Abstract

A new method was developed to reproduce the tsunami height distribution in and around the source area, at a certain time, from a large number of ocean bottom pressure sensors, without information on an earthquake source. A dense cabled observation network called S-NET, which consists of 150 ocean bottom pressure sensors, was installed recently along a wide portion of the seafloor off Kanto, Tohoku, and Hokkaido in Japan. However, in the source area, the ocean bottom pressure sensors cannot observe directly an initial ocean surface displacement. Therefore, we developed the new method. The method was tested and functioned well for a synthetic tsunami from a simple rectangular fault with an ocean bottom pressure sensor network using 10 arc-min, or 20 km, intervals. For a test case that is more realistic, ocean bottom pressure sensors with 15 arc-min intervals along the north–south direction and sensors with 30 arc-min intervals along the east–west direction were used. In the test case, the method also functioned well enough to reproduce the tsunami height field in general. These results indicated that the method could be used for tsunami early warning by estimating the tsunami height field just after a great earthquake without the need for earthquake source information.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

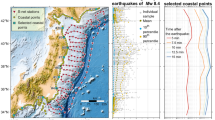

The 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake (M w9.1) generated enormous tsunamis that caused devastation along the Pacific coast of the Tohoku region of Japan (Mori et al. 2012). Although the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) issued tsunami early warning messages and forecasts on tsunami heights along the coast of Japan (Ozaki 2011), approximately 18,000 people were killed by the tsunami. Consequently, establishing a tsunami warning system, which is more accurate and rapid, has become an urgent issue in Japan. In 2011, the National Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience in Japan started installing a dense cabled observation network, called the Seafloor Observation Network for Earthquakes and Tsunamis along the Japan Trench (S-NET). This network consists of 150 ocean bottom pressure gauges (Uehira et al. 2012; Kanazawa 2013). The ocean bottom pressure gauges in the S-NET are connected at 30 km intervals by a cable and the network is distributed along a wide portion of the seafloor off Kanto, Tohoku, and Hokkaido as shown in Fig. 1.

Map of a dense cabled observation network called the Seafloor Observation Network for Earthquake and Tsunamis along the Japan Trench (S-NET) (Kanazawa 2013). Red circles show the location of 150 ocean bottom pressure sensors

Tsunami numerical simulations are powerful tools to understand the effects of large tsunamis along the coast and the earthquake source processes or to forecast tsunami heights for tsunami warning purposes. Consequently, such simulations have been used extensively in tsunami research communities (Satake 2015; Geist et al. 2016). In such tsunami simulations, the initial ocean surface displacement is computed typically from the ocean bottom deformation caused by the faulting of a large earthquake (Tanioka and Seno 2001; Gusman et al. 2012), or is assumed the same as the ocean bottom deformation (e.g., Satake et al. 2013). In other instances, the ocean surface displacement can be estimated directly from the observed tsunami waveforms (Tsushima et al. 2012; Saito et al. 2011). Therefore, the initial ocean surface displacement estimated from the seismic, geodetic, or tsunami waveform data is necessary to compute tsunami propagation.

Recently, Maeda et al. (2015) have developed a method to forecast coastal tsunamis by assimilating tsunami observations continuously without information on the initial ocean surface displacement. Gusman et al. (2016) applied this method to the tsunami generated by the 2012 Haida Gwaii earthquake and computed the tsunami wave field successfully by assimilating the tsunami waveforms observed at the ocean bottom pressure gauge network in Cascadia. However, this method is difficult to apply to ocean bottom pressure sensors within the source area, i.e., the deformation area of tsunami generation because the ocean surface displacement above the source area just after the earthquake cannot be observed by the ocean bottom pressure gauges at the source area. The ocean surface displacement is almost the same as the ocean bottom deformation because the wavelength of the deformation is much larger than the ocean depth; therefore, the thickness of the sea water before the earthquake is almost the same as that just after the earthquake (Tsushima et al. 2012).

A tsunami forecast system was developed by Tsushima et al. (2009, 2012) that uses the ocean bottom pressure sensors in and around the source area. This system is called tsunami Forecasting based on Inversion for initial sea-Surface Height (tFISH). As this method estimates the initial sea-surface displacement from the observed tsunami waveforms, it requires a substantially long time for tsunami early warning. Recently, the method was improved using geodetic observations on land as well as the ocean bottom pressure observations to facilitate rapid forecasting (Tsushima et al. 2014; Melgar and Bock 2013). However, such methods continue to estimate the tsunami source from the observations.

In this paper, we developed a new tsunami numerical simulation method, assimilating the pressure data in and around the source area, observed at the ocean bottom pressure gauges, such as those of S-NET, as shown in Fig. 1. As this method estimates the tsunami height distribution at a particular time directly from the observation data, it can be used for tsunami early warning without any earthquake information.

2 Method for Estimation of a Tsunami Height Field

When a tsunami propagates away from the source area, the ocean surface displacement or tsunami height, \(\eta \left( {x,y,t} \right)\), is proportional simply to the pressure change at the ocean bottom, \(\Delta p\left( {x,y,t} \right)\), as shown in Eq. (1). This is because the wavelength of a tsunami caused by a great earthquakes (M > 8.0), > 100 km, is much larger than the ocean depth. This is dictated by the shallow water wave theory.

where ρ is the density of sea water and \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration.

In the source area, where a permanent sea floor deformation is caused by the faulting of a great earthquake, \(B\left( {x,y,t} \right)\) (Fig. 2), the pressure change at the ocean bottom, \(\Delta p\left( {x,y,t} \right)\), is

We defined the water-depth fluctuation, \(h_{\text{f}} \left( {x,y,t} \right)\), which is proportional to the ocean bottom pressure as,

Equation (3) indicates that the ocean surface displacement or tsunami height, \(\eta \left( {x,y,t} \right)\), cannot be calculated without knowledge on the permanent sea floor deformation caused by an earthquake, whereas we observe \(\Delta p\left( {x,y,t} \right)\) at the ocean bottom pressure gauges (see Tsushima et al. 2012). After the earthquake is completed at a time of t 0, \(B\left( {x,y,t} \right)\) is no longer a time dependent and becomes \(\left( {x,y,t_{0} } \right)\) (Fig. 2) as follows

The time derivative of Eq. (4) is

The time derivative of tsunami height, \(\frac{{\partial \eta \left( {x,y,t} \right)}}{\partial t}\), is the same as the time derivative of the water-depth fluctuation which can be obtained from the ocean bottom pressure data, \(\Delta p\left( {x,y,t} \right)\).

For numerical computation of a large tsunami propagated in the deep ocean, generally, the linear long-wave equation is solved. The wave equation of the linear long-wave approximation is

where d is the depth of the ocean.

Using Eqs. (5) and (6), we get

Then, the finite difference equation becomes

where i and j are the indexes of points for x- and y-directions in the computed domain, k is the index for time steps, \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta y\) are the space intervals of x- and y-directions, respectively, and \(\Delta t\) is the time interval.

Here, we assumed that there were ocean bottom pressure sensors at each point, as indicated in Fig. 3. Therefore, the left-hand side of Eq. (8) was obtained from the observed pressure data at the ocean bottom pressure sensors because we defined \(h_{\text{f}}\) as the water-depth fluctuation which is proportional to the ocean bottom pressure. The unknown parameters are the ocean surface displacement field or tsunami height distribution, \(\eta_{i,j}^{k}\), above the ocean bottom pressure gauge network at a particular time (Fig. 3). We have Eq. (8) for each observation point. We assumed that the tsunami heights outside the pressure gauge network were 0. Subsequently, we could compute the tsunami height distribution, \(\eta_{i,j}^{k}\), above the ocean bottom pressure sensor network by solving the following Eqs. (9 or 10) which include Eq. (8) at all the observation points:

Pressure sensor system where the water-depth fluctuation, \(h_{{{\text{f}}_{i,j} }}^{k}\), and tsunami height distribution, \(\eta_{i,j}^{k}\), in Eqs. (8) and (10) are computed. k is an index for time steps

where A is the matrix consisting of coefficients of the right-hand side of Eq. (8), m consists the unknown parameters or tsunami height distribution, \(\eta_{i,j}^{k}\), above the ocean bottom pressure gauge network at a particular time, and d is the observed data or the left-hand side of Eq. (8) which includes \(h_{{{\text{f}}_{i,j} }}^{k + 1}\), one step after the particular time. A more detailed expression of Eq. (9) is

Using this method, the tsunami height distribution could be reproduced at any time as long as the tsunami stayed within the ocean bottom pressure gauge network. The method can be used for tsunami early warning by estimating the tsunami height field just after a great earthquake without earthquake source information. However, the resolution of the estimated tsunami height field would depend on the wavelength of the tsunami height distribution and the density of the ocean bottom pressure gauges. Numerical computation tests would be required to determine the resolution of this method.

3 Method for Numerical Computation Tests

A reference tsunami, used as the original tsunami for synthetic tests, was computed in the area off Tohoku as shown in Fig. 4. Tsunamis are numerically computed by solving the linear long-wave equations using the finite difference method with a staggered grid system (Satake 2015). The grid size of the tsunami computation was set at 1 arc-min (approximately 1.8 km). A simple rectangular fault model was chosen arbitrarily as shown in Fig. 4. In addition, the focal mechanism was chosen arbitrarily as a pure thrust type (strike = 270°, dip = 10°, rake = 90°). The length and width of the fault model were 250 and 150 km, respectively. The slip amount of 10 m was constant over the entire fault. Therefore, the moment magnitude was calculated to be M8.6. The source duration, the rise time, was chosen to be 80 s. The tsunami waveforms at the observation points were computed numerically from the reference fault model and transferred to the water-depth fluctuation, \(h_{\text{f}} \left( {x,y,t} \right)\), at the observation points using Eq. (3). The water-depth fluctuation was set to be observed at 40 s intervals, \(\Delta t\) in Eqs. (8, 9, or 10) because the time interval should be long enough to enable the water-depth fluctuation to be observed. In other words, the synthetic observed data, the water-depth fluctuation, at the observation points were created at 40 s intervals. These data were created until 120 s after the origin time of the earthquake in this study. In an actual instance, the duration of the earthquake would be unknown; therefore, we could continue obtaining the data as long as the strong shaking of the earthquake continued.

Ocean bottom pressure sensor distributions for three tests. a Sensors with 10 arc-min intervals (test 10 min), b sensors with 15 arc-min intervals (test 15 min), c sensors with 15 arc-min intervals in the north–south direction and sensors with 30 arc-min intervals in the east–west direction (test 15–30 min). The solid rectangle is the fault model used in this study

For the first numerical test, the ocean bottom pressure sensors were located using 10 arc-min intervals, approximately 20 km intervals, as shown in Fig. 4a (test 10 min). The tsunami height fields were computed by solving Eq. (10) at each 40 s interval using the synthetic observed data. Subsequently, the height fields were interpolated into 1 arc-min intervals to carry out the tsunami numerical simulation using the linear long-wave equations with the finite difference method. The tsunami numerical computation was initiated from the tsunami height field at 40 s after the earthquake. For each 40 s, when the tsunami height field from the synthetic observed data was available, the tsunami height field at that particular time was replaced in the tsunami numerical computation. The tsunami numerical computation was continued to finish 1 h of tsunami propagation.

Next, as a more realistic test, the ocean bottom pressure sensors were located using 15 arc-min intervals, approximately 30 km intervals (Fig. 4b, test 15 min). This was done because the ocean bottom pressure sensors in the S-NET (Fig. 1) connected by a cable at distance of 30 km apart. The procedure to compute a tsunami height field directly from the synthetic observed data at the sensors was the same as that for test 10 min. In addition, the tsunami numerical computation was the same as that for test 10 min.

Third, as the most realistic case, we used ocean bottom pressure sensors with 15 arc-min intervals along the north–south direction and sensors with 30 arc-min, approximately 60 km, intervals along the east–west direction (Fig. 4c, test 15–30 min). In the S-NET, the ocean bottom pressure sensors were located at a distance of approximately 50–60 km apart in a north–south direction and at a distance of approximately 30 km apart in an east–west direction (Fig. 1). Again, the procedure to compute the tsunami height field directly from the synthetic observed data was the same as that for test 10 min, as was the tsunami numerical computation.

4 Results of the Numerical Computation Tests

The tsunami height distributions at 40, 120, 200 and 600 s after the origin time of the earthquake for the reference tsunami are shown in Fig. 5a–d, respectively. These distributions for test 10 min are shown in Fig. 5e–h; those for test 15 min are shown in Fig. 5i–l; and those for test 15–30 min are shown in Fig. 5m–p. The tsunami waveforms at seven locations shown in Fig. 5 as open black circles are compared in Fig. 6 for the reference tsunami, the estimated tsunami of test 10 min, that of test 15 min, and that of test 15–30 min.

Comparisons of tsunami waveforms at seven locations, the open black circles in Fig. 5, for a the reference tsunami in red, the estimated tsunamis for b test 10 min, c test 15 min, and d test 15–30 min from Fig. 4 is in black. TG1 is located closest to the land, and TG7 is located farthest from the land

For test 10 min, the tsunami height distributions were almost the same as those for the reference tsunami. This indicated that the method to obtain the tsunami height distribution at a certain time from the observed pressure data at the sensors functioned well. A comparison of the waveforms (Fig. 6b) showed that the reference tsunami waveforms were reproduced well by those waveforms estimated from the synthetic observed pressure data at the sensors. However, the high frequency part of the reference tsunami was underestimated slightly in terms of the tsunami height.

For test 15 min, the tsunami height distributions (Fig. 5) were almost the same as those for the reference tsunami except the small scale perturbations. At 40 and 120 s after the origin time of the earthquake, the uplifted areas were leaked out slightly from those for the reference tsunami. A comparison of the waveforms (Fig. 6c) showed that, in general, the reference tsunami waveforms were reproduced well by those waveforms estimated from synthetic observed pressure data. However, the estimated tsunami waveforms include additional small higher frequency contents.

For test 15–30 min, the tsunami height distributions were almost the same as that of the reference tsunami. However, more small scale perturbations were generated compared with those from test 15 min. At 40 and 120 s after the origin time of the earthquake, the uplifted areas were leaked out more than were those for test 15 min. At 200 s after the origin time of the earthquake, the uplifted and subsided areas were also leaked out from those for the reference tsunami. A comparison of the waveforms (Fig. 6d) showed that, in general, the reference tsunami waveforms were reproduced well by those waveforms estimated from synthetic observed pressure data, but again, the estimated tsunami waveforms included additional small higher frequency contents. In addition, the maximum estimated tsunami heights were underestimated slightly from the reference tsunami.

5 Conclusion

We developed a new method to reproduce tsunami height distribution in and around the source area, at a certain time, from the pressure data observed at numerous ocean bottom pressure sensors without any information on the tsunami source. The method functioned well for the synthetic tsunami from a simple rectangular fault with an ocean bottom pressure sensor network with 10 and 15 arc-min intervals. For the ocean bottom pressure sensors with 15 arc-min intervals along the north–south direction and the sensors with 30 arc-min intervals along the east–west direction, the method functioned well enough to reproduce the tsunami height field generally. This indicated that the method could be used for tsunami early warning to estimate the tsunami height field just after a great earthquake without any earthquake source information.

References

Geist, E. L., Fritz, H. M., Rabinovich, A. B., & Tanioka, Y. (2016). Introduction to global tsunami science: past and future. Pure and Applied Geophysics. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55480-8_1.

Gusman, R. G., Sheehan, A. F., Satake, K., Heidazadeh, M., Mulia, I. E., & Maeda, T. (2016). Tsunami data assimilation of Cascadia seafloor pressure gauge records from the 2012 Haida Gwaii earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters. doi:10.1002/2016GL068368.

Gusman, A. R., Tanioka, Y., Sakai, S., & Tsushima, H. (2012). Source model of the great 2011 Tohoku earthquake estimated from tsunami waveforms and crustal deformation data. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 341, 234–242.

Kanazawa, T. (2013). Japan trench earthquake and tsunami monitoring network of cable-linked 150 ocan bottom observatories, and its impact to earth disaster science. Proceedings of the International Conference Underwater Technology. doi:10.1109/UT.2013.6519911.

Maeda, T., Obara, K., Shinohara, M., Kanazawa, T., & Uehira, K. (2015). Successive estimation of a tsunami wavefield without earthquake source data: a data assimilation approach toward real-time tsunami forecasting. Geophysical Research Letters, 42, 7923–7932. doi:10.1002/2015GL065588.

Melgar, D., & Bock, Y. (2013). Near-field tsunami models with rapid earthquake source inversions from land- and ocean-based observations: the potential for forecast and warning. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 118, 5939–5955. doi:10.1002/2013JB010506.

Mori, N., Takahashi, T., & The 2011 Tohoku Earthquake Tsunami Joint Survey Group. (2012). Nationwide post event survey and analysis of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake tsunami. Coastal Engineering Journal, 54(1), 1250001. doi:10.1142/S0578563412500015.

Ozaki, T. (2011). Outline of the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake (M w 9.0)—tsunami warnings/advisories and observations. Earth Planets Space, 63, 827–830. doi:10.5047/eps.2011.06.029.

Saito, T., Ito, Y., Inazu, D., & Hino, R. (2011). Tsunami source of the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake, Japan: inversion analysis based on dispersive tsunami simulations. Geophysical Research Letters, 38, L00G19. doi:10.1029/2011GL049089.

Satake, K. (2015). Tsunamis, in treatise on geophysics, vol 4 (2nd ed., pp. 477–504. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Satake, K., Fujii, Y., Harada, T., & Namegaya, Y. (2013). Time and space distribution of coseismic slip of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake as inferred from Tsunami waveform data. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 103(2B), 1473–1492.

Tanioka, Y., & Seno, T. (2001). The sediment effect on tsunami generation of the 1896 Sanriku tsunami earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters, 28, 3389–3392.

Tsushima, H., Hino, R., Fujimoto, H., Tanioka, Y., & Imamura, F. (2009). Near-field tsunami forecasting from cabled ocean bottom pressure data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 114, B06309. doi:10.1029/2008JB005988.

Tsushima, H., Hino, R., Ohta, Y., Iinuma, T., & Miura, S. (2014). tFISH/RAPiD: rapid improvement of near-field tsunami forecasting based on offshore tsunami data by incorporating onshore GNSS data. Geophysical Research Letters, 41, 3390–3397. doi:10.1002/2014GL059863.

Tsushima, H., Hino, R., Tanioka, Y., Imamura, F., & Fujimoto, H. (2012). Tsunami waveform inversion incorporating permanent seafloor deformation and its application to tsunami forecasting. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 117, B03311. doi:10.1029/2011JB008877.

Uehira, K., Kanazawa, T., Noguchi, S., Aoi, S., Kunugi, T., Matsumoto, T., Okada, Y., Sekiguchi, S., Shiomi, K., Shinohara, M., & Yamada, T. (2012). Ocean bottom seismic and tsunami network along the Japan Trench. In: Abstract OS41C-1736 presented at 2012 Fall Meeting, AGU.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Kenji Satake and Dr. Kenny Ryan for their valuable comments. This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, under its Earthquake and Volcano Hazards Observation and Research Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanioka, Y. Tsunami Simulation Method Assimilating Ocean Bottom Pressure Data Near a Tsunami Source Region. Pure Appl. Geophys. 175, 721–729 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-017-1697-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-017-1697-5