Abstract

Purpose

The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) study is typically interpreted as a trial of changes in neighborhood poverty. However, the program may have also increased exposure to housing discrimination. Few prior studies have tested whether interpersonal and institutional forms of discrimination may have offsetting effects on mental health, particularly using intervention designs.

Methods

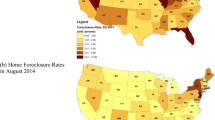

We evaluated the effects of MTO, which randomized public housing residents in 5 cities to rental vouchers, or to in-place controls (N = 4248, 1997–2002), which generated variation on neighborhood poverty (% of residents in poverty) and encounters with housing discrimination. Using instrumental variable analysis (IV), we derived two-stage least squares IV estimates of effects of neighborhood poverty and housing discrimination on adult psychological distress and major depressive disorder (MDD).

Results

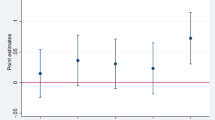

Randomization to voucher group vs. control simultaneously decreased neighborhood % poverty and increased exposure to housing discrimination. Higher neighborhood % poverty was associated with increased psychological distress [BIV = 0.36, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.03, 0.69] and MDD (BIV = 0.12, 95% CI − 0.005, 0.25). Effects of housing discrimination on mental health were harmful, but imprecise (distress BIV = 1.58, 95% CI − 0.83, 3.99; MDD BIV = 0.57, 95% CI − 0.43, 1.56). Because neighborhood poverty and housing discrimination had offsetting effects, omitting either mechanism from the IV model substantially biased the estimated effect of the other towards the null.

Conclusions

Neighborhood poverty mediated MTO treatment on adult mental health, suggesting that greater neighborhood poverty contributes to mental health problems. Yet housing discrimination-mental health findings were inconclusive. Effects of neighborhood poverty on health may be underestimated when failing to account for discrimination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- 2SLS:

-

Two-stage least squares

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ITT:

-

Intent-to-treat

- IV:

-

Instrumental variable

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- MTO:

-

Moving to Opportunity

References

Logan JR, Stults BJ (2011) The persistence of segregation in the metropolis: new findings from the 2010 census http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Data/Report/report2.pdf. Census Brief prepared for Project US2010. http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010. Brown University, Providence. Accessed 7 Oct 2011

Williams DR, Collins C (2001) Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep 116(5):404–416

Acevedo-Garcia D, Lochner KA, Osypuk TL, Subramanian SV (2003) Future directions in residential segregation and health research: a multilevel approach. Am J Public Health 93(2):215–221

Powell JA (2005) Dreaming of a self beyond whiteness and isolation. J Law Pol 18(13):13–45

Collins CA, Williams DR (1999) Segregation and mortality: the deadly effects of racism? Sociol Forum 14(3):495–523

Osypuk TL, Acevedo-Garcia D (2010) Beyond individual neighborhoods: a geography of opportunity perspective for understanding racial/ethnic health disparities. Health Place 16(6):1113–1123

Hunt M, Wise LA, Jipguep M-C, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L (2007) Neighborhood racial composition and perceptions of racial discrimination: evidence from the black women’s health study. Soc Psychol Q 70(3):272–289

Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, Williams DR (2015) Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 11(1):407–440. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728

Williams DR, Mohammed SA (2009) Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 32:20–47

Osypuk TL, Galea S, McArdle N, Acevedo-Garcia D (2009) Quantifying separate and unequal: racial-ethnic distributions of neighborhood poverty in metropolitan America. Urban Aff Rev 45(1):25–65

Oakes JM, Andrade KE, Biyoow IM, Cowan LT (2015) Twenty years of neighborhood effect research: an assessment. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2:80–87

Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Galea S (2008) Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health 62(11):940–946. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.066605

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T (2002) Assessing “neighborhood effects”: social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociol 28:443–478

Orr L, Feins JD, Jacob R, Beecroft E, Sanbonmatsu L, Katz LF, Liebman JB, Kling JR (2003) Moving to opportunity for fair housing demonstration program: interim impacts evaluation. US Dept of HUD, Washington, DC

Gennetian LA, Bos JM, Morris PA (2002) Using instrumental variables analysis to learn more from social policy experiments. MDRC Working papers on research methodology. Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation, New York

US Department of Housing & Urban Development (1996) Expanding housing choices for HUD-assisted families: moving to opportunity. First biennial report to congress, moving to opportunity for fair housing demonstration program

Goering J, Kraft J, Feins J, McInnis D, Holin MJ, Elhassan H (1999) Moving to opportunity for fair housing demonstration program: current status and initial findings. US Department of Housing & Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, Washington, DC

Kling JR, Liebman JB, Katz LF (2007) Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica 75(1):83–119

Kessler R, Andrews G, Colpe L, Hiripi E, Mroczek D, Normand S, Walters E, Zaslavsky A (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32(06):959–976

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, Wittchen H-U (1998) The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview short-form (CIDI-SF). Int J Methods Psychiatric Res 7(4):171–185

Rosenblum M, Van Der Laan MJ (2009) Using regression models to analyze randomized trials: asymptotically valid hypothesis tests despite incorrectly specified models. Biometrics 65(3):937–945

Davies NM, Smith GD, Windmeijer F, Martin RM (2013) Issues in the reporting and conduct of instrumental variable studies: a systematic review. Epidemiology 24(3):363–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828abafb

Staiger D, Stock JH (1997) Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica 65(3):557–586. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171753

Glymour MM (2006) Natural experiments and instrumental variable analyses in social epidemiology. In: Oakes JM, Kaufman JS (eds) Social epidemiology. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp 429–460

Morris PA, Gennetian LA, Duncan GJ (2005) Effects of welfare and employment policies on young children: new findings on policy experiments conducted in the early 1990s. Social Policy Report, Volume XIX, Number II

Bang H, Davis CE (2007) On estimating treatment effects under non-compliance in randomized clinical trials: are intent-to-treat or instrumental variables analyses perfect solutions? Stat Med 26(5):954–964. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2663

Hernán MA, Robins JM (2006) Instruments for causal inference—an epidemiologist’s dream? Epidemiology 17(4):360–372

Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB (1996) Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc 91(434):444–455

Glymour MM, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Robins JM (2012) Credible mendelian randomization studies: approaches for evaluating the instrumental variable assumptions. Am J Epidemiol 175(4):332–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr323

Swanson SA, Hernán MA (2013) Commentary: how to report instrumental variable analyses (suggestions welcome). Epidemiology 24(3):370–374. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828d0590

Baum CF, Schaffer ME, Stillman S (2007) Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/generalized method of moments estimation and testing. Stata J 7(4):465–506

Robins JM (1994) Correcting for non-compliance in randomized trials using structural nested mean models. Commun Stat 23:2379–2412

Nguyen QC, Osypuk TL, Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ (2015) Practical guidance for conducting mediation analysis with multiple mediators using inverse odds ratio weighting. Am J Epidemiol 181(5):349–356

Schmidt NM, Osypuk TL (2015) Why did a randomized program of housing mobility cause changes in the mental health of adolescents? The mediating role of substance use, social networks, and family mental health in the Moving to Opportunity Study. Paper presented at the Population Association of American 2015 Conference Paper, San Diego, CA.

Schmidt NM, Lincoln AK, Nguyen QC, Acevedo-Garcia D, Osypuk TL (2014) Examining mediators of housing mobility on adolescent asthma: results from a housing voucher experiment. Soc Sci Med 107(0):136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.020

Jones CP (2000) Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health 90(8):1212–1215

Acevedo-Garcia D, Rosenfeld LE, Hardy E, McArdle N, Osypuk TL (2013) Future directions in research on institutional and interpersonal discrimination and child health. Am J Public Health 103(10):1754–1763. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300986

World Health Organization (2014) Social determinants of mental health. Geneva Switzerland

Walker L, Verins I, Moodie R, Webster K (2005) Responding to the social and economic determinants of mental health. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, Moodie R (eds) Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice. World Health Organization, Geneva

Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR (1999) The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav 40(3):208–230

Clampet-Lundquist S, Edin K, Kling JR, Duncan GJ (2011) Moving teenagers out of high-risk neighborhoods: how girls fare better than boys. Am J Sociol 116(4):1154–1189. https://doi.org/10.1086/657352

Sciandra M, Sanbonmatsu L, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Ludwig J (2013) Long-term effects of the moving to opportunity residential mobility experiment on crime and delinquency. J Exp Criminol 9(4):451–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-013-9189-9

Yinger J (1995) Closed doors, opportunities lost: the continuing costs of housing discrimination. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Sampson RJ (2008) Moving to inequality: neighborhood effects and experiments meet social structure. Am J Sociol 114(1):189–231

Turner MA, Santos R, Levy DK, Wissoker D, Aranda C, Pitingolo R (2013) Housing discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities 2012. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, Washington, DC. https://www.huduser.gov/portal//Publications/pdf/HUD-514_HDS2012.pdf. Accessed 26 Aug 2015

Abravanel MD, Davis M, Company I (2006) Do we know more now? Trends in public knowledge, support, and use of fair housing law. US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research

Osypuk TL, Joshi P, Geronimo K, Acevedo-Garcia D (2014) Do social and economic policies influence health? A review. Curr Epidemiol Rep 1(3):149–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-014-0013-5

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (2015) United States fact sheet: federal rental assistance. National and state housing data fact sheets. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Washington, DC

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R21HD066312 and R21AA024530 (Dr. Osypuk, PI). The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Minnesota Population Center (P2C HD041023) funded through a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Neither NIH nor the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) had any role in the analysis or the preparation of this manuscript. HUD reviewed the manuscript to ensure respondent confidentiality was maintained in the presentation of results. The funders did not have any role in the conduct of the study or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TLO conceived the hypotheses, obtained the data, conducted the majority of the data analysis, and wrote the majority of the manuscript. MMG aided in writing the paper. MMG and EJTT advised on the statistical analysis and interpretation of findings, in addition to editing the methods. NMS and RDK analyzed the data, created tables, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osypuk, T.L., Schmidt, N.M., Kehm, R.D. et al. The price of admission: does moving to a low-poverty neighborhood increase discriminatory experiences and influence mental health?. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54, 181–190 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1592-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1592-0