Abstract

Purpose of Review

Researchers from five social science disciplines—anthropology, criminology, economics, geography, and political science—review the literature on climate change and conflict, focusing on the contributions since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s Fifth Assessment Report.

Recent Findings

These authors find little evidence for direct pathways from climate change to violence, especially for group-level violence and armed conflict. However, there is stronger evidence for indirect effects in agricultural and other vulnerable settings and for exacerbating ongoing violence rather than initiating new violence. The authors also emphasize the importance of governance and institutions, adaptive capacity, and potential cooperative behavior in moderating violence.

Summary

Looking across disciplines and employing the full range of research synthesis tools can improve the characterization and communication of the evidence. Focusing on interactions of climate mitigation and adaptation policies with conflict as well as opportunities for peace building can provide more actionable research for the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) are unequivocally causing increases in the Earth’s global mean temperature, leading to a wide range of climate impacts. In the absence of stringent climate policy—e.g., holding the global mean temperature rise to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels with an eye to limiting the increase to 1.5 °C—the physical impacts of climate change are projected to be widespread with the potential to affect almost every aspect of human well-being [1]. The scope of these impacts has prompted serious concern that climate change may increase or alter the propensity for human violence and conflict. In this special issue for Current Climate Change Reports entitled “Disciplinary Perspectives on the Relationship Between Climate Change and Human Conflict,” we invited scholars from five social science disciplines—anthropology, criminology, economics, geography, and political science—to summarize the state of the literature on climate change and the violent outcomes (e.g., civil war, social unrest, interpersonal violence, criminal activity) that are salient to their field. We developed this issue with three goals in mind:

-

1.

To provide an updated summary of the literature on climate change and human conflict, focusing on the work since the synthesis in the International Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5),

-

2.

To highlight the disciplinary contributions and present opportunities to improve the synthesis across disciplines, and

-

3.

To present some initial guidance on the research directions for the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6).

In this paper, I provide a brief background and motivation for this special issue and present summaries of the manuscripts. I also discuss the opportunities and challenges for synthesizing this broader base of evidence on the relationships between climate change and conflict as well as future directions for the climate–conflict research community in the lead-up to AR6.

Background and Motivation

In the past decade, climate change and its impacts on human violence and conflict have received increased attention from the academic community. In influential statements from the security community, climate change was conceptualized as a “threat multiplier” that would increase the risks of conflict by exacerbating known pathways, namely, economic conditions, food production, access to clean water, and human displacement [2]. While the security community subsequently updated its description to present climate change as a catalyst to conflict [3], the research from the academic community that coincided with AR5 did not generate the same degree of consensus on the role of climate change on conflict. This debate may be best exemplified by a series of papers that presented contradictory conclusions of the relationship between climate and conflict. Employing a research synthesis approach that combines empirical evidence known as meta-analysis, Hsiang et al. (2013, 2014a, 2014b) found a consistent and robust relationship between climatic variables and a range of forms of human conflict and violence [4,5,6]. Reviewing these results, Buhaug et al. (2014a, 2014b) concluded that the relationships are weak and inconsistent [7, 8].

The output from the academic community as well as the state of the debate has also been captured by the IPCC. Starting with the Second Assessment Report (SAR) of the state of the knowledge on climate change, the IPCC has considered the impact of climate on conflict. However, until the AR5, there was little systematic evidence in the peer-reviewed literature [9]. Reflecting the increase in the available literature, the effect of climate change on human security and armed conflict were more prominent, especially in the AR5’s Human Security chapter [10]. The report concludes that there is “justifiable common concern that climate change or changes in climate variability increase the risk of armed conflict in certain circumstances, even if the strength of the effect is uncertain.” In addition to the synthesis statements, the IPCC’s key findings are qualified by the author teams’ confidence (a qualitative synthesis of evidence and agreement) in that finding and, when the evidence is sufficient, a probabilistic characterization of likelihood or degree of uncertainty in that outcome [11]. When possible, the degree of uncertainty is to be expressed probabilistically drawing on either statistical analysis or expert judgment. In AR5, the author team attributed “medium evidence” that climate change may increase the risk of armed conflict, based on the “robust knowledge of the factors that increase the risk of civil wars and medium evidence that some of these factors are sensitive to climate change.” Here, the authors are highlighting the potential for indirect pathways where climate change leads to conflict by influencing its robust correlates, namely, economic performance and state capacity. However, the authors concluded that “confident statements about the effects of future changes in climate on armed conflict are not possible given the absence of generally supported theories and evidence about causality” [12]. However, this careful statement based on the available literature was weakened by statements to the contrary in other chapters [13]. Author teams for emergent risks and key vulnerabilities (Chapter 19) and the regional chapter on Africa (Chapter 22) concluded that there was greater support for climate–conflict relationships. By contrast, Chapter 18 on detection and attribution dismissed the relationships.

Following on AR5 and the interest that was generated by the academic community, research on climate change and conflict relationships has grown substantially with increased activity across a range of social science disciplines. Importantly, this presents an opportunity to move beyond the limitations of the quantitative analyses that defined the earlier debate and enhance the body of evidence on whether and how climate change may alter conflict [13, 14]. At the same time, this presents new challenges for the interpretation and synthesis. Structured synthesis techniques—namely, systematic review, meta-analysis, weight of evidence, and expert elicitation—that are more widely employed in the medical [15] and regulatory fields [16] may be useful compliments to the IPCC narrative approach [17]. Additionally, given the importance of these relationships for policy, there is a pressing need to improve and expand the body of evidence. By focusing on the literature that has been generated since AR5, these reviews also provide timely updates to the agreements and controversies across the climate–conflict research community. Finally, the chapter outlines for AR6 have been adopted in September 2017 [18], presenting an opportunity to reflect on the state of the literature, the next steps, and the possible links to the AR6 outline.

Selection of Disciplines and Authors

Developing the list of disciplines started with the review of the existing peer-reviewed literature as well as contributions at major disciplinary conferences. While efforts from economics and political science have largely dominated the debates on climate change and conflict, a growing body of meaningful contributions from other disciplines, such as anthropology, geography, and criminology, is providing more insight into these complex relationships. There are overlaps in the contributions as the perspectives, methods, and departments are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Further, some disciplines employ the work from others as more of a starting point for their own investigations and, at times, find only a subset of the evidence compelling. However, there are often different ways of interpreting the same information. This can generate opportunities to highlight consistencies as well as controversies.

After establishing the disciplines, an initial author list was developed by searching for peer-reviewed publications on climate change and endpoints of civil war, social unrest, and violence combined with disciplines. For some disciplines, significantly more scholarly output was identified than others. Authors were first identified based on publication counts and citations. If these authors were not available, nominations for colleagues were solicited from the initial list. The list of disciplines and contributors that are part of this special issue is presented in Table 1.

Sociology was on the initial list of disciplines to be included in this special issue. In a National Science Foundation-funded workshop on sociological perspectives on global climate change, Nagel et al. (2008) identified that there were opportunities for sociological research to provide insights into “questions of conflict and security, and the impacts on civil society of militarized responses to climate change” [19]. Several prominent sociologists, as well as the Environment and Technology and the Peace, War, and Social Conflict sections of the American Sociological Association (ASA), were approached. However, all authors declined indicating that this was not their area of expertise. A small number—often more junior faculty—expressed interest in addressing the intersection of climate change and conflict, while at the same time, noting that there was not much of a body of literature from their discipline. Looking at recent literature—importantly Bonds [20]—there appear to be more interest and the potential for a literature synthesis in the near term. Additionally, a manuscript reviewing the contributions from psychology was expected to be part of the special issue; this manuscript may be published separately from this issue.

Overview of the Papers

Looking across the disciplines provides an opportunity to expand the conceptual models, mechanisms, and the types of evidence that can be brought to bear when making statements regarding the degree of and reasons for agreement and disagreement and the uncertainty in the relationships between climate and conflict. In each piece, the authors were asked to provide a brief introduction to how their discipline approaches the relationship between climate and violence, summarize the literature with an emphasis on publications after AR5—highlighting the areas of agreement and controversy—and make recommendations on the next steps for their research community. Before discussing approaches to synthesize the literature, I present a brief summary of each paper along the following dimensions: (1) types of violence or conflict and the proposed mechanisms, (2) disciplinary approaches, and (3) conclusions about the state of the literature.

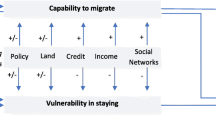

Political Science

Theisen (2017) takes on the challenge of synthesizing the work from political science focusing on collective violence, namely, armed conflict [21]. Political science draws on a particularly rich set of theories on opportunity costs and grievance, especially in the presence of politically relevant identities that have their roots in the literature on environmental factors and violence [e.g. 22]. Changes in food production and migration due to climatic factors are commonly cited mechanisms; however, it is generally acknowledged that neither will unconditionally lead to violence with institutions and state capacity playing a critical role in moderating the likelihood of conflict. Much of the work in this area mines the contemporaneous records of weather anomalies and violence to conduct empirical analyses; however, qualitative cases studies and mixed-method approaches are also being applied. In the literature since AR5, Theisen (2017) concludes that there is some evidence of a link between weather anomalies and collective violence, with the strongest indication for studies that explicitly model the effects of shocks indirectly via, e.g., food production or migration to conflict, and more so for ongoing violence than for initiating new collective violence [e.g., 23, 24]; however, he notes that part of the literature cautions against a dramatizing and simplistic focus on collective violence in the global South as this may be counterproductive in informing policy choices.

Economics

Koubi (2017) investigates the theoretical arguments and empirical evidence that connect climate change to conflict through the effects of climate change on economic factors [25]. As low per capita incomes and economic contraction are robust correlates to conflict [26, 27] and there is some evidence that economic growth is sensitive to climate change and variability [28], AR5 accorded medium evidence and medium agreement to the climate–economic–conflict pathway. Looking primarily at empirical analyses, Koubi (2017) reviewed macro (e.g., GDP) and micro (e.g., prices) indicators of economic underperformance and the link to a range of violent outcomes from armed conflict to lower-level forms of group violence. Koubi (2017) concludes that there is no robust evidence for a pathway from climate change to armed conflict through overall depressed economic activity. However, disaggregated analyses that focus on agricultural productivity and food prices reveal a more consistent relationship with social unrest such as demonstrations and riots.

Geography

Abrahams and Carr (2017) consider much of the same conflict literature—focusing on collective violence and armed conflict—as Theisen (2017) and Koubi (2017), but from the perspective of geography and political ecology [29]. They present the range of tools that geographers employ for conflict studies, including mapping, remote sensing, qualitative case studies, critical studies, and discourse analysis as complements to the large-N statistical analysis. They emphasize the importance of place- and context-specific research in understanding the potential influence of climate on conflict by capturing the more complex relationships between changes in climate, vulnerability, adaptation, and conflict [e.g. 30]. They conclude that the literature does not support a unilinear causal relationship between climate and conflict but more strongly supports a complex, place-specific relationship between the two which can result in climate change impacts exacerbating or ameliorating other drivers of conflict. This suggests that larger-scale studies which aggregate climate/conflict outcomes may fail to capture salient factors that produce these outcomes in particular places. Finally, they highlight how geographic and political ecological approaches can help identify how adaptation policies and projects that aim to reduce vulnerability may be used as part of environmental peace building or carry the risk of inadvertently producing unrest and violence [31].

Anthropology

Schaffer (2017), an environmental anthropologist, begins by expanding the dimensions of conflict from armed conflict and group violence to include interpersonal (e.g., one-on-one aggression) and structural violence (e.g., violence from institutional structures, policies, and ideologies that value some segments of the population more than others) as well as cooperative behavior [32]. Anthropologists draw on both archeological (e.g., fossil records and excavations of settlements) and ethnographic (e.g., oral histories and interviews) evidence to investigate historical and current contexts [33]. Reviewing a number of historical and modern case studies, Schaffer (2017) comes to a similar conclusion as Abrahams and Carr (2017)—through complex interactions with social and environmental conditions, climate change can promote violence; however, climate change does not lead inevitably to conflict. Governance, institutional structures, and individuals’ social positions and identities will shape human agency and violence in the face of a changing climate.

Criminology

White (2017) examines the relationship between climate change, human behavior, social strain, and a diversity of criminal activities [34]. Criminology draws on the foundational disciplines of sociology and law and incorporates disciplinary expertise from other social sciences. White (2017) starts with the literature from psychology that highlights the links between temperature and violence that can lead to crime (e.g., mob violence and street riots); however, he expands on the place-based and situational aspects of crime [35]. For example, altered weather patterns may also alter opportunities for crime, although the impact, either positive or negative, will depend on the interactions with a location’s built and social infrastructures. Additionally, other impacts of climate change, such as migration, may introduce opportunities for people smuggling. Criminology also introduces another framing for understanding these relationships, namely, that the activities that contribute to global warming can be recast as “ecocide.” To the extent that governments and corporations take contrarian views on the effect of GHG emissions on climate change to preserve their interests while others suffer harm, criminology may also be highly relevant to promoting mitigation efforts.

Expanding the Disciplinary Lens: Next Steps and Challenges for Synthesis

Taken as a whole, the manuscripts in this issue can form the beginnings of a broader conversation on the relationships between climate change and different forms of violence. Drawing upon these manuscripts and recommendations of the authors as well as the literature from the IPCC and the broader research synthesis community, I present opportunities for the climate–conflict research community to improve the synthesis of the research as well as research directions for AR6: (1) employ the full range of research synthesis tools to characterize the evidence, (2) improve the characterization and delineation of the types of violence and pathways, (3) Focus on environmental peace building as well as the interactions of climate mitigation and adaptation policies with conflict, and (4) improve the communication of the models and methods that are used by social scientists to investigate climate and conflict relationships.

Employ the Full Range of Research Synthesis Tools to Characterize the Evidence

While the IPCC has increasingly sophisticated guidance for its author teams [11], structured research synthesis techniques—such as systematic review, meta-analysis, weight of evidence, and expert elicitation—can enhance this synthesis by improving transparency and providing additional insight into the areas of agreement and disagreement on the climate and conflict relationships. Overall, these papers concur that where the impacts of climate change can influence conflict, they are heavily moderated by interactions with contextual factors, such as grievances (e.g., ethnic conflict), weak institutions, and low adaptive capacity. The manuscripts in the special issue, however, also reveal many of the methodological challenges that motivated this issue. Taken as a whole, the large-N studies have not identified a relationship between climate, especially short-term variability in weather patterns, and large-scale conflict. Disaggregation of the violent events and restricting the analyses to vulnerable contexts have yielded support for a link in agricultural settings. At the same time, qualitative contributions continue to emphasize the importance of context that may be obscured in the quantitative analyses. Recognizing that some disagreements and uncertainty will persist, the structure and transparency of the synthesis can be improved by employing the full range of research synthesis tools to characterize the evidence in a systematic way. By coupling these techniques, more diverse information can be incorporated into the synthesis, balancing the rigor of the quantitative meta-analytic approaches with more inclusive approaches (e.g., systematic reviews and weight of evidence) [36, 37]. This may be especially valuable for incorporating the qualitative case studies that may improve the identification of the conditions where a change in an environmental attribute poses a risk with respect to conflict. Additionally, expert elicitation—which involves structured protocols to elicit information regarding unknown parameters and models and has been used by the physical climate science community [38]—may be employed to improve the understanding of the strength of the evidence, causality, and uncertainty in these estimates [39]. Expert elicitation could also enhance the extrapolation (e.g., out of sample) to future climate change and socioeconomic conditions.

Continue to Improve the Delineation and Characterization of the Forms of Violence and Pathways

It has been proposed that one reason for the disagreement is differing terminology and models make integration more difficult [13]. This need to better define and disaggregate the conflict and violent outcomes and pathways is reflected across the manuscripts. Both Koubi (2017) and Theisen (2017) find that while the overall effects for climatic variables on conflict are not robust, there are clearer links for agricultural income and food prices to conflict and social unrest. Similar care should be taken to define the climatic variable or conditions as well as shift the investigations from short-run (annual) anomalies to medium-run changes in average conditions [e.g., 40]. Clearer definitions and disaggregation may also enhance communication across disciplines as well as facilitate the use of structured review techniques, like systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis. Improving the understanding of the links between different forms of violence would also improve the inclusion criteria for a given synthesis. Synthesizing across the literature may also allow for better identification of the different pathways. For example, the recent research focusing on specific contexts, such as the case studies that are discussed by Abrahams and Carr (2017), can help refine the variables and mechanisms for the large-N quantitative effects in political science and economics. Additionally, while it is often noted that there are challenges drawing analogies from the archeological record for present day armed conflict, Shaffer (2017) uses these studies to broaden the examples of social stability, conflict, and cooperation over a wider range of climatic conditions than those observed in the contemporaneous record. Finally, several authors also suggest investigating whether and how climate change may lead to alternative forms of violence that are under-researched, including low-level conflict and non-physical violence (e.g., neglect and psychological violence).

Enhance the Literature and Consideration of Environmental Peacebuilding

There is also a growing recognition of the potential for environmental problems to present opportunities for cooperation as well as be used as a catalyst for peace building in regions with persistent conflict. In AR5, the link from conflict to enhanced vulnerability to climate change was characterized as having medium evidence and high agreement [2]. Regardless of uncertainty in the state of literature on the climate and conflict relationship, conflict poses numerous risks to countries and regions that are already vulnerable to the effects of climate change [41]. Peace-building activities stand out as a means of improving climate resilience. Viewing environmental issues through the lens of peace building may open additional avenues for these activities (e.g., [42]). Thus, paying more attention to these links, especially under the types of conditions that may occur more frequently under climate change, would represent an important contribution to the literature. This may be especially relevant as issues around transboundary as well as international and intra-national concerns related to shared water resources have been included in the high-level outline for AR6.

Improve the State of Knowledge on the Relationships Between Climate Policies and Conflict

In AR6, there is focus on the changing policy context of the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the high-level bullets for Working Group II focus on mitigation, adaptation, and trade-offs. Many of these trade-offs are relevant for conflict, although they are only explicitly mentioned with respect to competition and conflict with indigenous rights to land and water bodies. In fact, calls to investigate conflict within the context of climate policy are not new [9]; however, the upcoming special report on global warming to 1.5 °C and AR6 increases the saliency of this line of inquiry. In addition, it may be more actionable to investigate climate policies and their implementation. For example, guidance from human geography may be especially relevant for program design and monitoring to prevent violence. Other social sciences may be able to provide insight into other unintended consequences of these policies to well-being, health, and security. Finally, many of the authors raise the role of institutions and governance in human conflict. Looking at the influence of institutions through the lens of climate mitigation and adaptation policy opens new opportunities to investigate how governance influences conflict as well as the influence of these policies on broader issues of governance (e.g., [43]).

Leveraging Social Science to Enhance the Dialogue on Climate and Security

A common goal across the authors in this special issue is to spur action on mitigation by improving the literature on the risks. At the same time, there is a concern regarding the public discourse on “climatic reductionism”—a deterministic, neo-Malthusian model of how climatic change is linked to human violence and conflict as well as the potential risks associated with the securitization of climate change [44]. A more systematic consideration of the literature could enhance the policy discussion [45] as well as the representations in the popular media [46]. Additionally, as there is no common section to discuss the relationship between climate and conflict in AR6, there is an additional imperative to ensuring consistency in treatment across the chapters to avoid some of the issues encountered in AR5.Footnote 1 Here, the climate–conflict research community can provide especially valuable input by drawing on the social science efforts to improve the integration between the social and physical science disciplines [49] as well as the communication of climate policy [50] and general climate literacy [51].

Notes

Migration is included as a high-level bullet in Chapter 7 “Health, wellbeing and the changing structure of communities.” Migration has been proposed as a pathway from climate change to conflict. While a review of this literature is beyond the scope of this special issue, a cursory review reveals a similar pattern of contestation to the climate–conflict link that motivated this special issue. This is especially pronounced with the literature on the role of the drought in Syria in influencing the ongoing conflict through rural to urban migration [47, 48]. Research synthesis approaches may also be beneficial for identifying and summarizing the evidence for this pathway.

References

IPCC, 2014: Climate change 2014: synthesis report contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [core writing team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp.

CNA Military Advisory Board. National security and the accelerating risks of climate change. Arlington: CNA Corporation; 2014.

CNA Military Advisory Board. National security and the threat of climate change. Alexandria: CNA Corporation; 2007.

Hsiang SM, Burke M, Miguel E. Quantifying the influence of climate on human conflict. Science. 2013;341(6151):1235367.

Hsiang SM, Burke M, Miguel E. Reconciling climate-conflict meta-analyses: reply to Buhaug et al. Clim Chang. 2014;127(3–4):399–405.

Hsiang SM, Meng KC. Reconciling disagreement over climate-conflict results in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(6):2100–3.

Buhaug H, Nordkvelle J, Bernauer T, Böhmelt T, Brzoska M, Busby JW, et al. One effect to rule them all? A comment on climate and conflict. Clim Chang. 2014;127(3–4):391–7.

Buhaug H. Concealing agreements over climate—conflict results. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(6):E636.

Nordås R, Gleditsch NP. Climate change and conflict. Polit Geogr. 2007;26(6):627–38.

Adger WN, Pulhin JM, Barnett J, Dabelko GD, Hovelsrud GK, Levy M, et al. Human security. In: Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR, White LL, editors. Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 755–91.

Mastrandrea MD, Field CB, Stocker TF, Edenhofer O, Ebi KL, Frame DJ, et al. Guidance note for lead authors of the IPCC fifth assessment report on consistent treatment of uncertainties. Geneva: IPCC; 2010.

Gleditsch NP, Nordås R. Conflicting messages? The IPCC on conflict and human security. Polit Geogr. 2014;43:82–90.

Ide T, Scheffran J. On climate, conflict and cumulation: suggestions for integrative cumulation of knowledge in the research on climate change and violent conflict. Glob Chang Peace Secur. 2014;26(3):263–79.

Ide T. Research methods for exploring the links between climate change and conflict. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 2017;8(3):e456.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [Internet]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011 20 [Cited 2013 Dec 2]. Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org.

Robinson LA, Hammitt JK. Research synthesis and the value per statistical life. Risk Anal. 2015;35(6):1086–100.

Bergeijk P, Lazzaroni S. Macroeconomics of natural disasters: strengths and weaknesses of meta-analysis versus review of literature. Risk Anal. 2015;35(6):1050–72.

IPCC. Decision: chapter outline of the Working Group II contribution to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). IPCC; 2017.

Nagel J, Dietz T, and Broadbent J. Sociological perspectives on global climate change; Workshop report from workshop held May. 2008. Available at: http://www.asanet.org/sites/default/files/savvy/research/NSFClimateChangeWorkshop_120109.pdf.

Bonds E. Upending climate violence research: fossil fuel corporations and the structural violence of climate change. Hum Ecol Rev. 2016;22(2):3.

Theisen OM. Climate change and violence: insights from political science. Current Climate Change Reports 2017; In this issue.

Goldstone JA. Revolution and rebellion in the early modern world: population change and state breakdown in England, France, Turkey, and China. Abingdon: Routledge; 2016. p. 1600–850.

von Uexkull N, Croicu M, Fjelde H, Buhaug H. Civil conflict sensitivity to growing-season drought. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(44):12391–6.

Raleigh C, Choi HJ, Kniveton D. The devil is in the details: an investigation of the relationships between conflict, food price and climate across Africa. Glob Environ Chang. 2015;32:187–99.

Koubi V Climate change, the economy, and conflict. Current Climate Change Reports 2017; In this issue.

Ward MD, Greenhill BD, Bakke KM. The perils of policy by p–value: predicting civil conflicts. J Peace Res. 2010;47(4):363–75.

Hegre H, Sambanis N. Sensitivity analysis of empirical results on civil war onset. J Confl Resolut. 2006;50(4):508–35.

Dell M, Jones BF, Olken BA. What do we learn from the weather? The new climate–economy literature. J Econ Lit. 2014;52(3):740–98.

Abrahams D, Carr E. Understanding the connections between climate change and conflict: contributions from geography and political ecology. Current Climate Change Reports 2017; In this issue.

Vivekananda J, Schilling J, Smith D. Climate resilience in fragile and conflict-affected societies: concepts and approaches. Dev Pract. 2014;24(4):487–501.

Dabelko GD, Herzer L, Null S, Parker M, Sticklor R. Backdraft: the conflict potential of climate change adaptation and mitigation. Washington DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Environmental Change and Security Program Report 2013;14(2):1–60.

Schaffer LJ. An anthropological perspective on the climate change and violence relationship. Current Climate Change Reports 2017; In this issue.

Fiske SJ, Crate SA, Crumley CL, Galvin K, Lazrus H, Lucero L, et al. Changing the atmosphere: anthropology and climate change. Final report of the AAA Global Climate Change Task Force 2014;137.

White R. Criminological perspectives on climate change and violence. Current Climate Change Reports 2017; In this issue.

Brisman A, South N, White R. Environmental crime and social conflict: contemporary and emerging issues. Abingdon: Routledge; 2016.

Fann N, Gilmore EA, Walker K. Characterizing the long-term PM2.5 concentration-response function: comparing the strengths and weaknesses of research synthesis approaches. Risk Anal. 2016;36(9):1693–707.

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):59.

Zickfeld K, Morgan MG, Frame DJ, Keith DW. Expert judgments about transient climate response to alternative future trajectories of radiative forcing. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(28):12451–6.

Morgan MG. Use (and abuse) of expert elicitation in support of decision making for public policy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(20):7176–84.

de Juan A. Long-term environmental change and geographical patterns of violence in Darfur, 2003–2005. Polit Geogr. 2015;45:22–33.

Buhaug H. Climate change and conflict: taking stock. Peace Econ Peace Sci Public Policy. 2016;22(4):331–8.

Krampe F. Empowering peace: service provision and state legitimacy in Nepal’s peace-building process. Confl Secur Dev. 2016;16(1):53–73.

Gartzke E. Could climate change precipitate peace? J Peace Res. 2012;49(1):177–92.

Hartmann B. Converging on disaster. Geopolitics. 2014;19(4):757–83.

Oels A. From securitization of climate change to climatization of the security Fielkd. In: Scheffran J, editors. Climate change, human security and violent conflict. Berlin: Springer; 2012.

Schäfer MS, Scheffran J, Penniket L. Securitization of media reporting on climate change? A cross-national analysis in nine countries. Secur Dialogue. 2016;47(1):76–96.

Kelley CP, Mohtadi S, Cane MA, Seager R, Kushnir Y. Climate change in the fertile crescent and implications of the recent syrian drought. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(11):3241–6.

Selby J, Dahi OS, Fröhlich C, Hulme M. Climate change and the syrian civil war revisited. Polit Geogr. 2017;60:232–44.

Lewis KH, Lenton TM. Knowledge problems in climate change and security research. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang. 2015;6(4):383–99.

Victor DG. Embed the social sciences in climate policy. Nature. 2015;520(April):27–9.

Shwom R, Isenhour C, Jordan RC, McCright AM, Robinson JM. Integrating the social sciences to enhance climate literacy. Front Ecol Environ. 2017;15(7):377–384. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1519.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge Dr. Brian Soden and Dr. Robert Kopp for the invitation for this special issue and the editorial assistance of Lauren Greaves. She is also deeply indebted to Elizabeth Tennant for her diligent assistance in the research and review of the manuscripts.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by or in part by the US Army Research Laboratory and the US Army Research Office via the Minerva Initiative under grant number W911NF-13-1-0307.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Climate Change and Conflicts

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gilmore, E.A. Introduction to Special Issue: Disciplinary Perspectives on Climate Change and Conflict. Curr Clim Change Rep 3, 193–199 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-017-0081-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-017-0081-y