Abstract

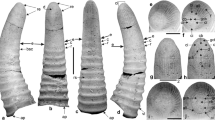

Life-cycle, post-embryonic development, as well as organization and development of gonads, have been investigated in 1,970 specimens of Rhabdomolgus ruber Keferstein (1863), dredged near Helgoland from September 1968 to November 1969. The post-embryonic development is divided into 8 stages differing in number of tentacles. Five secondary tentacles are added, in regular sequence, to the 5 primary tentacles. There is only one reproductive period per year, which lasts from April to May. It is estimated that the life span of individuals ranges over 2 or 3 years. Cultivation experiments corroborate the values for duration of the 4 youngest stages calculated from the results of dredgings. Stage 1 (5 tentacles) lasts more than 44 days, stage 2 (5 to 6 tentacles) 11 days, stage 3 (5 to 7 tentacles) 12 days, and stage 4 (5 to 8 tentacles) 30 days. R. ruber hibernates at stage 5 (8 tentacles). The development of the gonad is analysed in detail from the first anlage in the pentactula to the condition in adult individuals. Eggs develop in the front part of the female gonad; yolk is produced in the inner epithelial layer of the middle part. The eggs migrate through the ovarial connective tissue to the tip of the ovary. R. ruber lives in the uppermost 2 cm of the sediment (“Amphioxus-sand”) near Helgoland (southern North Sea). Moving its tentacles over its mouth, the animal feeds from detritus. R. ruber is confined to the mesopsammal biotope. Adhesive capacity of glandular tentacles, resistance to mechanical damage, and direct ontogeny must be regarded as characteristic adaptations to mesopsammal life. The simple organisation of the gonads and the presumably free discharge of germ cells into the ambient sea water represent phylogenetically primitive properties of the species.

Zusammenfassung

-

1.

Jugendentwicklung, Lebenszyklus, Bau und Entwicklung der Geschlechtsorgane werden an 1970 Individuen von Rhabdomolgus ruber Keferstein (1863) aus Dredschfängen (Helgoland) von September 1968 bis November 1969 untersucht.

-

2.

Die Jugendentwicklung läßt sich in 8 Stadien einteilen. Diese unterscheiden sich auf Grund der Tentakelzahl. Zu den 5 Primärtentakeln treten in gesetzmäßiger Folge 5 Sekundärtentakel.

-

3.

Der Lebenszyklus zeigt nur eine Reproduktionsphase pro Jahr, und zwar im Frühjahr. Die Lebensdauer wird mit 2 bis 3 Jahren angenommen.

-

4.

Hälterungsversuche bestätigen die für die Entwicklungsdauer der frühen Stadien aus dem natürlichen Lebensraum ermittelten Zeitspannen. Stadium 1 (5 Tentakel) umfaßt mehr als 44 Tage, Stadium 2 (5 bis 6 Tentakel) 11 Tage, Stadium 3 (5 bis 7 Tentakel) 12 Tage und Stadium 4 (5 bis 8 Tentakel) 30 Tage.

-

5.

Im Stadium 5 (8 Tentakel) erfolgt die Überwinterung.

-

6.

Die Entwicklung der Gonade wird von der ersten Anlage bei der Pentactula bis zum geschlechtsreifen Tier in allen Einzelheiten analysiert.

-

7.

Die Bildung der Eizellen erfolgt im vorderen Abschnitt der weiblichen Gonade, die Dotterproduktion im mittleren Teil im Innenepithel. Die Eier wandern im Bindegewebe der Gonade bis in den blind endenden Zipfel des Ovars.

-

8.

Rhabdomolgus ruber kriecht in den obersten 2 cm des Sediments (Helgoländer Amphoxusgrund) umher. Die Tiere streifen Detrituspartikel mit ihren Tentakeln an der Mundöffnung ab.

-

9.

In einer Lebensformanalyse wird Rhabdomolgus ruber dem Lebensraum Mesopsammal zugeordnet. Mit Haftvermögen durch drüsenreiche Tentakel, Schutz gegen mechanische Einflüsse und direkter Entwicklung zeigt die Art charakteristische Adaptationen. In der einfachen Organisation der Gonaden und der wahrscheinlich freien Ausschüttung der Geschlechtsprodukte manifestieren sich ursprüngliche Merkmale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literatur

Adam, H. und G. Czihak: Arbeitsmethoden der makroskopischen und mikroskopischen Anatomie, 583 pp. Stuttgart: Fischer Verl. 1964.

Ax, P.: Populationsdynamík, Lebenszyklen und Fortpflanzungsbiologie der Mikrofauna des Meeressandes. Verh. dt. zool. Ges. (Innsbruck 1968) 66–113 (1969).

Becher, S.: Über Synapta minuta n.sp., eine brutpffegende Synaptide der Nordsee und über die kontraktilen Rosetten der Holothurien. Zool. Anz. 30, 505–509 (1906).

— Rhabdomolgus ruber Keferstein und die Stammform der Holothurien. Z. wiss. Zool. 88, 545–689 (1907).

— Beiträge zur Morphologie und Systematik der Paractinopoden. Zool. Jb. [Anat. Ont. Tiere] 29, 315–361 (1910).

Cherbonnier, G.: Recherches sur les synaptes (holothuries, apoda) de Roscoff. Archs Zool. exp. gén. (Notes et revue) 90 (3), 163–185 (1953).

Clark, H. L.: Synapta vivipara: a contribution to the morphology of echinoderms. Mem. biol. Lab. Johns Hopkins Univ. 4 (2), 53–88 (1898).

Engel, H.: 6. Echinodermata. Fauna Ned. 59, 59–86 (1932).

Hagmeier, A. und J. Hinrichs: Bemerkungen über die Ökologie von Branchiostoma lanceolatum und das Sediment seines Wohnortes. Senckenbergiana Biol. 13, 255–267 (1931).

Hyman, L. H.: The invertebrates, 4. Echinoderms, 763 pp. New York: McGraw-Hill 1955.

Jones, N. S., J. M. Kain and A. H. Stride: The movement of sand waves on Warts Bank, Isle of Man. Mar. Geol. 3, 329–336 (1965).

Keferstein, W.: Unters, niedere Seetiere. Über Rhabdomolgus ruber g. et sp. n., eine neue Holothurie. Z. wiss. Zool. 12, 34–35 (1863).

Ludwig, H.: Echinodermen. a. Die Seewalzen. Bronn's Kl. Ordn. Tierreichs 2, 460 (1889–1892).

— Ein wiedergefundenes Tier: Rhabdomolgus ruber Kefebstein. Zool. Anz. 28, 458–459 (1905)

Mortensen, T.: Die Echinodermenlarven. Nord. Plankt. 9, 369 (1901).

— und I. Lieberkind: Echinoderma. Tierwelt N.- u. Ostsee 8, 1–127 (1928).

Nyholm, K.: Development and larval form of Labidoplax buski. Zool. Bijdr. 29, 239–254 (1954).

Rao, G. C.: On Psammothuria ganapatii n.g., n.sp., an interstitial holothurian from the beach sands of Waltair Coast and its autecology. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. 67 B, 201–206 (1968).

Remane, A.: Die Besiedlung des Sandbodens im Meere und die Bedeutung der Lebensformtypen für die Ökologie. Verh. dt. zool. Ges. (Wilhelmshaven 1951) 327–359 (1952).

Romeis, B.: Mikroskopische Technik, 15. Aufl. 695 pp. München: Oldenbourg 1948.

Runnström, S.: Entwicklung von Leptosynapta inhaerens. Bergens Mus. Årb. (Natur R.) 1, 1–80 (1928).

Selenka, E.: Beiträge zur Anatomie und Systematik der Holothurien. Z. wiss. Zool. 17, 291–374 (1867).

— Zur Entwicklung der Holothurien. Z. wiss. Zool. 27, 155–178 (1876).

Semon, R.: Beiträge zur Naturgeschichte der Synaptiden des Mittelmeeres 1. Mitt. zool. Stn Neapel 7, 272–300 (1887).

Swedmark, B.: The interstitial fauna of marine sand. Biol. Rev. 39, 1–42 (1964).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Communicated by O. Kinne, Hamburg

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Menker, D. Lebenszyklus, Jugendentwicklung und Geschlechtsorgane von Rhabdomolgus ruber (Holothuroidea: Apoda). Marine Biology 6, 167–186 (1970). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00347247

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00347247