Abstract

Introduction

Previous studies of antihypertensive treatment of older patients have focused on blood pressure control, cardiovascular risk or adherence, whereas data on inappropriate antihypertensive prescriptions to older patients are scarce.

Objectives

The aim of the study was to assess inappropriate antihypertensive prescriptions to older patients.

Methods

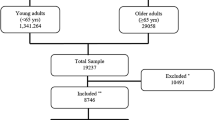

An observational, prospective multicentric study was conducted to assess potentially inappropriate prescription of antihypertensive drugs, in patients aged 75 years and older with arterial hypertension (HTN), in the month prior to hospital admission, using four instruments: Beers, Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions (STOPP), Screening Tool to Alert Doctors to the Right Treatment (START) and Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders 3 (ACOVE-3). Primary care and hospital electronic records were reviewed for HTN diagnoses, antihypertensive treatment and blood pressure readings.

Results

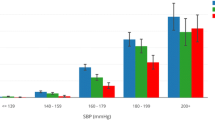

Of 672 patients, 532 (median age 85 years, 56% female) had HTN. 21.6% received antihypertensive monotherapy, 4.7% received no hypertensive treatment, and the remainder received a combination of antihypertensive therapies. The most frequently prescribed antihypertensive drugs were diuretics (53.5%), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) (41%), calcium antagonists (32.2%), angiotensin receptor blockers (29.7%) and beta-blockers (29.7%). Potentially inappropriate prescription was observed in 51.3% of patients (27.8% overprescription and 35% underprescription). The most frequent inappropriately prescribed drugs were calcium antagonists (overprescribed), ACEIs and beta-blockers (underprescribed). ACEI and beta-blocker underprescriptions were independently associated with heart failure admissions [beta-blockers odds ratio (OR) 0.53, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.39–0.71, p < 0.001; ACEIs OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.36–0.70, p < 0.001].

Conclusion

Potentially inappropriate prescription was detected in more than half of patients receiving antihypertensive treatment. Underprescription was more frequent than overprescription. ACEIs and beta-blockers were frequently underprescribed and were associated with heart failure admissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, et al. Hipertensión. Hipertens riesgo vasc. 2013;30:1–94. http://www.seh-lelha.org/pdf/Guia2013.pdf.

Gómez-Huelgas R, Martínez-Sellés M, Formiga F, Alemán Sánchez JJ, Camafort M, Galve E, et al. Management of vascular risk factors in patients older than 80. Med clínica. Elsevier; 2014 [cited 2015 Dec 17];143:134.e1–11. http://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-medicina-clinica-2-articulo-tratamiento-los-factores-riesgo-vascular-90334864.

Kaiser EA, Lotze U, Schäfer HH. Increasing complexity: which drug class to choose for treatment of hypertension in the elderly? Clin Interv Aging. 2014 [cited 2016 Jan 10];9:459–75. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3969251&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008 [cited 2016 Jan 10];358:1887–98. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18378519.

Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011 [cited 2016 Jan 6];5:259–352. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21771565.

Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren M, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by re. Eur Heart J. 2012 [cited 2014 Jul 10];33:1635–701. http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/33/13/1635.

Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015 [cited 2015 Nov 10];373:2103–16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26551272.

Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, Matsuoka H, Shimamoto K, Shimada K, et al. Target blood pressure for treatment of isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: valsartan in elderly isolated systolic hypertension study. Hypertension. 2010 [cited 2015 Dec 17];56:196–202. http://hyper.ahajournals.org/content/56/2/196.short.

O’rourke MF, Namasivayam M, Adji A. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. Minerva Med. 2009 [cited 2016 Jan 10];100:25–38. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19277002.

De Villar JHP, Miranda MG, Perez-Monteoliva NR, Gregori JA, Musso CG, Núñez JM. La hipertensión arterial en los pacientes octogenarios. Reflexiones sobre los objetivos, el tratamiento y sus consecuencias. Nefro Plus. 2011;4:18–28. http://www.revistanefrologia.com/es-publicacion-nefroplus-imprimir-articulo-la-hipertension-arterial-los-pacientes-octogenarios-reflexiones-sobre-los-objetivos-X1888970011001133.

Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. American Medical Association; 2003 [cited 2015 Aug 21];163:2716–24. http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=757456.

Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O’Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008 [cited 2016 Jan 10];46:72–83. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18218287.

Barry PJ, Gallagher P, Ryan C, O’mahony D. START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the Right Treatment)–an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 2007 [cited 2016 Jan 10];36:632–8. http://ageing.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/long/36/6/632.

Welsh TJ, Gladman JR, Gordon AL. The treatment of hypertension in people with dementia: a systematic review of observational studies. BMC Geriatr. 2014 [cited 2016 Jan 10];14:19. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3923425&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

San-José A, Agustí A, Vidal X, Formiga F, López-Soto A, Fernández-Moyano A, et al. Inappropriate prescribing to older patients admitted to hospital: a comparison of different tools of misprescribing and underprescribing. Eur J Intern Med. 2014 [cited 2016 Jan 10];25:710–6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25179678.

Higashi T. The quality of pharmacologic care for vulnerable older patients. Ann Intern Med. American College of Physicians; 2004 [cited 2016 Jan 10];140:714. http://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=717420.

Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. [cited 2015 Aug 21];163:2716–24. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14662625.

Hill-Taylor B, Walsh KA, Stewart S, Hayden J, Byrne S, Sketris IS. Effectiveness of the STOPP/START (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the Right Treatment) criteria: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41:158–69.

Levi Marpillat N, Macquin-Mavier I, Tropeano A-I, Bachoud-Levi A-C, Maison P. Antihypertensive classes, cognitive decline and incidence of dementia. J Hypertens. 2013 [cited 2016 Jan 10];31:1073–82. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23552124.

Schubert I, Küpper-Nybelen J, Ihle P, Thürmann P. Prescribing potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) in Germany’s elderly as indicated by the PRISCUS list. An analysis based on regional claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013 [cited 2015 Dec 30];22:719–27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23585247.

Jones SA, Bhandari S. The prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication prescribing in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease. Postgrad Med J. 2013 [cited 2016 Jan 10];89:247–50. http://pmj.bmj.com/content/89/1051/247.long.

Clínica G, Galega S, Interna DM, De E, Medicina S De, Complexo I, et al. Escalas de valoración funcional en el anciano. Galicia Clin. 2011;72:11–6. http://www.galiciaclinica.info/PDF/11/225.pdf.

San-José A, Agustí A, Vidal X, Barbé J, Torres OH, Ramírez-Duque N, et al. An inter-rater reliability study of the prescribing indicated medications quality indicators of the Assessing Care Of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) 3 criteria as a potentially inappropriate prescribing tool. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. [cited 2016 Jan 10];58:460–4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24438879.

Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(9):1136–9.

Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975 [cited 2015 May 20];23:433–41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1159263.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987 [cited 2014 Jul 10];40:373–83. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3558716.

Coca A, Aranda P, Bertomeu V, Bonet A, Esmatjes E, Guillén F, et al. Estrategias para un control eficaz de la hipertensión arterial en España. Documento de consenso. Rev Clínica Española. 2006;206:510–4.

Delgado Silveira E, Muñoz García M, Montero Errasquin B, Sánchez Castellano C, Gallagher PF, Cruz-Jentoft AJ. [Inappropriate prescription in older patients: the STOPP/START criteria]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2009 [cited 2015 Nov 11];44:273–9. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0211139X09001310.

Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller KE. Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods. Boston: PWS-Kent Pub. Co; 1988.

Formiga F, Vidal X, Agustí A, Chivite D, Rosón B, Barbé J, et al. Inappropriate prescribing in elderly people with diabetes admitted to hospital. Diabet Med. 2015 [cited 2015 Dec 4]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26333026.

Banegas JR, Navarro-Vidal B, Ruilope LM, de la Cruz JJ, Lopez-Garcia E, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, et al. Trends in hypertension control among the older population of spain from 2000 to 2001 to 2008 to 2010: role of frequency and intensity of drug treatment. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015 [cited 2016 Jan 10];8:67–76. http://circoutcomes.ahajournals.org/content/8/1/67.long.

Gu A, Yue Y, Argulian E. Age differences in treatment and control of hypertension in US physician offices, 2003–2010: a serial cross-sectional study. Am J Med. 2016 [cited 2016 Jan 10];129:50–58.e4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26299315.

Butt DA, Harvey PJ. Benefits and risks of antihypertensive medications in the elderly. J Intern Med. 2015 [cited 2015 Nov 26];278:599–626. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/joim.12446/full.

Coupet M, Renvoize D, Rousseau C, Fresil M, Lozachmeur P, Somme D. [Validity of cardiovascular prescriptions to the guidelines in the elderly according to the STOPP and START method]. Gériatrie Psychol. Neuropsychiatr du Vieil. 2013 [cited 2016 Jan 10];11:237–43. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24026128.

Campanelli CM, Fick DM, Semla T, Beizer J. Potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: the American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:616–31.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2014 [cited 2014 Oct 17];44:213–8. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4339726&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 [cited 2015 Oct 9];63:n/a–n/a. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26446832.

Moubarak G, Ernande L, Godin M, Cazeau S, Vicaut E, Hanon O, et al. Impact of comorbidity on medication use in elderly patients with cardiovascular diseases: the OCTOCARDIO study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012 [cited 2016 Jan 10];20:524–30. http://cpr.sagepub.com/content/20/4/524.short.

Galvin R, Moriarty F, Cousins G, Cahir C, Motterlini N, Bradley M, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing and prescribing omissions in older Irish adults: findings from The Irish LongituDinal Study on Ageing study (TILDA). Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014 [cited 2016 Jan 10];70:599–606. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3978378&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Gallagher P, Lang PO, Cherubini A, Topinková E, Cruz-Jentoft A, Montero Errasquín B, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of older patients admitted to six European hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 [cited 2016 Jan 10];67:1175–88. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21584788.

Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders-3 Quality Indicators. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(Suppl 2):S464–87. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01329.x.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Affairs and Equality for its financial support and Ailish Maher for revising the English in this manuscript.

Contributors:

PIPOPS Investigators Coordinating group: Antonio San-José (principal investigator), Antonia Agustí, Xavier Vidal, Cristina Aguilera, Elena Balların, Eulalia Pérez. Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (Barcelona): José Barbe, Carmen Pérez Bocanegra, Ainhoa Toscano, Carme Pal, Teresa Teixidor. Hospital San Juan de Dios de Aljarafe (Seville): Antonio Fernández-Moyano, Mercedes Gómez Hernández, Rafael de la Rosa Morales, María Nicolas Benticuaga Martínez. Hospital Clínic (Barcelona): Alfonso López-Soto, Xavier Bosch, María José Palau, Joana Rovira, Margarita Navarro. Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge (Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona): Francesc Formiga, David Chivite, Beatriz Roson, Antonio Vallano, Carme Cabot. Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez (Huelva): Juana García, Isabel Ballesteros. Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona): Olga H. Torres, Domingo Ruiz, Miquel Turbau, Paola Ponte Márquez, Gabriel Ortiz. Hospital Universitario Virgen Del Rocío (Sevilla): Nieves Ramírez-Duque, Paula-Carlota Rivas Cobas, Paloma Gil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The project was financed by Grant EC10-077 obtained in a request for aid for the promotion of independent clinical research (SAS/2370/2010 Order of 27 September from the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Affairs and Equality).

Conflict of interest

P. Ponte Márquez, O. Torres, A. San-José, X. Vidal, A. Agustí, F. Formiga, A. López-Soto, N. Ramirez-Duque, A. Fernández-Moyano and J. García-Moreno, J. A Arroyo and D Ruiz declare that they have no conflict of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Pharmacological Anamnesis

See Fig. 1 for the questionnaire used for pharmacological anamnesis.

Appendix 2: Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults

For the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults, see Tables 7 and 8.

Appendix 3: Screening Tool of Older People’s Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (STOPP)

The following drug prescriptions are potentially inappropriate in persons aged >65 years of age (see reference [12] for individual references below):

A. Cardiovascular system

Item 3. Loop diuretic as first-line monotherapy for hypertension (safer, more effective alternatives available) [Williams et al. 2004]

Item 4. Thiazide diuretic with a history of gout (may exacerbate gout) [Dougall and McLay 1996].

Item 5. Non-cardioselective beta-blocker with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (risk of increased bronchospasm) [van der Woulde et al. 2005, Salpeter et al. 2005]

Item 6. Beta-blocker in combination with verapamil (risk of symptomatic heart block) [BNF 2006]

Item 7. Use of diltiazem or verapamil with NYHA class III or IV heart failure (may worsen heart failure) [BNF 2006]

Item 8. Calcium channel blockers with chronic constipation (may exacerbate constipation) [Dougall and McLay 1996]

G. Endocrine system

Item 2. Beta-blockers in those with diabetes mellitus and frequent hypoglycaemia

H. Drugs that adversely affect fallers

Item 4. Vasodilator drugs with persistent postural hypotension, i.e. recurrent >20 mmHg drop in systolic blood pressure (risk of syncope, falls) [Leipzig et al. 1999]

Appendix 4 Screening Tool to Alert Doctors to Right Treatments (START)

These medications should be considered as appropriate and indicated for people >65 years of age with the following conditions, where no contraindication to prescription exists (see reference [12] for individual references below):

A. Cardiovascular system

Item 4. Antihypertensive therapy where systolic blood pressure consistently >160 mmHg [Williams et al. 2004, Papademetriou et al. 2004, Skoog et al. 2004, Thenkwalder et al. 2005]

Item 6. ACE inhibitor with chronic heart failure [Hunt et al. 2005]

Item 7. ACE inhibitor following acute myocardial infarction [ACE Inhibitor Myocardial infarction Collaborative Group 1998, Antman et al. 2004]

Item 8. Beta-blocker with chronic stable angina [Gibbons et al. 2003]

F. Endocrine system

Item 2. ACE inhibitor or ARB in diabetes with nephropathy, i.e. overt urinalysis proteinuria or microalbuminuria (>30 mg/24 h) ± serum biochemical renal impairment* [Sigal et al. 2005]

*Serum creatinine >150 µmol/l, or estimated glomerular filtration rate <50 ml/min [BNF 2006].

Appendix 5: Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders-3 (ACOVE-3) Quality Indicators [41]

Abbreviations ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, BP blood pressure, HF heart failure, HTN hypertension/elevated BP, IHD ischaemic heart disease, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, MI myocardial infarction, NSTEMI non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, VE vulnerable elder.

5.1 Hypertension

5.1.1 Intervening for Persistent HTN

Item 9. IF a VE with HTN has persistent (on two consecutive visits) systolic BP above goal*, THEN an intervention (e.g. pharmacological, lifestyle, compliance) should occur, or there should be documentation of reversible cause or other justification for the elevation.

*Goal systolic BP (mmHg): diabetes mellitus or chronic renal disease 130 mmHg; home ambulatory monitoring 135 mmHg; all other patients 140 mmHg of other specified goal.

5.1.2 Beta-Blocker for HTN and IHD

Item 13. IF a VE with HTN has IHD, THEN treatment with a beta-blocker should be recommended or there should be documentation of why it should not be provided.

5.1.3 ACE Inhibitor for Comorbid Vascular Disease

Item 14. IF a VE with HTN has a history of HF, left ventricular hypertrophy, IHD, chronic kidney disease or cardiovascular accident, THEN he or she should be treated with an ACE inhibitor or ARB or there should be documentation of why it should not be provided.

5.2 Heart Failure

5.2.1 ACE Inhibitor

Item 1. IF a VE has LVEF less than 40%, THEN he or she should receive an ACE inhibitor (or ARB if ACE inhibitor intolerant).

5.2.2 Selective Beta-Blocker

Item 7. IF a VE has HF and LVEF less than 40%, THEN he or she should be treated with a beta-blocker known to prolong survival (carvedilol, metoprolol, or bisoprolol).

5.3 Ischaemic Heart Disease

5.3.1 Early ACE Inhibitor Therapy for MI and HF

Item 5. IF a VE has an MI (STEMI or NSTEMI) complicated by HF or LVEF less than 40%, THEN he or she should be given an ACE inhibitor or ARB within 36 h of presentation and advised to continue this treatment for 4 weeks or longer.

5.3.2 Beta-Blocker Therapy

Item 14. IF a VE has had an MI (STEMI or NSTEMI), THEN he or she should be offered a beta-blocker and advised to continue treatment for 2 years or longer after infarction.

5.3.3 ACE Inhibitor Therapy

Item 15. IF a VE has IHD, THEN he or she should be offered ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy and advised to continue the treatment indefinitely.

5.4 Diabetes Mellitus

5.4.1 Proteinuria

Item 4. IF a VE with diabetes mellitus has proteinuria, THEN an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be prescribed.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Márquez, P.H.P., Torres, O.H., San-José, A. et al. Potentially Inappropriate Antihypertensive Prescriptions to Elderly Patients: Results of a Prospective, Observational Study. Drugs Aging 34, 453–466 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0452-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-017-0452-z