Abstract

Given the ambiguous empirical results of previous research, this paper tests whether support for a climate policy-induced pollution haven effect and the pollution haven hypothesis can be found. Unlike the majority of previous studies, the analysis is based on international panel data and includes several methodological novelties: By arguing that trade flows of dirty goods to less dirty sectors may also be influenced by changes in policy stringency, trade information on primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors are included. In order to clearly differentiate between dirty sectors and sectors with high pollution abatement costs, separate measures for pollution intensity and policy stringency are implemented. For the former, two intensities, namely the sectors’ carbon dioxide emission intensity and the emission relevant energy intensity, are used to identify dirty sectors. For the latter, an internationally comparable, sector-specific measure of climate policy stringency is derived by applying a shadow price approach. Potential endogeneity between climate policy stringency, trade openness and the trade balance is controlled for by employing a dynamic panel generalized method of moments estimator. The results provide evidence for a pollution haven effect that is also present for non-dirty sectors, i.e., a sector’s net imports rise in general if the sector faces an increase in climate policy stringency. Moreover, a stronger pollution haven effect regarding carbon dioxide intensive and emission relevant energy-intensive sectors is revealed. However, no support for the stronger pollution haven hypothesis can be found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Likewise, Ederington et al. (2004) distinguish between a direct and an indirect effect.

A detailed overview of the included countries can be found in Table 4.

The shadow prices of emission relevant energy are also utilized in the subsequent analysis to determine the stringency of climate policy. In Sect. 3.2 the general idea and the estimation procedure of the shadow price approach are introduced. In short, the approach indirectly estimates private sector abatement costs by relying on economic theory and the choices made by firms, revealing their profit maximization behavior. Thereby, the shadow price of a polluting input can be defined as the potential reduction in expenditures on other variable inputs, which can be realized by using additional units of the polluting input while keeping the level of output constant (van Soest et al. 2006). Thus, if a polluting input, which is in the case of this paper emission relevant energy, is weakly regulated, then the price of the polluting input is relatively low and firms will choose to use relatively more of the polluting input. Such shadow prices can be determined by estimating a firm’s or a sector’s cost function.

OECD is short for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Following the definition in the World Input–Output Database (WIOD) the difference between emission relevant energy use and gross energy use is that the former excludes the non-energy use, e.g., asphalt for road building, and the input for transformation, e.g., crude oil transformed into refined products, of energy commodities. While gross energy use is directly linked to expenditures for energy inputs, emission relevant energy use directly relates energy use to energy-related emissions.

The pollution haven effect is measured as the first partial derivative of the economic activity M with respect to the environmental policy stringency P, i.e., \(\partial M/\partial P=\beta _1 \). Hence, a positive and significant coefficient \(\hat{{\beta }}_1 \) implies, ceteris paribus, that increasing the policy stringency results in larger net imports.

In parts empirical studies using panel or time-series data lag the regulatory stringency measure P to see whether strict environmental regulation in the previous period results in changed economic activity (Cole and Elliot 2003).

A more detailed discussion of using average time-invariant policy stringency rather than general time-specific policy stringency is given in Ederington et al. (2004). Similar to their article, the estimates of the final pollution haven Eqs. (4)–(7) in Sect. 5 are not sensitive to this change in specification.

Evidence for the pollution haven hypothesis can be revealed from \(\partial ^{2}M/\left( {\partial TO\partial \bar{{P}}} \right) =\beta _3 \). If the coefficient \(\hat{{\beta }}_3 \) is positive and significant, this implies that an increase in trade openness leads to larger increases in net imports for industries facing relatively higher environmental policy stringencies. As in Eqs. (1) and (2) the pollution haven effect is still determined by \(\partial M/\partial P\).

Alternatively, in particular, tariff rates may be used to measure trade barriers. However, given that a significant number of countries, which this paper analyzes, have signed free trade agreements with each other, tariff rates are not regarded as an appropriate measure. An overview on other trade openness and policy measures is, for example, given in Rose (2004). He classifies 68 different indicators into seven categories, namely outcome-based measures of trade openness, adjusted trade flows, tariffs, non-tariff barriers, informal or qualitative measures, composite indexes, and measures based on price outcomes.

Cole and Elliot (2003) reveal for US industry sectors that pollution-intensive sectors face high pollution abatement costs per value added and are relatively capital intensive.

For instance, in the case of the German support of renewable energies the costs are passed on to clean industries and consumers, whereas energy-intensive firms are partly relieved from the financing and have to pay lower energy prices per kilowatt hour (Diekmann et al. 2012).

As before, the impact of the regulatory stringency determines the pollution haven effect and the pollution haven hypothesis is analyzed based on the impact of the sector- and country-specific but time-invariant average regulatory stringency.

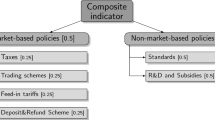

For a detailed overview on the different approaches that researchers have used to measure the stringency of environmental policy and climate policy see Brunel and Levinson (2016) or Althammer and Hille (2016). The former group the approaches into five categories, namely private sector abatement costs, direct assessments of individual regulations, composite indexes, measures based on pollution and energy use, and measures based on public sector expenditures or enforcement.

Equation (8) represents the final specification of the shadow price equation, which is estimated in the system of seemingly unrelated regressions to quantify the measure of climate policy stringency. D is a country-, sector-, and time-specific dummy variable and \(\alpha _\mathrm{E}\) as well as \(\lambda _\mathrm{E}\) are the respective regression coefficients. Given the limited number of degrees of freedom, the time-specific effect is structured in five equivalent three-year time periods.

Further regression estimates are available upon request.

The rankings remain unchanged when the countries are ordered based on the average wedges.

The WIOD data are not used directly to determine the country-level capital stocks, because extrapolating the data using prior growth rates seems problematic given the potential negative consequences of the world financial crisis starting in 2008.

Table 9 in “Appendix 2” provides an overview of the 33 included sectors. The sectors are structured using the division-level ISIC Rev. 3.1. While sector-specific data certainly represent an improvement compared to prior multi-country studies, it needs to be acknowledged that some limitations remain due to the aggregation of sectors.

For instance, if net imports are zero, a regular elasticity of net imports is going to infinity.

In Table 10 in “Appendix 3” the elasticities of net imports are for comparison reasons reported for specifications including emission relevant energy use \(x_\mathrm{E}\) only, i.e., for the classic model using the shadow costs of emission relevant energy P and for the augmented models relying on the emission relevant energy use intensity \(x_\mathrm{E}\) /y. Further estimates are available upon request.

References

Aldy JE, Pizer WA (2015) The competitiveness impacts of climate change mitigation policies. J Assoc Env Res Econ 2(4):565–595

Althammer W, Hille E (2016) Measuring climate policy stringency: a shadow price approach. Int Tax Public Finan 23(4):607–639

Althammer W, Mutz C (2010) Pollution havens: empirical evidence for Germany. Paper presented at the 4th World congress of environmental and resource economists, Montreal, 28 June–2 July 2010. http://www.webmeets.com/files/papers/WCERE/2010/1408/PollutionHavensEmpiricalEvidenceGermany.pdf

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Arellano M, Bover O (1995) Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. J Econom 68(1):29–51

Arouri MEH, Caporale GM, Rault C, Sova R, Sova A (2012) Environmental regulation and competitiveness: evidence from Romania. Ecol Econ 81(C):130–139

Baier SL, Bergstrand JH (2007) Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? J Int Econ 71(1):72–95

Baier SL, Bergstrand JH, Feng M (2014) Economic integration agreements and the margins of international trade. J Int Econ 93(2):339–350

Bao Q, Chen Y, Song L (2011) Foreign direct investment and environmental pollution in China: a simultaneous equations estimation. Environ Dev Econ 16(1):71–92

Becker R, Henderson V (2000) Effects of air quality regulations on polluting industries. J Polit Econ 108(2):379–421

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87(1):115–143

Branger F, Quirion P, Chevallier J (2017) Carbon leakage and competitiveness of cement and steel industries under the EU ETS: much ado about nothing. Energy J 37(3):109–135

Brunel C (2016) Pollution offshoring and emission reductions in EU and US manufacturing. Environ Resour Econ. Advance online publication http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10640-016-0035-1

Brunel C, Levinson A (2016) Measuring the stringency of environmental regulations. Rev Env Econ Policy 10(1):47–67

Brunnermeier SB, Levinson A (2004) Examining the evidence on environmental regulations and industry location. J Env Dev 13(1):6–41

Caselli F (2005) Accounting for cross-country income differences. In: Aghion P, Durlauf SN (eds) Handbook of economic growth. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Chung S (2014) Environmental regulation and foreign direct investment: evidence from South Korea. J Dev Econ 108(2014):222–236

Cole MA, Elliot RJR (2003) Determining the trade-environment composition effect: the role of capital, labor and environmental regulations. J Environ Econ Manag 46(3):363–383

Copeland BR (2011) Trade and the environment. In: Bernhofen D, Falvey R, Greenaway D, Kreickemeier U (eds) Palgrave handbook of international trade. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Copeland BR, Taylor MS (2004) Trade, growth, and the environment. J Econ Lit 42(1):7–71

Dechezlepretre A, Sato, M (2014) The impacts of environmental regulations on competitiveness. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment Policy Brief November 2014

Diekmann J, Kemfert C, Neuhoff K (2012) The proposed adjustment of Germany’s renewable energy law: a critical assessment. DIW Econ Bull 6(1):3–9

Dietzenbacher E, Mukhopadhyay K (2007) An empirical examination of the pollution haven hypothesis for India: towards a green Leontief paradox? Environ Resour Econ 36(4):427–449

Ederington J, Minier J (2003) Is environmental policy a secondary trade barrier? An empirical analysis. Can J Econ 36(1):137–154

Ederington J, Levinson A, Minier J (2004) Trade liberalization and pollution havens. Adv Econ Anal Policy 4(2):Article 6

Ederington J, Levinson A, Minier J (2005) Footloose and pollution-free. Rev Econ Stat 87(1):92–99

European Commission (2012) Commission decision of 24 December 2009 determining, pursuant to Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, a list of sectors and subsectors which are deemed to be exposed to a significant risk of carbon leakage. Amended by Commission Decision 2011/745/EU of 11 November 2011 and Commission Decision 2012/498/EU of 17 August 2012

Frankel JA (2009) Addressing the leakage/competitiveness issue in climate change policy proposals. In: Sorkin I, Brainard L (eds) Climate change, trade, and competitiveness: is a collision inevitable?. Brookings Institution Press, Washington

Greenstone M (2002) The impacts of environmental regulations on industrial activity: evidence from the 1970 and 1977 Clean Air Act amendments and the census of manufactures. J Polit Econ 110(6):1175–1219

Grossman GM, Krueger AB (1993) Environmental impacts of a North American free trade agreement. In: Garber PM (ed) The Mexico-U.S. free trade agreement. MIT Press, Cambridge

Harris MN, Kónya L, Mátyás L (2002) Modelling the impact of environmental regulations on bilateral trade flows: OECD, 1990–1996. World Econ 25(3):387–405

He J (2006) Pollution haven hypothesis and environmental impacts of foreign direct investment: the case of industrial emission of sulfur dioxide (SO2) in Chinese provinces. Ecol Econ 60(1):228–245

Holtz-Eakin D, Newey W, Rosen HS (1988) Estimating vector autoregressions with panel data. Econometrica 56(6):1371–1395

International Energy Agency (2013) Energy prices and taxes: end-use prices. http://wds.iea.org/WDS/Common/Login/login.aspx. Cited 04 Feb 2013

Jaffe AB, Peterson SR, Portney PR, Stavins RN (1995) Environmental regulation and the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing: What does the evidence tell us? J Econ Lit 33(1):132–163

Kalt JP (1988) The impact of domestic environmental regulatory policies on U.S. international competitiveness. In: Spence AM, Hazard HA (eds) International competitiveness. Ballinger, Cambridge

Keller W, Levinson A (2002) Pollution abatement costs and foreign direct investment inflows to U.S. states. Rev Econ Stat 84(4):691–703

Lee J-W, Swagel P (1997) Trade barriers and trade flows across countries and industries. Rev Econ Stat 79(3):372–382

Levinson A (1996) Environmental regulations and manufacturers’ location choices: evidence from the census of manufactures. J Public Econ 62(1–2):5–29

Levinson A (2009) Technology, international trade, and pollution from U.S. manufacturing. Am Econ Rev 99(5):2177–2192

Levinson A, Taylor MS (2008) Unmasking the pollution haven effect. Int Econ Rev 49(1):223–254

Managi S, Hibiki A, Tsurumi T (2009) Does trade openness improve environmental quality? J Environ Econ Manag 58(3):346–363

Michel B (2013) Is offshoring driven by air emissions? Testing the pollution haven effect for imports of intermediates. Federal Planning Bureau Working Paper 12-13, Oct 2013

Millimet DL, Roy J (2016) Empirical tests of the pollution haven hypothesis when environmental regulation is endogenous. J Appl Econom 31(4):652–677

Morrison CJ (1988) Quasi-fixed inputs in U.S. and Japanese manufacturing: a generalized Leontief restricted cost function approach. Rev Econ Stat 70(2):275–287

Morrison Paul CJ, MacDonald JM (2003) Tracing the effects of agricultural commodity prices on food processing costs. Am J Agr Econ 85(3):633–646

Mulatu A, Florax RJGM, Withagen C (2004) Environmental regulation and international trade: empirical results for Germany, The Netherlands and the US, 1977–1992. Contrib Econ Anal Policy 3(2):Article 5

Mulatu A, Gerlagh R, Rigby D, Wossink A (2010) Environmental regulation and industry location in Europe. Environ Resour Econ 45(4):459–479

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2012a) 4. PPPs and exchange rates dataset. http://stats.oecd.org/. Cited 24 Sept 2012

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2012b) Monthly monetary and financial statistics (MEI) dataset. http://stats.oecd.org/. Cited 24 Sept 2012

Penn World Tables (2011) Extended Penn World Tables Database Version 4.0. Released Aug 2011

Penn World Tables (2012) Penn World Table Version 7.1. Released Nov 2012

Pritchett L (1996) Measuring outward orientation in LDCs: can it be done. J Dev Econ 49(2):307–335

Rose AK (2004) Do WTO members have more liberal trade policy? J Int Econ 63(2):209–235

Santos-Paulino A, Thirwall AP (2004) The impact of trade liberalization on exports, imports, and the balance of payments of developing countries. Econ J 114(492):F50–F72

Sato M, Dechezlepretre A (2015) Asymmetric industrial energy prices and international trade. Energ Econ 52(S1):S130–S141

Tobey AJ (1990) The effects of domestic environmental policies on patterns of world trade: an empirical test. Kyklos 43(2):191–209

Trefler D (1993) Trade liberalization and the theory of endogenous protection: an econometric study of U.S. import policy. J Polit Econ 101(1):138–160

van Beers C, van den Bergh JCJM (2003) Environmental regulation impacts on international trade: aggregate and sectoral analyses with a bilateral trade flow model. Int J Global Environ Issues 3(1):14–29

van Soest DP, List JA, Jeppesen T (2006) Shadow prices, environmental stringency, and international competitiveness. Eur Econ Rev 50(5):1151–1167

Windmeijer F (2005) A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. J Econom 126(1):25–51

World Input-Output Database (2012a) WIOD environmental accounts. Released March 2012

World Input–Output Database (2012b) WIOD National Input–Output tables. Released April 2012

World Input–Output Database (2012c) WIOD Socio-Economic Accounts. Released Feb 2012

Zellner A (1962) An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests of aggregation bias. J Am Stat Assoc 57(298):348–368

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) in the framework of the project “Climate Policy and the Growth Pattern of Nations” is gratefully acknowledged. Moreover, the author would like to thank two anonymous referees for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Overview of the final variables

See Table 8.

Appendix 2: Sector overview

See Table 9.

Appendix 3: Estimates of the elasticity of net imports for the chemicals and metals sector

See Table 10.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hille, E. Pollution havens: international empirical evidence using a shadow price measure of climate policy stringency. Empir Econ 54, 1137–1171 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-017-1244-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-017-1244-3

Keywords

- International trade

- Pollution havens

- Carbon leakage

- Global pollution

- Environmental policy stringency

- Shadow prices