Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

There is evidence for a bidirectional association between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Plasma β-amyloid (Aβ) is a potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. We aimed to investigate the association of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 with risk of type 2 diabetes.

Methods

We performed a case–control study and a nested case–control study within a prospective cohort study. In the case–control study, we included 1063 newly diagnosed individuals with type 2 diabetes and 1063 control participants matched by age (±3 years) and sex. In the nested case–control study, we included 121 individuals with incident type 2 diabetes and 242 matched control individuals. Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations were simultaneously measured with electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. Conditional logistic regression was used to evaluate the association of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations with the likelihood of type 2 diabetes.

Results

In the case–control study, the multivariable-adjusted ORs for type 2 diabetes, comparing the highest with the lowest quartile of plasma Aβ concentrations, were 1.97 (95% CI 1.46, 2.66) for plasma Aβ40 and 2.01 (95% CI 1.50, 2.69) for plasma Aβ42. Each 30 ng/l increment of plasma Aβ40 was associated with 28% (95% CI 15%, 43%) higher odds of type 2 diabetes, and each 5 ng/l increment of plasma Aβ42 was associated with 37% (95% CI 21%, 55%) higher odds of type 2 diabetes. Individuals in the highest tertile for both plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations had 2.96-fold greater odds of type 2 diabetes compared with those in the lowest tertile for both plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations. In the nested case–control study, the multivariable-adjusted ORs for type 2 diabetes for the highest vs the lowest quartile were 3.79 (95% CI 1.81, 7.94) for plasma Aβ40 and 2.88 (95% CI 1.44, 5.75) for plasma Aβ42. The multivariable-adjusted ORs for type 2 diabetes associated with each 30 ng/l increment in plasma Aβ40 and each 5 ng/l increment in plasma Aβ42 were 1.44 (95% CI 1.18, 1.74) and 1.47 (95% CI 1.15, 1.88), respectively.

Conclusions/interpretation

Our findings suggest positive associations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentration with risk of type 2 diabetes. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and explore the potential roles of plasma Aβ in linking type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease are both age-related diseases, with a steady increase in incidence and prevalence because of population ageing over the past 30 years [1]. Previous epidemiological studies have suggested a bidirectional association between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Individuals with diabetes have a 53% higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease than those without diabetes [2]. Compared with cognitively normal individuals, individuals with Alzheimer’s disease exhibit greater impairments in glucose and insulin metabolism [3,4,5]. The molecular mechanism underlying the relationship between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease remains unclear, although several shared pathophysiological features have been proposed for the two conditions [6], including insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress and protein misfolding. Since nearly 435 million people suffer from type 2 diabetes and 46 million people are living with dementia worldwide, and with the backdrop of an ageing society [7], understanding the relationship between these chronic diseases is of great importance.

β-Amyloid (Aβ), a 39–43 amino acid peptide derived from the enzymatic cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP), mainly consists of Aβ40 and Aβ42. In individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, Aβ is overproduced and excessively aggregates to form senile plaques in brain [8]. Based on the epidemiological association between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease, a large number of studies have explored the association of type 2 diabetes and amyloid pathologies in the human brain but found no significant association [9,10,11]. Notably, more than 40% of Aβ in the brain can be transported into peripheral blood [12, 13] and plasma Aβ has been used as a potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, in App and App/Ps1 transgenic mice (note that Ps1 is also known as Psen1), previous studies demonstrated that high plasma Aβ concentrations could induce impaired glucose and insulin tolerance [14, 15]. Peripheral insulin sensitivity was improved when the effect of plasma Aβ was neutralised by active immunisation with synthetic Aβ or passive immunisation with anti-Aβ-neutralising antibodies [15, 16]. Consistent with the results of animal studies, several epidemiological studies have indirectly indicated a potential positive association between plasma Aβ and type 2 diabetes. Plasma Aβ42 has been positively associated with BMI and fat mass [17], which are the major risk factors for type 2 diabetes. In addition, plasma Aβ autoantibody levels, which reflect plasma Aβ concentrations within a defined period, have been reported to be increased in individuals with type 2 diabetes [18]. However, only two cross-sectional studies have examined the differences in plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations between individuals with type 2 diabetes and those without diabetes; these yielded controversial results, probably because of the limited sample size in each study [14, 19].

Therefore, we investigated the association of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 with risk of type 2 diabetes in two independent studies: a large case–control study and a nested case–control study within a prospective cohort study.

Methods

Study design and population

We performed a large case–control study and a nested case–control study within a prospective cohort study. The case–control study consisted of 2126 participants, including 1063 individuals with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes and 1063 control participants with normal glucose tolerance (NGT). Newly diagnosed individuals with type 2 diabetes were consecutively recruited from the Department of Endocrinology, Tongji Medical College Hospital, Wuhan, China, between 2012 and 2015 (where they were diagnosed). Concomitantly, control participants were recruited from an unselected population undergoing a routine health check-up in the same hospital. One control participant was selected for each individual with type 2 diabetes, according to age (±3 years) and sex. Individuals meeting any of the following conditions were excluded from the study: age <30 years, age >80 years, BMI ≥40 kg/m2, history of diabetes mellitus, pharmacological treatment for hyperlipidaemia, any clinically systemic disease, any acute illness, chronic inflammatory disease or any infective disease.

To prospectively explore the association between plasma Aβ levels and risk of type 2 diabetes, we further conducted a nested case–control study within the ongoing longitudinal Tongji-Ezhou cohort (TJEZ). The TJEZ was initiated to investigate the association of lifestyle, dietary factors, and biochemical and genetic markers with chronic diseases in Ezhou, China. In brief, 5726 participants from Echeng Steel were recruited from 2013 to 2015, among whom 5533 (response rate, 96.6%) were enrolled for a baseline investigation. All participants included at baseline received healthcare in two medical centres (3101 retired employees at Echeng Steel hospital and 2432 working employees at Ezhou Center of Diseases Control and Prevention [Ezhou, China]). The first follow-up for retired employees was finished by the end of 2018, and the follow-up for working employees will be finished by mid-2020. During the follow-up, 156 new-onset type 2 diabetes cases were identified within retired employees according to fasting plasma glucose (FPG). Control participants were selected at random from individuals with normal fasting glucose among retired employees and matched to cases 2:1 by age (±3 years) and sex. The exclusion criteria were the same as the case–control study (see above); n = 4 individuals with type 2 diabetes aged >80 years were excluded. In addition, 28 cases without enough plasma and 3 cases with plasma Aβ concentrations below the detection limit were excluded. Finally, 121 individuals with new-onset type 2 diabetes and 242 well-matched control participants were included in the analysis of the nested case–control study.

All participants enrolled in the two studies were of Chinese Han ethnicity. Both studies were approved by the Ethics and Human Subject Committee of Tongji Medical College and all enrolled participants provided informed written consent.

Assessment of type 2 diabetes

In the case–control study, type 2 diabetes was diagnosed in accordance with the diagnostic criteria recommended by WHO in 1999 [20]: FPG ≥7.0 mmol/l and/or 2 h post-glucose load ≥11.1 mmol/l. NGT was considered as FPG <6.1 mmol/l and 2 h post-glucose load <7.8 mmol/l. In the TJEZ study, new-onset type 2 diabetes was confirmed as FPG ≥7.0 mmol/l.

Measurement of plasma Aβ concentrations

Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations were simultaneously measured in stored plasma. Plasma samples were divided into aliquots in polypropylene tubes, stored at −80°C and subsequently thawed on ice before plasma Aβ quantification. By using validated assay platforms from Meso Scale Discovery (MSD; Rockville, MD, USA), plasma Aβ concentrations were measured in the Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Environment and Health at the School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science &Technology (Wuhan, China). The detection limits of this assay were 20.0 ng/l for Aβ40 and 2.5 ng/l for Aβ42. The mean interassay coefficients of variation were 1.24% for Aβ40 and 6.31% for Aβ42, and the mean within-assay coefficients of variation were 6.67% for Aβ40 and 6.37% for Aβ42. All of the investigators were blinded to type 2 diabetes status.

Assessment of covariates

Baseline characteristics were obtained from semi-structured questionnaires, in which participants were required to provide information on their age, sex, height, weight, current smoking status, current alcohol drinking status, amount of physical activity, family history of diabetes and history of hypertension. BMI was calculated as weight divided by the square of height (kg/m2). Overnight fasting plasma samples were used to determine FPG, fasting plasma insulin (FPI), triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) and HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C). All participants in the case-control study also underwent an OGTT by taking 75 g of glucose orally, and venous blood samples were collected at 2 h for determination of 2 h post-glucose load values. HOMA-IR score was computed according to the equation: FPG (mmol/l) × FPI (pmol/l) ÷ 156.3.

Statistical analysis

General characteristics were summarised as mean (SD) for parametrically distributed data, median (interquartile range [IQR]) for nonparametrically distributed data and n(%) for categorical data. The differences in plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 and demographic and clinical characteristics between individuals with and without diabetes were evaluated with the use of Student’s t test (parametric distribution) or Mann–Whitney U test (nonparametric distribution) for continuous variables, and χ2 test for categorical variables. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were estimated to assess correlations between plasma Aβ40, plasma Aβ42 and metabolic parameters (FPG, FPI, HOMA-IR, triacylglycerol, total cholesterol, LDL-C and HDL-C). Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate ORs (95% CIs) for type 2 diabetes by quartiles of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42, with cut-offs defined by the distributions of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations among control participants. Tests for linear trend were conducted by assigning the median value for each quartile and defining it as a continuous variable in binary logistic regression analyses. We also calculated the ORs (95% CIs) for type 2 diabetes associated with each 30 ng/l increment in plasma Aβ40 and each 5 ng/l increment in plasma Aβ42. We adjusted for several potential confounders in multivariable models, including age (≤40, 41–50, 51–60 or ≥61 years in the case–control study; ≤60, 61–65, 66–70 or ≥71 years in the nested case–control study), sex (male or female), BMI (<18.5, 18.5–<24, 24–<28, or ≥28 kg/m2), current smoking status (no or yes), current drinking status (no or yes), physical activity (no or yes), family history of diabetes (no or yes) and hypertension (no or yes). We further performed stratified analyses of associations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations with type 2 diabetes by age (≤50 or >50 years in the case–control study; ≤65 or >65 years in the nested case–control study), sex, BMI (<24 or ≥24 kg/m2), current smoking status, current drinking status, physical activity, family history of diabetes and hypertension, followed by interaction tests with multiplicative terms performed to determine interactions between plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 (as continuous variables) and these stratification variables (as categorical variables). In addition, we explored the joint association of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 with type 2 diabetes by tertiles of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations. Tests for interaction between plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 were conducted by adding a multiplicative term (both plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 as continuous variables) into the multivariate logistic regression model.

All of the data analyses were performed with SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and Stata/SE 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The p values presented were two-tailed and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Case–control study with a cross-sectional design

Characteristics of participants

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 2126 participants in the case–control study are shown in Table 1. Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations were significantly higher in individuals with type 2 diabetes compared with the control participants. As expected, individuals with type 2 diabetes had higher BMI and higher levels of FPG, FPI, triacylglycerols and LDL-C compared with individuals in the control group. They also had higher HOMA-IR, and lower HDL-C levels. Prevalence of family history of diabetes and hypertension were greater among individuals with diabetes. In addition, plasma Aβ40 moderately correlated with plasma Aβ42 among all participants (r = 0.51, p < 0.001; data not shown).

We assessed the cross-sectional correlations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 with metabolic parameters among healthy participants in the case–control study (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1). Plasma Aβ40 was significantly correlated with FPG, FPI, HOMA-IR and triacylglycerol level (r = 0.088–0.134) when adjusted for age, sex, BMI, current smoking status, current drinking status, physical activity, family history of diabetes and hypertension. In addition, plasma Aβ42 was significantly related to LDL-C after these adjustments (r = 0.066).

Association of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentration with type 2 diabetes

The associations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentration with odds of type 2 diabetes are presented in Table 2. In multivariable adjustment model, the ORs for type 2 diabetes were 1.97 (95% CI 1.46, 2.66) for plasma Aβ40 and 2.01 (95% CI 1.50, 2.69) for plasma Aβ42, when comparing the highest quartile with the lowest quartile of plasma Aβ concentrations. Each 30 ng/l increment of plasma Aβ40 was associated with 28% (95% CI 15%, 43%) higher odds of type 2 diabetes, and each 5 ng/l increment of plasma Aβ42 was associated with 37% (95% CI 21%, 55%) higher odds of type 2 diabetes. In stratified analyses, the positive associations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 with type 2 diabetes were consistently observed across different subgroups defined by sex, BMI, physical activity, and hypertension (ESM Figs 1 and 2). The association of plasma Aβ40 with type 2 diabetes seemed to be stronger in individuals who did not drink alcohol (p for interaction =0.030). Meanwhile, the association of plasma Aβ42 with type 2 diabetes seemed to be stronger in individuals aged ≤50 years (p for interaction <0.001) or in those who did not partake in physical activity (p for interaction =0.030).

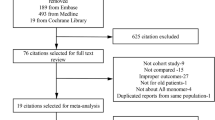

Joint association of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentration with type 2 diabetes

We explored the joint effects of plasma Aβ40 and plasma Aβ42 on the odds of type 2 diabetes by classifying participants by levels of both variables (Fig. 1 and ESM Table 2). Individuals in the highest tertile of both plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations had much higher odds of type 2 diabetes (adjusted OR 2.96 [95% CI 2.06, 4.25]) compared with those in the lowest tertile of both plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations. There was no significant interaction between plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 on the odds of type 2 diabetes (p for interaction =0.239).

Nested case–control study with a prospective design

Baseline characteristics of participants

The nested case–control study included 121 participants with incident type 2 diabetes and 242 matched control participants. The baseline characteristics of all participants are shown in Table 3. Consistent with the initial case–control study, plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations were significantly higher in individuals with type 2 diabetes vs control participants. Meanwhile, participants with type 2 diabetes had higher levels of FPG and triacylglycerol and a greater prevalence of family history of diabetes compared with the control participants.

We also assessed the prospective correlations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 with metabolic parameters among healthy participants in the nested case–control study (ESM Table 3). However, there was no significant correlation of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 with metabolic parameters.

Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentration in relation to subsequent odds of type 2 diabetes

Similar to the results of the initial case–control study, we observed positive associations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentration with odds of type 2 diabetes in the nested case–control study (Table 4). The multivariable-adjusted ORs of type 2 diabetes for the highest vs the lowest quartile were 3.79 (95% CI 1.81, 7.94) for plasma Aβ40 and 2.88 (95% CI 1.44, 5.75) for plasma Aβ42. The multivariable-adjusted ORs of type 2 diabetes associated with each 30 ng/l increment in plasma Aβ40 and each 5 ng/l increment in plasma Aβ42 were 1.44 (95% CI 1.18, 1.74) and 1.47 (95% CI 1.15, 1.88), respectively.

Discussion

With an initial phase including a large case–control study and a validation phase in a prospective cohort in two independent populations, we found consistent and positive associations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 with type 2 diabetes. The positive associations remained consistent across almost all subgroups. In addition, individuals in the highest tertile of both plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations had much higher odds of type 2 diabetes compared with those in the lowest tertile of both plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations.

According to previous studies, the mean/median concentrations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 in healthy individuals were in the ranges of 90.2–233.3 ng/l and 9.1–44.0 ng/l, respectively [19, 21,22,23,24]. Considering that elevated Aβ accumulation is implicated in the brain ageing process, age might be a major factor contributing to the variations in plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations across populations. Compared with our results, individuals who were older had higher plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations in almost all studies [19, 21, 23, 24]. In another study, younger individuals (mean age, 38 years) had lower plasma Aβ40 (mean, 90.2 ng/l) and Aβ42 (mean, 9.1 ng/l) concentrations [22]. Meanwhile, our study found that plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 were positively related to age (data not shown), which is consistent with a previous study [25]. In addition, plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations have been reported to be related to other factors than those reported in our study, including genetic predisposition, hepatic and renal function and cardiovascular factors [26,27,28,29]. They also varied depending on measurement method [24]. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the wide variations in plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations.

Our study is the first that has used a prospective study to demonstrate positive associations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentration with risk of type 2 diabetes. Consistent with our findings, a previous case–control study with only 62 participants found that plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations were significantly higher in individuals with hyperglycaemia compared with control participants [14]. Serum Aβ autoantibody levels, which reflect plasma Aβ concentrations within a defined period, were also previously reported to be higher in individuals with type 2 diabetes [18]. In addition, our findings are in line with the results from previous animal studies [15, 16]. Yet, unlike our findings, another case–control study found lower plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations in participants with type 2 diabetes compared with individuals in the control group [19]. The participants included in the aforementioned study had long-standing diabetes with use of glucose-lowering medication, which is an important confounder for plasma Aβ [30,31,32]. In our study, we included individuals with newly diagnosed or new-onset type 2 diabetes to rule out this confounder and observed significantly positive associations. Notably, the difference between our study and the previous study [19] indicates that diabetes progress and use of glucose-lowering medication should be taken into consideration in studies focusing on plasma Aβ. Additionally, plasma Aβ was primarily investigated as a potential biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease and a meta-analysis of seven prospective studies found higher plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations in cognitively normal individuals who eventually developed Alzheimer’s disease [33]. Our results, combined with the previous study [33], suggest that plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 might be important molecules underlying the relationship between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease.

Several biological mechanisms might explain how plasma Aβ increases risk of type 2 diabetes. First, Aβ could directly compete for insulin binding to the insulin receptor due to Aβ and insulin sharing a common sequence recognition motif [34], which might weaken insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, mainly including liver, muscle and adipose tissues. Likewise, Aβ and insulin are substrates for insulin degrading enzyme, and Aβ might affect insulin catabolism by regulating insulin degrading enzyme. Supporting this hypothesis, a previous study demonstrated that ablation of App increased insulin degrading enzyme levels and activity and decreased FPI [35]. We also found that plasma Aβ40 was positively associated with FPG, FPI and HOMA-IR among healthy participants in the case–control study. However, although the correlation between plasma Aβ40 and FPG among healthy participants in the nested case–control study was in the same direction, it did not reach statistical significance. This may be explained by the smaller sample size in the nested case–control study and the differences in participant characteristics between the two independent studies. Second, increasing plasma Aβ by intraperitoneally injecting Aβ42 activated hepatic Janus kinase 2 [16], which was related to insulin resistance induced by cytokines. Accordingly, neutralisation of plasma Aβ with anti- Aβ-neutralising antibodies inhibited hepatic Janus kinase 2 and markedly decreased plasma glucose and insulin levels. Third, plasma Aβ could induce damage of the pancreas through promoting deposition of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), which is one of the main pathologies of type 2 diabetes. Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations were found to be positively associated with plasma IAPP levels in the general population; meanwhile, cross-seeding between IAPP and Aβ has been described in in vitro studies [36, 37]. Previous autopsy results directly indicated that Aβ was co-localised with IAPP in islet amyloid deposits in the pancreas of donors with type 2 diabetes [38]. Finally, Aβ could constrict capillaries via signalling to pericytes, reducing blood flow [39], which might impair islet insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues [40].

There are several strengths in our study. First, we performed a case–control study with a large number of cases and a nested case–control study, which for the first time prospectively explored the association of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 with type 2 diabetes. Second, cases in our study were confined to newly diagnosed or new-onset, drug-naive participants to avoid the impact of diabetes progression and medication history, and each case was well matched by age and sex with one (case–control study) or two (nested case–control study) controls to better control for the influence of age and sex. Third, we used a validated MSD electrochemiluminescence multiplex assay to detect plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations, which exhibits several advantages compared with traditional ELISAs, such as simultaneous processing of plasma Aβ species and more efficiently detecting plasma Aβ [41, 42]. Meanwhile, concentrations of cerebrospinal fluid Aβ measured by the MSD immunoassay have been reported to be strongly correlated with the antibody-independent mass spectrometry-based reference measurement procedure [43].

There are also several limitations to our study that should be acknowledged. First, although we identified plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 as new predictors for type 2 diabetes, we could not establish a causal relationship between plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 and type 2 diabetes given the observational study design. Meanwhile, we could not rule out the possibility of residual confounding, despite taking many major risk factors into account in our study. Second, individuals with new-onset type 2 diabetes in the nested case–control study were diagnosed only according to FPG. However, considering that individuals with type 2 diabetes had higher plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations, the positive associations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentration with type 2 diabetes would not be reversed or may even become stronger if false-negative control participants were excluded. Finally, the ethnicity of all participants was limited (all participants were Chinese) and whether our findings apply to other ethnicities is unclear.

In conclusion, our study suggested positive associations of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentration with risk of type 2 diabetes. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and explore the potential role of plasma Aβ in linking type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Aβ:

-

β-Amyloid

- APP:

-

Amyloid precursor protein

- FPG:

-

Fasting plasma glucose

- FPI:

-

Fasting plasma insulin

- HDL-C:

-

HDL-cholesterol

- IAPP:

-

Islet amyloid polypeptide

- LDL-C:

-

LDL-cholesterol

- MSD:

-

Meso Scale Discovery

- NGT:

-

Normal glucose tolerance

- TJEZ:

-

Tongji-Ezhou cohort

References

Chatterjee S, Khunti K, Davies MJ (2017) Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 389(10085):2239–2251. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30058-2

Zhang J, Chen C, Hua S et al (2017) An updated meta-analysis of cohort studies: diabetes and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 124:41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2016.10.024

Craft S, Zallen G, Baker LD (1992) Glucose and memory in mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 14(2):253–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/01688639208402827

Fujisawa Y, Sasaki K, Akiyama K (1991) Increased insulin levels after OGTT load in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with dementia of Alzheimer type. Biol Psychiatry 30(12):1219–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3223(91)90158-i

Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O’Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC (2004) Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 53(2):474–481. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.53.2.474

Baglietto-Vargas D, Shi J, Yaeger DM, Ager R, LaFerla FM (2016) Diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease crosstalk. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 64:272–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.005

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (2016) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388(10053):1545–1602. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31678-6

Goate A, Chartier-Harlin MC, Mullan M et al (1991) Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 349(6311):704–706. https://doi.org/10.1038/349704a0

Moran C, Beare R, Phan TG, Bruce DG, Callisaya ML, Srikanth V (2015) Type 2 diabetes mellitus and biomarkers of neurodegeneration. Neurology 85(13):1123–1130. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000001982

Abner EL, Nelson PT, Kryscio RJ et al (2016) Diabetes is associated with cerebrovascular but not Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Alzheimers Dement 12(8):882–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.006

Lu Y, Jiang X, Liu S, Li M (2018) Changes in cerebrospinal fluid tau and β-amyloid levels in diabetic and prediabetic patients: a meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci 10:271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00271

Xiang Y, Bu XL, Liu YH et al (2015) Physiological amyloid-beta clearance in the periphery and its therapeutic potential for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 130(4):487–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1477-1

Roberts KF, Elbert DL, Kasten TP et al (2014) Amyloid-beta efflux from the central nervous system into the plasma. Ann Neurol 76(6):837–844. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24270

Zhang Y, Zhou B, Zhang F et al (2012) Amyloid-beta induces hepatic insulin resistance by activating JAK2/STAT3/SOCS-1 signaling pathway. Diabetes 61(6):1434–1443. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-0499

Wijesekara N, Ahrens R, Sabale M et al (2017) Amyloid-beta and islet amyloid pathologies link Alzheimer disease and type 2 diabetes in a transgenic model. FASEB J 31(12):5409–5418. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201700431R

Zhang Y, Zhou B, Deng B et al (2013) Amyloid-beta induces hepatic insulin resistance in vivo via JAK2. Diabetes 62(4):1159–1166. https://doi.org/10.2337/db12-0670

Balakrishnan K, Verdile G, Mehta PD et al (2005) Plasma Aβ42 correlates positively with increased body fat in healthy individuals. J Alzheimers Dis 8(3):269–282. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-2005-8305

Kim I, Lee J, Hong HJ et al (2010) A relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus through the measurement of serum amyloid-beta autoantibodies. J Alzheimers Dis 19(4):1371–1376. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-2010-1332

Peters KE, Davis WA, Taddei K et al (2017) Plasma amyloid-β peptides in type 2 diabetes: a matched case-control study. J Alzheimers Dis 56(3):1127–1133. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-161050

Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ (1998) Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 15(7):539–553. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::aid-dia668>3.0.co;2-s

Chouraki V, Beiser A, Younkin L et al (2015) Plasma amyloid-β and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in the Framingham Heart Study. Alzheimers Dement 11(3):249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.07.001

Iulita MF, Ower A, Barone C et al (2016) An inflammatory and trophic disconnect biomarker profile revealed in Down syndrome plasma: relation to cognitive decline and longitudinal evaluation. Alzheimers Dement 12(11):1132–1148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.05.001

Lambert JC, Schraen-Maschke S, Richard F et al (2009) Association of plasma amyloid beta with risk of dementia: the prospective Three-City Study. Neurology 73(11):847–853. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b78448

Yaffe K, Weston A, Graff-Radford NR et al (2011) Association of plasma beta-amyloid level and cognitive reserve with subsequent cognitive decline. JAMA 305(3):261–266. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1995

Mayeux R, Honig LS, Tang MX et al (2003) Plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 and Alzheimer’s disease: relation to age, mortality, and risk. Neurology 61(9):1185–1190. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000091890.32140.8f

Liu YH, Xiang Y, Wang YR et al (2015) Association between serum amyloid-beta and renal functions: implications for roles of kidney in amyloid-beta clearance. Mol Neurobiol 52(1):115–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-014-8854-y

Chouraki V, De Bruijn RF, Chapuis J et al (2014) A genome-wide association meta-analysis of plasma Abeta peptides concentrations in the elderly. Mol Psychiatry 19(12):1326–1335. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.185

Bates KA, Sohrabi HR, Rodrigues M et al (2009) Association of cardiovascular factors and Alzheimer’s disease plasma amyloid-beta protein in subjective memory complainers. J Alzheimers Dis 17(2):305–318. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-2009-1050

Wang YR, Wang QH, Zhang T et al (2017) Associations between hepatic functions and plasma amyloid-beta levels—implications for the capacity of liver in peripheral amyloid-beta clearance. Mol Neurobiol 54(3):2338–2344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-016-9826-1

Stanley M, Macauley SL, Caesar EE et al (2016) The effects of peripheral and central high insulin on brain insulin signaling and amyloid-β in young and old APP/PS1 mice. J Neurosci 36(46):11704–11715. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.2119-16.2016

Swaminathan SK, Ahlschwede KM, Sarma V et al (2017) Insulin differentially affects the distribution kinetics of amyloid beta 40 and 42 in plasma and brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 38(5):904–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678X17709709

Tamaki C, Ohtsuki S, Terasaki T (2007) Insulin facilitates the hepatic clearance of plasma amyloid β-peptide (1–40) by intracellular translocation of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1) to the plasma membrane in hepatocytes. Mol Pharmacol 72(4):850–855. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.107.036913

Song F, Poljak A, Valenzuela M, Mayeux R, Smythe GA, Sachdev PS (2011) Meta-analysis of plasma amyloid-beta levels in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 26(2):365–375. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-2011-101977

Xie L, Helmerhorst E, Taddei K, Plewright B, Van Bronswijk W, Martins R (2002) Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptides compete for insulin binding to the insulin receptor. J Neurosci 22(10):RC221. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-j0001.2002

Kulas JA, Franklin WF, Smith NA et al (2019) Ablation of amyloid precursor protein increases insulin-degrading enzyme levels and activity in brain and peripheral tissues. Am J Phys Endocrinol Metab 316(1):E106–E120. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00279.2018

O’Nuallain B, Williams AD, Westermark P, Wetzel R (2004) Seeding specificity in amyloid growth induced by heterologous fibrils. J Biol Chem 279(17):17490–17499. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M311300200

Ono K, Takahashi R, Ikeda T, Mizuguchi M, Hamaguchi T, Yamada M (2014) Exogenous amyloidogenic proteins function as seeds in amyloid beta-protein aggregation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842(4):646–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.01.002

Miklossy J, Qing H, Radenovic A et al (2010) Beta amyloid and hyperphosphorylated tau deposits in the pancreas in type 2 diabetes. Neurobiol Aging 31(9):1503–1515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.019

Nortley R, Korte N (2019) Amyloid beta oligomers constrict human capillaries in Alzheimer’s disease via signaling to pericytes. Science 365(6450):eaav9518. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav9518

Richards OC, Raines SM, Attie AD (2010) The role of blood vessels, endothelial cells, and vascular pericytes in insulin secretion and peripheral insulin action. Endocr Rev 31(3):343–363. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2009-0035

Oh ES, Mielke MM, Rosenberg PB et al (2010) Comparison of conventional ELISA with electrochemiluminescence technology for detection of amyloid-beta in plasma. J Alzheimers Dis 21(3):769–773. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-2010-100456

Stenh C, Englund H, Lord A et al (2005) Amyloid-beta oligomers are inefficiently measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Ann Neurol 58(1):147–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20524

Janelidze S, Pannee J, Mikulskis A et al (2017) Concordance between different amyloid immunoassays and visual amyloid positron emission tomographic assessment. JAMA Neurol 74(12):1492–1501. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2814

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants in the two studies for their tireless dedication. We also thank X. Yu (Division of Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China), and C. Xia and J. Zhang (Health Management Center, Ezhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Ezhou, China) for their assistance in data collection.

Authors’ relationships and activities

The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC1600500), the Major International (Regional) Joint Research Project (NSFC 81820108027) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773423 and 21537001). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XBP, ZX and LL designed the study. XBP, ZX, XM, QG, JY, MX, ZP, TS, LZ, XLP, SX, WY, WB, ZS and XL contributed to the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data collection. XBP wrote the manuscript. ZX, XM, QG, JY, MX, ZP, TS, LZ, XLP, SX, WY, WB, ZS, XL and LL contributed to reviewing and revising the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. LL is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM

(PDF 206 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, X., Xu, Z., Mo, X. et al. Association of plasma β-amyloid 40 and 42 concentration with type 2 diabetes among Chinese adults. Diabetologia 63, 954–963 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05102-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05102-x