Abstract

Background

Recently, First Nations people were shown to be at high fracture risk compared with the general population. However, factors contributing to this risk have not been examined. This analysis focusses on geographic area of residence, income level, and diabetes mellitus as possible explanatory variables since they have been implicated in the fracture rates observed in other populations.

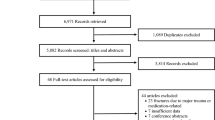

Methods

A retrospective, population-based matched cohort study of fracture rates was performed using the Manitoba administrative health data (1987-1999). The First Nations cohort included all Registered First Nations adults (20 years or older) as indicated in either federal and/or provincial files (n=32,692). Controls (up to three for each First Nations subject) were matched by year of birth, sex and geographic area of residence. After exclusion of unmatched subjects, analysis was based upon 31,557 First Nations subjects and 79,720 controls.

Results

Overall and site-specific fracture rates were significantly higher in the First Nations cohort. Income quintile, geographic area of residence, and diabetes were fracture determinants but the excess fracture risk of First Nations ethnicity persisted even after adjustment for these factors.

Conclusion

First Nations people are at high risk for fracture but the causal factors contributing to this are unclear. Further research is needed to evaluate the importance of other potential explanatory variables.

Résumé

Contexte

On a récemment démontré que le risque de fracture était plus élevé chez les membres des Premières nations que dans la population générale. Cependant, les facteurs pouvant contribuer à ce risque n’ont pas été examinés. La présente étude porte sur la région de résidence, le niveau de revenu et le diabète sucré, qui pourraient être des variables explicatives, car elles jouent un rôle dans les taux de fracture observés dans d’autres populations.

Méthode

À l’aide des données administratives sur la santé du Manitoba (1987-1999), nous avons mené une étude de cohortes représentative et rétrospective portant sur les taux de fracture. La cohorte des Premières nations comprenait tous les membres des Premières nations d’âge adulte (20 ans et plus) désignés comme étant „ inscrits ” dans les bases de données fédérales et/ou provinciales (n = 32 692). Les témoins (jusqu’à trois pour chaque sujet des Premières nations) ont été assortis aux cas selon l’année de naissance, le sexe et la région de résidence. Après avoir exclu les cas non assortis, notre analyse s’est fondée sur 31 557 sujets des Premières nations et 79 720 témoins.

Résultats

Les taux de fracture globaux et par site étaient sensiblement plus élevés dans la cohorte des Premières nations. Le quintile de revenu, la région de résidence et le diabète étaient des déterminants du taux de fracture, mais il subsiste un risque de fracture plus élevé chez les membres des Premières nations, même après ajustement selon ces trois facteurs.

Conclusion

Les membres des Premières nations présentent un risque de fracture élevé, mais les facteurs causals de cette situation ne sont pas clairs. Il faudrait pousser la recherche pour évaluer l’importance d’autres variables explicatives possibles.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: An observational study. Lancet 1999;353(9156):878–82.

Forsen L, Sogaard AJ, Meyer HE, Edna T, Kopjar B. Survival after hip fracture: Short- and long-term excess mortality according to age and gender. Osteoporos Int 1999;10(1):73–78.

Meyer HE, Tverdal A, Falch JA, Pedersen JI. Factors associated with mortality after hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 2000;11(3):228–32.

Wiktorowicz ME, Goeree R, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Papadimitropoulos E. Economic implications of hip fracture: Health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporos Int 2001;12(4):271–78.

Papadimitropoulos EA, Coyte PC, Josse RG, Greenwood CE. Current and projected rates of hip fracture in Canada. CMAJ 1997;157(10):1357–63.

van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 2001;29(6):517–22.

Grisso JA, Kelsey JL, Strom BL, O’Brien LA, Maislin G, LaPann K, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in black women. The Northeast Hip Fracture Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994;330(22):1555–59.

Calder SJ, Anderson GH, Harper WM, Gregg PJ. Ethnic variation in epidemiology and rehabilitation of hip fracture. BMJ 1994; 309(6962):1124–25.

Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, et al. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 1998;8(5):468–89.

MacMillan HL, MacMillan AB, Offord DR, Dingle JL. Aboriginal health. CMAJ 1996;155(11):1569–78.

Leslie WD, Derksen S, Metge C, Lix L, Salamon EA, Wood Steiman P, Roos LL. Fracture risk among First Nations people: A retrospective matched cohort study. CMAJ 2004;171(8):869–73.

Farahmand BY, Persson PG, Michaelsson K, Baron JA, Parker MG, Ljunghall S. Socioeconomic status, marital status and hip fracture risk: A population-based case-control study. Osteoporos Int 2000;11(9):803–8.

Varenna M, Binelli L, Zucchi F, Ghiringhelli D, Gallazzi M, Sinigaglia L. Prevalence of osteoporosis by educational level in a cohort of post-menopausal women. Osteoporos Int 1999;9(3):236–41.

Bacon WE, Hadden WC. Occurrence of hip fractures and socioeconomic position. J Aging Health 2000;12(2):193–203.

Kaastad TS, Meyer HE, Falch JA. Incidence of hip fracture in Oslo, Norway: Differences within the city. Bone 1998;22(2):175–78.

Sernbo I, Johnell O, Andersson T. Differences in the incidence of hip fracture. Comparison of an urban and a rural population in southern Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand 1988;59(4):382–85.

Johnell J, Oden A, Rosengren B, Mellstrom D, Kanis J. National variation in hip fracture rate in Sweden depends on latitude and season - A cohort study of 26 million observation years. Osteoporosis Int 2002;13(Suppl. 1):S8.

Schwartz AV, Sellmeyer DE, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Tabor HK, Schreiner PJ, et al. Older women with diabetes have an increased risk of fracture: A prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86(1):32–38.

Forsen L, Meyer HE, Midthjell K, Edna TH. Diabetes mellitus and the incidence of hip fracture: Results from the Nord-Trondelag Health Survey. Diabetologia 1999;42(8):920–25.

Martens PJ, Bond R, Jebamani LS, Burchill CA, Roos NP, Derksen SA, et al. The Health and Health Care Use of Registered First Nations People Living in Manitoba: A Population-Based Study. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, 2002.

Jebamani L, Burchill C, Martens P. Using data linkage to identify First Nations Manitobans: Technical, ethical and political issues. Can J Public Health 2005;96(Suppl. 1):S28–S32.

Roos NP, Shapiro E. Revisiting the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation and its population-based health information system. Med Care 1999;37(Suppl. 6):JS10–JS14.

Roos LL, Sharp SM, Wajda A. Assessing data quality: A computerized approach. Soc Sci Med 1989;28(2):175–82.

Roos LL, Walld RK, Romano PS, Roberecki S. Short-term mortality after repair of hip fracture. Do Manitoba elderly do worse? Med Care 1996;34(4):310–26.

Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY, Cauley JA, Ensrud K, Browner WS, et al. BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: Long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18(11):1947–54.

Income Quintiles Based on the 1996 Census. Winnipeg, MB. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, 2003. Available on-line at https://doi.org/www.umanitoba.ca/academic/centres/mchp/concept/diet/income/income_quintile.html (Accessed September 3, 2003)

Blanchard JF, Ludwig S, Wajda A, Dean H, Anderson K, Kendall O, Depew N. Incidence and prevalence of diabetes in Manitoba, 1986–1991. Diabetes Care 1996;19(8):807–11.

McCulloch CE, Searle SR. Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2001.

Fox J. Applied Regression Analysis, Linear Models, and Related Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997.

Spindler A, Lucero E, Berman A, Paz S, Vega E, Mautalen C. Bone mineral density in a native population of Argentina with low calcium intake. J Rheumatol 1995;22(11):2148–51.

Beyene Y, Martin MC. Menopausal experiences and bone density of Mayan women in Yucatan, Mexico. Am J Human Biol 2001;13(4):505–11.

Hamman RF, Bennett PH, Miller M. The effect of menopause on serum cholesterol in American (Pima) Indian women. Am J Epidemiol 1975;102(2):164–69.

Perry HM, III, Bernard M, Horowitz M, Miller DK, Fleming S, Baker MZ, et al. The effect of aging on bone mineral metabolism and bone mass in Native American women. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46(11):1418–22.

Chen Z, Maricic MJ, Going SB, Lohman TG, Altimari BR, Bassford TL. Comparative findings in bone mineral density among postmenopausal Native American women and postmenopausal White women residing in Arizona. Bone 2003;23(Suppl. 1):S592.

van Daele PL, Stolk RP, Burger H, Algra D, Grobbee DE, Hofman A, et al. Bone density in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Rotterdam Study. Ann Intern Med 1995;122(6):409–14.

Stolk RP, van Daele PL, Pols HA, Burger H, Hofman A, Birkenhager JC, et al. Hyperinsulinemia and bone mineral density in an elderly population: The Rotterdam Study. Bone 1996;18(6):545–49.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Acknowledgements of Sources of Support: Supported by a grant from the Health Sciences Centre Foundation. The authors are indebted to Health Information Services and Manitoba Health for providing the data used in this study, to the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch and Indian and Northern Affairs Canada for permission to use the Status Verification System, and to the Health Information Research Committee of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs for actively supporting this work. The results and conclusions are those of the authors, and no official endorsement by Manitoba Health is intended or should be inferred. Special thanks to Ms. Doreen Sanderson, Dr. John O’Neil and Dr. Patricia Martens for their assistance in this project.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leslie, W.D., Derksen, S.A., Metge, C. et al. Demographic Risk Factors for Fracture in First Nations People. Can J Public Health 96 (Suppl 1), S45–S50 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405316

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405316