension of the strategy space, a full solution is not feasible. Second, and more importantly, the behavioral and experimental literature shows that people fail to optimize, to learn in a Bayesian way, and to behave strategically in a sophisticated manner. In other words, people are only boundedly rational. Recent research suggests that models with boundedly rational learning behavior fit observed outcomes better (see, for example, Duffy (2006) for a survey).

To provide an extreme example of bounded rationality, Gode and Sunder (1993) introduced Zero Intelligent (ZI) agents. ZI traders do not have memory and do not behave strategically, submitting random orders subject to budget constraints. The ZI methodology has led to the impression that the rules of the market and not individual rationality are responsible for market’s allocative efficiency. In fact, Gode and Sunder (1993) find that market organized as a continuous double auction (CDA) is highly efficient and in some cases allows ZI traders to extract around 99% of possible surplus. More careful investigation in Gode and Sunder (1997) reveals, however, that specific market rules may significantly affect efficiency in the presence of the ZI agents. LiCalzi and Pellizzari (2008) have shown that the allocative efficiency of the CDA would drop substantially if every transaction did not force agents to submit new orders. Nevertheless, as pointed out in the recent reviews by Duffy (2006) and Ladley (2012), the ZI methodology is useful in studying market design questions, because any effect of design on efficiency under ZI behavior should be attributed solely to the change of market rules.

This paper focuses on a market design question, the question of market transparency. In January 2002 the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) introduced OpenBook system which effectively opened the content of the limit order book to public. Boehmer et al. (2005) show that this increasing transparency affected investors’ trading strategies and resulted in decreased price volatility and increased liquidity. Can these changes be explained by a theoretical model? This question cannot be studied within the ZI methodology, since the agents do not condition on any market information and their behavior is exactly the same under full information and limited information. For this reason we follow an intermediate approach between zero intelligence and full rationality. More precisely, we analyze allocative efficiency in the market with boundedly rational agents. While their valuations and costs are not changing from one trading session to another, the agents’ bidding behavior does. We use the Individual Evolutionary Learning (IEL) algorithm, introduced in 2003 and published as Arifovic and Ledyard (2011). This algorithm builds on the framework introduced by Arifovic (1994) who examined genetic algorithms (GA) as a model of social as well as individual learning of economic agents in the context of the cobweb model.Footnote 1 According to the IEL algorithm agents select their strategies (limit order prices) not only on the basis of their actual performance, but also of their counterfactual performance. To take the informational aspect into account, we distinguish between two scenarios. We compare an outcome of learning based on the information available in the open order book and an outcome of learning based only on aggregate market information, i.e., when the order book is closed. Similar questions were recently analyzed in Arifovic and Ledyard (2007) for call auction market, while we address them here for the CDA market.

We analyze what kind of behavior emerges as an outcome of the learning process under both information scenarios. In relation to that, we look at whether and how individual learning affects the aggregate properties, such as allocative efficiency. First of all, we show that learning may result in a sizeable increase in efficiency with respect to the ZI behavior. Secondly, we find that the agents learn to behave differently depending on the information available. In the open order book treatment the agents participating in trade learn to submit bids and asks that fall within the range of equilibrium prices. On the other hand, in the closed book treatment the trading agents submit bid/ask prices which are close to their valuations/costs.Footnote 2 Consequently, usage of the book information decreases market volatility, which is consistent with empirical evidence. Thus, our results provide a behavioral explanation for some of the observed effects of a change in the market rules.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The market environment is explained in Section 2, where we also recall the definition of allocative efficiency and derive a benchmark for ZI traders. We describe the individual evolutionary learning model in Section 3. The resulting market outcomes are simulatedFootnote 3 and discussed in Section 4. In Section 5 we report the results of a number of robustness tests that we conducted. Section 6 concludes. For brevity the paper uses a number of acronyms. The detailed list of acronyms and the corresponding definitions are given in Appendix.

2 Model

We start with describing environment and defining competitive equilibrium as a benchmark against which the outcomes under different learning rules will be compared. We then proceed by explaining the continuous double auction mechanism. Finally, we study the allocative efficiency under ZI trading.

2.1 Environment

Suppose we have a fixed number B + S of market participants, B buyers and S sellers. At the beginning of a trading session t ∈ {1, ..., T}, each seller is endowed with one unit of commodity and each buyer would like to consume one unit of commodity. The same agents transact during T trading sessions. Throughout the paper index b ∈ {1,...,B} denotes a buyer and index s ∈ {1,...,S} denotes a seller.

We consider a situation in which the valuation of every buyer and the cost of every seller is fixed over time.Footnote 4 A buyer’s valuation of a good, V b , is the amount, which is received when a unit is bought. A seller’s cost, C s , is the amount, which is paid when a unit is sold. It is assumed that each trader knows his own valuation/cost, but neither the exact valuations and costs of others, nor the distribution of these values is available. The ability to relax the common knowledge assumption typical in a standard game theoretic framework is one of the features of the evolutionary learning approach used here. As this and many other papers demonstrate, even without common knowledge assumption, the learning behavior of agents can produce reasonable strategies and even converge to the equilibrium.

Traders care about payoff defined as their surplus obtained from trade, i.e.,

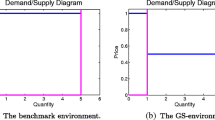

Given the set of valuations, \(\{V_b\}_{b=1}^B\), and costs, \(\{C_s\}_{s=1}^S\), one can build step-wise aggregate demand and supply curves, whose intersection determines the competitive equilibrium. This outcome will serve as a theoretical benchmark, as it maximizes the mutual benefits from trade. More specifically, the intersection of demand and supply determines a uniqueFootnote 5 equilibrium quantity q * ≥ 0 and, in general, an interval of the equilibrium prices \([p^*_L,p^*_H]\). This situation is illustrated in Fig. 1 for two different market environments. The units, which would yield a nonnegative payoff if traded at an equilibrium price, are called intramarginal (in the figure they are to the left of the equilibrium quantity). The agents who own these units are called intramarginal buyers (IMBs) and intramaginal sellers (IMSs). The units, which would yield a negative payoff if traded at an equilibrium price, are called extramarginal (in the figure they are to the right of the equilibrium quantity), The agents who own these units are extramarginal buyers and sellers (EMBs and EMSs). The sum of all payoffs of buyers and sellers gives the allocative value of a trading session. When all transactions occur at an equilibrium price, this value is maximized and is equal to the difference between the sum of the valuations of all IBMs and the sum of the costs of all IMSs. We adopt the following

Definition 2.1

The allocative efficiency of a trading session is the ratio between realized allocative value during the session and maximum possible allocative value.

In this paper we consider three market environments. We present the market introduced in Gode and Sunder (1997) (GS, henceforth) in Fig. 1a. There is one seller offering a unit which costs C 1 = 0, and N = 1 + n buyers who wish to consume one unit, one of which has valuation V 1 = 1 and others have the same valuations equal to 0 ≤ β ≤ 1. The equilibrium price range is given by (β, 1]. The seller and the first buyer are intramarginal. A transaction between them results in a competitive outcome with efficiency equal to 1. The n buyers with valuation β are EMBs and when the seller transacts with one of them the efficiency is β ≤ 1. This “GS-environment” may seem too stylized, but it is analytically tractable and provides good intuition. Moreover, by varying β, we can demonstrate that the allocative efficiency of the CDA depends on the environment.

While in the first environment the seller has a higher market power than the buyers, in the second environment this asymmetry is removed and the number of buyers and sellers is equal to N. For a given N the set of valuations is \(\left\{\tfrac{k}{N}\right\}\) and the set of costs is \(\left\{\tfrac{k-1}{N}\right\}\) with integer k ∈ [1, N]. Consequently the demand and supply schedules are symmetric and the equilibrium quantity is given by \(\left\lceil \tfrac{N}{2} \right\rceil\).Footnote 6 We call this symmetric environment with N buyers and N sellers “SN-environment”. When N is even, there exists a unique equilibrium price \(\tfrac{1}{2}\), and when N is odd, the equilibrium price range is given by \(\left(\tfrac{N-1}{2N},\tfrac{N+1}{2N}\right)\). Figure 1b shows the “S5-environment” which we study in this paper.

The last environment we consider is depicted in Fig. 1c. There are 5 buyers and 5 sellers in this market, 4 IMBs and 4 IMSs.Footnote 7 This example is similar to the previous environment for N = 5 but less symmetric. Furthermore, it is one of the configurations for which Arifovic and Ledyard (2007) study the effect of the transparency in the market organized as a call auction, so that a direct comparison with the CDA market can be made. We refer to this environment AL, henceforth.

2.2 Continuous double auction

In our model in every trading session the market is operating as the Continuous Double Auction (CDA) with an order book.Footnote 8 This is a market mechanism for a-synchronous trading, common to the stock exchanges nowadays. If a newly submitted order finds a “matching order,” it is satisfied at the price of this matching order. A matching order is defined as an order stored in the opposite side of the book at whose price the transaction with a newly arrived order is possible. If there are many orders which match the incoming order, the matching order with which the trade occurs is selected according to the price-time priority. If the submitted order does not find a matching order, it is stored in the book and deleted only at the end of the session when the book is cleared.

We assume that every agent submits only one order (bid or ask depending on the agent’s type) during a trading session.Footnote 9 The agents determine their orders before the session starts. Consequently, they cannot condition their order on the state of the book. The sequence of traders’ arrivals to the market is randomly permuted for every session. At the end of each trading session the order book is cleared by removing all the unsatisfied orders, so that the next session starts with an empty book.

For a given set of agents’ orders and their arrival sequence, the CDA mechanism described above generates a (possibly empty) sequence of transactions. The prices at which buyer b and seller s traded during trading session t are denoted by p b,t and p s,t , while their orders are given by b b,t and a s,t , respectively. In case b traded with s, price p b,t =p s,t is the price of this transaction. It is equal to b b,t if b arrived before s and to a s,t , otherwise. According to Eq. 2.1, buyer b who traded at price p b,t extracts payoff V b − p b,t , while the buyer who did not trade over the session gets 0. Similarly, seller s who succeeded in selling the unit at price p s,t receives payoff p s,t − C s , while the seller who did not trade gets 0. Note that in the CDA market the payoff a trader attains depends not only on submitted orders but also on the sequence of their trade.

2.3 Market efficiency with ZI-traders

What is the role of a market mechanism in determining market efficiency? A benchmark for efficiency of a market mechanism might be given by its performance when the traders are Zero Intelligent (ZI).Footnote 10 Every trading period ZI traders submit random orders, drawing them independently from a uniform distribution. Gode and Sunder (1993) distinguish between constrained and unconstrained ZI traders. Unconstrained ZI traders can draw orders from a whole interval [0, 1], while constrained traders are not allowed to bid higher than their valuation or ask lower than their cost. Gjerstad and Shachat (2007) attribute this restriction to individual rationality (IR) in the order submission, rather than to a market rule. We follow their terminology and distinguish between agents “with IR” and “without IR”. A buyer with IR will not submit an order higher than the valuation. A seller with IR will not submit an order lower than the cost.

2.3.1 GS-environment

We derive an analytic expression for the allocative efficiency of the CDA with ZI traders for the GS-environment depicted in Fig. 1a, when the number of extramarginal buyers n → ∞. Note that in our setup a trading session may result in no transaction, whereas Gode and Sunder (1997) guarantee transaction by introducing an unlimited number of trading rounds.

Proposition 2.1

Consider the CDA in the GS-environment when n → ∞. The expected allocative efficiency under ZI agents with IR converges to

the expected allocative efficiency under ZI agents without IR converges to

Proof

See Appendix. □

Consider first the IR case. The solid line in Fig. 2a shows the theoretical efficiency (Eq. 2.2) as a function of β. Its U-shape reflects a trade-off between the probability of inefficient transaction and the size of inefficiency. The probability of a transaction with an EMB increases in β, while the losses of allocative efficiency due to this transaction decrease in β. The probability of no trade decreases with β. Comparing Eq. 2.2 with Eq. 6 from Gode and Sunder (1997) reproduced below

we observe that efficiency in a market with one trading round is lower than in a market with unlimited number of trading rounds. In our setup efficiency can be lower than 1 not only due to a transaction with an extramarginal trader but also due to the absence of trade.

Figure 2a also shows the average allocative efficiency for a finite number n of EMBs. The average is computed over T = 100 trading sessions and S = 100 random seeds. We observe that the effect of finite number of agents is not very strong. As number of agents n increases the average efficiency over the simulation runs converges to the theoretical efficiency derived in Proposition 2.1. Figure 2b shows the efficiency without IR. EMB traders are no longer bounded by their valuation β and are now competing with a unique IMB who trades with probability of 1/(n + 1), which converges to 0 as n → ∞. As a result, no transaction outcome is ruled out and non-equilibrium transactions become the only source of inefficiency. The trade-off between the probability of an inefficient transaction and the size of the inefficiency (equal to β) disappears. It explains a linear shape of the efficiency curve. Comparison with the IR case reveals a surprising conclusion. For high values of β (namely for \(\beta>\sqrt{2}-1\)) the absence of the IR in order submission leads to higher efficiency.

2.3.2 S5- and AL-environments

Next we analyze outcomes under the ZI benchmark in the two other environments introduced in Section 2.1 and shown in Fig. 1b and c, respectively. An important difference with respect to the GS-environment is that now more than one transaction can occur during a single trading session, at different transaction prices. In this case, we report the average price for all transactions during a given session.

A well known result of Gode and Sunder (1993), obtained for similar environments, is that the allocative efficiency is close to 100%. It is obtained, however, under assumption that the multiple rounds of bidding are allowed and the book is cleared after every transaction. We want to verify this claim relaxing this assumption and allowing only one order per agent in any given trading session. We simulate the trading under ZI agents with and without IR for 100 trading sessions. Figure 3 shows dynamics of the (average) price, efficiency and number of transactions in the S5 (top panels) and AL (bottom panels) environments. On the price panel we show the equilibrium price range with two horizontal lines. We observe, first, that the average price over the trading session is volatile and is often outside of the equilibrium range. Second, when the IR is imposed, the sessions without transactions occur more frequently than in the case without IR. Third, absence of IR can also lead to overtrading, i.e., to a larger than equilibrium number of transactions.

Table 1 reports the average allocative efficiency, average price, and the average number of transactions over T = 100 trading sessions, as well as price volatility (standard deviation) over T periods. All these statistics are also averaged over S = 100 random seeds. In both environments the average allocative efficiency with ZI agents is far less than 100%, with a dubious effect of individual rationality. In the absence of IR, agents transact more often and the number of transactions is closer to the equilibrium level. On the other hand, many transactions lead to negative payoffs for individual traders. As a result in the S5-environment the efficiency is higher in the case with IR relative to the case without IR, when the efficiency turns negative in several sessions. An opposite result holds for the AL-environment, where the individual rationality constraints lower allocative efficiency.

To summarize, our simulations with ZI agents show that the allocative efficiency in the market does depend on the market environment (rather than only on the market rules) and is typically much lower than 100%. Further, imposing the IR constraints in agents’ order submissions does not necessarily improve allocative efficiency.

3 Individual evolutionary learning

Our result of low market efficiency under ZI implies that the individual rationality can have a positive effect on the efficiency and makes an analysis of the market with intelligent traders meaningful. Furthermore, as we already mentioned, the market design questions cannot be addressed within the ZI methodology, when random behavior is invariant to the change in design. In the rest of the paper we investigate market outcomes under a simple evolutionary mechanism of individual learning, which reinforces successful and discourages unsuccessful strategies.

In our setting, an observed action of every agent during a trading round is one submitted order. The evolution of the orders is modeled by the Individual Evolutionary Learning (IEL) algorithm which involves the following steps:

-

specification of a space of strategies (or messages);

-

limiting this space to a small pool of strategies for every trader;

-

choosing one message from the pool on the basis of its performance measure;

-

evolving the pool using experimentation and replication.

IEL is based on an individual (not social) evolutionary process. It is well suited for applications in environments with large strategy spaces (subsets of real line) such as our CDA environment. See Arifovic and Ledyard (2004) for a discussion of the advantages of IEL over other commonly used models of individual learning, such as reinforcement learning (Erev and Roth 1998) and Experience-Weighted Attraction learning (Camerer and Ho 1999), in the environments with large strategy spaces.

Messages

We assume that a message, ε b,t (ε s,t ), represents a potential bid (or ask) order price from buyer b (or seller s) at trading session t. In our base treatment we do not allow a violation of the IR constraints, that is, we require ε b,t ≤ V b and ε s,t ≥ C s . Under alternative treatments without IR constraints these restrictions will not be imposed and we will let traders themselves learn not to submit orders which lead to individual losses. In all specifications we assume that possible orders belong to the interval [0, 1].

Individual pool

Even if there is a continuum of possible messages, every agent will be restricted at every time to choose between a limited amount of them. The pool of messages (bids) available for submission at time t by buyer b is denoted by B b,t . The pool of messages (asks) available for submission at time t by seller s is denoted by A s,t . Every period the pool of each agent is updated, but the number of messages in the pool is fixed and equals to J. Some of the messages in the pool might be identical, so that an agent may be choosing from J or less possible alternatives. Initially, the individual pools contains J strategies drawn, independently for each agent, from the uniform distribution on the interval of admissible messages, i.e., [V b , 1] for buyers and [0, C s ] for sellers when the IR constraints cannot be violated and [0, 1] for all traders in the absence of IR. In the benchmark simulations J = 100 and the IR constraints are imposed.

The pool used at time t is updated before the following trading session by subsequent application of two procedures: experimentation (or mutation) and replication. During the experimentation stage, any message from the old pool can be replaced with a small probability by some new message. In such a way for every buyer and seller the intermediate pools are formed. More specifically, each message is removed from the pool with a small probability of experimentation, ρ, or remains in the old pool with probability 1 − ρ. In case that a message is removed, it is replaced by a new message drawn from a distribution, \(\mathcal{P}\). In the benchmark simulations ρ = 0.03 and distribution \(\mathcal{P}\) is uniform on the interval [V b , 1] for buyers and [0, C s ] for sellers.

At the replication stage two randomly chosen messages from the just-formed (intermediate) pool are compared with each other, and the best of them occupies a place in a new pool, B b,t + 1, for a buyer or A s,t + 1 for a seller. For every agent such a process is independently repeated J times (with replacement), in order to fill all the places in the new pool. The comparison is made according to a performance measure which is defined below. Therefore, during replication, we increase an amount of “successful” messages in the pool at the expense of less successful ones.

Calculating the foregone payoffs

How good is a given message? Indeed, only the message which has actually been used last period delivers a known payoff given by Eq. 2.1. An agent who is learning would also like to infer foregone payoffs from alternative strategies. To do this, every agent applies a counterfactual analysis. Notice that this is a boundedly rational reasoning, since our agent ignores the analogous learning process of all the other agents.

The calculation of foregone payoff is also made according to Eq. 2.1, but the price of transaction is notional and depends on the amount of information which is available to the agent. We distinguish between two treatments which we call open book (OP) and closed book (CL) information treatment. Under the OP treatment each agent uses the full information about all bids, offers and prices from the previous period. Only the identities of bidders are not known preventing direct access to the behavioral strategies used by others. Under the CL treatment the agents are informed only about some price aggregate, say average price, from the previous session, \(P^{\text{av}}_t\). If no transaction occurred during this session, \(P^{\text{av}}_t\) is set to an average price of the most recent past session for which at least one transaction had occurred. Note that the availability and use of the information from the book may be attributed either to market design, e.g., openness of the market or costs of the access to the book, or to individual behavior, e.g., willingness to buy information or possibility to process it, or both.

Let \(\mathcal{I}_t\) denote the largest possible information set after the trading session t. It includes the orders of all buyers and sellers as well as sequence in which they arrive at the market. Under the CL treatment this whole set is not known to traders: they know only their own bids and asks as well as an average price. Thus, under the CL treatment the information sets of buyers and sellers at the end of session t are given as

The order book of the past period cannot be reconstructed with this information. Hence, agent can only use average price of the previous session as an indication for possible realized price given alternative message submitted.Footnote 11 We assume that under the CL treatment, agents’ foregone payoffs are computed as

Note that the specification of the foregone payoffs is a strong assumption about the individual behavior which may affect results of the IEL. There are other possible mechanisms to compute the foregone payoffs under the closed book. We choose this specific mechanism because of its close resemblance to the mechanism used in Arifovic and Ledyard (2007).

Under the OP treatment, an agent knows the state of the order book at every moment of the previous trading session. Assuming that his arrival time does not change, the agent can find a price of a (notional) transaction, \(p^*_{\cdot,t}(\varepsilon_{\cdot})\), for any alternative message ε · and compute his own payoff using Eq. 2.1. Thus, the foregone payoffs under OP treatment are given by

with corresponding information sets \(\mathcal{I}^\text{OP}_{b,t}, \mathcal{I}^\text{OP}_{s,t} \subset \mathcal{I}_t\).

Selection of a message from the pool

When the new pool is formed, one of the messages is drawn randomly with a selection probability and the corresponding order is submitted for trading session t + 1. The selection probability is also based upon foregone payoffs from the previous period. For example, for buyer b the selection probability of each particular message ε b,t + 1 from pool B b,t + 1 is computed as

where \(\mathcal{I}_{t}\) is an information set, which varies depending on the type of market. Under IR all messages have non-negative performances. This guarantees that Eq. 3.2 gives a number between 0 and 1.Footnote 12

Other specifications for selection probabilities are also possible. Popular choices in the literature are discrete choice models (probit or logit type). The logit probability model is popular, for example, in modeling the individual learning in the literature on financial markets with heterogeneous agents (Brock and Hommes 1998; Goldbaum and Panchenko 2010) and has been recently used to explain the results of laboratory experiments (Anufriev and Hommes 2012). We simulated our model with these alternative specifications in order to address the robustness issue of the IEL. The results reported below are affected neither by the functional form of selection probability nor by the value of the intensity of choice parameter of the logit model. This is mostly due to the replication stage which in several rounds replaces most of the strategies in the pool with similar relatively well performing strategies. It is worth pointing out that with our specification of the selection probability, we have one less free parameter, namely, the intensity of choice.

4 Market efficiency under IEL

To study the effects of market transparency on allocative efficiency, we compare the market outcome in two information treatments, closed book and open book. In our simulations performed with learning agents we concentrate on four different aggregate variables: allocative efficiency, session-average price, its volatility and number of transactions. As before we compute the average values of these variables over T = 100 consecutive trading periods after \(\mathcal{T}=100\) transitory periods. To eliminate a dependence on a realization of a particular random sequence we average the above numbers over S = 100 random seeds.

Table 2 summarizes the parameters of the IEL model which we use in the baseline simulation throughout this Section. Notice that the IR is enforced in the baseline treatment.

4.1 GS-environment

Figure 4 shows allocative efficiency under the IEL with CL and OP, respectively, for the GS-environment simulated with n = 3 and n = 10 EMBs. We observe a significant increase in allocative efficiency over the ZI-benchmark shown by dotted line. The solid line indicates the theoretical expected efficiency for n → ∞ derived below. The allocative efficiency under the IEL practically does not depend on n, the number of EMBs. Notice the striking difference caused by transparency of the book. The allocative efficiency is higher under the OP treatment, actually very close to 100% for any β, while under the CL treatment there is a positive linear dependence between the efficiency and β for β > 0.

Figures 5 and 6 show the evolution of the market during the first 100 trading sessions for β = 0.1 and β = 0.5, respectively. Upper panels show the evolution of market price and efficiency under CL (left panel) and OP (right panel) treatment. Horizontal lines indicate β on the price panel and 100% efficiency on the efficiency panel. Consistently with the long-run results of Fig. 4 the price is much more volatile under the CL and is stable and close to β under the OP. The efficiency is permanently changing between β and 1 under CL for both values of β. On the contrary, under OP the efficiency is only initially changing between β and 1, but then converges to 1. An outlier in period 91 for β = 0.5 on Fig. 6b is the result of agents’ experimentation, as discussed below.

Dynamics in the GS-environment with 3 EMBs with β = 0.1. The horizontal lines indicate β on the panel for price and 100% efficiency on the panel for efficiency. In the right part of panels (c) and (d) the stars denote valuations/costs of agents and the vertical line shows the equilibrium price range

Dynamics in the GS-environment with 3 EMBs with β = 0.5. The horizontal lines indicate β on the panel for price and 100% efficiency on the panel for efficiency. In the right part of panels (c) and (d) the stars denote valuations/costs of agents and the vertical line shows the equilibrium price range

In order to explain these results for the aggregate market outcomes we look at the individual strategies of agents and their evolution. An important question is whether and where the IEL-driven individual strategies converge under different treatments. In panels (c) and (d) of Figs. 5 and 6, we show the evolution of individual bids and asks for both buyers and sellers. Agents’ valuations/costs are denoted by stars in the right part of the plots; the range of equilibrium prices is indicated by a vertical line.

Closed book treatment

Consider the CL treatment shown in Figs. 5c and 6c. The orders submitted by the intramarginal traders converge to their valuations/costs. All other traders (i.e., extramarginal buyers) exhibit somewhat erratic behavior often changing their submitted orders but now and then submitting orders very close to their valuation β. Analysis of the evolution of the individual pools reveals that after a short transitory period the pools of all traders become almost homogeneous (except for deviations due to experimentation) and consist of messages that are close to their own valuations/costs. In the following result we state that the profile with pools consisting of such messages is “attractive”. The word “attractive” is used not in the strict sense of convergence of the dynamical system to some state. In fact, the IEL never converges because of the non-vanishing noise of the experimentation stage. We refer to the strategy profile as “attractive”, if any single mutant message added to this profile at the experimentation stage will not increase its presence in the pool, but will be replaced in the long run by a message, which is arbitrary close to the message from the initial profile.

Result 1

The strategy profile under which the pool of every trader consists of messages equal to his own valuation/cost is attractive under the CL treatment in the GS-environment.

We explain this result as follows. Consider the rule for the foregone payoffs (Eq. 3.1), which agents use in their learning procedure. Under the GS-environment there is only one price during the trading session, \(p_t=P_t^{av}\). After this price is realized each buyer (seller) receives the same nonnegative payoff for any allowed message above (below) p t and zero payoff for all other messages. Suppose now that the pool of every agent consists only of his valuations/costs, and that one of the agents, say an EMB, has a mutant strategy, ε b ′ < β, in his pool. Observe, that for any transaction price p the foregone payoff of the mutant is no larger than the foregone payoff of the incumbent message, β. Indeed, when p ∈ (ε b ′, β), the payoff of the mutant is 0, and the payoff of the incumbent is β − p > 0. For every other price the payoffs are the same, 0 for p ≥ β and β for p ≤ ε b ′. Hence, the mutant cannot increase the probability of its presence in the pool in the subsequent periods. For instance, until no new mutations to the initial profile occur, the transaction price can beFootnote 13 1, β, ε b ′, or 0. In all these cases all the messages in the EMB’s pool (i.e., β and ε b ′) receive the same payoffs and the mutant is expected to occupy exactly one place in the pool after the replication.

Furthermore, the mutant must eventually leave the pool after a mutated message ε′′ ∈ (ε b ′, β) enters the pool of the same or other trader. At a period, when this message determines the transaction price (such period comes about with probability 1, since every sequence of traders’ arrival has equal, non-zero probability), the incumbent message β of our EMB receives higher payoff than the mutant message ε b ′. The mutant does not survive the replication stage. In case if the message ε′′ belongs to the pool of the same trader, this new mutant may “replace” the old mutant in the pool. The same reasoning implies, however, that the new mutant will also be replaced in the long-run either by the incumbent message β or by other mutant from the interval (ε′′, β). Only mutations towards the initial configuration will survive in the long run, explaining the “attractiveness” of the initial profile.

The same reasoning holds for other types of traders.

Result 1 has the following consequence for the efficiency.

Corollary 1

Under the configuration in Result 1 the price oscillates in the range [0, 1], and the expected efficiency is given by

Proof

See Appendix. □

When number of agents n → ∞ the expression 4.1 converges to (1 + β)/2, shown by a solid line in Fig. 4a. Notice that the evolution of submitted orders in the CL treatment (see Figs. 5c and 6c) is not fully consistent with Result 1 due to persistent experimentations. A noise due to experimentation is especially strong for the EMBs because the mutants in their pools will be wiped out by the counterfactual analysis only after periods with sufficiently low transacted price, which are relatively rare.

Open book treatment

Let us turn now to the OP treatment, where the evolution of individual strategies is remarkably different. In Figs. 5d and 6d we observe that intramarginal traders are able to coordinate on one price which remains unchanged for a long period and submit the orders predominantly at this price. In the following result we show that the profile with pools consisting of messages equal to any given equilibrium price can, with a large probability, be “sustained” in the sense that any single mutant message added to this profile will be replaced by the message from the initial profile. There is a small probability, however, that a chain of mutations will force agents to jump out of this profile and coordinate on a similar homogeneous profile but with another price from the equilibrium range.Footnote 14

Result 2

For any price p from the range (β, 1) the strategy profile under which the pools of the IMB and the IMS consist of messages equal to this price can be sustained with a high probability under the OP treatment in the GS-environment.

To explain this result, let us suppose that both intramarginal traders have homogeneous pools with messages equal to p ∈ (β, 1) . Given these pools, the realized price is p. Assume that during the experimentation stage a mutant message is introduced in the pool of the IMB and/or the IMS. Consider the replication stage immediately after the experimentation. For any mutant message of the IMS, ε s ′, such that ε s ′ > p, no counterfactual transaction is possible implying 0 foregone payoff for the mutant. Similarly, any mutant message of the IMB, ε b ′, such that ε b ′ < p, will have 0 foregone payoff. Hence, these mutants will not survive the replication stage, and will not be present in the pools during the subsequent session. In case, when ε s ′ < p or ε b ′ > p, the sequence of traders’ arrival in the previous (pre-mutation) session becomes important. With probability 1/2 the IMB arrived before the IMS. In this case the counterfactual order of the IMB determines the counterfactual transaction price. Hence, the mutant of the IMB, ε b ′, will yield a smaller foregone payoff than the original message, p, and will be eliminated at the replication stage. The mutant of the IMS, ε s ′, attains the same level of the foregone payoff as the original message. The analysis of the case when the IMS arrived before the IMB is analogous.

We have shown that every mutation can, on average, occupy less than one place in the pools of the next session. Furthermore, only the IMS’s mutations towards the lower price and the IMB’s mutations towards the higher price have a chance to be present in the new pool. Under our rule for the foregone payoff, these mutations either bring strictly smaller payoff than the incumbent message, p, or the same payoff (when they do not determine the transaction price). Hence, in the long run the mutants are likely to be replaced by the original messages, given that the original messages are still present in the pools of every intramarginal trader.

There is a chance that the original pool will be completely abandoned through a chain of mutations, so that the return to the original profile becomes impossible. However, this chance is very small. Through the analysis of all possible outcomes, one can find the most probable scenario for such profile jump. Let us assume that the original mutant of the seller, ε s ′ < p, that survived the replication stage, was selected as an order for one of the subsequent sessions and determined the transaction price of this session. Under these circumstances, the IMB can generate a mutant ε b ′′ ∈ (ε s ′, p) surviving the replication stage. If in the next period this mutant is submitted as an order of the IMB along with the incumbent message p of the IMS, there will be no trade. Now all the messages and mutations, which can facilitate counterfactual trade, e.g. increasing bid and decreasing ask, will receive relatively high foregone payoff and will have a high chance to be selected in the subsequent round. It means that after the following replication messages equal to p or larger will increase their presence in the pool of the IMB, while messages equal to ε s ′ or smaller will increase their presence in the pool of the IMS. In this way, the IMS may abandon its initial profile. The probability of such chain of events is of the order ρ 2/J 2, since two mutations and their choice from the profiles are needed.

According to Result 2 the IEL can converge to any price within the equilibrium range. The jumps within the equilibrium range may occur with a small probability, but all such “multiple equilibria” are equivalent from the efficiency point of view.

Corollary 2

Under the configuration in Result 2 the price is constant and the expected efficiency is given by

Proof

Since the strategy profiles of the IMB and the IMS are constant, the price is also constant. Given the price in the competitive equilibrium range the IMB trades with the IMS and the maximum expected efficiency, E OP = 1, is obtained for any β. □

This result is consistent with our simulations. For example, in Fig. 6d the strategies of the IMB and IMS converged to the same submitted orders approximately equal to 0.53. Notice that the EMBs never trade in such a market and all their strategies in the pools have equal probabilities which leads to random bids fluctuations in [0, β] region, see the lower panel of Fig. 6d.

Even if Result 2 implies the 100% allocative efficiency, due to experimentation the efficiency may drop in some periods. This happens around the period 91 in Fig. 6d. After previous trading round the seller’s pool was dominated by the orders equal to 0.53, which is the price at period 90. An experimentation adds a strategy 0.06 to the seller’s pool, which survives replication stage. In fact, the price p 90 was determined by the buyer’s order (the seller at t = 90 arrived after the buyer) and so all the strategies below p 90 have the same hypothetical payoffs. Even if the strategy 0.06 belongs to the seller’s pool at time 91, a probability to use this strategy as an order is only 1/J = 1/100. Whenever such order is submitted, the price will be lower than previously observed 0.53. In this particular case, p 91 = 0.28 equal to the order of one of the EMB. Notice that after this trading round, the seller will re-evaluates his strategies, and strategy 0.53 will have higher hypothetical payoff than 0.06.

To summarize, the information used by the agents under the IEL shapes their strategy pool in the long-run. This pool affects the aggregate dynamics, which feeds back by providing a ground for selection of active strategies within the pool. When the book is closed (CL treatment), agents react on commonly available signal (price of the transaction) and learn to submit their own valuations/costs. This leads to higher opportunity of trade, but also to larger price volatility, as we observed in Figs. 5a and 6a. When the book is open (OP treatment), active agents can adapt to the stable strategies, always submitting their previous orders. Such individual behavior results in a stable price behavior at the aggregate level.

Figure 7 shows the average price and price volatility under CL and OP treatments and also compares them with ZI outcomes. In accordance with Result 2 under OP treatment the price belong to the competitive price range (denoted by shaded area) for any β. This is not the case for the CL and ZI treatments. When the book is closed and equilibrium combination described in Result 1 is reached, the price jumps between 0, 1 and β and its average falls into the competitive range (β, 1] only when β is small. If the traders are ZI and β is small the price will most certainly be determined by the best among the bids of the IMS and IMB, which is around 1/2. When β is higher, the best bid of the EMBs available to the IMS will determine price more often, resulting in larger average price. However, this bid is smaller than β for finite n, explaining why the price is not in the equilibrium range. The realized volatility will be almost zero under the OP treatment, as implied by Corollary 2. It is the largest in the CL treatment, when its jumps have the largest amplitude.

4.2 S5- and AL-environments

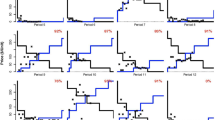

Do the results about aggregate dynamics and individual behavior observed in the stylized GS-environment also hold under alternative environments? Figure 8 shows market aggregates (price, efficiency and number of transactions), as well as evolution of the individual trading orders (bids/asks) over time for the S5-environment, and Fig. 9 gives the same information for the AL-environment. Two horizontal lines on the panels for price indicate equilibrium price range, while the line on the panel for transactions shows the equilibrium number of transactions equal to 4.

Dynamics in the S5-environment. Horizontal lines indicate equilibrium price range on the panel for price, equilibrium efficiency on the panel for efficiency and equilibrium number of transactions on the panel for transactions. In the right part of the plots for individual strategies stars denote valuations/costs of agents and vertical line shows equilibrium price range

Dynamics in the AL-environment. Horizontal lines indicate equilibrium price range on the panel for price, equilibrium efficiency on the panel for efficiency and equilibrium number of transactions on the panel for transactions. In the right part of the plots for individual strategies stars denote valuations/costs of agents and vertical line shows equilibrium price range

Notice that the qualitative results are very similar for S5 and AL environments. Similarly to the GS-environment, the price is less volatile under the OP treatment and lies within the equilibrium range, while in case of the CL treatment the price is often outside the equilibrium range. The efficiency under the CL treatment is systematically below 1, while under OP treatment it is virtually 1 most of the time. Interestingly, a loss of efficiency under the CL is attributed to overtrading, i.e., larger than equilibrium number of transactions. This is simply a consequence of larger than equilibrium range of price fluctuations, which contains the valuations/costs of the extramarginal traders making their trading possible. Under the OP treatment the loss of efficiency occurs due to smaller than equilibrium number of transactions. The EMB and the EMS do not trade under the OP, but occasional experimentation by the intramarginal traders may prevent them from transacting.

As for the individual strategies, under the OP (Figs. 8d and 9d) the intramarginal traders coordinate on one price as we have already seen in the GS-environment. Result 2 still holds. However, under the CL (Figs. 8c and 9c) traders’ orders converge to their valuations/costs only if the latter fall within the range of price fluctuations. It follows from Eq. 3.1 that the IEL process creates an upward pressure only on those buy orders which lie below average price of the last trading session, \(P^{av}_t\), and downward pressure only on those sell orders which lie above \(P^{av}_t\). Whereas in the GS-environment only one transaction per session is possible and the “average” price reflecting this transaction fluctuates within the whole range of [0, 1], in the AL-environment the price \(P^{av}_t\) averages out the individual orders. It leads to smaller range of fluctuation and does not allow traders with extreme valuations/costs to learn. A similar feature is observed in other learning models which do not rely on the common knowledge assumption (see, e.g., Fano et al. 2011).

5 Robustness

5.1 Role of individual rationality

Gjerstad and Shachat (2007) argue that one of the key conditions for high allocative efficiency under the ZI traders in Gode and Sunder (1993) are the constraints on individual rationality.Footnote 15 In this section we investigate whether the assumption of Individual Rationality plays an important role under the IEL learning. It turns out that, in general, our findings of the long run outcome of the IEL learning mechanism are robust towards a violation of the IR constraints by agents. In fact, the behavior violating the IR constraints will often lead to messages with negative foregone payoff. Under the IEL the agents have enough intelligence to discard these messages on the replication or selection stage. Nevertheless, occasionally the messages violating IR will be submittedFootnote 16 obviously leading to higher price volatility. We are interested also in the effect of these messages on efficiency.

Figure 10 shows the results of simulation of the GS-environment with n = 3 and n = 10 EMBs populated by agents relying on the IEL but without IR. For every β both in the CL treatment (left panel) and in the OP treatment (right panel) the resulting efficiency is very close to the theoretical level found in Corollaries 1 and 2. Comparison with Fig. 4 shows that for the IEL learning the IR constraints in the message generating process are almost irrelevant.

Comparison of Fig. 11 with Fig. 8 for the S5-environment and Fig. 12 with Fig. 9 for the AL-environment reveals an interesting effect of the removal of individual rationality constraints. First of all, we observe higher volatility of submitted orders and, therefore, in price, in both treatments, CL and OP. Under the CL this higher volatility slightly promotes learning of agents’ valuations/costs. As a result more often we observe the sessions with overtrading. Under the OP, absence of the IR impairs the coordination to one price, often leading to undertrading. Both scenarios result in lower efficiency than in simulations with IR. It is important to stress that the resulting loss of allocative efficiency is moderate: it is much lower than the loss observed in simulations with the ZI traders.

Dynamics in the S5-environment without IR. The horizontal lines indicate the equilibrium price range on the panel for price, the equilibrium efficiency on the panel for efficiency and the equilibrium number of transactions on the panel for transactions. In the right part of the plots for the individual strategies the stars denote the valuations/costs of agents and the vertical line shows the equilibrium price range

Dynamics in the AL-environment without IR. The horizontal lines indicate the equilibrium price range on the panel for price, the equilibrium efficiency on the panel for efficiency and the equilibrium number of transactions on the panel for transactions. In the right part of the plots for the individual strategies the stars denote the valuations/costs of agents and the vertical line shows the equilibrium price range

5.2 The role of IEL parameters

The IEL algorithm has two important parameters, the size of the pool of strategies, J, and the probability of experimentation, ρ. Since the values of these parameters are chosen in an ad hoc way, it is important to investigate the robustness of the results to these parameters. For the S5- and AL-environment, respectively, Tables 3 and 4 summarize the efficiency, price, price volatility and number of transactions for different combinations of the probability of experimentation, ρ, and the size of the strategy pool, J.

Our finding that the price volatility and trading volume depend on the information treatment turn out to be robust to parameter variation. In particular, the price is less volatile under the OP treatment than under the CL treatment for any combination of ρ and J in both environments. Also independent on the values of parameters, we observe overtrading in the CL treatment and undertrading in the OP treatment. These are the consequences of the different evolutions of strategy profiles under different treatment and can be best understood with the help of Results 1 and 2, obtained for a simpler GS-environment. But what can be said about the allocative efficiency? Both overtrading and undertrading lower efficiency but for different reasons and the precise consequence for allocative efficiency depend mostly on the configuration of demand and supply but also on the parameters. Overtrading is more detrimental for the S5-environment because of the larger number of the extramarginal traders and the higher potential efficiency loss. In the S5-environment for ρ ≤ 0.1 the efficiency in the OP treatment is larger than the efficiency in the CL treatment (the only exception is ρ = 0.01, J = 10). For large probability of experimentation the efficiency in the OP drops significantly and becomes lower than the efficiency in the CL. On the contrary, in the AL-environment the CL market has a higher efficiency than the OP market for most of the parameter values (two exceptions are obtained when ρ = 0.1 and J = 100 or J = 200).

6 Conclusion

This paper contributes to the issue of market design by analyzing the role of transparency. We focus on the market organized as a continuous double auction with an order book, and study the consequences of the use of full or limited information derived from the order book of a previous period. A fully rational behavior is extremely difficult to model in such a market, while the opposite extreme of Zero-Intelligent behavior cannot capture informational differences in market architecture. We choose an intermediate approach and model our traders as boundedly rational learning agents, whose strategies evolve over time. The learning is modeled through the Individual Evolutionary Learning algorithm of Arifovic and Ledyard (2004, 2011), which incorporates two Darwinian ideas. First is experimentation, which means that agents are allowed to use, in principle, any strategy at some period of time. Second is selection with reinforcement, so that strategies with higher past payoffs have higher probability to be used in the future. An important aspect of the IEL is that every agent evaluates the strategies not only on the basis of the actual, but also counterfactual (foregone) payoff.

We derive allocative efficiency for the benchmark case with the ZI traders and show through simulations that IEL leads to a substantially higher efficiency. As for the transparency issue we show that strategies learned by traders are remarkably different in the treatments with fully available (“open”) order book and unavailable (“closed”) order book. Traders, who systematically participate in the trade, learn to submit their own valuations/costs under the closed book treatment, and the previously observed trading price under the open book treatment. These individual differences result in differences at the aggregate level: higher price volatility and overtrading under the closed book relative to the open book treatment. Allocative efficiency is comparable in both cases, however the sources of the inefficiencies are different.

We show that our results are robust with respect to the market environments that we consider. In addition, the results are robust with respect to changes in the values of the parameters of the learning model, such as the rate of experimentation and the size of the pool of strategies. We also find that the IEL algorithm is effective in wiping out the strategies which contradict individual rationality constraint and which would result in a strictly negative payoff. This is an important property of the algorithm, suggesting that it can be successfully applied in more sophisticated environments, where strategies with negative performance cannot be easily identified and ruled out at the outset. Indeed, as experiments in Kagel et al. (1987) and Lei et al. (2001) show, in reality participants occasionally violate the individual rationality requirement and trade with clear losses. The learning model applied in this paper does not contradict such experimental evidence.

In modeling agents’ behavior our approach is relatively simple in comparison to some micro-structure studies attempting to model fully rational behavior. However, our behavioral assumptions fit better to the experimental evidence of human behavior in complex environment that demonstrates that human subjects often use simple behavioral rules (Hommes et al. 2005). Based on such assumptions our model predicts that volatility in the market should decrease as a result of higher transparency. This is consistent with the study of Boehmer et al. (2005) for the NYSE. Some of their finding (e.g., higher order splitting as a result of increasing market transparency) cannot be replicated in this paper, because we do not allow individual traders to buy or sell multiple units. Several other assumptions of this paper could also be relaxed. Allowing for cancelation of some orders would bring us to a more realistic setting, which lies in between of the two extremes: no-cancelation as in this paper and cancelation of all remaining orders after every transaction as in Gode and Sunder (1993). Submission of multiple orders would allow us to model a more realistic intermediate situation between the two extremes: one-order per agent in one trading session as here and unbounded amount of multiple orders as in Gode and Sunder (1997). Finally, it would be also interesting to consider endogenous dynamics for valuations and costs, explored in heterogeneous agent models literature, see, e.g., Brock and Hommes (1998) and Anufriev and Panchenko (2009).

Notes

See closely related research in Fano et al. (2011) for an application of the GA to the CDA and batch auction market with a large number of traders.

Alternatively, as pointed out by one of the referees, this finding can be formulated as follows. The agents participating in trade learn to be approximately “price-makers” when the information is full and learn to be approximately “price-takers” when the information is limited. Fano et al. (2011) use this terminology.

The matlab codes used to generate the results of this paper are available from http://research.economics.unsw.edu.au/vpanchenko/software/IELmatlabcodes.zip.

This is guaranteed by assuming that in a special case when there exists a buyer whose reservation value coincides with the cost of a seller, these traders exchange maximum possible quantity.

The ceiling function, ⌈x ⌉, gives the smallest integer greater than or equal to x.

The valuations/costs are V 1 = 1, V 2 = 0.93, V 3 = 0.92, V 4 = 0.81, V 5 = 0.5, C 1 = 0.3, C 2 = C 3 = 0.39, C 4 = 0.55 and C 5 = 0.66. First four buyers and sellers are intramarginal. The equilibrium quantity is 4 and equilibrium price range is [0.55, 0.66).

Each trading session can be thought as a trading “day”.

This assumption implies that multiple rounds of bidding are excluded from the analysis in this paper. Gode and Sunder (1997) show that multiple rounds (until all possible transactions occur) result in higher efficiency due to the absence of losses caused by an absence of trade. We also do not clear and “resample” the book after every transaction. Resampling would increase efficiency of the market, because orders submitted far from the equilibrium range of price would have a chance to be corrected, see LiCalzi and Pellizzari (2008).

In using this benchmark we attempt to abstract from agents’ behavioral aspects. One needs to be careful, however, since ZI in itself is also a very special type of behavior.

Another plausible possibility is to consider the closing price of the day. This modification does not influence our qualitative results.

Recall that given the submitted orders, the price of transaction depends on the sequence of traders’ arrival.

Comparing with Result 1 for the CL treatment, notice that, on the one hand, there is a continuum of “equilibrium” profiles under OP, leading to a possibility of abandoning any given profile. On the other hand, when the profile is not abandoned, the mutations are replaced by the messages from the original profile, not by the messages close to the original messages. This explains why we use a notion stronger than “attractiveness”.

Recall that we confirm this claim in the GS-environment only for the case when the EMBs’ valuation \(\beta<\sqrt{2}-1\), see Fig. 2b.

There is an experimental evidence that profit-motivating subjects do violate the IR constraints, even if rarely. See, for example, Lei et al. (2001).

References

Anufriev M, Hommes C (2012) Evolution of market heuristics. Knowl Eng Rev (forthcoming)

Anufriev M, Panchenko V (2009) Asset prices, traders’ behavior and market design. J Econ Dyn Control 33:1073–1090

Arifovic J (1994) Genetic algorithm learning and the cobweb model. J Econ Dyn Control 18(1):3–28

Arifovic J, Ledyard J (2004) Scaling up learning models in public good games. J Public Econ Theory 6(2):203–238

Arifovic J, Ledyard J (2007) Call market book information and efficiency. J Econ Dyn Control 31(6):1971–2000

Arifovic J, Ledyard J (2011) A behavioral model for mechanism design: individual evolutionary learning. J Econ Behav Organ 78(3):374–395

Boehmer E, Saar G, Yu L (2005) Lifting the veil: an analysis of pre-trade transparency at the NYSE. J Finance 60(2):783–815

Brock WA, Hommes CH (1998) Heterogeneous beliefs and routes to chaos in a simple asset pricing model. J Econ Dyn Control 22(8–9):1235–1274

Camerer CF, Ho T-H (1999) Experienced-weighted attraction learning in normal form games. Econometrica 67(4):827–874

Duffy J (2006) Agent-Based Models and Human Subject Experiments. In: Judd K, Tesfatsion L (ed) Handbook of computational economics, vol 2. Agent-Based Computational Economics Elsevier, North-Holland (Handbooks in Economics Series)

Easley D, Ledyard J (1993) Theories of price formation and exchange in double oral auctions. In: Friedman D, Rust J (ed) The double auction market: institutions, theories, and evidence. Perseus Books, pp 63–97

Erev I, Roth A (1998) Predicting how people play games: reinforcement learning in experimental games with unique, mixed strategy equilibria. Am Econ Rev 88(4):848–881

Fano S, LiCalzi M, Pellizzari P (2011) Convergence of outcomes and evolution of strategic behavior in double auctions. J Evol Econ. doi:10.1007/s00191-011-0226-4

Foucault T, Kadan O, Kandel E (2005) Limit order book as a market for liquidity. Rev Financ Stud 18(4):1171–1217

Friedman D (1991) A simple testable model of double auction markets. J Econ Behav Organ 15(1):47–70

Gjerstad S, Shachat J (2007) Individual rationality and market efficiency. Working Papers No 1204, Institute for research in the behavioral, economic, and management sciences, Purdue University

Gode D, Sunder S (1993) Allocative efficiency of markets with zero-intelligence traders: market as a partial substitute for individual rationality. J Polit Econ 101(1):119–137

Gode D, Sunder S (1997) What makes markets allocationally efficient? Q J Econ 112(2):603–630

Goldbaum D, Panchenko V (2010) Learning and adaptation’s impact on market efficiency. J Econ Behav Organ 76(3):635–653

Hommes C, Sonnemans J, Tuinstra J, Velden Hvd (2005) Coordination of expectations in asset pricing experiments. Rev Financ Stud 18(3):955–980

Kagel J, Harstad R, Levin D (1987) Information impact and allocation rules in auctions with affiliated private values: a laboratory study. Econometrica 55(6):1275–1304

Ladley D (2012) Zero intelligence in economics and finance. Knowl Eng Rev (forthcoming)

Lei V, Noussair C, Plott C (2001) Nonspeculative bubbles in experimental asset markets: lack of common knowledge of rationality vs. actual irrationality. Econometrica 69(4):831–859

LiCalzi M, Pellizzari P (2008) Zero-intelligence trading without resampling. In: Schredelseker K, Hauser F (ed) Complexity and artificial markets. Springer, pp 3–14

Satterthwaite M, Williams S (2002) The optimality of a simple market mechanism. Econometrica 70(5):1841–1863

Smith VL (1962) An experimental study of competitive market behavior. J Polit Econ 70(2):111–137

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two referees for their thorough reading of the paper and numerous useful suggestions. We thank the participants of the workshop “Evolution and market behavior in economics and finance” in Pisa, the SCE-2009 conference in Sydney, and the seminars at the University of Amsterdam, University of Auckland, Concordia University, Montreal, Simon Fraser University and the University of Technology, Sydney, for useful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Mikhail Anufriev acknowledges the financial support by the EU 7th framework collaborative project “Monetary, Fiscal and Structural Policies with Heterogeneous Agents (POLHIA)”, grant no. 225408. Jasmina Arifovic acknowledges financial support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council under the Standard Research Grant Program. Valentyn Panchenko acknowledges the support under Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (project number DP0986718). Usual caveats apply.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Definition of the frequently used acronyms

Acronym | Definition | Explained in |

|---|---|---|

CDA | Continuous double auction | Section 2.2 |

ZI | Zero intelligent (agent) | Section 2.3.1 |

IR | Individual rationality | Section 2.3.1 |

IEL | Individual evolutionary learning | Section 3 |

AL | Environment from Arifovic and Ledyard (2007) | Section 2.1 |

GS | Environment from Gode and Sunder (1997) | Section 2.1 |

S5 | Symmetric environment with 5 buyers and 5 sellers | Section 2.1 |

OP | Open book (treatment) | Section 3 |

CL | Closed book (treatment) | Section 3 |

IMB | Intramarginal buyer | Section 2.1 |

IMS | Intramarginal seller | Section 2.1 |

EMB | Extramarginal buyer | Section 2.1 |

EMS | Extramarginal seller | Section 2.1 |

Proof of Proposition 2.1

First, let us consider ZI agents with IR. We have three types of traders:

-

one intramarginal buyer (IMB) whose valuation is 1 and whose bid price is drawn from the uniform distribution on [0, 1];

-

one intramarginal seller (IMS) whose valuation is 0 and whose ask price is are drawn from the uniform distribution on [0, 1];

-

an infinite number of extramarginal buyers (EMBs) whose valuations are β and whose bid prices are drawn from the uniform distribution on [0, β].

In the proof we rely on the following arguments. Because the order of arrival of all traders is random, when number of the EMBs n → ∞, the number of the EMBs arriving before the IMS becomes sufficiently large with probability 1. Since the number of the EMBs arriving prior to the IMS is sufficiently large, the best (highest) bid price among these EMBs converges to β with probability 1. This bid is the best available order of the opposite side for the IMS, unless the IMB arrives prior to the IMS and outbids the highest EMBs’ bid by submitting bid b > β. The same line of reasoning is used in the proof of a similar proposition in Gode and Sunder (1997).

We consider, in turn, all possible outcomes of a trading session, evaluating probability of each outcome and its allocative efficiency. Below we distinguish between two equiprobable outcomes (the IMB arrives before the IMS and vice versa) and then compute the (conditional) probabilities of every single event.

-

1.

the IMB arrives before the IMS. This event occur with probability \(\frac{1}{2}\). The further development depends on whether the IMB outbids the EMB with the highest bid β:

-

(a)

the IMB bids b < β. Since the IMB is ZI, this event occurs with probability β. But the highest EMBs’ bid is β, hence the IMB fails to outbid the EMB with the highest bid. Two possibilities arise:

-

i.

the IMS asks a < β with P = β - the IMS trades with the EMB; efficiency is β, or

-

ii.

the IMS asks a > β, P = (1 − β) - no transaction occurs; efficiency is 0.

-

i.

-

(b)

the IMB bids b > β with P = (1 − β) - the IMB outbids the EMB, and

-

i.

the IMS asks a < β with P = β - then the IMB trades with the IMS; efficiency is 1, or

-

ii.

the IMS asks a > β and \(a < \textrm{IMB } b\) with P = (1 − β)/2 - then the IMB trades with the IMS; efficiency is 1, or

-

iii.

the IMS asks a > β and \(a > \textrm{IMB } b\) with P = (1 − β)/2 - the IMS asks is too high, no trade occurs; efficiency is 0.

-

i.

-

(a)

-

2.

the IMB arrives after the IMS with P = 0.5,

-

(a)

the IMS asks a < β with P = β - the EMB trades because the IMB did not have a chance to outbid it; efficiency is β, or

-

(b)

the IMS asks a > β with P = 1 − β - none of the EMBs can trade and

-

i.

the IMB bids b < β with P = β - the IMB bids too low, no transaction occurs, efficiency is 0, or

-

ii.

the IMB bids b > β and \(b < \textrm{IMS } a\) with P = (1 − β)/2 - the IMB bids too low, no transaction occurs, efficiency is 0, or

-

iii.

the IMB bids b > β and \(b > \textrm{IMS } a\) with P = (1 − β)/2 - the IMB trades with the IMS; efficiency is 1.

-

i.

-

(a)

Expected efficiency is given by the following expression

Second, we consider the case of ZI agents without IR. In this case there is no difference in bidding behavior between the IMB and EMB traders. Thus, when the number of the EMB traders converges to infinity with probability 1, one EMB will trade. Such trade delivers efficiency β. □

Proof of Corollary 1

A transaction price in the CDA is determined using price/time priority and highly depends on the order of the agents’ arrival. Given that agents bid/ask their valuations/costs and the fact the order of their arrival is randomly permuted, price vary for different trading sessions and, hence, is volatile over time.

To derive Eq. 4.1 we consider the following situations:

-

1.

The IMS arrives first, probability P = 1/(n + 2), and

-

(a)

the IMB arrives next, probability P = 1/(n + 1), and efficiency is 1, or,

-

(b)

the EMB arrives next, probability P = n/(n + 1), and efficiency is β

In this situation the price is 0.

-

(a)

-

2.

The IMB arrives first, probability P = 1/(n + 2), and efficiency is 1. In this situation the price is 1.

-

3.

An EMB arrives first, probability P = n/(n + 2), and

-

(a)

the IMS arrives before the IMB, probability P = 1/2, and efficiency is β, in this situation the price is β, or,

-

(b)

the IMS arrives after the IMB, probability P = 1/2, and efficiency is 1, in this situation the price is 1.

-

(a)

Summing the terms we obtain Eq. 4.1 for the efficiency. □

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Anufriev, M., Arifovic, J., Ledyard, J. et al. Efficiency of continuous double auctions under individual evolutionary learning with full or limited information. J Evol Econ 23, 539–573 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-011-0230-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-011-0230-8