Abstract

Cross laminated timber (CLT) and self-tapping screws have strongly dominated the latest developments in timber engineering. Although knowledge of connection techniques in traditional light-frame structures can be applied to solid timber constructions with CLT, there are some product specifics requiring additional attention; for example in positioning of fasteners, differentiation in the side face and narrow face of the panels and the influence of potential gaps. The load–displacement behaviour of single, axially-loaded self-tapping screws positioned in the narrow face of CLT and failing in withdrawal was investigated. For the first time a multivariate probabilistic model was formulated together with models relating the parameters with the thread-fibre angle and the density. Different types and widths of gaps, initial slip and / or delayed stiffening as well as softening after exceeding of the maximum load can be considered. Beyond the scope of this contribution, the probabilistic model is seen as a worthwhile basis for investigations into the withdrawal behaviour of primary axially loaded, compact groups of screws positioned in timber products and subjected to withdrawal failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Cross laminated timber (CLT), as a laminar engineered timber product, and self-tapping screws, as metal fasteners, have strongly dominated the latest developments in timber engineering. Both innovations have considerably contributed to the increasing market share of timber structures in the overall building market, in particular in Europe, in countries like Austria, Germany and United Kingdom (e.g. Teischinger et al. 2011; Statistisches Bundesamt 2016; Lane 2014). Whereas CLT opens up new horizons in timber engineering, in areas which had until now been the realm of mineral building materials such as concrete and masonry, fully or partially threaded self-tapping screws, optimized for load-bearing in axial direction, facilitate economic and versatile applications. Although existing knowledge from linear timber members can also be widely used for connecting CLT elements, some product specifics require additional attention; for example in positioning of fasteners, differentiation in side (the plane surface of CLT) and narrow face (the cross section of CLT). Up to now, there are only a few investigations available focusing on the behaviour of single fasteners and in particular on self-tapping screws in CLT (e.g. Blaß and Uibel 2007, 2009; Reichelt 2012; Grabner 2013; Silva et al. 2014; Ringhofer et al. 2014, 2015).

The behaviour and performance of fasteners interacting in a group depends decisively on the load–displacement behaviour of single fasteners, their variability and the workmanship. Focusing on the aleatoric uncertainty, accurate modelling of the load–displacement behaviour of single fasteners is of great importance for judging the capacity of the group in a reliable and economic way and for suggestions on the optimal design and use of the fasteners. Although research on the load–displacement behaviour of single fasteners and probabilistic models are available, none of these investigations consider the withdrawal behaviour of axially loaded self-tapping screws. For adequate modelling of the load–displacement behaviour of groups of self-tapping screws, additional consideration of softening after exceeding the maximum load is mandatory, a circumstance that has so far not been covered in existing research into timber engineering, which focuses on dowel-type fasteners stressed in shear rather than on axially loaded fasteners.

In addition to these general circumstances, which are relevant for axially loaded screws positioned in any kind of timber product, there are some important specifics to consider when screws are placed in CLT. Apart from the necessity to differentiate in side and narrow face, the layup of CLT, its orthogonal structure, cause a variety of product parameters potentially influencing the product’s properties and hence also the withdrawal properties of screws in CLT. Overall, the main CLT product parameters of interest for screws failing in withdrawal are the orientation and dimension of layers and lamellas, the execution of the narrow face (with or without bonding), types and widths of gaps and stress relief within layers.

With focus on screws in the narrow face of CLT, the possibility of gaps between boards within one or in between different layers, and the possibility of screws featuring different thread-fibre angles α along their circumference require consideration; see Fig. 1. In all these cases, withdrawal properties may be influenced remarkably.

1.1 State of knowledge of axially loaded self-tapping screws positioned in the narrow face of CLT

There are only a few investigations into the withdrawal behaviour of axially loaded self-tapping screws positioned in the narrow face of CLT. The first known comprehensive study is reported in Blaß and Uibel (2007). Withdrawal tests were made using industrially produced CLT of three and five layers with and without bonding on the narrow face. Investigations also included the influence of positioning screws in different types of gaps. However, as the width of the gaps varied randomly from test to test, and were on average only 0.5–2.0 mm wide, a direct relationship between withdrawal strength and the type and width of the gaps cannot be determined. Furthermore, tests were restricted to thread-fibre angles of 0°, 90° and combinations of both. The ratio between the average withdrawal strengths at 90° and 0° was found with f ax,90,mean/f ax,0,mean = 1.25 and the approach used by Hankinson (1921) (see Sect. 3.1) was applied. The influence of density on f ax was described by a power model with exponent 0.75. In comparison to Blaß et al. (2006), who investigated the withdrawal capacity of axially loaded screws in solid timber, minor conservative but overall congruent regression models were determined. Based on their research in 2007, Blaß and Uibel (2009) suggested using the characteristic withdrawal parameter given a thread-fibre angle of 0° (f ax,k|α = 0° = f ax,0,k = 0.67f ax,90,k) for a simplified design of axially-loaded self-tapping screws in the narrow face of CLT, irrespective of the orientation of the corresponding layer and thus irrespective of the thread-fibre angle α.

1.2 State of knowledge of modelling of the load–displacement behaviour of single fasteners and groups of fasteners

Numerous studies have focused on modelling the load–displacement behaviour of fasteners; for a summary and confrontation see Attiogbe and Morris (1991).

Foschi (1974), for example, used an exponential model for modelling the foundation properties of nails stressed in shear. Richard and Abbott (1975) defined a power model which can be applied to describe the load–displacement behaviour of metal fasteners in timber. The models of Foschi (1974) and Richard and Abbott (1975) were later extended, for example, by Blaß (1991) and Jaspart (1991), respectively, introducing ideal plastic yielding of the fastener after exceeding the maximum load.

Although these models have already been successfully used in probabilistic investigations into the behaviour of single fasteners and of the group action of fasteners (e.g. Blaß 1991), there are some decisive characteristics which limit their merit in modelling the withdrawal behaviour of axially loaded self-tapping screws; for example:

-

The point (F max; w f), with w f as the deformation associated with the maximum load F max, is not part of the previous mentioned models; thus, the relationship between F max and w f may not be accurately represented;

-

The extensions for both models assume ideal plastic yielding after exceeding F max; this approximation appears suitable for dowel-type fasteners such as nails or dowels stressed in shear; however, non-linear softening after exceeding F max, which is typical for self-tapping screws failing in withdrawal, is not provided.

Glos (1978) elaborated a polynomial model which allows also softening after exceeding the maximum load. His model has five parameters: in terms of a load–displacement curve, given as the initial stiffness k ser (at w = 0), F max and w f as the ultimate load and the corresponding displacement, respectively, F asym as asymptotic resistance at w → ∞ and exponent c as shape parameter. This exponent offers high flexibility in calibrating the model to the non-linear part of test data and constitutes the only non-mechanical material property. Although the model was originally developed to describe the stress–strain relationship of timber in compression parallel to grain, it has meanwhile also been used for other investigations, for example for reliability analyses of parallel systems, see Gollwitzer (1986) and Gollwitzer and Rackwitz (1990). Recently, Flatscher (2014) extended Glos’ model by an additional calibration parameter to improve the characterisation of load–displacement curves of various joints. Despite some limitations, Glos’ approach is seen as a worthwhile basis for modelling the load–displacement curve of axially loaded self-tapping screws. Its core is used and adapted later in Sect. 2.2.

2 Motivation and objective

The small number of probabilistic investigations on fasteners and joints in timber engineering in general and in particular the insufficient and fragmented knowledge of the behaviour of axially loaded self-tapping screws in the narrow face of CLT have motivated to establish a probabilistic model, usable for investigations aiming at a more reliable and perhaps even more economical joint design and application. Therefore, a probabilistic model approach was established, which allows an accurate and reliable characterization of the withdrawal behaviour of axially loaded self-tapping screws positioned in the narrow face of CLT. By modelling the load–displacement curve, initial slip or delayed stiffening at the beginning of loading as well as softening after exceeding the maximum load are addressed.

The model parameters were inferred from one of two independently conducted test series by Grabner (2013), the model was validated with data from the other test series conducted on screws influenced by gaps, and its predictive quality was demonstrated.

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Series of withdrawal tests

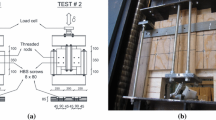

The data of two independently conducted test series on self-tapping screws positioned in the narrow face of CLT and tested in withdrawal originate from Grabner (2013). The five-layered CLT of both series was made of Central European Norway spruce (Picea abies). For testing of withdrawal, partially threaded screws ASSY 3.0 (d = 8 mm, d 1 = 5.5 mm, l = 400 mm, l thread = 100 mm; ETA-11/0190 2011) and ECOFAST ASSY II (d = 12 mm, d 1 = 7.2 mm, l = 440 mm, l thread = 140 mm; Z-9.1-514 2011) were used, with d and d 1 as the outer and inner thread diameter, respectively. The penetration length of the screw in CLT was 10 d = 80 and 120 mm for d = 8 and 12 mm, respectively. For calculation of withdrawal parameters, the effective length was defined as the penetration length minus the tip length, with l ef = 80–9.1 = 70.9 and 120–13.5 = 106.5 mm. In the case of pre-drilling, the drill diameters used were ≤ d 1, with 5 and 7 mm for screws of d = 8 and 12 mm, respectively.

All tests were conducted as push–pull tests and according to EN 1382 (1999) way-controlled (constant loading rate) with time to failure in 90 ± 30 s. A constant loading rate was applied to better characterise the softening behaviour. A pre-load of, on average, 150 N was used to fix the screw’s position in the centre of the circular hole in the counter plate and to reduce measurement artefacts at the beginning of loading. All screws were inserted parallel to the side face of CLT. Measurement of local deformations was performed only for screws of diameter d = 8 mm by using inductive displacement transducers until the load dropped down to ≤ 0.75 F max, with F max as the maximum load per test. The local deformations later used in analysis comprise both, the deformation of the screw part embedded in timber and the local deformation of timber. Thus, the deformation of the composite screw-timber is represented.

Local density and moisture content were determined according to ISO 3131 (1975) and EN 13183-1 (2002), respectively. The density of tests with screws placed in gaps was determined as sum of densities of all involved layers multiplied by their theoretical proportion. Tests of screws that penetrated or touched local growth characteristics, like knots, checks, reaction wood and resin pockets, were recorded. Based on a statistical data analysis (Grabner 2013), all tests with knots had to be excluded whereas tests with reaction wood and resin pockets remained in further data processing. All tests were performed at moisture content u = 12 ± 2%. Thus, a correction of test parameters to the reference moisture content of u ref = 12% was not required.

3.1.1 Test series I

Series I comprised tests in 160 mm thick industrially produced CLT elements with a base material of strength class C24 according to EN 338 (2009) and layer thicknesses (from top to top) of 40, 20, 40, 20 and 40 mm. The aim of the tests was to investigate (1) the influence of the thread-fibre angle α, (2) the influence of positioning screws in different layers and between layers, and (3) the influence of pre-drilling. Concerning (1) and (2), withdrawal parameters were determined in all layers of CLT (top layer, TL; cross layer, CL; and middle layer, ML) with α = 0°, 30°, 45°, 60° and 90°. Tests on screws positioned between two layers were accomplished for α = 0°|90° and 45°|45°. 20 tests were made for each parameter combination. To assure perfect positioning of all screws, in particular screws placed between two layers, pre-drilling was applied. Additional tests without pre-drilling were conducted in TL and for α = 0°, 45° and 90° to judge the influence of pre-drilling (3).

The data of series I is later used to infer model parameters. As the local deformations were only measured for screws of diameter

only these data sets can be used. Furthermore, only the data of screws positioned centrically in one layer are considered. As the comparison of withdrawal parameters based on tests with and without pre-drilling does not show any significant differences (Grabner 2013), further investigations are restricted to tests with pre-drilling for test execution in series II, see Table 1.

3.1.2 Test series II

To investigate the influence of gaps on the withdrawal parameters, the gap type and width w gap were varied, see Table 1. Three types of gaps, gaps between boards within the same layer (butt joint; BuJ), gaps between neighbouring layers (bed joint; BeJ) and a combination of both (T-joint; TJ) were examined using fixed gap widths of w gap = (0, 2, 6) mm (see Fig. 1). The range of w gap corresponds to common regulations currently anchored in technical approvals for CLT, see e.g. Brandner (2013a).

The CLT elements were produced in the laboratory at the Institute of Timber Engineering and Wood Technology at Graz University of Technology. They were composed of boards with strength class C16 according to EN 338 (2009) and with layer thicknesses (from top to top) of 37, 20, 37, 20 and 37 mm. To minimize the influence of growth characteristics in timber, for example knots, knot clusters and checks, all board segments featuring these characteristics were trimmed out. The residual board segments were mixed and afterwards, during the production of CLT, taken from the batch at random. In doing so, sub-series of CLT with comparable timber properties, i.e. densities, (matched samples) were obtained. Compliance with pre-defined gap widths was assured by step-by-step production, starting with surface bonding of two transverse layers in hydraulic press equipment at a bonding pressure of 0.4 N/mm2, by cutting of gaps, sealing the gaps with tape, preventing filling with adhesive, and by continuing the process until five-layer CLT elements were achieved.

Pre-drilling was applied to all tests to maximize the precision in the positioning of screws relative to the gaps. The data of series II is later used for validating the probabilistic model regarding the influence of gaps and mixed thread-fibre angles.

3.2 Modelling the load–displacement behaviour of single self-tapping screws failing in withdrawal

To represent the load–displacement curve of axially loaded self-tapping screws the core of Glos’ model (Glos 1978; see Sect. 1.2) is used and the following important adaptations and extensions are made:

-

At first, the approach is simplified by using F asym = 0. This is argued by the fact that a residual resistance F asym > 0 | w → ∞ cannot be observed in timber primarily stressed in longitudinal and / or lateral shear as this is the case in testing screws in timber against withdrawal.

-

Secondly, test data indicates delayed stiffening at the beginning of loading, which is a well-known characteristic of natural, hierarchically structured materials (e.g. see Gordon 1988). To account for this phenomenon, and as the principal shape of this first branch of the load–displacement curve is in general not decisive for engineering applications, a horizontal shift of the curve is introduced by Δw ini (see Fig. 2). This shift is not of relevance for single screws but may be of importance for investigations into the interaction of screws in groups. However, as a pre-load was applied (see Sect. 2.1) the available test data provides only underestimations for Δw ini. For modelling of single screws, Δw ini is set to zero.

-

As Glos’ model does not provide a linear-elastic part at the beginning of the load–displacement curve (see Fig. 2, right), which can be approximately observed from withdrawal tests with hysteresis loops, its stiffness parameter k ser | w = 0 does not correspond to k ser from tests usually determined according to EN 26891 (1991). This standard defines k ser as gradient of the load–displacement curve until 0.4 F max. For applicability of the standardized k ser as model parameter, a linear part Δw lin is introduced between w ini and w lin after which the model of Glos (1978) starts with k ser | w = w lin, see Fig. 2, left.

The corresponding formalisms for parameters k 1, k 2 and k 3 are also given in Eqs. (1–4).

with

and with parameters

and

As most of the data sets provide information at least until ≤ 0.75 F max in the softening domain (w > w f) it is aimed to provide stochastic information for model parameters up to this domain but control the representation by the model until the end of recorded data. All model parameters are determined directly from tests apart from the shape parameter c which is gained from calibrating the model to real data. If applicable, the parameters ∆w ini, ∆w lin, k ser, F max and w f of each data set were determined according to EN 26891 (1991). Additionally, parameters ∆w ini, ∆w lin and k ser are based on the apparent linear part (constant gradient) in the load–displacement curve, which, in the case of way-controlled testing, equals to a constant increase in load. This part of the load–displacement curve can easily be found by analysing the load increment per displacement increment, see Fig. 2, right. Thus, the apparent beginning and end of the constant part correspond to w ini and w lin, respectively, with k ser as gradient of F ax(w) vs. w.

3.3 Statistical analysis and inference

The statistical analysis and inference as well as modelling and simulation of virtual load–displacement curves is undertaken in R (2013).

For both test series of Grabner (2013) a comprehensive statistical analysis is made to infer reliable statistics for the model parameters in Sect. 2.2. Starting with harmonizing the data basis from test series I, including a density correction, representative distribution models for each parameter, as univariate variables, are determined. Apart from comparisons between statistics and expert judgements, additionally outcomes of pairwise t-tests, conducted on untransformed and logarithmized data sub-sets, and of the Mann–Whitney U test, as parameter-free test, are used to support the decisions; in frame of this hypothesis testing, with H0: Z = 0 vs. H1: Z ≠ 0, with

as pairwise comparison of mean and median values, respectively, assessing the significance level with 5%. Testing of logarithmized data is motivated by the circumstance that properties of timber are frequently well represented by a lognormal distribution and the background that logarithmized lognormal variables are normal distributed.

Regression analyses for the relationships between model parameters and α, and correlation analyses, to determine adequate and physically traceable correlations between the model parameters, are made. For decisions on correlations, estimates based on Pearson and the parameter free rank correlation coefficient of Spearman are tested on significance (significance level 5%) and compared.

To verify the multivariate model approach virtual load–displacement curves are generated with 1000 runs per parameter setting (gap type, gap width and screw diameter). By means of box-plots statistics of these simulations are compared with that of the second test series of Grabner (2013). As input parameters for the stochastic-mechanical model are only available for screws with d = 8 mm, ratios are used. Deviating from the general box-plots, the whiskers of the simulated data correspond to the 5%- and 95%-quantiles calculated according to rank statistics, with 5%-quantiles marked as (×). In addition to the box-plots, 95%-confidence intervals (CIs) of mean ratios based on t-tests with CIs according to Fieller calculated in R (2013) are provided. These CIs are only approximate as the test was originally developed for mutually independent normal variables. It is proven that test statistic from logarithmized data does not show any noticeable differences.

4 Results and discussion

Results and discussion are presented in context with associated literature. Section 3.1 aims at statistics for parameters of the load–displacement model in Sect. 2.2; data sets are combined to increase the power in statistical inference. The multivariate approach is defined in Sect. 3.2 and validated in Sect. 3.3.

4.1 Series I: statistical analysis and definition of parameter settings

4.1.1 General data analysis

Table 2 presents the main statistics of density, withdrawal capacity and stiffness for each layer and α separately. An increase in withdrawal properties with increasing α can be observed. This is a well-known circumstance, which has already been anchored in EN 1995-1-1 (2008) and in technical approvals for self-tapping screws. Furthermore, withdrawal properties determined from tests in different layers but comparable density show no significant differences. Thus, a certain amount of locking effect, caused by transversely oriented neighbouring layers, cannot be confirmed in the tested layups with layer thicknesses of 20 and 40 mm and the screw diameter used.

Focusing on the density, currently used as the only indicating material parameter for the withdrawal properties, average values between 430 and 460 kg/m3 can be observed in most sub-series, except for sub-series with α = 90° in layers TL and ML. In these two data sets, on average a significantly lower density is given and in layers CL with α = 45°, 60° and 90° which show on average significantly different densities. The same data sets of CL but also with α = 30° reflect unexpected high coefficients of variation in density with CV[ρ12] = 14–17% (E[CV[ρ12]] = 6–10%, see Brandner 2013b). The different layer thicknesses of TL and ML vs. CL together with deviating densities indicate raw material from different proveniences and / or from different cross-sectional regions within the log (juvenile vs. adult timber).

Pairwise comparisons between average values and between medians of model parameters (F max, k ser, Δw lin, Δw f and c) at given α but different layers reflected significant differences in sub-sets with different densities. Thus, to reduce possible influences caused by different material qualities of CL on the inferred withdrawal parameters, the data of CL is excluded from further processing; the data of TL and ML are combined, see Table 3.

4.1.2 Density correction and representative distribution models

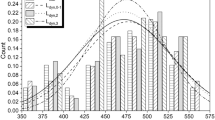

To find adequate corrections for the influence of density on the withdrawal parameters, simple regression analyses were performed. In doing so, the representative marginal distributions of the independent and dependent variables were considered. Therefore, tests on normal (ND) and lognormal (2pLND) distribution were applied for each parameter X = (ρ12, F max, k ser, Δw lin, Δw f and c) and for each thread-fibre angle α = 0°, 30°, 45°, 60° and 90° separately.

Overall, the hypothesis of lognormality was rejected in much less cases than that of normality. In two-thirds of all tests the realized significance for 2pLND was higher than for ND, indicating rather lognormal than normal distributed data. Consequently, and because of physical reasons, (properties of a highly hierarchical material, which is additionally restricted to the positive domain ℝ+, see Brandner 2013b) 2pLND is preferred for parameters ρ12, F max and k ser. 2pLND is also used for parameters Δw lin, Δw f and c due to its simplicity and because the outcome of the tests is unclear.

With 2pLND as marginal distribution, the relationships between (F max, k ser, Δw lin, Δw f and c) and ρ12 were investigated by means of simple power regression analyses with

Simple instead of multiple regression analyses were undertaken to allow regression parameters to be judged set by set. Firstly, this is because, although the data sets of TL and ML are combined the samples are still small. Secondly, the array of ρ12 in the present data with 380 to 520 kg/m3 restricts the inference of global relationships. Thirdly, Ringhofer et al. (2014) observed that relationships between withdrawal parameters and ρ12 may change discontinuously with the changing thread-fibre angle.

As expected, a highly significant and positive relationship between F max and k ser vs. ρ12, is observed, the exceptions being F max,0 and k ser,90. The reduced significance in F max,0 vs. ρ12 has already been mentioned in Ringhofer et al. (2014) and implicitly demonstrated in Pirnbacher et al. (2009). This circumstance is dedicated to changes in the associated failure planes in shear, from RL | RT (corresponding shear strengths f v,RT | f v,RL) or TL | TR (f v,TR | f v,TL) at α = 90° to primary LR | LT (f v,LT | f v,LR) at α = 0°, with LR, LT, RT as vectors of failure planes in longitudinal-radial, longitudinal-tangential and radial-tangential direction, respectively, see Fig. 3. Besides \(\Delta {w_{\text{f}}}\left| {\alpha \;=\;0^\circ \; \cup \;60^\circ } \right.\) there were no significant results found in the regression analysis for parameters c, Δw lin and Δw f. The gradients k [see Eq. (7)] are overall negative, indicating a stiffer and more brittle withdrawal behaviour with increasing density, a circumstance which is in line with experimental observations.

To correct the parameters X = (F max, k ser, c, Δw lin, Δw f) in respect to density by the power model

parameter k X was determined by averaging k X | α, for α = (0°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 90°). The outcome in respect to X is given as k X = (1.40, 1.42, −0.66, −0.19, −0.43). Based on the test results, a reference density ρ12,ref of 440 kg/m3 is used.

The exponents k X found in the analysis are considerably different from those given in Blaß et al. (2006) who proposed 0.8, 0.2 and 0.5 for the correction of F max, k ser and Δw f. A comparable exponent for F max can be found, for example, in Blaß and Uibel (2007). However, Newlin and Gahagan (1938, 1.5), McLain (1997, 1.77–1.35), Soltis (1999, 2.0–1.5), Schneider (1999, 1.78) and Hübner (2013, 1.6) found exponents in the range of 1.35–2.0 for the withdrawal strength f ax = F max / (d π l ef). A comprehensive summary for soft- and hardwoods can be found in Hübner (2013).

The correction of density, which reduces the variability in withdrawal parameters, is made to improve the estimates for the average (mean) relationships between withdrawal parameters and α. However, estimates for the coefficients of variation (CV) are still based on uncorrected (observed) data sets as far as the variability in density is within the expected range of 6–10% (Brandner 2013b); this is fulfilled for all thread-fibre angles of the combined data set TL and ML.

4.1.3 Relationships between withdrawal properties and α

Now the relationships between the current withdrawal properties and model parameters vs. α are of interest. Previous investigations focused on the relationship withdrawal strength f ax vs. α and their proposed models are either a modification of Hankinson’s approach (1921) (Pirnbacher et al. 2009; Blaß et al. 2006; Blaß and Uibel 2007) or a bi-linear relationship (Pirnbacher and Schickhofer 2007; Hübner 2013). Overall, an approximately constant f ax | α ≥ (30°) 45° followed by a subsequent decrease at α ≤ (30°) 45° can be concluded. For characterization of the withdrawal capacity, the ratio between the withdrawal strengths at α = 90° and 0°,

is commonly used.

This information is now used in analysing the relationships of all model parameters in Eq. (1) vs. α by applying three approaches: (1) the Hankinson approach, see Eq. (7), (2) a bi-linear approach with a fixed anchor-point at α = 45°, see Eq. (8), and (3) a polynomial approach of third order, see Eq. (9).

The outcome, based on non-linear least-squares method, is visualized in Fig. 4 and quantified in Table 4.

A significantly reduced variability caused by density correction in all data sets of parameters with a significant relationship to density, F max and k ser, is observed. The medians are not influenced so far. ρ12,mean of the uncorrected (observed) data set was approximately equal to the reference density. The significantly lower density at α = 90° causes a shift in the medians.

The average withdrawal capacity F max,mean | α = 0° and 90° is significantly lower and higher, respectively, than F max,mean | 30° ≤ α ≤ 60°, whereas no significant differences are found between means and medians of log(F max) | 30° ≤ α ≤ 60°. The approach of Hankinson and the bi-linear model allow only a rough approximation of the relationship F max vs. α. The ratio k 90,mean = 1.45 is higher than in Blaß et al. (2006) and Blaß and Uibel (2007). Ringhofer et al. (2014) reported a dependency of k 90 on density as a consequence of changing failure planes considering withdrawal at α = 0° and 90°. Their analysis, based on Pirnbacher et al. (2009), estimates k 90,mean | ρ12,mean = 440 kg/m3 with 1.37, being not far from the current value. Although not generally considered, there is a sigmoid course in F max vs. α with a second increase in withdrawal capacity from α = 60° to 90°, a circumstance which can also be found in the data of Pirnbacher et al. (2009), Hübner (2013) and Blaß et al. (2006). The bi-linear approach in Fig. 4 overestimates F max | 0° < α < 90°; a calibration to F max | α = 60° would motivate a constant branch within 30° ≤ α ≤ 90°, however, the resistance at α = 90° would be significantly underestimated. The Hankinson’s approach, although commonly used and anchored in EN 1995-1-1 (2008), does not provide an inflexion point with a constant plateau within 30° ≤ α ≤ 60°. Thus the polynomial approach is used further.

The relationship k ser vs. α shows a significant reduction in medians from α = 0° to 30° and from 45° to 60°. This course is again attributed to changing failure planes in withdrawal, see Fig. 4. For example, the transition from LR to LT and reverse at α ≈ 45° is already well known for solid timber (see e.g. Denzler and Glos 2007; Brandner et al. 2012). In the case of withdrawal and changing thread-fibre angles from 0° to 90°, there is a transition from LR and LT to primary TL and RT (side boards) or, more infrequently, to RL and RT (rift boards). Rolling shear causes resistances in TL and RL to be lower than those in TR and RT planes, which are exposed to transverse shear. The bi-linear model, as the simplest model for the description of k ser vs. α, is used further. The comparison of both relationships, F max and k ser vs. α, shows that they are not only inverse but also different. This indicates that mechanisms relevant at the maximum load may be different from that relevant at the apparent linear-elastic part of the load–displacement curve.

The bi-linear approach is preferred for the relationship Δw lin vs. α. This decision is supported by highly significant different medians at α = 0°, 30° and 45°, determined by pairwise Mann–Whitney U tests, whereas the hypothesis of equal medians at 45°, 60° and 90° cannot be rejected. The modified Hankinson approach failed because of a lack of flexibility. The polynomial approach was excluded because of its higher complexity but equal goodness of fit.

Over the course of Δw f vs. α, a sharp and regressive decrease from α = 90° to 0° is noticed, with highly significant differences in the pairwise comparison of medians between 0°, 30°; 30°, 45° and 60°, 90°. The polynomial approach is identified as a representative model.

Comparable to F ax vs. α, in the course of c vs. α a constant plateau between 30° ≤ α ≤ 60° is observed, as are significantly different medians (and averages of logarithmised data) for α = 0° and 30° and α ≤ 60° and 90°. This provides additional motivation for the polynomial approach being first choice.

4.1.4 Correlations between model parameters

Now the correlation between parameters X = (ρ12, F max, k ser, c, Δw lin, Δw f) is of interest. The determination of adequate measures of correlation is in general a challenging task. However, in respect to 2pLND as representative distribution model and the definition of Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the normal domain, the correlations are analysed for the logarithmised data set and compared with Spearman’s parameter free rank correlation coefficient. Due to different and partly reverse relationships of variables X at the extremes of α, inference is made separately for each α. The outcomes are tested on significant differences, their physical plausibility proven and remaining statistics of correlations averaged, see Table 5. As expected, a highly significant correlation is found between ln(F max) and ln(ρ12), apart from α = 0°. Furthermore, a positive correlation between ln(F max), ln(k ser) and ln(ρ12) at a fixed α is expected as the screws are anchored in a denser material. For a given α a positive relationship between ln(F max) and ln(k ser) is also confirmed.

A highly significant correlation is found also between ln(c) and ln(Δw f). This is supported by comparable gradients in the softening zone. The positive relationship between ln(Δw lin) and ln(c) follows the same argument.

A significantly negative correlation is observed between ln(k ser) and ln(Δw f) and ln(Δw lin). Withdrawal tests show a positive correlation between stiffness and the tendency to more brittle failures in combination with a reduced plastic (non-linear) zone. In principle, the same circumstances apply for ln(F max) and ln(ρ12) vs. ln(Δw lin) and ln(Δw f). Due to the highly significant positive relationship between ln(F max) and ln(ρ12) and ln(k ser), the negative relationships to ln(Δw lin) and ln(Δw f) are not that distinctive. These relationships also necessitate a negative correlation between ln(c) and ln(ρ12), ln(F max) and ln(k ser). This is because the gradient in the softening zone increases absolutely with increasing brittleness and decreasing plasticity (non-linearity). Concerning the correlation between ln(Δw lin) and ln(Δw f), a slightly negative relationship is found, argued by the same circumstance that higher values of Δw f coincide with lower resistance and stiffness but higher non-linearity in the load–displacement curve, leading overall to a decrease in Δw lin.

Overall, the correlations of Pearson and Spearman are congruent, apart from ln(Δw lin) vs. ln(Δw f). Although a positive correlation is expected and confirmed by Spearman, Pearson’s correlation is negative. As the Pearson correlation matrix is in addition not positive definite, a prerequisite for its later use in multivariate modelling, r(ln(Δw lin); ln(Δw f)) is set to 0.10.

4.2 Multivariate model approach

Within Sect. 3.1 the main statistics, distribution models and correlations for the load–displacement model parameters in Sect. 2.2 and their relationships to α were determined. This information is now used for defining the multivariate model approach, which allows a complete stochastic characterisation of single screw’s withdrawal properties.

Based on lognormal distributed variables X = (F max, k ser, c, Δw lin, Δw f)t, the transformation Y = ln(X) makes it possible to operate with a multivariate normal distribution (MVND)

in the logarithmic domain, with μ Y and \({\varvec{\Sigma}}\) Y as expectation vector of dimension \(1 \times 5\) (equal to the dimension of X) and covariance matrix of dimension \(5 \times 5\), respectively. The expected values for μ Y are estimated from the density corrected data, with X mean,90 = (10,842; 11,994; 5.25; 0.33; 2.56), X mean,0 = (7487; 16,958; 2.32; 0.23; 0.70) and k 90, X = X mean,90 / X mean,0 = (1.45; 0.71; 2.27; 1.41; 3.65). The variances are estimated by averaging the statistics of observed data, with CV[X] = (13, 16, 25, 25, 12)%. The covariances are based on the estimates for Pearson’s correlation coefficient in Table 5. Figure 5 visualises the average load–displacement curves for α = 0° and 90°. Whereas the load–displacement curves at α = 0° and 90° in Fig. 5, left are significantly different, for α = 0° has a tendency to be stiffer and more brittle, in a relative view in Fig. 5, right both curves appear more coherent. The distinct softening before F max,0 is not self-evident considering that timber fails normally rather brittle in longitudinal shear. Reasons for the non-linear load–displacement behaviour are (1) the non-linear stress distribution along the screw axis, (2) the inhomogeneous material, and (3) differences in shear properties of LR and LT shear planes. The first two reasons forward the redistribution of stresses along the screw axis after local resistances have been exceeded. The even more pronounced softening before F max given α = 90° is additionally dedicated to the typical non-linear material behaviour of timber before failing in transverse and rolling shear, together with the interaction of both stress fields around the perimeter of the screw. These reasons, together with the significantly different strength and stiffness properties in longitudinal, transverse and rolling shear, provoke the reverse relationships of F max and k ser vs. α. The k 90 factor of F max corresponds approximately to the reciprocal k 90 factor of k ser.

Applying this multivariate model approach based on the given parameter setting, variates were generated in R (2013) by using the eigenvalue decomposition. These variates are used to generate virtual load–displacement curves; this by discretizing the displacement comparable to the frequency in data recording during testing, with a displacement-increment of 0.002 mm, with w ini = 0 and for a data frame of w = (0, 10) mm. The curves were modelled until 40% load-drop from F max in the softening domain (w > w f).

Load–displacement curves of single screws positioned between different layers, for example in case of gaps, are generated by considering the parallel system action with uniform load-redistribution after partial failures, i.e. by summing up simulated load–displacement data of single screws, generated for specific α and balanced by their share of contribution.

For modelling the influence of gap type and width (see Fig. 1) on the withdrawal properties, the residual lateral areas were calculated as

and

Values for the (residual) circumference (U res) U together with details and definitions for both gap types are summarized in Fig. 6.

4.3 Series II: statistical analysis and model verification

4.3.1 General data analysis

Table 6 shows the main statistics of density, k ser and F max, differentiated in respect to the type and width of gaps as well as the screw diameter. All withdrawal tests in TL, CL and ML were made with α = 0°. The data comprises tests accomplished in the centre of a lamella (no gap, solid timber; ST) and between two lamellas (butt joint; BuJ) with gap widths of w gap = 0, 2 and 6 mm (BuJ0, BuJ2 and BuJ6, respectively). To improve the statistical power, the data from TL, CL and ML, given a certain type of gap, was combined. Any possible influences on withdrawal properties caused by differences in density are compensated by applying density correction according to Eq. (8) and by using the exponents found in the current analysis (see Table 6).

Withdrawal tests accomplished in the intermediate layer (IL) make it possible to analyse the influence on the withdrawal parameters caused by the interaction of α = 0° and 90°. The data comprises tests in bed joints (BeJs) and T-joints (TJs), the second type again with w gap = 0, 2 and 6 mm (TJ0, TJ2 and TJ6, respectively).

Although mean densities of different CLT layers at equal gap type are well comparable, the mean densities of different gap types (see Table 6) are in some cases quite different. A possible reason is the insufficient precession in predrilling, in particular in cases of w gap = 6 mm, considering drill diameters of 5 and 7 mm for d = 8 and 12 mm, respectively. This may cause some bias in calculated density in cases where the theoretically calculated loss in material due to pre-drilling is not equivalent to the practical execution. This may also cause some bias in density corrections of k ser and F max, applied later. However, this influence is judged to be small.

4.3.2 Model validation

For validation of the multivariate model approach, developed for the description of the load–displacement behaviour of screws tested in withdrawal using multivariate input parameters, the influence of gap types and widths on the withdrawal parameters k ser and F max are analysed and their distributions are compared based on tests with simulated data. Beforehand, the expectations are briefly outlined which are based on general investigations on stochastic-mechanical systems in Brandner (2013b):

-

BuJ0 vs. ST | α = 0°: for k ser, equivalence of mean values k ser,mean | BuJ0 ≈ k ser,0,mean together with a significant reduction in dispersion, with CV[k ser | BuJ0] ≈ CV[k ser,0] / √2, is expected. Due to the non-linear load–displacement behaviour before and after F max, there is a high potential for load-redistribution after partial failures, i.e. after exceeding the capacity of the screw in one layer or lamella. In comparison to F max,0, thus only a slightly lower F max,mean | BuJ0 is expected together with significantly reduced CV[F max | BuJ0] ≥ CV[F max,0] / √2.

In fact, averaging all stiffness values from independently and identically distributed (iid) commonly parallel acting system components together with reduced CV[k ser] is a general outcome of the stochastic-mechanical model of parallel acting linear-elastic springs. Hereby, both statistics follow approximately the distribution of mean values, with

with E[.] as expectation value and N → ∞ as the number of variables X. The averaging of stiffness properties in the linear-elastic zone is also valid for all other investigated types of closed gaps and is explicitly implemented in the stochastic-mechanical multivariate model approach.

-

BeJ0 vs. ST | α = 0°: due to the anchorage of the screw to 50% perpendicular to grain, F max,mean | BeJ0 higher than F max,0,mean is expected. However, because of the reverse relationships of F max and k ser vs. α, F max,mean | BeJ0 will be closer to F max,0,mean than to F max,90,mean. Also, a reduced CV[F max | BeJ0] is expected.

-

TJ0 vs. ST | α = 0°: because of the interaction 0°|90°|0° it is assumed that F max,mean | TJ0 ≤ F max,mean | BeJ0, and CV[F max | TJ0] slightly reduced.

-

BuJ0 vs. BuJ2 and BuJ6: it is expected an approximately continuous decreasing F max,mean, proportional to the loss of lateral area of the screw, without influence on CV[F max].

-

TJ0 vs. TJ2 and TJ6: increasing gap width comes along with decreasing shares of α = 0°. This, together with the loss of volume for anchoring, leads to a decrease in k ser,mean higher than in F max,mean. This is again motivated by the reverse relationship of both properties in respect to α. However, for each property the decrease will be proportional to the loss of lateral area within α = 0°. Thus, a minor raise of CV[F max] is also expected.

With these expectations the validation of the model is now the focus. A summary of the main statistics for screw diameter d = 8 mm is provided in Table 7.

A direct confrontation of test and simulation data is provided via box-plots in Fig. 7. Regarding the expectations outlined before, analysing and comparing Tables 6 and 7 and Fig. 7 led to the following observations: overall, a good to very good agreement between expectations and simulations as well as between the distributions of test and simulation data is observed. Variations in test data, in particular from tests conducted in gaps, are higher than in simulations. This is due to the uncertainties induced by placing screws in gaps, even if they are closed and the screw holes pre-drilled.

However, remarkable deviations occur between tests and simulations of TJs. Consultation with the staff performing the tests confirmed that, in particular for screws with diameter d = 8 mm, exact positioning was not possible despite pre-drilling. As the resistance against screwing is larger for α = 90°, the test data conforms more to BuJs than to TJs, especially for w gap = 6 mm. Therefore, box-plots of simulation data are split in half; the left side corresponds to X / X mean | TJ0 and the right side to X | BuJ>0 / X mean | TJ0. Even then, large deviations between the distributions of k ser | TJ>0 from tests and simulations (d = 8 mm) are observed. The reason for this is the unrealistically high reference value k ser,mean | TJ0, which is comparable to k ser,0,mean. A new reference value, estimated by using k ser,0,mean from tests and k 90 | k ser = 0.71 from the model input parameters, yields 15.8 kN/mm and allows for much better agreement with simulations. There is also a significant difference between F max,0,mean and F max,mean | BuJ0 for both test series, d = 8 and 12 mm, whereas the hypotheses of equivalent medians cannot be rejected for d = 8 mm. However, a minor reduced mean value was expected for BuJs, due to the parallel interaction of two iid shares. As the mean values before density correction are nearly comparable, the magnitude of decrease in series d = 12 mm may also be caused by uncertainties in determinations and / or correction of densities.

Regarding k ser, the partial deviation of results is of particular interest. After all, the stochastic-mechanical multivariate model approach used for the simulations has explicitly implemented the averaging of stiffness values from all interacting load–displacement curves. This deviation seems to be caused by the uncertainties in measuring local deformations of screws tested in withdrawal, a circumstance which is also indicated by CV[k ser] larger than CV[F max]. However, as a second important part of the model, a loss in resistance and stiffness proportional to the decrease in lateral area of anchorage given w gap > 0 is assumed. Overall, good agreement between model and test data in Fig. 7 already reveals the validity of this assumptions as simplifications. A comparison of mean-ratios of test data from BuJs with the percentages in Fig. 6 again validates the assumptions made.

5 Conclusion

A stochastic-mechanical multivariate model approach was established describing the load–displacement behaviour of self-tapping screws by adapting the model developed by Glos (1978). This model facilitates simulating the withdrawal behaviour of axially loaded self-tapping screws in the narrow face of CLT in dependence of α and the positioning of screws in respect to gaps. Additionally, power regression models for density correction of all withdrawal model parameters are provided.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report on a probabilistic model for the withdrawal behaviour of axially loaded self-tapping screws in general. A previously unrecognized factor in modelling the load–displacement behaviour of single fasteners, softening, was realized as part of the model. The approach was successfully validated by comparing the model outcome, analysing the influence of gaps and interacting layers with different α.

Unlike previous studies (e.g. Blaß and Uibel 2007), this study here identified a much higher significant influence of α on the withdrawal capacity, comparable with Ringhofer et al. (2014). Despite the findings of Blaß and Uibel (2007), the authors report on the first study which explicitly quantifies the influence of gaps in interacting layers of different α on the withdrawal behaviour of self-tapping screws. This model makes it possible to investigate (1) the withdrawal capacity, (2) the initial stiffness, (3) the stiffness dedicated to the maximum load, (4) the deformation at maximum load, and (5) the deformation at 60% of F max | w ≥ w f in the softening zone. The model also includes the ability to consider slip and / or delayed stiffening, a characteristic typical for hierarchically structured natural materials also known as J-curve (Gordon 1988).

The inferred model parameters are limited to CLT made of common quality Norway spruce with a density of 380–520 kg/m3, self-tapping screws from one manufacturer, of one diameter and of one effective length. However, the limitations in data basis are not automatically limitations of the probabilistic model. For example, Pirnbacher and Schickhofer (2007) report on a comparative study between eight different types of screws, focusing on withdrawal strength. Apart from the differences caused by the handling of the screws, no significant differences in withdrawal strength were found. Quantification of influences caused by the effective length, nominal screw diameters and their relation to the withdrawal parameters can be done according to models from previous studies (e.g. Blaß et al. 2006; Pirnbacher et al. 2010; Ringhofer et al. 2015) at least for withdrawal strength and stiffness. The present study only focuses on withdrawal failures of single screws. However, apart from block shear and head-pull through failure, the uncertainties in withdrawal are largest. The comparison of test and simulation data reveals the high potential of stochastic-mechanical models which allow the whole distribution of parameters to be estimated, and not only the average; this with minimum effort, time and costs. The inferred parameters are based on homogeneous CLT, i.e. composed of layers of equal strength class. However, as long as the relationships between model parameters and density are also verified for a larger bandwidth, this approach can easily be applied to modelling the withdrawal in heterogeneous CLT, i.e. with layers of different strength classes and / or timber species, insofar as density as parameter, currently the only indicating timber property, is still valid. The confrontation of test and simulation data also explicitly outlines inadequateness in test execution, in particular considering the data of T-joints. Apart from this, the results clearly show the remarkable impact of gaps on attainable withdrawal properties. Current CLT productions aim to minimize gaps and gap widths even within cross layers; nevertheless, insertion of screws in open gaps cannot be excluded. For practical applications, the following is suggested:

-

Application of screws with d ≥ 8 mm; the screw diameter should be significantly larger than the maximum gap width currently allowed in technical approvals for CLT, i.e. w gap ≤ 6 mm;

-

T-joints should be conservatively treated as butt-joints; secure positioning of screws in open T-joints even in pre-drilled holes is not possible, in particular for smaller screw diameters;

-

Screws should be positioned inclined parallel to the CLT side face at α = 30° to 60° and, if possible, also perpendicular to the side face at α ≥ 10°; inclined positioning minimizes the influence of gaps on withdrawal parameters as long as the load-bearing penetration length of screws in timber is sufficient (see e.g. Blaß and Uibel 2009).

The presented multivariate model approach is seen as a worthwhile basis for investigations into the withdrawal behaviour of axially loaded groups of screws positioned in the narrow face of CLT and subjected to withdrawal failure but this is beyond the scope of this contribution. There is great potential for such applications regarding the development of CLT system connectors as an innovative step forward to an adequate connection system for the solid timber construction technique with CLT in general. Here, the ability to introduce locally concentrated loads of high magnitude is a prerequisite. Compliance with regulations on the minimum spacing and edge distances is thereby supposed. There is definitely a need to define regulations for screws positioned in layers of different α and for the influence of gaps. Concerning gaps it is intended to establish a probabilistic approach for judging their influence in case of industrially produced CLT featuring randomly distributed gap widths and, in respect to the layup of CLT, for randomly positioned fasteners. The aim is to report on this subject elsewhere.

References

Attiogbe E, Morris G (1991) Moment-rotation functions for steel connections. J Struct Eng 117(6):1703–1718

Blaß HJ (1991) Traglastberechnungen von Nagelverbindungen [Characteristic strength of nailed joints]. Holz Roh-Werkst 49:91–98 (in German)

Blaß HJ, Uibel T (2007) Tragfähigkeit von stiftförmigen Verbindungsmitteln in Brettsperrholz [Load-bearing capacity of dowel-type fasteners in cross laminated timber]. Karlsruher Berichte zum Ingenieurholzbau 8, Lehrstuhl für Ingenieurholzbau und Baukonstruktionen, Universität Karlsruhe (TH), ISBN 9783866441293, pp 204 (in German)

Blaß HJ, Uibel T (2009) Bemessungsvorschläge für Verbindungsmittel in Brettsperrholz [Design proposals for fasteners in cross laminated timber]. Bauen mit Holz 111(2):46–53 (in German)

Blaß HJ, Bejtka I, Uibel T (2006) Tragfähigkeit von Verbindungen mit selbstbohrenden Holzschrauben mit Vollgewinde [Resistance of joints with self-tapping fully-threaded timber screws]. Karlsruher Berichte zum Ingenieurholzbau 4, Lehrstuhl für Ingenieurholzbau und Baukonstruktionen, Universität Karlsruhe (TH), ISBN 3866440340, pp 220 (in German)

Brandner R (2013a) Production and Technology of Cross Laminated Timber (CLT): A state-of-the-art Report. In: R Harries, A Ringhofer, G Schickhofer (ed.) Focus solid timber solutions—European conference on cross laminated timber (CLT), Graz University of Technology, COST Action FP1004, ISBN 1-85790-181-9

Brandner R (2013b) Stochastic system actions and effects in engineered timber products and structures. Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz, ISBN 978-3-85125-263-7

Brandner R, Gatternig W, Schickhofer G (2012) Determination of Shear Strength of Structural and Glued Laminated Timber. CIB-W18/45-12-2, Växjö, Sweden

Denzler JK, Glos P (2007) Determination of shear strength values according to EN 408. Mater Struct 40:79–86

EN 13183 (2002) Moisture content of a piece of sawn timber—part 1: determination by oven dry method. European Committee for Standardization (CEN)

EN 1382 (1999) Timber structures—test methods—withdrawal capacity of timber fasteners. European Committee for Standardization (CEN)

EN 1995-1-1 (2008) +A1 Eurocode 5: design of timber structures—part 1–1: general—common rules and rules for buildings. European Committee for Standardization (CEN)

EN 26891 (1991) Timber structures—joints made with mechanical fasteners—general principles for the determination of strength and deformation characteristics. European Committee for Standardization (CEN)

EN 338 (2009) Structural timber—strength classes. European Committee for Standardization (CEN)

ETA-11/0190 (2011) European Technical Approval, Self-tapping screws for use in timber constructions. Adolf Würth GmbH and Co. KG

Flatscher G (2014) Beschreibung der Last-Verschiebungskurven von Verbindungen im Holzbau [Description of load-displacement curves of joints in timber engineering]. In: Kuhlmann U (ed) Doktorandenkolloquium “Holzbau Forschungs + Praxis”, pp 147–155, Stuttgart, Germany

Foschi RO (1974) Load-slip characteristics of nails. Wood Sci 7(1):69–76

Glos P (1978) Zur Bestimmung des Festigkeitsverhaltens von Brettschichtholz bei Druckbeanspruchung aus Werkstoff- und Einwirkungskenngrößen [For the determination of compression strength of glulam in relation to characteristics of material and exposure]. Berichte zur Zuverlässigkeit der Bauwerke 35, Sonderforschungsbereich 96, Laboratorium für den Konstruktiven Ingenieurbau (LKI), Technische Universität München (in German)

Gollwitzer S (1986) Zuverlässigkeit redundanter Tragsysteme bei geometrischer und stofflicher Nichtlinearität [Reliability of redundant structural systems given geometrical and material non-linearity]. Dissertation, Institut für Bauingenieurwesen III, Lehrstuhl für Massivbau, Technische Universität München, p 215 (in German)

Gollwitzer S, Rackwitz R (1990) On the reliability of Daniels systems. Struct Saf 7:229–243

Gordon JE (1988) The science of structures and materials. Scientific American Books Inc., Scientific American Library, ISBN 0-7167-5022-8

Grabner M (2013) Einflussparameter auf den Ausziehwiderstand selbstbohrender Holzschrauben in BSP-Schmalflächen [Influencing effects on the withdrawal resistance of self-tapping screws in the narrow faces of CLT]. Master thesis, Graz University of Technology (in German)

Hankinson RL (1921) Investigation of crushing strength of spruce at varying angles of grain. US Air Service Information Circular, Vol. 3, No. 259, Washington DC, US Air Service, Materials Section Paper No. 130

Hübner U (2013) Mechanische Kenngrößen von Buchen-, Eschen- und Robinienholz für lastabtragende Bauteile [Mechanical properties of beech, ash and black locust for load-bearing components]. Dissertation, Institute of Timber Engineering and Wood Technology, Graz University of Technology (in German)

ISO 3131 (1975) Wood—determination of density for physical and mechanical tests. International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

Jaspart JP (1991) Etude de la semi-rigidite des noeuds poutre-colonne et son influence sur la resistance et la stabilite des ossatures en acier [Study of the semi-rigidity of the beam-column nodes and its influence on the strength and stability of steel frames]. Dissertation, Faculte des Sciences Appliquees, Universite de Liege, pp 563 (in French)

Lane T (2014) The rise of cross laminated timber. Building.co.uk. http://www.building.co.uk/the-rise-of-cross-laminated-timber/5069291.article. Accessed 02 June 2016

McLain TE (1997) Design axial withdrawal strength from wood: I. Wood screws and lag screws. For Prod J 47(5):77–84

Newlin JA, Gahagan JM (1938) Lag-screw joints: their behaviour and Design. United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. Technical Bullet No. 597

Pirnbacher G, Schickhofer G (2007) Schrauben im Vergleich – eine empirische Betrachtung [Comparison of screws – an empirical examination]. 6. Grazer Holzbau-Fachtagung (6.GraHFT’07) “Verbindungstechnik im Ingenieurholzbau”, Graz, Austria, F-1–22 (in German)

Pirnbacher G, Brandner R, Schickhofer G (2009) Base parameters of self-tapping screws. International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction—Working Commission W18—Timber Structure, CIB-W18:42-7-1. Dübendorf, Switzerland

R Core Team (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://www.R-project.org/

Reichelt B (2012) Einfluss der Sperrwirkung auf den Ausziehwiderstand selbstbohrender Holzschrauben. Eine vergleichende Betrachtung zwischen BSP und BSH [Influence of the cross effect on the withdrawal resistance of self-tapping screws]. Master thesis, Graz University of Technology (in German)

Richard RM, Abbott BJ (1975) Versatile elastic-plastic stress-strain formula. J Engrg Mech Div, ASCE 101(4):511–515

Ringhofer A, Brandner R, Grabner M, Schickhofer G (2014) Die Ausziehfestigkeit selbstbohrender Holzschrauben in geschichteten Holzprodukten [The withdrawal strength of self-tapping timber screws in laminated timber products]. Doktorandenkolloquium Holzbau—Forschung und Praxis, Stuttgart, Germany (in German)

Ringhofer A, Brandner R, Schickhofer G (2015) A Universal Approach for withdrawal properties of self-tapping screws in solid timber and laminated timber products. In: 2nd Meeting of the International Network on Timber Engineering Research (INTER), 48-7-1, Sibenik, Croatia

Schneider P (1999) Auszugsfestigkeit von EJOT-Rahmenschrauben [Withdrawal strength of EJOT screws]. Research Report, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) Zürich (in German)

Silva CV, Ringhofer A, Branco J, Schickhofer G (2014) The influence of moisture content and gaps on the withdrawal resistance of self tapping screws in CLT. CNME 2014—congresso nacional de mecânica experimental, Aveiro, Portugal

Soltis LA (1999) Wood handbook – Wood as an engineering material. Chapt. Fastenings, pp 7–1 to 7–29, Madison, WI: U.S.: United States Government Printing, 1999 (USDA Agricultural Handbook General technical report FPLGTR-113)

Statistisches Bundesamt (2016) Statistiken Zimmerei und Holzbau 2016 [Statistics of carpentry and timber engineering 2016]. Holzbau Deutschland—Bund Deutscher Zimmermeister im Zentralverband des Deutschen Baugewerbes, pp 4

Teischinger A, Stingl R, Zukal LM (2011) Holzbauanteil in Österreich: Statistische Erhebung von Hochbauvorhaben [Share of timber structures in Austria: statistical evaluation of building constructions]. Zuschnitt Attachment—Sonderthemen im Bereich Holz, Holzwerkstoff und Holzbau, proHolz Austria, ISBN 978-3-902320-84-1

Z-9.1-514 (2011) Allgemeine bauaufsichtliche Zulasssung, Würth ECOFAST-ASSY II und Würth ECOFAST-ASSY II Holzschrauben als Holzverbindungsmittel [General technical approval, Würth ECOFAST-ASSY II and Würth ECOFAST-ASSY II timber screws as timber fasteners]. Adolf Würth GmbH and Co. KG (in German)

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Graz University of Technology. This research work is financed by the Institute of Timber Engineering and Wood Technology at the Graz University of Technology and performed in collaboration with the competence centre holz.bau forschungs gmbh and partners from industry involved in the COMET K-Project “focus_sts”. This project is financed by funds provided by the Federal Ministry of Economics, Family and Youth, the Federal Ministry of Transport, Innovation and Technology, the Styrian Business Promotion Agency Association and the province of Styria (A14).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Brandner, R., Ringhofer, A. & Grabner, M. Probabilistic models for the withdrawal behavior of single self-tapping screws in the narrow face of cross laminated timber (CLT). Eur. J. Wood Prod. 76, 13–30 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-017-1226-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-017-1226-3