Abstract

The present paper focuses on the emergence and consequences of the so-called ‘Dogville Effect’, i.e., the negative socioeconomic and spatial impacts caused by radicalization of cultural attitudes in a region. After a conceptual and historical outline of this phenomenon, we present an empirical case, viz. the rise of the ultra-right-wing party in Greece, Chrysi Avgi. We analyze the party’s spatial dispersion and its aftermaths in the period 1993–2015, using both local and regional election results. Spatial-economic controls are derived from the EUI (European University Institute, Florence) regional database. We employ a 2SLS approach (with historical voting results from 1974 as an instrumental variable) and a difference-in-differences approach with a propensity score matching. Our findings show that there exists a cultural persistence in the local share of ultra-right-wing support. The growth in this radicalization, however, is predominantly determined by the shrinking regional household welfare caused by exogenous forces in our model. Finally, the ‘Dogville Effect’, i.e., a further impoverishment of more radicalized localities, seems to be present in Greece, in the vein of the notion of Myrdal’s vicious circles.

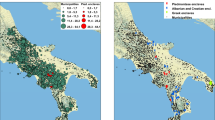

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ calculations

Source: Authors’ own calculations

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The renowned Lars von Trier’s movie ‘Dogville’ has a particularly economically interesting plot that has the following storyline. A young foreign woman, who has her origins in a society with anti-village attitudes but does not share these attitudes, arrives in a small closed world – a village named Dogville. Initially, the woman provides her labor in exchange for food and shelter in a classical supply and demand model. However, her bargaining power on the labor market decreases due to distorted information about her being an outlaw person (actually the truth is she is being chased by her anti-village past associates). The market responds to the shock from this information and her salary is decreased. Over time, her economic and, gradually, also her social rights deteriorate. Ultimately, the basic minimum of human dignity is breached – the young woman is brought to bartering her body in exchange for shelter under complete loss of personal freedom (she agrees to be kept chained, as part of the transaction). This shocking marginalization of the woman leads her to take a radical turn in her choices. She decides to cooperate with her own old enemies (from whom she was trying to escape at her first place when coming to seek shelter in Dogville). Together with them, she sets on fire and completely destroys the place ‘Dogville’ which had impoverished her beyond the minimum threshold of acceptability.

We assume that the radical response to a negatively changing economic context (e.g., a shock) is morally not sanctioned owing to what is known in behavioral economics as a fudge factor or in Becker’s (1968) economic interpretation as a moral cost–benefit analysis. Clearly, the above mentioned local ‘tunnel effect’ activates the drive (Herzog 2015) for basic survival. And therefore, people may even perceive their increased aggressiveness/hostility as morally justifiable under extreme conditions that previously would have been regarded as excessive (Dharmapala et al. 2009; Becker 1968). The moment that the previously unthinkable moral constraint switches to another level of tolerance or acceptance is an illustration of a classical tipping point (Lamberson and Page 2012). This is the tipping point at which we assume that the mechanism of the above mentioned ‘tunnel effect’ starts operating. There are other potential mechanism through which radicalization may be affecting negatively local economic productivity.

As mentioned above, one highly plausible such mechanism might be the impact of cultural gravity on the human capital accumulation in a place and migration (see Tubadji and Nijkamp 2015), where the radicalization of the place decreases the attractiveness of a place for footloose human capital. Alternatively, the cultural impact on growth through the six degrees of connectedness in the social network which affects local innovation (see Tubadji and Nijkamp 2016 for an extensive description of this potential channel) might be the way how radicalization decreases the connectedness in the social network and thus makes a place less innovative and therefore less economically prosperous. Also, many other known or novel economic mechanisms sensitive to cultural impact may be affected by radicalization and thus generate a serious impact on local economic development.

Alternatively, we re-estimated all tests with the share of voters for the ultra-left party KKE as a dependent variable. The results however, were never statistically significant for the KKE-related variables. The rest of the model was stable and performed similar to the reported results employing the percentage voted for the Chrisi Avgi. On the one hand, a reason for this may be the Greek specific reality, where the origin of the left and right parties and their relation with the Monarchy from the past might be carried further in time by cultural persistence. It could be also that there is something more universal in the ethos of the right and left political ideologies, that can be generalized outside the Greek context. Namely, left ideology might be associated with concern for the common good and right ideology is more concerned with the private interest. There is work related to this matter suggesting that places with less risk-averse attitudes are more prone to develop populist political preferences (see Pastor and Veronesi 2018). This matter is worth further investigation before a definite answer for the reasons behind the different results obtained with ultra-left and ultra-right voting can be stated.

We conducted all estimations alternatively using the dummy variable capturing the start of the austerity period as an approximation for the negative economic shock. These results appeared to be very consistent with the ones presented here.

The results obtained with the use of the two alternative measures are consistent. The results using the adjusted budget deficit are only more prominent as magnitudes.

The sectoral location quotient (LQ) is a measure of concentration of a particular industry in a region compared to the national average presence of this industry. We have these calculated on NUTS3 level and they are obtained following Florence (1939) using the formula:

$$ IS = (Es/Est)/(Er/Et), $$(1)where IS represents the specialization index; Es stands for local employment in the given sector of interest; Est represents the employment in this sector in the country; Er stands for total local employment in all sectors; and Et denotes total employment in the country. We have six LQ variables for every regions for the six sectors: (1) agriculture; (2) energy and manufacturing; (3) construction; (4) distribution, transport and common services; (5) finance and other services; and vi) non-market services. The sectoral location quotients are calculated for every year in each region. They are labeled respectively as variables: ‘agriculture’, ‘industry’, ‘construction’, ‘trade and retail’, ‘finance’, ‘non-market sector’.

This includes EPEN voters for the years, before Chrysi Avgi evolved from EPEN and became founded as an official party.

The share of ND voters cannot be assumed directly inversely related to the share of other parties per se, as the number of parties in the different elections varies as well as the number of voting people and the fact that ND sometimes wins and sometimes loses the elections. What however can be reliably expected to be linearly captured by the share of the ND party in a locality, is a proxy for the particular right-minded-political culture in the locality.

To use an interaction term in this 2SLS setting, we first obtain the purged predicted value of ‘center-right (%)’from a 2SLS for model (2) without interaction term. Then, we multiply this purged value with ‘adj. budget deficit’ in order to obtained a cleaned from endogeneity interaction term between the economic and cultural triggers.

The variable ‘center-right (%)’ captures the standard pro-right orientation as opposed to the ultra-right orientation. With the center-right orientation, the radical right party shares the right ideology, but the ultra-right party is an extreme form of ideology and in this sense it might have similarity with extreme left parties. Disentangling which part of the ultra-right motivation is leading (its right orientation or its radical orientation) is important. If the economic shock causes an increase in the extreme votes, we will observe an increase in the share of votes for the ultra-right and ultra-left parties. If the austerity radicalizes only the right oriented voters, we will see an increase among the shares of center- and ultra-right voters, but not of the percentage of ultra-left voters. This clarifies the economic meaning and political ideological and attitudinal difference behind the reaction captured in the increase of the voting for the ultra-right party that we analyze here.

The relationship of this instrument with the left extreme party KKE is of course opposite in sign.

It is noteworthy that while Table 2a–d presents different quantifications and use different sets of controls, indifferent of measurement alternatives tried, the results obtained are always consistent and lead to a very similar economic interpretation.

As many countries, Greece experiences strong agglomeration around its capital city—Athens—and its corresponding NUTS3 region—Attika. Also some of the regions such as Crete, Peloponnese and Thessaly also group as an outstanding gear of development different from the rest of Greece (see for example Ioannides and Petrakos 2000) on these topics. Yet, the regional economic disparities and agglomerations regard the GVA (productivity levels) and population concentrated in the NUTS3. We do address these variables directly in our analysis, so basically the disparities between the units are very clearly quantified and their effects are reported. We don’t know why the NUTS 3 regions are having disparities, but we clearly learn how their disparities are associated with their radicalization under economic shocks and given their cultural heritage in political conservatism.

The results across all specifications with and without this last battery of controls are consistent. The use of the latter however reduces the number of observations because it is available for a shorter period of years. Thus, we present in Table 2 both types of results. The full list of tables of various tried specifications with diverse lists of controls is available upon request.

When we use the cultural trigger as a treatment we include in the matching also the economic trigger as an explanatory variable and the historic cultural variable in order to take away the endogeneity effect; when we use the economic trigger as a treatment, we use the cultural variable as a regressor in the matching model.

Tables with these descriptive statistics are available upon request.

References

Alesina A, Devleeschauwer A, Easterly W, Kurlat S, Wacziarg R (2002) Fractionalization. NBER working paper series, WP 9411

Andreadis I (2013) Voting advice applications: a successful nexus between informatics and political science. BCI’13, September 19–21 2013, Thessaloniki, Greece. http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2490257.2490263

Andreadis I (2015) Help me vote Hellenic parliamentary election 2015: the Greek voter 2015. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], Ann Arbor, MI, 2015-02-14. http://doi.org/10.3886/E29776V2

Bartlett J, Miller C (2012) The edge of violence: towards telling the difference between violent and non-violent radicalization. Terror Polit Violence 24(1):1–21

Baumeister C, Benati L (2013) Unconventional monetary policy and the Great Recession. Estimating the macroeconomic effects of a spread compression at the zero lower bound. Int J Cent Bank 9(2):165–212

Becker G (1968) Crime and punishment. J Polit Econ 76(2):196–217

Becker G (1975) Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis. Columbia University Press, New York

Becker S, Grosfeld I, Grosjean P, Voigtländer N, Zhuravskaya E (2018) Forced migration and human capital: evidence from post-WWII population transfers. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3173648 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3173648

Dharmapala D, Garoupa N, McAdams R (2009) Belief in a just world, blaming the victim, and hate crime statutes. Rev Law Econ 5:311–345

Feinstein C, Temin P, Toniolo G (2008) The world economy between the world wars. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ferrero M (2002) The political life cycle of extremist organizations. In: Breton A, Galeotti G, Salmon P, Wintrobe R (eds) Political extremism and rationality. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 155–182

Ferrero M (2005) Radicalization as a reaction to failure: an economic model of Islamic extremism. Public Choice 122(1/2):199–220

Fetzer T (2018) Did austerity cause Brexit? CESifo working paper no. 7159, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo), pp 1–37

Florence P (1939) Report of the location of industry, political and economic planning: London, UK

Galofre-Vila G, Meissner C, McKee M, Stuckler D (2017) Austerity and the rise of the Nazi party. NBER working paper no. 24106, pp 1–60

Glaeser E (2005) The political economy of hatred. Q J Econ 120(1):45–86

Hall E (1966) The hidden dimension. Doubleday, Garden City

Harmgart H, Huck S (2009) Dogville or an illustration of some properties of general equilibrium. Econ Voice 6(1):4

Herzog D (2015) On aggression: psychoanalysis as moral politics in post-Nazi Germany. EUI working paper MWPLS:2015/01

Hirschman A, Rothschild M (1973) Changing tolerance for income inequality development. Q J Econ 87(4):544–566

Hooghe L, Marks G, Wilson C (2002) Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comp Polit Stud 35(8):965–989

Ioannides YM, Petrakos G (2000) Regional disparities in Greece: the performance of Crete, Peloponnese and Thessaly. EIB Papers 5(1):30–58 (European Investment Bank (EIB), Luxembourg)

Jackson M (2011) An overview of social networks and economic applications. https://web.stanford.edu/~jacksonm/socialnetecon-chapter.pdf

Kapetanios G, Mumtaz H, Stevens I, Theodoridis K (2012) Assessing the economy wide effects of quantitative easing. Econ J 122(564):F316–F347

Kets W, Sandroni A (2016) A belief-based theory of homophily. Mimeo. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2871514 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2871514

Kuziemko I, Buell R, Reich T, Norton M (2014) Last-place aversion: evidence and redistributive implications. Q J Econ 129(1):105–149

Lamberson PJ, Page SE (2012) Tipping points. Q J Polit Sci 7:175–208

Los B, McCann P, Springford J, Thissen M (2017) The mismatch between local voting and the local economic consequences of Brexit. Reg Stud 51(5):786–799

Marx K (1844) Contribution t critique of Hegel’s philosophy of law: introduction. In Karl Marx and Frederick Engels Collected Works, vol III(1844):184–185

Mumtaz H, Theophiopoulou A (2017) The impact of monetary policy on inequality in the U.K. An empirical analysis. Eur Econ Rev 98:410–423

Myrdal G (1957) Rich lands and poor: the road to world prosperity. Harper and Bros, New York

Parsons CR, Winters LA (2014) International migration, trade and aid: a survey. International Migration Institute, University of Oxford, WP-90-2014

Pastor L, Veronesi P (2018) Inequality aversion, populism, and the backlash against globalization (December 21, 2018). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3224232 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3224232

Pérez T, Fernández-Gracia J, Ramasco J, Eguíluz V (2015) Persistence in voting behavior: stronghold dynamics in elections. In: International conference on social computing, behavioral-cultural modeling, and prediction SBP 2015: social computing, behavioral-cultural modeling, and prediction, pp 173–181

Piketty T (1995) Social mobility and redistributive politics. Q J Econ 110:551–583

Ravallion M, Lokshin M (2000) Who wants to redistribute? The tunnel effect in 1990s Russia. J Public Econ 76(1):87–104

Rodríguez-Pose A (2017) The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Camb J Reg Econ Soc 11(1):189–209

Romer P (1990) Endogenous technological change. J Polit Econ 98(5):71–102

Satyanath S, Voigtländer N, Voth H-J (2017) Bowling for fascism: social capital and the rise of the Nazi Party. J Polit Econ 125(2):478–526

Smith A (1759) The theory of moral sentiments. Printed for A. Millar, and A. Kincaid and J. Bell, London

Tubadji A (2012) Culture-based development: empirical evidence for Germany. Int J Soc Econ 39(9):690–703

Tubadji A (2013) Culture-based development: culture and institutions—economic development in the regions of Europe. Int J Soc Syst Sci 5(4):355–391

Tubadji A, Nijkamp P (2015) Cultural gravity effects among migrants: a comparative analysis of the EU15. Econ Geogr 91(3):344–380

Tubadji A, Nijkamp P (2016) Six degrees of cultural diversity and R&D output efficiency: cultural percolation of new ideas—an illustrative analysis of Europe. Lett Spat Resour Sci 9(3):247–264

Van Cott N (2007) Doomsters, evil I’s, and tunnel-vision economics. Indep Rev 11(4):595–599

Voigtländer N, Voth H (2012) Persecution perpetuated: the medieval origins of anti-semitic violence in Nazi Germany. Q J Econ 127(3):1339–1392

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Definition of variables

Model component | Variable name | Source | Definition | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Radicalization | Ultra-right (%) | State Database for National and European Elections-YPES.GR | % of voters from total voters in support of the ultra-right party (Chrysi Avgi) | 408 | 5.62 | 8.21 | 0 | 38.95 |

Change ultra-right (%) | State Database for National and European Elections-YPES.GR | difference between current and previous year % vote for the ultra-right party (Chrysi Avgi) | 408 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 | |

Ultra-left (%) | State Database for National and European Elections-YPES.GR | % of voters from total voters in support of the ultra-left party (Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas) | 357 | 5.92 | 3.27 | 1.11 | 24.69 | |

Center-right (%) | State Database for National and European Elections-YPES.GR | % of voters from total voters in support of the center-right party (Nea Dhimokratia) | 408 | 32.36 | 8.15 | 8.44 | 54.18 | |

SHOCK | Adj. budget deficit | EUROSTAT | Adjusted budget deficit as defined by EUROSTAT, i.e., the percentage change between actual and previously predicted based on extrapolation GDP for the region | 408 | − 6.26 | 4.15 | − 12.6 | − 1.5 |

Dummy adj. budget deficit | Generated | Dummy variable equal to 1 when the adjusted budget deficit value is higher than the mean value of this variable | 408 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | |

Austerity dummy (2010 after) | Generated | Dummy variable equal to 1 when the year is equal to or later than 2010 | 408 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | |

Culture (conservative attitudes) | Pro-monarchy 1974 (%) | Newspaper ‘Rizospastis’, Dec. 1974, National Library of Greece | % of voters from total voters in support of the referendum for monarchy which took place in 1974 (historic variable) | 408 | 34.42 | 10.19 | 5.90 | 59.52 |

Dummy pro-monarchy in 1974 | Newspaper ‘Rzospastis’, Dec. 1974, National Library of Greece | Dummy variable equal to 1 when the % vote for monarchy was above the mean for variable %vote_monarchy_referendum’74 | 408 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | |

Culturo-economic ‘Dogville Effect’ trigger | Interaction: ultra-right (%) and adj. budget deficit | Generated | Interaction between (i) a dummy = 1 when the ‘%vote_ultra_right (Chrysi Avgi)’ is above the mean percentage support for this party for the country and (ii) ‘adj_budget_deficit’ variables | 408 | − 2.29 | 3.29 | − 12.6 | 0 |

Interaction: purged ultra-right (%) and adj. budget deficit | Generated | We perched the value of ‘%vote_ultra_right (Chrysi Avgi)’ by using the instrument ‘%vote_monarchy_referendum’74’) and then we generated the same interaction as defined above, but using the perched value instead of the true value of ‘%vote_ultra_right (Chrysi Avgi)’ | 408 | − 4.73 | 4.67 | − 12.6 | 0 | |

Economic development (EconDev) | GVA | EUI regional dataset | Gross value added | 250 | 383.58 | 526.17 | 33.49 | 4756.74 |

lnGVA | Generated | Natural logarithm of gross value added (GVA) | 250 | 5.56 | 0.86 | 3.51 | 8.47 | |

Change lnGVA | Generated | difference between current and previous year ln_GVA | 200 | − 363.53 | 506.54 | − 4748.32 | − 29.85 | |

Decrease lnGVA | Generated | A dummy variable equal to 1 when ‘change ln_GVA’ < mean of ‘change ln_GVA’ | 200 | 655.00 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | |

Control variables | Employment | EUI regional dataset | Total number of employed people in the region | 250 | 56.15 | 66.30 | 4.08 | 528.32 |

Change employment | Generated | Difference between current and previous year values of ‘employment’ in the region | 200 | − 2862.55 | 143.39 | − 3028.6 | − 2304.02 | |

Total electorate | State Database for National and European Elections-YPES.GR | total number of electorate that voted | 408 | 182612.5 | 352337.4 | 1451 | 2,898,233 | |

Population | EUI regional dataset | total number of population in the region | 255 | 7062.24 | 177.18 | 6783.25 | 7225.45 | |

Sectoral location quotients | EUI regional dataset | |||||||

Agriculture | Generated | Dummy variable equal to 1 when the value of the employment localization quotient for the agricultural sector specialization in this region is higher than 1 | 250 | 1.161 | 0.59 | 0.15 | 2.51 | |

Construction | Generated | Dummy variable equal to 1 when the value of the employment localization quotient for the construction sector specialization in this region is higher than 1 | 250 | 1.114 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 3.80 | |

Finance | Generated | Dummy variable equal to 1 when the value of the employment localization quotient for the financial sector specialization in this region is higher than 1 | 250 | 0.913 | 0.48 | 0.24 | 4.57 | |

Industry | Generated | Dummy variable equal to 1 when the value of the employment localization quotient for the industry sector specialization in this region is higher than 1 | 250 | 0.902 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 2.67 | |

Non-market sector | Generated | Dummy variable equal to 1 when the value of the employment localization quotient for the non-market sector specialization in this region is higher than 1 | 250 | 0.999 | 0.23 | 0.46 | 1.91 | |

Trade and retail | Generated | Dummy variable equal to 1 when the value of the employment localization quotient for the trade and retail sector specialization in this region is higher than 1 | 250 | 0.918 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 2.19 | |

Change agriculture | Generated | Difference b/n the dummy variable for sector specialization in agriculture between current and previous year | 200 | 0.004 | 0.06 | − 0.18 | 0.21 | |

Change construction | Generated | Difference b/n the dummy variable for sector specialization in construction between current and previous year | 200 | 0.011 | 0.10 | − 0.28 | 0.43 | |

Change finance | Generated | Difference b/n the dummy variable for sector specialization in finance between current and previous year | 200 | − 0.001 | 0.06 | − 0.48 | 0.18 | |

Change industry | Generated | Difference b/n the dummy variable for sector specialization in industry between current and previous year | 200 | − 0.004 | 0.04 | − 0.22 | 0.12 | |

Change non-market sector | Generated | Difference b/n the dummy variable for sector specialization in non-market sector between current and previous year | 200 | 0.001 | 0.03 | − 0.14 | 0.07 | |

Change trade and retail | Generated | Difference b/n the dummy variable for sector specialization in trade between current and previous year | 200 | − 0.004 | 0.03 | − 0.11 | 0.08 |

Appendix 2: Economic shocks, cultural predisposition and the growth of radicalization

2.1 Estimation strategy

We use a propensity score matching and difference-in-differences combination of approaches to compare the effect from the economic and cultural triggers on the growth of the radical vote. Through the difference-in-differences method, we want to find out whether regions that have higher cultural predisposition (i.e., treated with the cultural trigger) suffer higher losses in terms of GVA. Alternatively, we use the same method to find out whether regions that have higher adjusted budget deficit (i.e., treated with the economic trigger) suffer higher losses in terms of GVA. Our matching procedure concerns ensuring that regions in our treated and control groups have comparable levels of local productivity. To ensure this we match the regions local productivity by the size of the local economy and sectoral local quotients.Footnote 16 We use alternative matching techniques to cross-check the reliability of our results. We try nearest neighbor matching, radius matching, Kernel matching, and stratified matching, as well as a simple t test and a regression with treatment and control variables.

Through the above procedures, we can gain some insights about two things. We can learn how different in economic performance the regions are when exposed to an economic shock. We learn how do regions perform over time in terms of radicalization when their cultural history is prone to right-wing preferences compared to regions whose past is not associated with such historic predisposition.

Next, this approach allows us to compare the effect of the economic crisis-related trigger and the historic pro-monarchy voting (i.e., the cultural trigger) on the growth in the percentage of voters for the Chrisy Avgi in the locality. If both triggers are found to be insignificant as treatment effects for local growth in ultra-right support, our H01 can be rejected.

Meanwhile, the matching procedure of this test informs us indirectly whether the ultra-right voting is itself associated with differences in regional economic development or not, which is the question of H02. This latter association, however, has some potential endogeneity to be dealt with more carefully.

Results

We looked separately at the cultural and economic triggers for radicalization, using each trigger as an alternative for defining the treatment effect in our matching and difference-in-differences (DiD) analysis.

The descriptive statistics show that after treating our regions with the two treatments, the treated and control groups result in a division between the regions in a ratio of about 60:40. We drop the observations for which there is no matching counterpart, and the years for which there is no information about the economic controls. Thus, we remain with a smaller number of observations. This dropping of the not well-matching observations, however, is required for a meaningful difference-in-differences causal exploration.Footnote 17

Table 4 presents our most important results from the test. Our DiD estimation shows whether the radicalization in the localities was higher when they were treated with a stronger economic shock or when they had a historic predisposition to right-wing preferences.

We are using here as a treatment: (1) a dummy variable indicating 1 for those regions above average pro-monarchy referendum voting behavior as a proxy for the cultural trigger as a treatment, or alternatively, (2) a dummy variable indicating experiencing above average adjusted budget deficit.

Our main results are as follows. The simple treatment tests, as well as our more sophisticated alternative matching methods used (i.e., nearest neighbor, Kernel matching, radius matching, and stratified matching), generate clearly consistent results per treatment. The two treatments—the cultural trigger and the economic trigger of radicalization—appear to have a completely different impact on the development of ultra-right preferences over time in Greek regions. As Table 4 shows, the effect from the adjusted budget deficit is associated with a strong explanatory power for the growth of ultra-right preferences; meanwhile, the development of the radicalization of a region has no clearly traceable relationship with the local cultural milieu described by the historic pro-monarchy voting. This result is always consistently obtained, indifferent of the matching procedure used. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that, while the ultra-right orientation is predictably more popular in places with a historically pro-right cultural milieu (as our preceding estimation has shown), the development of the radicalization over time is a purely economically triggered phenomenon.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tubadji, A., Nijkamp, P. Cultural attitudes, economic shocks and political radicalization. Ann Reg Sci 62, 529–562 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-019-00906-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-019-00906-1