Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

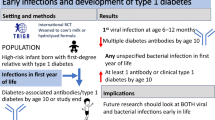

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease resulting from a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is one of the environmental factors implicated in the development of type 1 diabetes, although the association remains unproven. We aimed to clarify the possible correlation between CMV infections and type 1 diabetes-associated autoimmunity at the time point of autoantibody appearance in young children with HLA-conferred disease susceptibility.

Methods

CMV-specific IgG antibodies were analysed from serum samples of 169 children who had developed the first type 1 diabetes-associated autoantibody by the age of 2 years and who turned positive for multiple autoantibodies during later follow-up. We also studied 791 control children matched for sex, age and HLA genotype. The subsequent progression to clinical diabetes was analysed. The serum specimens used were collected at the time of autoantibody seroconversion or within the next 6 months.

Results

The frequency of CMV antibodies was similar in both study groups at the time of the first autoantibody appearance. Of the index children, 38 (22.5%) were CMV IgG antibody-positive, while the figure for control children was 206 (26.0%; p = 0.38). No association between perinatal CMV infection and progression to type 1 diabetes was observed.

Conclusions/interpretation

According to these results, perinatal CMV infections are not associated with early serological signs of beta cell autoimmunity or progression to type 1 diabetes in children with diabetes risk-associated HLA genotype.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Both genetic and environmental factors strongly contribute to the disease process in type 1 diabetes. The HLA gene complex is of primary importance in determining genetic disease susceptibility, being responsible for about half of the genetic risk component [1]. Among environmental factors a series of viruses including cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections have been associated with the development of beta cell autoimmunity [2].

CMV is a ubiquitous herpes group virus causing chronic life-long infection in affected participants. CMV infection is already relatively common among small children. In the Finnish population, 27% of infants at the age of 7 months tested positive for CMV IgG antibodies [3]. In infants and early childhood the most common route for CMV transmission is perinatal infection through maternal genital secretion or breast milk.

In previous studies, results on the association of CMV infection with type 1 diabetes have been contradictory. Pak et al. [4] found a strong correlation between the CMV genome detectable in lymphocytes and islet cell autoantibodies in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Nicoletti et al. [5] reported a significant association between high titres of anti-CMV IgG antibodies and islet cell antibodies (ICA). Recent studies have also shown that asymptomatic CMV infection is associated with increased risk of new-onset type 1 diabetes and impaired insulin release after renal transplantation [6]. On the other hand, Hiltunen et al. [7] did not find any correlation between the presence of CMV IgG antibodies and ICA in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. They did not find any temporal association between CMV seroconversion and the appearance of islet cell autoantibodies or the manifestation of clinical diabetes in initially non-diabetic siblings of affected children.

Accordingly, the number of studies about the possible connection between CMV and type 1 diabetes still remains small and the results are controversial. In particular, a limited number of studies have analysed the role of CMV at the initiation of diabetes-specific autoimmunity [7]. We aimed to clarify the role played by early, mostly perinatal, infection in the appearance of diabetes-associated autoantibodies in young children carrying the HLA genotype associated with type 1 diabetes risk.

Methods

Participants

The study cohort was derived from the Finnish Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention (DIPP) Study, in which newborn infants with HLA-conferred risk were recruited for a cohort that is followed for the appearance of signs of diabetes-associated autoimmunity (ICA, insulin autoantibodies, 65 kDa isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD65) antibodies, tyrosine phosphatase-related islet antigen 2 antibodies) [8].

The local ethics committees approved the study and informed consent was obtained from the parents of the participants.

Study design

CMV-specific IgG class antibodies were analysed from serum samples. These were taken: (1) from 169 children (67 girls; age 0.5–2.0 years, median age 1.3 years) who had developed their first diabetes-associated autoantibody by the age of 2 years and who later turned positive for multiple (two or more) autoantibodies; and (2) from 791 control participants (326 girls; age 0.5–2.0 years, median 1.3 years, three to five control participants per case, median five controls) matched for sex, HLA-DQB1 genotype and birth date (born within 1 month before or after the birth of the index participant). If there were more than five controls fulfilling the criteria, those with birth dates closest to the index case were selected. The number of controls per case varied due to the lack of appropriate serum samples from some of the autoantibody-negative control participants. CMV antibodies were analysed from the serum specimen collected at the time of autoantibody seroconversion or within the next 6 months.

The association of perinatal CMV infection with progression rate to clinical diabetes was analysed among the 960 study participants and in a subgroup of 169 multiple autoantibody-positive children. The length of the prospective follow-up was 2.7 to 12.3 years (median 7.5 years) in CMV-positive children and 2.7 to 12.4 years (median 7.2 years) in CMV-negative children.

Analysis and measurements

The IgG class antibodies to CMV were analysed using enzyme immunoassay as described earlier [9]. A positive result was defined as an absorbance at least three times higher than the absorbance of a negative control. The assays for autoantibodies and their detection limits have been described earlier [10]. HLA genotyping for the study was performed as described [11]. All statistical analyses were performed using StatView (5.0.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

IgG class antibodies to CMV were analysed in 169 children who became positive for multiple diabetes-associated autoantibodies during the follow-up and had been positive for at least one of the autoantibodies at the age of 2 years. The prevalence of CMV antibody positivity was compared with the findings in 791 control children matched for sex, age and HLA-DQB1 genotype.

The frequency of CMV antibodies at the time of the first autoantibody appearance was similar to that seen in the controls. Of the 169 index children, 38 (22.5%) were positive for CMV IgG antibodies compared with 206 of the 791 control children (26.0%; p = 0.38; χ 2 with continuity correction; Table 1). In Kaplan–Meier analysis, CMV seropositivity did not correlate with the appearance rate of any of the specific autoantibodies (NS; Mantel–Cox). There was no difference in the prevalence of CMV antibodies between participants positive for the HLA-DR4-DQ8 haplotype, participants positive for DR3-DQ2 haplotype and those heterozygous for the DR3-DQ2 and DR4-DQ8 haplotypes (p = 0.61).

When the effect of perinatal CMV infection on progression to clinical diabetes was analysed among the study population, no association between perinatal CMV infection and development of type 1 diabetes could be observed. During the prospective follow-up 16 (6.6%) of the 244 CMV-positive children developed clinical type 1 diabetes compared with 74 (10.3%) of the 716 CMV-negative children (p = 0.098, χ 2 test with continuity correction). The progression rate to clinical type 1 diabetes did not differ between the groups (p = 0.078, Mantel–Cox; Fig. 1a). Among the subgroup of 169 autoantibody-positive participants, 38 (22.5%) children were positive for CMV IgG class antibodies at the time of appearance of the first autoantibody or within 3 to 6 months after it. Within this subgroup, 16 (42.1%) of the CMV-positive children and 74 (56.5%) of the CMV-negative children progressed to type 1 diabetes during the subsequent follow-up; however, the difference remained non-significant (p = 0.17; χ 2 with continuity correction). The rate of progression to type 1 diabetes did not differ between participants with or without CMV antibodies (Fig. 1b).

The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed no association between CMV infection in early infancy and progression to clinical type 1 diabetes in a cohort of 960 children carrying HLA-conferred type 1 diabetes risk. a Of the CMV-seropositive (dashed line) and CMV-seronegative (continuous line) children, 6.6 and 10.3% respectively developed type 1 diabetes (p = 0.078; Mantel–Cox). Similarly (b), when the progression rate to clinical diabetes was analysed among the 169 participants who developed the first diabetes-related autoantibody by the age of 2 years, no significant difference among CMV-positive (dashed line) and CMV-negative (continuous line) participants could be observed (42.1 vs 56.5%, respectively; p = 0.19 [Mantel–Cox])

Discussion

It is often suspected that virus infections may provoke type 1 diabetes in genetically susceptible individuals. Direct destruction of beta cells by the viral infection, immune-mediated destruction by cross-reacting T cells or non-specific enhancement of antigen presentation have been suggested to be the underlying pathogenic mechanisms [2].

T cell cross-reaction by molecular mimicry has been considered as a possible mechanism by which CMV could trigger the autoimmune process. In support of the hypothesis, homology between GAD65 and sequences of CMV US22 gene family encoding proteins HHLF5 and HWLF have been described, but it has not been reported whether these regions actually serve as T cell epitopes [12]. However, Hiemstra et al. [13] reported GAD65-specific T cell cross-reactivity with a peptide of the major DNA-binding protein of CMV. This CMV-derived epitope could also be naturally processed by dendritic cells. These results suggest that CMV may be involved in the loss of T cell tolerance to the GAD65 autoantigen by a mechanism of molecular mimicry leading to autoimmunity.

In this study we analysed the CMV IgG class antibodies from 169 children who tested positive for multiple diabetes-associated autoantibodies and had been positive for at least one of the autoantibodies at the age of 2 years. The frequency of CMV antibodies was compared with the findings in 791 control children matched for sex, age and HLA-DQB1 genotype. The results revealed no difference in CMV seropositivity between the two groups at the time of the initial autoantibody seroconversion. The number of cases and control participants available would have allowed the detection of a 50% increase in the proportion of multiple autoantibody-positive participants at a level of 5% significance (power 80%).

During the perinatal period, CMV infection is mostly transmitted through breast milk and the duration of breast-feeding might affect the rate of CMV seropositivity. Although controversial, long duration of breast-feeding and/or late introduction of cows’ milk-based formulas have repeatedly been associated with protection against type 1 diabetes [14]. The duration of breast-feeding might thus be considered to be a confounding factor explaining the lesser appearance of clinical disease in CMV-positive children. However, when the effect of the duration of breast-feeding was analysed, no significant difference was observed, although CMV infection was especially rare (1/12 = 8%) among the infants with a very short breast-feeding period (0–4 weeks; data not shown).

In summary, we found no association between CMV infection in early infancy and the early appearance of beta cell autoimmunity or progression to clinical disease in children carrying type 1 diabetes risk-associated HLA-DQB1 genotypes. However, it should be noted that we have analysed a specific subgroup of young children in Finland and the effect of perinatal CMV infection on the progression of beta cell autoimmunity acquired at an early age. CMV infections occurring at an older age or in populations with different genetic backgrounds may have different effects.

Abbreviations

- CMV:

-

cytomegalovirus

- GAD65:

-

65 kDA isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase

- ICA:

-

islet cell antibodies

References

Field LL (2002) Genetic linkage and association studies of type 1 diabetes: challenges and rewards. Diabetologia 45:21–35

Jun HS, Yoon JW (2003) A new look at viruses in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 19:8–31

Aarnisalo J, Ilonen J, Vainionpää R, Volanen I, Kaitosaari T, Simell O (2003) Development of antibodies against cytomegalovirus, varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in Finland during the first eight years of life: a prospective study. Scand J Infect Dis 35:750–753

Pak CY, Eun HM, McArthur RG, Yoon JW (1988) Association of cytomegalovirus infection with autoimmune type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2:1–4

Nicoletti F, Scalia G, Lunetta M et al (1990) Correlation between islet cell antibodies and anti-cytomegalovirus IgM and IgG antibodies in healthy first-degree relatives of type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 55:139–147

Hjelmesaeth J, Sagedal S, Hartmann A et al (2004) Asymptomatic cytomegalovirus infection is associated with increased risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus and impaired insulin release after renal transplantation. Diabetologia 47:1550–1556

Hiltunen M, Hyöty H, Karjalainen J, The Childhood Diabetes in Finland Study Group et al (1995) Serological evaluation of the role of cytomegalovirus in the pathogenesis of IDDM: a prospective study. Diabetologia 38:705–710

Kupila A, Muona P, Simell T et al (2001) Feasibility of genetic and immunological prediction of type I diabetes in a population-based birth cohort. Diabetologia 44:290–297

Ziegler T, Meurman O, Nikoskelainen J, Arstila P (1987) Laboratory diagnosis of herpes virus infections in immunocompromised hosts. Ann Ist Super Sanita 23:747–752

Kimpimäki T, Kulmala P, Savola K et al (2002) Natural history of beta-cell autoimmunity in young children with increased genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes recruited from the general population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:4572–4579

Hermann R, Knip M, Veijola R et al (2003) Temporal changes in the frequencies of HLA genotypes in patients with type 1 diabetes—indication of an increased environmental pressure? Diabetologia 46:420–425

Jones DB, Crosby I (1996) Proliferative lymphocyte responses to virus antigens homologous to GAD65 in IDDM. Diabetologia 39:1318–1324

Hiemstra HS, Schloot NC, van Veelen PA et al (2001) Cytomegalovirus in autoimmunity: T cell crossreactivity to viral antigen and autoantigen glutamic acid decarboxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:3988–3991

Knip M, Veijola R, Virtanen SM, Hyöty H, Vaarala O, Åkerblom HK (2005) Environmental triggers and determinants of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 54(Suppl 2):S125–S136

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the entire Diabetes Prediction and Prevention Study personnel, as well as all study children and their families for their irreplaceable contribution. We thank P. Nurmi and M. Maaronen for their skilful technical assistance. This study was financially supported by the Turku Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation and the Finnish Cultural Foundation.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aarnisalo, J., Veijola, R., Vainionpää, R. et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in early infancy: risk of induction and progression of autoimmunity associated with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 51, 769–772 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-0945-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-0945-8