Abstract

We examine the role that parental engagement with child’s education plays in the lifecourse dynamics of locus of control (LOC), one of the most widely studied non-cognitive skills related to economic decision-making. We focus on parental engagement as previous studies have shown that it is malleable, easy to measure, and often available for fathers, whose inputs are notably understudied in the received literature. We estimate a standard skill production function using rich British cohort data. Parental engagement is measured with information provided at age 10 by the teacher on whether the father or the mother is very interested in the child’s education. We deal with the potential endogeneity in parental engagement by employing an added-value model, using lagged measures of LOC as a proxy for innate endowments and unmeasured inputs. We find that fathers’, but not mothers’, engagement leads to internality, a belief associated with positive lifetime outcomes, in both young adulthood and middle age for female and socioeconomically disadvantaged cohort members. Fathers’ engagement also increases the probability of lifelong internality and fully protects against lifelong externality. Our findings highlight that fathers play a pivotal role in the skill production process over the lifecourse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A landmark study by Heckman et al. (2006) showed that a summary non-cognitive skill measure derived from self-efficacy and self-esteem personality questionnaires was at least as important as cognitive skills in determining a range of life outcomes including educational and labor market outcomes. A series of studies that followed and the role of non-cognitive skills in shaping lifetime opportunities were elegantly summarized in Almlund et al. (2011) and in Cobb-Clark (2015).

We have explored rigorously the possibility of alternative data to study this question. To date, the BCS1970 is the only available data set that provides LOC data in both childhood and at least some consistent LOC measurements in young adulthood and middle age. The National Child Development Study (NCDS) has data available on four adulthood LOC measures, but has no measures in childhood. The Avon cohort—the so-called ALSPAC study—provides LOC data in childhood, but the participants are only young adults in the follow-up. Our own previous research has exploited available LOC data to study the malleability of LOC in adolescence (over 8 years) and in adulthood (over 4 years) using the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey (Cobb-Clark and Schurer 2013; Elkins et al. 2017).

They argue that a reversed trend occurs because the youngest sample members (age 14) were lowest in internality in the first measurement period and therefore able to experience the largest increase.

The findings in Specht et al. (2013) may be driven by the utilization of LOC measures that were differently coded in the two measurement periods. Thus, changes in LOC may be the result of coding differences and not of differences in personality change.

Early work in the 1970s found that a socioeconomic gradient in internal control beliefs already existed among young school children (see Stephens and Delys (1973) for a review of this literature). Stephens and Delys (1973) found that pre-kindergarteners from disadvantaged backgrounds attending Head Start schools were more likely to report external control tendencies than middle class children from Montessori and cooperative nursery schools. In contrast, Bartel (1971) found that control perceptions did not differ between socioeconomic groups before entering first grade, but reported that substantial differences emerged by the sixth grade, an effect they suggest is driven by differences in the social control exerted by schools.

These findings are in line with previous studies suggesting that highly educated parents do not only spend more time with their children but spend their time on activities believed to be more productive or “developmentally effective” (Kalil et al. 2012).

Hofferth (2006) discusses the evidence on the positive association of non-traditional family structures—families that are not composed of married-biological-parents—and children’s behavior problems.

Note: The full CARALOC questionnaire contains 20 items, with five “distractors”. We have retained distractor item 12 based on a factor analysis because it improves the scale’s Cronbach’s alpha (see Ogollah, 2010).

Practically, such a large dimension is not possible, especially if a third predictor variable is added. To aid the data reduction process, the algorithm needs to categorise the continuous variables such as age 10 LOC. We ex ante specify to categorize age 10 LOC into three terciles. As we will demonstrate in the empirical section, the key conclusions of the analysis are not sensitive to this split.

Practically, the algorithm does this by including only levels of the predictor variable that are significantly different from each other. To reduce the b × a table to the most significant k × a with k = 2(1)b. Then choose the k × a table that has the most significant chi-squared statistic. The null hypothesis of the independence of the predictor variable age 10 LOC and the dependent variable age 42 is tested using the Pearson’s chi-square statistic. We use the—chaid—program for STATA written by Joseph N. Luchman at Behavioral Statistics Lead. The algorithm considers three steps: preparing predictors, merging categories, and selecting the split variable.

Cluster analysis is another data reduction technique which is designed to group similar observations in a data set, such that observations in the same group are as similar to each other as possible, and similarly, observations in different groups are as different to each other as possible. The “K-means” cluster analysis method groups observations by minimizing Euclidean distances between them. Euclidean distances are similar to measuring the hypotenuse of a triangle, where the differences between two observations on two variables, let’s say age 42 LOC and age 10 LOC, are plugged into the Pythagorean equation to solve for the shortest distance between the two points. This approach requires that all variables used to determine clustering using k-means must be continuous, which we will assume in our data setting. In order to perform k-means clustering, the algorithm randomly assigns k initial centers, a number which needs to be chosen by the user ex ante. We use the standard algorithm, the Hartigan-Wong algorithm, which aims to minimize the Euclidean distances of all points with their nearest cluster centers, by minimizing within-cluster sum of squared errors (SSE). K-means clustering also requires a priori specification of the number of clusters k, a choice that can be facilitated empirically with the data. We use a screeplot to graph within-group SSE against each cluster solution (Aldenderfer and Blashfield 1984).

When categorizing age 10 LOC ex ante into four quartiles or five quintiles, we obtain nine maturation pathway types. These are almost identical to the eight types described above, but we are able to identify a slightly more nuanced maturation profile (Fig. 7, Supplement).

A supplement, Table 4 reports the underlying sample numbers

Examples of items include “children should not be allowed to talk at the meal table”, “unquestioning obedience is not a good thing in a young child”, and “a well-brought up child is one who does not have to be told twice to do something.”

Optimally, we would like to use the same control variables for fathers and mothers. However, we rely on information about the father as reported by the mother in the interview. Father and mother roles in the family were very different in the 1970s and 1980s; therefore, work- and occupation-related information for mothers is less predictive in our models than for fathers. We have experimented with different specifications, among others specifications where we perfectly align the available control variables for fathers and mothers. Our estimation results and conclusions are not sensitive to the concern that paternal and maternal control variables are not perfectly symmetric.

In a further robustness check, we add also age 10 cognitive skills for children to further control for the possibility that parental engagement at age 10 reflects only unobserved skills.

For an overview of these standard models and how to calculate marginal probability effects, see Cameron and Trivedi (2005).

Our conclusions are robust to adding additional control variables for unobserved abilities at age 10. Parental engagement with the education of the child at age 10 could be the result of cognition difficulties that were not present at age 5, which caused especially fathers to engage with the child’s schooling. We added cognitive ability tests scores from age 10 into model (4) such as the BAS Word Definitions test BAS Recall of Digits test, BAS Similarities test, BAS Matrices test. The MPE for father’s interest in the child changes from 0.036 to 0.035 and remains statistically significant at the 5% level. These results are provided upon request.

For children where both parents were interested in their education, the MPEs for both father’s and mother’s interest are, respectively, .056 with a standard error of .016 (significant at the 1% level) and .019 with a standard error of .036 (not significant).

This calculation is based on a MPE of 4%-points and a base probability of 4%, which yields a percent decrease of 100.

This calculation is based on a MPE of 5%-points and a base probability of 25%, which yields a percent increase of 25.

References

Ahlin EM, Lobo Antunes MJ (2015) Locus of control orientation: Parents, peers, and place. J Youth Adolesc 44:1803–1818

Aldenderfer M, Blashfield R (1984) Cluster analysis sage publications. Newbury Park, California

Almlund M, Lee Duckworth A, Heckman J, Kautz T (2011) Personality psychology and economics. In: Eric SM, Hanushek A, Woessmann L (eds) Handbook of the economics of education, vol 4. pp 1–181

Andrisani P (1977) Internal-external attitudes, personal initiative, and the labor market experience of white and black men. J Human Res 12:308–328

Andrisani P (1981) Internal-external attitudes, sense of efficacy, and labor market experience: A reply to Duncan and Morgan. J Human Res 16:658–666

Bain HC, Boersma FJ, Chapman JW (1983) Academic achievement and locus of control in father-absent elementary school children. Sch Psychol Int 4:69–78

Bartel NR (1971) Locus of control and achievement in middle- and lower-class children. Child Dev 42:1099–1107

Biggs D, de Ville B, Suen E (1991) A method of choosing multiway partitions for classification and decision trees. J Appl Stat 18:49–62

Black N, Kassenboehmer S (2017) Getting weighed down: The effect of childhood obesity on the development of socioemotional skills. J Hum Cap 11:263–295

Bono ED, Francesconi M, Kelly Y, Sacker A (2016) Early maternal time investment and early child outcomes. Econ J 126:F96–F135

Bratti M (2007) Parents’ income and children’s school drop-out at 16 in england and wales: Evidence from the 1970 British Cohort Study. Rev Econ Household 5:15–40

Buddelmeyer H, Powdthavee N (2016) Can having internal locus of control insure against negative shocks? psychological evidence from panel data. J Econ Behav Org 122:88–109

Cabrera N, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bradley RH, Hofferth S, Lamb ME (2000) Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Dev 71:127–136

Caliendo M, Cobb-Clark D, Uhlendorff A (2015) Locus of control and job search strategies. Rev Econ Stat 97:88–103

Cameron A, Trivedi P (2005) Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. New York

Carton J, Nowicki S (1994) Antecedents of individual differences in locus of control of reinforcement-A critical review. Genet Soc Gen Psychol 120:31–81

Carton JS, Carton EER (1998) Nonverbal maternal warmth and children’s locus of control of reinforcement. J Nonverbal Behav 22:77–86

Carton JS, Nowicki S, Balser GM (1996) An observational study of antecedents of locus of control of reinforcement. Int J Behav Dev 19:161–175

Carton J, Nowicki S Jr (1996) Origins of generalized control expectancies: Reported child stress and observed maternal control and warmth. J Soc Psychol 136:753–760

Cha GW, Kim YC, Moon HJ, Hong WH (2017) New approach for forecasting demolition waste generation using chisquared automatic interaction detection (CHAID) method. J Clean Prod 168:375–385

Chamberlain G (1975) British births 1970. London

Chiteji N (2010) Time preference, noncognitive skills and well being across the life course: Do noncognitive skills encourage healthy behavior? Am Econ Rev Papers Proc 100:200–204

Cobb-Clark D, Kassenboehmer S, Schurer S (2014) Healthy habits: What explains the connection between diet, exercise, and locus of control? J Econ Behav Org 98:1–28

Cobb-Clark D, Schurer S (2013) Two economists’ musings on the stability of locus of control. Econ J 123:F358–F400

Cobb-Clark DA (2015) Locus of control and the labor market. IZA J Labor Econ 4:3

Cobb-Clark DA, Kassenboehmer S, Sinning M (2016) Locus of control and savings. J Banking and Fin 73:113–130

Cobb-Clark DA, Salamanca N, Zhu A (2019) Parenting style as an investment in human development. J Popul Econ 31:1315–1352

Coleman M, Deleire T (2003) An economic model of locus of control and the human capital investment decision. J Human Res 38:701–721

Conger R, Elder J Jr (1994) Families in troubled times. Aldine de Gruyter, New York

Crandall VC, Crandall BW (1983) Maternal and childhood behaviors as antecedents of internal-external control perceptions in young adulthood. In: Lefcourt HM (ed) Research with the locus of control construct: Developments and social problems. New York

Cunha F, Heckman JJ (2008) Formulating, identifying and estimating the technology of cognitive and noncognitive skill formation. J Human Res 43:738–782

Cunha F, Heckman JJ, Schennach SM (2010) Estimating the technology of cognitive and noncognitive skill formation. Econometrica 78:883–931

Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A (2010) Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. J Health Econ 29:1–28

Doherty M, Garfein R, Monterroso E, Brown D, Vlahov D (2000) Correlates of HIV infection among young adult short-term injection drug users. AIDS 14:717–726

Doherty WJ, Baldwin C (1985) Shifts and stability in locus of control during the 1970s: Divergence of the sexes. J Pers Soc Psychol 48:1048–1053

Dohmen T, Falk A, Golsteyn B, Huffman D, Sunde U (2017) Risk attitudes across the life course. Econ J 127:F95–F116

Duke MP Jr, Lancaster WL (1976) A note on locus of control as a function of father absence. J Gen Psychol 129:335–336

Duncan GJ, Magnuson K, Votruba-Drzal E (2017) Moving beyond correlations in assessing the consequences of poverty. Annu Rev Psychol 68:413–434

Duncan G, Morgan J (1981) Sense of efficacy and changes in economic status - A comment on Andrisani. J Human Res 16:649–657

Elkins RK, Kassenboehmer SC, Schurer S (2017) The stability of personality traits in adolescence and young adulthood. J Econ Psychol 60:37–52

Evans G (2004) The environment of childhood poverty. Am Psychol 59:77–92

Evans G, English K (2002) The environment of poverty: Multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Dev 73:1238–1248

Evans G, Kim P (2010) Multiple risk exposure as a potential explanatory mechanism for the socioeconomic status-health gradient. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1186:174–189

Feinstein L, Robertson D, Symons J (1999) Pre-school education and attainment in the national child developement study and british cohort study. Educ Econ 7:209–234

Feinstein L, Symons J (1999) Attainment in secondary school. Oxf Econ Pap 51:300–321

Fiorini M, Keane MP (2014) How the allocation of children’s time affects cognitive and noncognitive development. J Labor Econ 32:787–36

Fishel M, Ramirez L (2005) Evidence-based parent involvement interventions with school-aged children. Sch Psychol Q 20:371–402

Fletcher J, Schurer S (2017) Origins of adulthood personality: The role of adverse childhood experiences. B.E. Journal of Economic Analsys & Policy 17

Flouri E (2006) Parental interest in children’s education, children’s self-esteem and locus of control, and later educational attainment: Twenty-six year follow-up of the 1970 British Birth Cohort. Br J Educ Psychol 76:41–55

Flouri E, Buchanan A (2003) The role of father involvement in children’s later mental health. J Adolesc 26:63–78

Flouri E, Buchanan A (2004) Early father’s and mother’s involvement and child’s later educational outcomes. Br J Educ Psychol 74:141–153

Flouri E, Hawkes D (2008) Ambitious mothers-successful daughters: Mothers’ early expectations for children’s education and children’s earnings and sense of control in adult life. Br J Edu Psychol 78:411–433

Furnham A, Steele H (1993) Measuring locus of control: A critique of general, children’s, health-and work-related locus of control questionnaires. Br J Psychol 84:443–479

Gammage P (1975) Socialisation, schooling and locus of control. Bristol

Garner B, Godley S, Rodney R, Dennis M, Smith J, Godley M (2008) Exposure to adolescent community reinforcement approach treatment procedures as a mediator of the relationship between adolescent substance abuse treatment retention and outcome. J Subst Abuse Treat 36:252–264

Gerris JR, Dekovic M, Janssens JM (1997) The relationships between social class and childrearing behaviors: Parents’ perspective taking and value orientations. J Marriage Fam 59:834–847

Gershoff E, Aber J, Raver C, Lennon M (2007) Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Dev 78:70–95

Gonzalez-DeHass AR, Willems PP, Holbein MFD (2005) Examining the relationship between parental involvement and student motivation. Educ Psychol Rev 17:99–123

Gordon D, Nowicki S, Wichern F (1981) Observed maternal and child behaviors in a dependency producing task as a function of children’s locus of control orientation. Merrill-Palmer Q Behav Develop 27:43–51

Grolnick WS, Benjet C, Kurowski CO, Apostoleris NH (1997) Predictors of parent involvement in children’s schooling. J Educ Psychol 89:538–548

Grolnick WS, Slowiaczek ML (1994) Parents’ involvement in children’s schooling: A multidimensional conceptualization and motivational model. Child Dev 65:237–252

Hadsell L (2010) Achievement goals, locus of control, and academic success in economics. Am Econ Rev Paper Proc 100:272–276

Hammond C, Feinstein L (2005) The effects of adult learning on self-efficacy. Lond Rev Educ 3:265–287

Hart B, Risley T (1995) Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul Brookes, Baltimore

Hatch SL, Harvey SB, Maughan B (2010) A developmental-contextual approach to understanding mental health and well-being in early adulthood. Soc Sci Med 70:261–268

Heckman JJ (2008) Role of income and family influence on child outcomes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1136:307–323

Heckman JJ (2011) The american family in black and white: A post-racial strategy for improving skills to promote equality. Daedalus 140:70–89

Heckman J, Stixrud J, Urzua S (2006) The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. J Labor Econ 24:411–482

Heineck G, Anger S (2010) The returns to cognitive abilities and personality traits in Germany. Labour Econ 17:535–546

Hertzman C, Power C, Matthews S, Manor O (2001) Using an interactive framework of society and lifecourse to explain self-rated health in early adulthood. Soc Sci Med 53:1575–1585

Hill NE, Taylor LC (2004) Parental school involvement and children’s academic achievement: Pragmatics and issues. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 13:161–164

Hill NE, Tyson DF (2009) Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Dev Psychol 45:740–763

Hofferth SL (2006) Residential father family type and child well-being: Investment versus selection. Demography 43:53–77

Hornby G, Lafaele R (2011) Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educ Rev 63:37–52

Huat See B, Gorard S (2015) The role of parents in young people’s education-a critical review of the causal evidence. Oxf Rev Educ 41:346

Izzo CV, Weissberg RP, Kasprow WJ, Fendrich M (1999) A longitudinal assessment of teacher perceptions of parent involvement in children’s education and school performance. Am J Community Psychol 27:817–839

Jeynes W (2012) A meta-analysis of the efficacy of different types of parental involvement programs for urban students. Urban Educ 47:706–742

Johnston D, Schurer S, Shields M (2013) Exploring the intergenerational persistence of mental health: Evidence from three generations. J Health Econ 32:1077–1089

Johnston D, Schurer S, Shields M (2014) Maternal gender role attitudes, human capital investment, and labour supply of sons and daughters. Oxf Econ Pap 66:631–659

Jokela M, Batty GD, Deary IJ, Gale CR, Kivimaaki M (2009) Low childhood iq and early adult mortality: The role of explanatory factors in the 1958 british birth cohort. Pediatrics 124:e380–e388

Kaiser T, Li J, Pollmann-Schult M, Song AY (2017) Poverty and child behavioral problems: The mediating role of parenting and parental well-being. Int J Environ Res und Publ Health 14:E981

Kalil A, Mogstad M, Rege M, Votruba M (2016) Father presence and the intergenerational transmission of educational attainment. J Human Res 51:869–899

Kalil A, Ryan R, Corey M (2012) Diverging destinies: Maternal education and the developmental gradient in time with children. Demography 49:1361–1383

Kass GV (1980) An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data. Appl Stat 29:119–127

Kassenboehmer S, Leung F, Schurer S (2018) University education and non-cognitive skill development. Oxf Econ Pap 70:538–562

Katkovsky W, Crandall VC, Good S (1967) Parental antecedents of children’s beliefs in internal-external control of reinforcements in intellectual achievement situations. Child Dev 38:765–776

Kautz T, Heckman J, ter Weel B, Borghans L (2014) Fostering and measuring skills - improving cognitive and non-cognitive skills to promote lifetime success. OECD Education Working Papers 110, OECD Publishing

Kiernan K, Mensah F (2011) Poverty, family resources and children’s early educational attainment: the mediating role of parenting. Br Educ Res J 37:317–336

Kohl GO, Lengua LJ, McMahon RJ (2000) Parent involvement in school conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. J Sch Psychol 38:501–523

Kohn M (1969) Class and conformity: A study in values. Chicago

Lachman M (2006) Perceived control over aging-related declines: Adaptive beliefs and behaviors. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 15:282–286

Lachman M, Leff R (1989) Perceived control and intellectual functioning in the elderly: A 5-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychol 25:722–728

Lancaster WW, Richmond BO (1983) Perceived locus of control as a function of father absence, age, and geographic location. J Genet Psychol 143:51–56

Lekfuangfu WN, Cornaglia F, Powdthavee N, Warrinnier N (2017) Locus of control and its intergenerational implications for early childhood skill formation. Econ J Forthcoming

Lewis SK, Ross CE, Mirowsky J (1999) Establishing a sense of personal control in the transition to adulthood. Soc Forces 77:1573–1599

Lynch S, Hurford DP, Cole A (2002) Parental enabling attitudes and locus of control of at-risk and honors students. Adolescence 37:527–549

Macdonald AP (1971) Internal-external locus of control: Parental antecedents. J Consult Clin Psychol 37:141–147

Magnusson K, Duncan G (2002) Parents in poverty. In: Bornstein MH (ed) Handbook of parenting. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp 95–121

Mattingly DJ, Prislin R, McKenzie TL, Rodriguez JL, Kayzar B (2002) Evaluating evaluations: The case of parent involvement programs. Rev Educ Res 72:549–576

McClun L, Merrell KW (1998) Relationship of perceived parenting styles, locus of control orientation, and self-concept among junior high age students. Psychol Sch 35:381–390

McGee A (2015) How the perception of control influences unemployed job search. Ind Labor Relat Rev 68:184–211

McLoyd V (1994) Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol 53:185–204

MIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group (2012) Demographic and behavioural predictors of sexual risk in the NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial. AIDS 11:S21–S27

Mirowski J (1995) Age and the sense of control. Soc Psychol Q 58:31–43

Mirowsky J, Ross C (1998) Education, personal control, lifestyle and health: A human capital hypothesis? Res Aging 20:415–449

Mirowsky J, Ross C (2007) Life course trajectories of perceived control and their relationship to education. Am J Soc 112:1339–1382

Moilanen KL, Shen YL (2014) Mastery in middle adolescence: The contributions of socioeconomic status, maternal mastery and supportive-involved mothering. J Youth Adolesc 43:298–310

Mostafa T, Wiggins RD (2015) The impact of attrition and non-response in birth cohort studies: a need to incorporate missingness strategies. Longitud Life Course Stud 6:131–146

Murphy EL, Comiskey CM (2013) Using CHI-squared automatic interaction detection (CHAID) modelling to identify groups of methadone treatment clients experiencing significantly poorer treatment outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat 45:343–349

Nowicki S, Strickland B (1973) A locus of control scale for children. J Consult Clin Psychol 40:148–154

Osborn AF (1990) Resilient children: A longitudinal study of high achieving socially disadvantaged children. Early Child Development and Care 62:23–47

Peruzzi A (2014) Understanding social exclusion from a longitudinal perspective : A capability-based approach. J Human Develop Capabilities 15:335–354

Power C, Pereira S, Li L (2015) Childhood maltreatment and BMI trajectories to mid-adult life: follow-up to age 50y in a british birth cohort. PLoS One 10:e0119985

Quinlan J (1993) Programs for machine learning. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc, San Francisco

Ratner B (2003) Statistical modeling and analysis for database marketing effective techniques for mining big data. Chapman and Hall/CRC, Boca Raton (Florida)

Reynolds AJ (1992) Comparing measures of parental involvement and their effects on academic achievement. Early Child Res Q 7:441–462

Reynolds AJ, Weissberg RP, Kasprow WJ (1992) Prediction of early social and academic adjustment of children from the inner city. Am J Community Psychol 20:599–624

Ritschard G (2010) CHAID and earlier supervised tree methods. Tech rep., Institute for demographic and life course science, University of Geneva

Ross CE, Broh BA (2000) The roles of self-esteem and the sense of personal control in the academic achievement process. Sociol Educ 73:270–284

Ross C, Mirowsky J (2002) Age and the gender gap in the sense of personal control. Soc Psychol Q 65:125–145

Rotter J (1966) Generalized expectancies of internal versus external control of reinforcements. Psychol Monogr 80:1–28

Rutter M, Tizard J, Whitmore K (1970) Education health and behaviour. Longman, Harlow

Sarkadi A, Kristiansson R, Oberklaid F, Bremberg S (2008) Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatr 97:153–158

Schnitzlein DD, Stephani J (2016) Locus of control and low-wage mobility. J Econ Psychol 53:164–177

Schoon I, Parsons S, Sacker A (2004) Socioeconomic adversity, educational resilience, and subsequent levels of adult adaptation. J Adolesc Res 19:383–404

Schurer S (2015) Lifecycle patterns in the socioeconomic gradient of risk preferences. J Econ Behav Org 119:482–495

Schurer S (2017a) Does education strengthen life skills of adolescents? IZA World of Labor 366

Schurer S (2017b) Bouncing back from health shocks: Locus of control and labor supply. J Econ Behav Org 133:1–20 1246

Specht J, Egloff B, Schmukle SC (2013) Everything under control? The effects of age, gender, and education on trajectories of perceived control in a nationally representative german sample. Dev Psychol 49:353–364

Spokas M, Heimberg RG (2008) Overprotective parenting, social anxiety, and external locus of control: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships. Cogn Ther Res 33:543

Stephens MW, Delys P (1973) External control expectancies among disadvantaged children at preschool age. Child Dev 44:670–674

Taris TW, Bok IA (1997) Effects of parenting style upon psychological well-being of young adults: Exploring the relations among parental care, locus of control and depression. Early Child Develop Care 132:93–104

Thomas C, Hypponen E, Power C (2008) Obesity and type 2 diabetes risk in mid adult life: the role of childhood adversity. Pediatrics 121:e1240–e1249

Todd P, Wolpin KI (2003) On the specification and estimation of the production function for cognitive achievement. Econ J 113:F3–F331

Ture M, Tokatli F, Kurt I (2009) Using Kaplan-Meier analysis together with decision tree methods (C&RT, CHAID, QUEST, C4.5 and ID3) in determining recurrence-free survival of breast cancer patients. Expert Syst Appl 36:2017–2026

Van Diepen M, Franses P (2006) Evaluating chi-square automatic interaction detection. Inf Syst 31:814–813

Weisz J, Stipek D (1982) Competence contingency, and the development of perceived control. Hum Dev 25:250–281

Westerlund H, Gustafsson PE, Theorell T, Janlert U, Hammarström A (2013) Parental academic involvement in adolescence, academic achievement over the life course and allostatic load in middle age: A prospective population-based cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 67:508–513

Westerlund H, Rajaleid K, Virtanen P, Gustafsson PE, Nummi T, Hammarström A (2015) Parental academic involvement in adolescence as predictor of mental health trajectories over the life course: A prospective population-based cohort study. BMC Publ Health 15:653

Whitbeck LB, Simons RL, Conger RD, Wickrama K, Ackley KA, Elder GH (1997) The effects of parents’ working conditions and family economic hardship on parenting behaviors and children’s self-efficacy. Soc Psychol Q 60:291–303

Wickline VB, Nowicki S, Kincheloe AR, Osborn AF (2011) A longitudinal investigation of the antecedents of locus of control orientation in children. i-Manager’s. J Educ Psychol 4:39

Wilder S (2014) Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: A meta-synthesis. Educ Rev 66:377–397

Williams E, Radin N (1999) Effects of father participation in child rearing: Twenty-year follow-up. Am J Orthopsychiatry 69:328–336

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank three anonymous referees and recognize their help and guidance in the review process. We also thank Deborah A. Cobb-Clark, Jana Mareckova, Michael A. Shields, David W. Johnston, and participants of the IZA/OECD/World Bank Workshop on Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Skills and Economic Development in Bertinoro, Italy, 3-4 October 2014 for valuable comments. We acknowledge financial support from an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Award (DE140100463) and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (project number CE140100027). All errors are our own.

Funding

Schurer acknowledges financial support from an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Award (DE140100463) and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (project number CE140100027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Junsen Zhang

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2 Robustness checks

2.1 2.1 Sample of cohort members who lived with their biological fathers

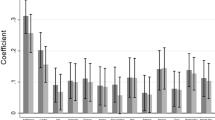

Relationship between parental interest in child’s education (mother, father) and the probability of a specific permanent control belief type (childhood-age30-age42). Reported are marginal probability effects obtained from a multinomial logit model estimated on 5465 observations with a full set of control variables. Types 7 and 8 have high lifelong internality; types 1 to 3 have lifelong externality; types 5 and 6 demonstrate a relative reversal whereby they are above-average in childhood but below-average in adulthood; and type 4 individuals exhibit the opposite pattern indicating low childhood internality and high adulthood internality. Types 4, 7, and 8 constitute 78% of the sample. Horizontal gray bars are 95% confidence intervals

2.2 2.2 Relaxing the number of percentiles in age 10 LOC to split the groups

2.3 2.3 Choice of number of clusters with k-mean clustering

2.4 2.4 k-mean clustering: ex ante five clusters

2.5 2.5 k-mean clustering: ex ante eight clusters

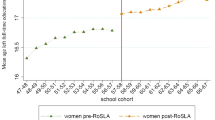

2.6 2.6 Heterogeneity: by sex

2.7 2.7 Heterogeneity: by socioeconomic status

Appendix 3 Determinants of age 10 locus of control beliefs

To understand the initial conditions of locus of control, we present in Table 7 estimation results from a regression model in which we regress a measure of age 10 internality on a set of standard early-life factors, including parental involvement in the education of the child. The dependent variable is a standardized version of our continuous childhood control belief measure, and parameter estimates are obtained using ordinary least squares (OLS). We allow for heteroskedastic standard errors (Huber-White). Results are presented by sex and socioeconomic status (according to father’s occupational class). High SES is defined as professional or manager occupations, while low SES is defined as low- or no-skilled or service occupational class. To reduce the high-dimensionality of estimation results, we present and limit our discussion to the estimated coefficients of interest. Full estimation results are provided upon request.

Parental interest in the education of the child predicts childhood internality independent of the influence of family structure; maternal, paternal, and individual childhood factors; and important socioeconomic indicators including parental occupational status and education. Overall, we find that children of parents very interested in their education are more internally oriented relative to children of parents who are not very interested. The magnitude of this association varies by sex and SES for mother’s involvement (standardized coefficients range between 0.07 and 0.15 SD and drop from significance among high SES cohort members), although the differences across groups are not statistically significant. In contrast, father’s involvement is a significant and stable predictor of internality across every group (standardized coefficients range between 0.17 and 0.22 SD), and the magnitude of this association with LOC is stronger than for mother’s involvement, especially for boys and children from privileged backgrounds. The estimates on father’s involvement are stronger in magnitude when focusing on families with biological or adoptee fathers (Panel B).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elkins, R., Schurer, S. Exploring the role of parental engagement in non-cognitive skill development over the lifecourse. J Popul Econ 33, 957–1004 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00767-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00767-5

Keywords

- Non-cognitive skills

- Locus of control

- Father school involvement

- Lifecourse dynamics

- British Cohort Study 1970