Abstract

This paper presents microevidence on the effect of adult longevity on schooling and fertility. Higher longevity is systematically associated with higher schooling and lower fertility. The paper looks at the 1996 Brazilian Demographic and Health Survey and constructs an adult longevity variable based on the mortality history of the respondent's family. Families with histories of high adult mortality in previous generations have systematically higher fertility and lower schooling. These effects are not associated with omitted variables and remain unchanged after a large array of factors is accounted for (demographic characteristics, family-specific child mortality, regional development, socioeconomic status, etc.).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Bleakley and Lange (2003) show that the eradication of hookworm disease in the American South was associated with increases in school attendance and literacy and reductions in fertility. Nevertheless, hookworm disease was in general associated with morbidity rather than mortality and seemed to have a direct effect on the costs of investments in human capital. Ram and Schultz (1979) analyze, in the case of India, the effects of health interventions on schooling and productivity, but it is also likely that morbidity was an important issue in this case. Our focus here is on the effects of longevity on the incentives to invest in human capital, from the perspective of its impacts on the horizon of productive life.

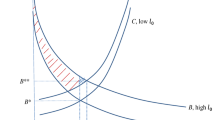

Note that these two potential effects are completely distinct: (1) as adult longevity increases, female schooling rises, increasing the opportunity cost of having children; and (2) as adult longevity increases, the returns to investments in children's human capital rises, increasing the investments in each child and the shadow price of number of children.

It is very difficult to interpret coefficients in an ordered probit model. A significant positive sign means that some mass is being shifted from very low realizations to very high ones, but in relation to intermediary outcomes it is impossible to make any general statement. In our case, it is easier to think it terms of the expected value of the outcome. In this sense, we can always say that a positive sign means a shift in the whole distribution to the right and an increase in the expected value of the outcome. Later on, when discussing the quantitative implications of the estimated coefficients, we calculate marginal effects on the expected value of the outcome.

For example, family wealth (grandparent's income) could determine parent's educational attainment and, as a result, reduce fertility, or determine access to contraceptive techniques.

The classifications of occupations available in the data set are the following: not working; professional, technical, or managerial; clerical; sales; agriculture self-employed; agriculture employee; household and domestic; services; skilled manual; and unskilled manual.

References

Barro RJ, Sala-i-Martin X (1995) Economic growth. McGraw-Hill, New York

Bergstrom TC (1996) Economics in a family way. J Econ Lit 34(4):1903–1934

Bils M, Klenow PJ (2000) Explaining differences in schooling across countries. Unpublished manuscript, University of Chicago

Blau DM, Robbins PK (1989) Fertility, employment, and child-care costs. Demography 26(2):287–299

Bleakley H, Lange F (2003) Chronic disease burden and the interaction of education, fertility and growth. Unpublished manuscript, University of Chicago

Cigno A (1998) Fertility decisions when infant survival is endogenous. J Popul Econ 11(1):21–28

Deaton A (1997) The analysis of household surveys—a microeconometric approach to development policy. World Bank and Oxford University Press, Washington, DC

Ehrlich I, Lui FT (1991) Intergenerational trade, longevity, and economic growth. J Polit Econ 99(5):1029–1059

Galor O, Weil DN (1999) From Malthusian stagnation to modern growth. Am Econ Rev 89(2):150–154

Hamermesh DS (1984) Life cycle effects on consumption and retirement. J Labor Econ 2(3):353–370

Hamermesh DS (1985) Expectations, life expectancy, and economic behavior. Q J Econ 100(2):389–408

Heckman JJ, Walker JR (1990) The relationship between wages and income and the timing and spacing of births: evidence from Swedish longitudinal data. Econometrica 58(6):1411–1441

Hurd MD, Mcgarry K (1997) The predictive validity of subjective probabilities of survival. NBER Working Paper 6193, Cambridge

Kalemli-Ozcan S (2001) Mortality decline and the quality–quantity trade-off: evidence from Africa. Unpublished manuscript, University of Houston

Kalemli-Ozcan S, Ryder HE, Weil DN (2000) Mortality decline, human capital investment, and economic growth. J Dev Econ 62(1):1–23

Lorentzen P, McMillan J, Wacziarg R (2004) Death and development. Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University

Meltzer D (1992) Mortality decline, the demographic transition, and economic growth. Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago, Department of Economics

Newman JL, Mcculloch CE (1984) A hazard rate approach to the timing of births. Econometrica 52(4):939–962

Ram R, Schultz TW (1979) Life span, health, savings, and productivity. Econ Dev Cult Change 27(3):399–421

Robson AJ (2001) The biological basis of economic behavior. J Econ Lit 39(1):11–33

Robson AJ (2003) A ‘bioeconomic’ view of the neolithic and recent demographic transitions. Unpublished manuscript, University of Western Ontario

Robson AJ, Kaplan HS (2003) The evolution of human life expectancy and intelligence in hunter–gatherer economies. Am Econ Rev 93(1):150–169

Rodriguez G, Cleland J (1988) Modelling marital fertility by age and duration: an empirical appraisal the page model. Popul Stud 42(2):241–257

Smith VK, Taylor DH Jr, Sloan FA (2001) Longevity expectations and death: can people predict their own demise? Am Econ Rev 91(4):1126–1134

Soares RR (2003) Fertility and schooling after the demographic transition. Unpublished manuscript, University of Maryland

Soares RR (2005) Mortality reductions, educational attainment, and fertility choice. Am Econ Rev 95(3):580–601

Tamura R (2001) Human capital and economic development. Unpublished manuscript, Clemson University

Zhang J, Zhang J, Lee R (2001) Mortality decline and long-run economic growth. J Public Econ 80(2):485–507

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper benefited from comments from Gary Becker; Roger Betancourt; Daniel Hamermesh; Steven Levitt; Kevin Murphy; Tomas Philipson; two anonymous referees; and seminar participants at the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, University of Chicago, University of Maryland-College Park, University of Texas-Austin, and LACEA 2002 (Madrid). Financial support from the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil) and the Esther and T.W. Schultz Endowment Fellowship (Department of Economics, University of Chicago) is gratefully acknowledged. The usual disclaimer applies.

Definition of variables

Definition of variables

Variable | Name | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

Number of children born | Children born | DHS | Number of children ever born to the respondent |

Number of children alive | Children alive | DHS | Number of children born to the respondent who are still alive |

Survival rate of adult siblings | Adult survival | DHS | Fraction of respondent's siblings that reached 10 who are still alive. Constructed from the mother's siblings' mortality history |

Survival rate of infant siblings | Child survival | DHS | Fraction of respondent's siblings born alive who reached 10. Constructed from the mother's siblings' mortality history |

Age | Age | DHS | Respondent's age in years |

Education | Educ | DHS | Respondent's education in single years of final educational attainment |

Religion | Christian | DHS | Respondent self-reported being from a Christian religion |

Religious attendance | Church | DHS | Respondent reported going once a week to a religious service |

Race | Black, mixed, Asian | DHS | Respondent's self-reported race (white and native South American are the missing categories) |

Urban residence | Urban | DHS | Whether place of residence where respondent was interviewed is urban |

Work | Work, self, unpaid | DHS | Whether respondent works, whether she is self-employed, and whether it is an unpaid job |

Occupation | Occup | DHS | Respondent's occupation, according to the following categories: not working; professional, technical, or managerial; clerical; sales; agriculture self-employed; agriculture employee; household and domestic; services; skilled manual; and unskilled manual |

Marriage history | Nevermar | DHS | Whether the respondent was never married |

Fecundity status | Infecund | DHS | Whether respondent is menopausal or sterile |

Number of siblings | Number siblings | DHS | Total number of respondent's siblings |

Electricity in house | Electric | DHS | Whether the household has electricity |

Water in house | Water | DHS | Whether major source of water for the household is piped water |

Toilet in house | Toilet | DHS | Whether the household has flush toilet |

Cars in house | Cars | DHS | Number of cars in the household |

State per capita GDP | GDP | IPEA Ministry of Planning, Brazil | State-specific per capita GDP in reais (1996) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soares, R.R. The effect of longevity on schooling and fertility: evidence from the Brazilian Demographic and Health Survey. J Popul Econ 19, 71–97 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0018-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0018-y