Abstract

Purpose

Paramedics are often the first healthcare contact for patients with infection and sepsis and may identify them earlier with improved knowledge of the clinical signs and symptoms that identify patients at higher risk.

Methods

A 1-year (April 2015 and March 2016) cohort of all adult patients transported by EMS in the province of Alberta, Canada, was linked to hospital administrative databases. The main outcomes were infection, or sepsis diagnosis among patients with infection, in the Emergency Department. We estimated the probability of these outcomes, conditional on signs and symptoms that are commonly available to paramedics.

Results

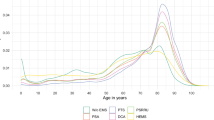

Among 131,745 patients transported by EMS, the prevalence of infection was 9.7% and sepsis was 2.1%. The in-hospital mortality rate for patients with sepsis was 28%. The majority (62%) of patients with infections were classified by one of three dispatch categories (“breathing problems,” “sick patient,” or “inter-facility transfer”), and the probability of infection diagnosis was 17–20% for patients within these categories. Patients with elevated temperature measurements had the highest probability for infection diagnosis, but altered Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), low blood pressure, or abnormal respiratory rate had the highest probability for sepsis diagnosis.

Conclusion

Dispatch categories and elevated temperature identify patients with higher probability of infection, but abnormal GCS, low blood pressure, and abnormal respiratory rate identify patients with infection who have a higher probability of sepsis. These characteristics may be considered by paramedics to identify higher-risk patients prior to arrival at the hospital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

30 June 2020

The original version of this article unfortunately contained a mistake.

References

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW et al (2016) The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 315:801–810. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0287

Seventienth World Health Assembly (2017) Improving the prevention, diagnosis and clinical management of sepsis, pp 1–4

Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W et al (2017) Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med 45:486–552. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255

Wang HE, Weaver MD, Shapiro NI, Yealy DM (2010) Opportunities for emergency medical services care of sepsis. Resuscitation 81:193–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.11.008

Groenewoudt M, Roest AA, Leijten FMM, Stassen PM (2014) Septic patients arriving with emergency medical services: a seriously ill population. Eur J Emerg Med 21:330–335. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000091

Gray A, Ward K, Lees F et al (2012) The epidemiology of adults with severe sepsis and septic shock in Scottish Emergency Departments. Emerg Med J 30:397–401. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2012-201361

Herlitz J, Bång A, Wireklint-Sundström B et al (2012) Suspicion and treatment of severe sepsis. An overview of the prehospital chain of care. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 20:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-20-42

Alberta Health Services (AHS) Emergency Medical Services (EMS) (2014) AHS medical control protocols (MCP). http://www.protocols.ahsems.com. Accessed 11 Sep 2015

Lane DJ, Blanchard IE, Cheskes S et al (2020) Strategy to identify paramedic transported sepsis cases in an Emergency Department Administrative Database. Prehosp Emerg Care 24:23–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2019.1611978

Jolley RJ, Quan H, Jetté N et al (2015) Validation and optimisation of an ICD-10-coded case definition for sepsis using administrative health data. BMJ Open 5:e009487–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009487

Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML et al (2016) Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 315:775–787. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0289

Harrell F (2015) Regression modeling strategies. With applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7

R Core Team (2016) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Yoshida K, Bartel A, Bohn J, Chipman JJ, McGowan LD, Barrett M, Christensen RHB, Gbouzill (2020) Tableone: create “Table 1” to describe baseline characteristics, version 0.11.1

Wasey JO (2017) ICD: tools for working with ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes, and finding comorbidities

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2007) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med 4:1623–1627. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A et al (2015) The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med 12:e1001885–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885

Seymour CW, Rea TD, Kahn JM et al (2012) Severe sepsis in pre-hospital emergency care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186:1264–1271. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201204-0713oc

Seymour CW, Cooke CR, Heckbert SR et al (2014) Prehospital intravenous access and fluid resuscitation in severe sepsis: an observational cohort study. Crit Care 18:533. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0533-x

Sterling SA, Miller WR, Pryor J et al (2015) The impact of timing of antibiotics on outcomes in severe sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis*. Crit Care Med 43:1907–1915. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001142

Sterling SA, Puskarich MA, Jones AE (2014) Prehospital treatment of sepsis: what really makes the “golden hour” golden? Crit Care 18:697. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0697-4

Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ et al (2016) Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 315:762–774. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0288

Lane DJ, Lin S, Scales DC (2019) Classification versus prediction of mortality risk using the SIRS and qSOFA scores in patients with infection transported by paramedics. Prehosp Emerg Care. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2019.1624901

Müller B, Becker KL, Schächinger H et al (2000) Calcitonin precursors are reliable markers of sepsis in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 28:977–983. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-200004000-00011

Trzeciak S, Dellinger RP, Chansky ME et al (2007) Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in patients with infection. Intensive Care Med 33:970–977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0563-9

Sierra R, Rello J, Bailén MAA et al (2004) C-reactive protein used as an early indicator of infection in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Intensive Care Med 30:2038–2045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-004-2434-y

Komorowski M (2020) Clinical management of sepsis can be improved by artificial intelligence: yes. Intensive Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05898-2

Wallgren UM, Castrén M, Svensson AEV, Kurland L (2014) Identification of adult septic patients in the prehospital setting. Eur J Emerg Med 21:260–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000084

Jouffroy R, Saade A, Ellouze S et al (2017) Prehospital triage of septic patients at the SAMU regulation: comparison of qSOFA, MRST, MEWS and PRESEP scores. Am J Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.10.030

Lane Daniel J, Hannah Wunsch, Refik Saskin, Sheldon Cheskes, Steve Lin, Morrison Laurie J, Scales Damon C (2020) Screening strategies to identify sepsis in the prehospital setting: a validation study. CMAJ 192(10):E230–E239. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190966

Coopersmith CM, De Backer D, Deutschman CS et al (2018) Surviving sepsis campaign: research priorities for sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med 44:1400–1426

Seymour CW, Kahn JM, Cooke CR et al (2010) Prediction of critical illness during out-of-hospital emergency care. JAMA 304:747–754. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1140

Royal College of Physicians (2015) National early warning score (NEWS). https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/national-early-warning-score-news. Accessed 28 Sep 2017

Lane DJ, Wunsch H, Saskin R et al (2019) Assessing severity of illness in patients transported to hospital by paramedics: external validation of 3 prognostic scores. Prehosp Emerg Care. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2019.1632998

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare related to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lane, D.J., Wunsch, H., Saskin, R. et al. Epidemiology and patient predictors of infection and sepsis in the prehospital setting. Intensive Care Med 46, 1394–1403 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06093-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06093-4