Abstract

We used qualitative in-depth interviews to evaluate the effects of a mass media climate change program on audiences’ efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, emotional responses, and motivations and intentions to address climate change. We conducted in-depth interviews with 73 participants from five US cities and three political parties who had watched episodes of the documentary television series, Season Two of Years of Living Dangerously. Eligible participants completed an in-depth interview within 24 h of viewing a select episode. Data were transcribed and then coded and analyzed using QSR NVivo 10. Weak efficacy beliefs limited intentions to enact concrete behavioral change. Outcome expectations, national-level actions, imagery, and emotional responses to stories played an important role in these processes. Explicit information about expected outcomes of various actions, and specifically successes, should be provided in order to boost efficacy and incentivize behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Swift action on climate change at national and international levels is necessary to achieve the level of mitigation required to prevent significant public health impacts. However, political and public action to address climate change has not grown in parallel with the scientific consensus and concern (Cook et al. 2016; Leiserowitz et al. 2013, 2014, 2017a). In the USA, one of the world’s most significant polluters, a lack of policy advances to address climate change has become a common discussion in media and national political dialogue (for example, see Rich 2018 and Meyer 2018). Although surveys of climate change attitudes and beliefs in the USA have shown that concern about climate change has been increasing over time, those same surveys demonstrate that personal-level action is limited. Only approximately 10% of Americans have participated in political activities to urge action on climate change (Leiserowitz et al. 2013) and only 11% make a lot or a great deal of effort to reduce global warming (Leiserowitz et al. 2017b), while a more recent survey shows that 22% believe we will not reduce global warming because people are unwilling to change behavior (Leiserowitz et al. 2018).

Scholarly attention to climate communications and climate change in media has grown in recent decades (Boykoff and Roberts 2007; Schäfer and Schlichting 2014) as scholars continue to ask how to engage the public about climate change. However, the growth of this body of literature in the USA has been slower than in countries such as the UK and Sweden. Additionally, only approximately 1.5% of these studies have investigated the efficacy of film or documentary as climate communication modalities (Schäfer and Schlichting 2014). Given the potential for this form of mass media to reach a wide-ranging audience, there is a need for more focused efforts to evaluate the potential impacts of climate communications through film media on personal behavior change and participation in collective and political action (Carvalho et al. 2017; Lakoff 2010; van der Linden et al. 2015).

Climate change documentaries have become a popular tool to reach audiences in efforts to elevate concern and stimulate action on climate change. This is highlighted in part by recent high-profile programs such as Years of Living Dangerously, an Emmy Award–winning series that was aired on two popular cable networks; Before the Flood, Leonardo DiCaprio’s award-winning documentary film that is estimated to have reached 60 million viewers; and An Inconvenient Truth, which remains in the list of top five grossing Global Warming videos on Box Office Mojo (Gerard 2016; “Global Warming” 2018). Existing research demonstrates that film has a unique potential to promote both individual and collective climate action through a combination of imagery, narrative storytelling, and celebrity messengers in both cognitive and emotional appeals (Manzo 2017). Studies of films such as An Inconvenient Truth, Gasland, and The Age of the Stupid demonstrate this potential (Beattie et al. 2011; Cooper and Nisbet 2016; Howell 2011, 2014; Jacobsen 2011; Manzo 2017; Nolan 2010), although longer term impacts are unclear (Howell 2014).

In this study, we add to this growing body of literature by turning attention to Years of Living Dangerously (Years). The first season, which contained nine episodes, aired on Showtime in 2014. The second season, containing eight episodes, aired on National Geographic in 2016. Understanding if and how climate change documentaries impact audiences is important because high-profile films or documentaries like this have the ability to reach a wide-ranging audience. A notable example of this is An Inconvenient Truth. It is the fifth highest “Global Warming” grossing film, following only major fictional blockbusters like The Day After Tomorrow (“Global Warming” 2018).

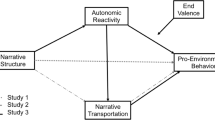

Our central research question asks how audiences respond to Years episodes and how these responses affect audience motivations to take action on climate change. To this end, we assess how a diverse sample of Americans responds to Years, paying specific attention to the connection between concern, efficacy beliefs, emotion, motivation, and intentions (Ajzen 1991; Bandura 1986; Cooper and Nisbet 2016; Green and Brock 2000; Moyer-Gusé and Nabi 2010; Nabi et al. 2018; Ojala 2015; Slovic and Peters 2005). Before turning to the details of this study, we briefly review the literature relating to efficacy, emotion, and stimulating action. We also briefly review literature on climate change documentaries with a focus on their role in addressing key barriers to individual action on climate change (whether that is individual behavior change, political behavior, or collective action).

2 Conceptual background

2.1 Barriers to action, efficacy, and emotion

Efficacy beliefs are a key construct in prominent theories of behavioral change. Social cognitive theory (Bandura 1986) defines efficacy beliefs as people’s confidence in their abilities to exert personal control. Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior (TPB) also emphasizes the importance of efficacy beliefs in the formation of behavioral intentions through a construct called perceived behavioral control (Ajzen 1991). Climate change communications and survey research suggest that weak efficacy beliefs are a continued barrier to engagement with climate change (Lorenzoni et al. 2007; Roser-Renouf 2014). Perceptions of issue importance and concern about climate change have increased in recent years (Leiserowitz et al. 2015, 2018). However, of those who think global warming is happening, more than 50% feel hopeless about the issue. Even people concerned about climate change are often unsure about what they can personally do to address it (Semenza et al. 2008). This problem is further exacerbated by a general lack of knowledge about potential solutions to the problem, a finding supported by studies that show that few concerned people participate in behaviors, such as contacting government officials (Doherty and Webler 2016; Leiserowitz et al. 2013; Roser-Renouf 2014).

Further, the relationship between outcome expectations and self-efficacy beliefs may be an important consideration for understanding how intentions to participate in climate action develop (Ajzen 1991; Bandura 1982; Strecher and DeVellis 1986; Williams and Bond 2002). While people generally identify the importance of individual action in mitigation, they also believe their personal action would not be sufficient to make a difference in fighting climate change (Lorenzoni et al. 2007). As a result, scholars have suggested reframing climate change to focus on gain frames, solutions and development, and not just impacts (Feinberg and Willer 2011; Maibach et al. 2010; Nisbet 2009; Spence and Pidgeon 2010). Koletsou and Mancy (2011) suggest that individuals must believe participation in a collective action will achieve some goal because of the individual’s participation in that action (personal outcome expectancy) in order to participate (Koletsou and Mancy 2011). Additionally, individuals must believe that collective action is capable of achieving a goal (collective outcome expectancy). Roser-Renouf et al. (2014) further support this claim by providing evidence that perceptions of collective efficacy predict climate activism (Roser-Renouf et al. 2014). For climate change communicators, low efficacy beliefs are of particular concern because as Witte and Allen (2000) demonstrate, low efficacy combined with high levels of concern or risk perceptions (which may result from the demonstration or experience of climate impacts) can lead people to reduce fear through coping mechanisms as opposed to taking action to reduce the threat (Witte 1994; Witte and Allen 2000). These studies emphasize the importance of balancing threat with efficacy and hope in communicating about climate change and in efforts to stimulate participation in climate action.

Emotional engagement is particularly relevant for narrative communications such as documentary film because of its critical role for decreasing counter-arguing and increasing involvement with a given narrative (Green et al. 2004; Moyer-Gusé and Nabi 2010). Emotional appeals through imagery can increase risk perceptions and salience (Manzo 2010; Metag et al. 2016; O’Neill et al. 2013; O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole 2009). Recent scholarship suggests that emotion plays a critical role in climate-related efficacy beliefs. Smith and Leiserowitz (2014) demonstrated that discrete emotions, interest, hope, and worry were strong predictors of mitigation policy support (Smith and Leiserowitz 2014). Feldman and Hart showed that fear and hope have important mediating roles in the relationship between efficacy messaging and political activities like climate activism or participating in regulatory public comment periods, depending on political affiliation and the type of activity (Feldman and Hart 2016). Response efficacy was particularly important for this relationship among conservatives. Most recently, Nabi et al. (2018) have begun to assess the impacts of emotional processing on efficacy beliefs through testing of a theory of emotional flow. They argue that that intensity of emotional response to a message carries over to responses to subsequent messages. Nabi and Green (2014) additionally argue that changes in the emotional state across a narrative are important for persuasion and continued engagement with a narrative after exposure to the initial message (for instance with a television series) (Nabi and Green 2014). Emotional flow is particularly relevant for film media because of the development of a complex narrative over time. There is a need to assess how climate change documentaries impact emotion and to provide further context regarding the relationship between efficacy beliefs, emotion, and motivations and intentions in audience responses. Understanding which elements of climate change documentaries are most successful in evoking particular types of emotions could be useful in increasing the efficacy of storytelling.

Finally, celebrities may have an important role in generating interest in the issue as they have become increasingly prominent voices in climate and environment discourse (Anderson 2011; Boykoff et al. 2010; Doyle et al. 2017). However, there is also some evidence that the use of celebrities can undermine salience (O’Neill et al. 2013). While not the focus of this current study, further assessment of how celebrity-driven narratives, in particular, are helpful or present obstacles to viewer engagement is critical given the increasing reliance on the celebrity messenger in climate films.

2.2 Documentary film and climate change

Film media can combine multiple communication strategies, including the use of opinion leaders, imagery, and scientific information and narrative to employ both cognitive and emotional appeals in the address of barriers to engagement. In that way, climate change films may be uniquely situated to encourage engagement. The capacity of film to combine imagery, narrative, and music gives it the potential to emotionally engage audiences as well as provide information (Manzo 2017). But there is little research exploring how it helps audience’s engagement with the issue and generates motivation to act.

Several prominent non-fiction, pro-climate, and environmental action films have received scholarly attention. The two most prominently studied documentary films are An Inconvenient Truth (AIT) (USA) and The Age of the Stupid (AS) (UK). AIT (2006) shows Al Gore, former Vice President of the USA, giving a presentation about climate change in the format of a slideshow. AS (2009) is unique in that it combines documentary and fiction. While it is set in the future, six documentary storylines of present-day are interwoven that demonstrate dependence on fossil fuel from the perspective and individuals’ stories.

Assessments of AIT demonstrate that it impacted emotions like happiness, sadness, and anger; increased motivation to do something about climate change; and influenced changes in behavior at least in the short term (Beattie et al. 2011; Jacobsen 2011; Nolan 2010). For example, Beattie et al. (2011) demonstrated that clips of AIT generally decreased happiness and increased sadness and anger but increased motivation and empowerment. Jacobsen (2011) showed that AIT was associated with purchases of carbon offsets. Howell’s work shows that AS increased concern, motivation, and efficacy; however, these changes did not persist for more than a couple of months after watching the film. Additionally, respondents reported changes in behavioral intentions due to the film, including reducing air travel (Howell 2011). While not about climate change alone, a study of Gasland, a documentary about fracking, provides further support for the ability of this genre to impact information-seeking behaviors, social media involvement, and social mobilizations (Vasi et al. 2015).

We seek to further the above literature in this paper, by taking an in-depth qualitative approach to understand how climate change documentary and the Years, in particular, affects key audience responses and their relationship to climate action, focusing on efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, emotions, and intentions. We also assess how audience ideation of climate action may affect these factors.

3 Data and methods

Years of Living Dangerously (Years) is a documentary television series that features celebrities investigating how climate change affects humanity. Storylines take viewers all over the world and around the USA to show how prevailing climate change issues are being experienced. A celebrity correspondent hosts each story about a specific climate change issue, such as deforestation and rising sea levels. Years of Living Dangerously was chosen as a case study due to its high-profile nature in the USA, its focus not only on impacts but on solutions and action, and the scale of investment in its serial production and resultant opportunities for exposure. Years had several goals: to “tell the human story of climate change…as opposed to telling the story of climate change as some kind of distant, far-off problem,” tell stories about impacts and solutions like political action and technology, to increase the profile of the issue, tell “emotionally gripping storytelling, where you really get invested in characters and their stories” in order to encourage people to act, and to this cinematically (by being “visually exciting”) (Joel Bach in Meyer 2015). This study is based on data from one component of a four-part evaluation on media effects of the Years series which aims to not only assess the research question laid out above but to evaluate whether or not years met some of these goals. The qualitative study design and methodology are described in detail below.

3.1 Case selection and description

We selected four episodes from Season Two of the Years. Season Two was selected instead of Season One in order to make the issues as timely and relevant as possible. Each episode features two stories. Four episodes were selected to include variation across climate issue and geographic locale. The stories in the four episodes vary by type of climate issue, location of story, and focus on actions and solutions to address the climate issues. Episode one, “A Race Against Time” of Years, follows two stories. Story abbreviations to be used from here forward are indicated for each storyline after the description. First, David Letterman follows a quest to find out how India is developing solar energy, interviewing local families and Prime Minister Modi, among others (Solar India). That story is intercut with another story featuring Cecily Strong where she investigates how the utilities have misled the public about the costs of solar power in the USA (Solar USA). Episode two “Priceless” features a story where two college students and Nikki Reed try to get other students to have their universities support a carbon pricing plan (Student Organizing), while Aasif Mandvi explores how species are going extinct around the world, and especially in Africa, due to climate change (Extinction). The third episode “Uprising” features Sigourney Weaver in Hong Kong exploring China’s economic growth, introduction of renewables, and protests of government efforts to support fossil fuels (Coal China), and a storyline where America Ferrera helps community leaders in the Midwest protest a coal-fired power plant (Coal USA). The fourth episode, “Fueling the Fire,” features Giselle Bündchen investigating the drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon (Deforestation), and Arnold Schwarzenegger in Kuwait seeing how oil is burdening the US military (Oil) (Years of Living Dangerously Season Two2016). These episodes focus on potential solutions to climate change and create a dialogue between the characters and celebrity correspondents about the feasibility of the solutions. They additionally show everyday people participating in actions to support those solutions, mainly in the form of community organizing, protest, and changing dietary habits. Each episode is just under an hour long.

3.2 Data collection

We conducted one-on-one in-depth interviews (N = 73) in order to explore the influence of Years on the formation of climate change–related efficacy beliefs and behavioral intentions. We recruited participants through geographically targeted Facebook, Craigslist, and mTurk advertisements using a combination of convenience and quota sampling. Interviewees were selected in five cities, each representing a region of the USA: Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Miami, Florida; Toledo, Ohio; Las Vegas, Nevada; and San Francisco, California. Interview sites were chosen based on political significance in the 2016 Presidential election in the USA, variance in political orientation, race, socioeconomic status, diversity of exposure to climate change risks, and proximity to a location featured in a storyline in one of the selected Years episodes. Individuals were screened with a brief pre-interview survey to make sure they met a minimum age of 18 and that there was variation in age and political affiliation. Eligible participants scheduled an interview time and were sent a link to watch one of four episodes in the 24 h prior to the scheduled interview. In-person or Skype interviews occurred during January, February, and March of 2017. The interviews initially asked questions about participants’ thoughts and understanding about climate change, if they had seen Years previously and then transitioned to asking about reactions to what they saw, their likes and dislikes, their risk perceptions and interest, motivation and plans to take action, and their perceptions of how the documentary impacted those reactions.

The sample is described in Table 1. While there is variation in thought on the number of interviews required to reach saturation, 12 interviews should be sufficient for saturation and themes may be established as early as 6 interviews (Guest et al. 2006). Given that we have a minimum of 12 interviews per location, we did not have difficulty reaching saturation.

Prior to the interview, participants received a link to watch one of the four episodes from Season Two of Years in their home 24 h in advance of the interview. Participant interviews were audio recorded to uphold the integrity of the data collection process. Participants received $100 for their participation in the qualitative study.

3.3 Data analysis

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed and then analyzed in NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software by QSR International. Qualitative data were analyzed according to framework analysis (Smith and Firth 2011). The codebook assessed audience reactions on a variety of factors including efficacy beliefs, motivations to act, risk perceptions, and behavioral intentions (see supplementary material). The literature review and research questions guided initial analysis. We used inductive coding to refine the coding structure after the first 10% of the interviews. However, after initial coding structure adjustment to ensure accurate capture of data themes, the rest of the data were deductively coded according to the finalized coding structure. Two researchers were involved in coding transcripts; however, one researcher primarily completed all coding. Two researchers coded a 10% sample of the interviews (Campbell et al. 2013). We then assessed inter-coder reliability with NVivo 10, which provides Cohen’s Kappa statistic. An average Cohen’s Kappa was derived from the statistics provided for each node for each source. The average Kappa statistic was .958. Thereafter, one researcher completed coding. All uncited quotes are extracted from select interviews.

4 Results

4.1 Personal-level barriers and action ideation

After watching Years episodes, participants had high levels of concern about climate change, but generally low perceived susceptibility to climate change risks. Storylines and imagery demonstrating the impacts of air quality on human health (“Uprising”), the role of drought in mass extinction events (Extinction), and the scale of deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest (Deforestation) were particularly impactful elements for elevating concerns about climate change. However, participants rarely discussed or identified their own personal vulnerability to climate change risks. Some of these images also invoked fear. For some participants, the imagery of mass extinction (Extinction) in particular was over the top and evoked perceptions of fear mongering.

When asked about behavioral intentions after watching Years, participants often responded with uncertainty about what they could do beyond what they already do. In general, behaviors that participants reported engaging in to address climate change included routine behaviors such as recycling, turning off lights and water when not in use, and using public transportation. Engaging in a behavior or taking a particular action in the past gave participants a sense of efficacy for continuing those behaviors or taking additional action in response to what they saw. Some participants had a sense of efficacy for doing routine individual-level behaviors such as recycling, conserving energy, and driving less, which are largely behaviors that they were already doing as part of their daily lives. Participants largely framed these routine behaviors as environmentally friendly behaviors that they are already doing. Fewer participants had a sense of efficacy for political actions. Some political behaviors such as voting or providing signatures on petitions were also mentioned, although these behaviors were mentioned much less frequently and were also usually mentioned by participants who had watched an episode that highlighted this particular type of involvement in climate action (“A Race Against Time”) and had participated in this type of action in the past. This was also the case with intentions for future actions which may indicate that participants’ ideation of climate action is typically limited to individual behaviors in the personal sphere (in particular, activities they have already participated in), as opposed to outward-facing behaviors such as collective or political action.

The primary barrier to action discussed was not knowing what to do or where to start. On this front, self-efficacy was low in our sample. We heard several explanations for lack of efficacy in addressing climate change. They included perceived personal-level barriers, a lack of national-level action, and lack of a feeling of collective efficacy. Some specific barriers mentioned have been previously reported in the climate change literature. These personal-level barriers included lack of interest, lack of mobility, difficult family situations, lack of time, lack of financial flexibility, lack of resources at school, lack of clout, lack of decision autonomy (being part of a home owner’s association or living in an apartment), lack of public transportation, and politicization of the issue. In reaction to a storyline in the “Priceless” episode where a college student is shown to be organizing on campus and traveling to Canada to speak with a local politician, one participant stated:

I mean, I have a problem where I want to do things but then I can’t think of how to actually accomplish them so that’s probably what this video did. I mean we don’t really have anything like that at ____ like what that guy had, like with that student council, we don’t really have anything like that. (Democrat, Toledo, Student Organizing)

The primary barriers demonstrated in the storyline about the solar power industry in the USA is collective action, protesting and signing petitions, but participants sometimes focused on barriers to personal installation of solar power. One participant said:

The information is empowering, but I’m disempowered in that, what can I do about it? I rent an apartment so I can’t go out and get solar. (Independent, Portsmouth, Solar U.S.)

Interviewees generally lacked a feeling that they could engage in specific behaviors, primarily because they were unsure of what actions to take beyond current behavior. One interviewee expressed:

There was frustration like what I said. About the knowledge being power but what do we do next. All of these call to actions, what do I do next but I don’t know what to do and no one knows what to do (Democrat, San Francisco, “A Race Against Time”).

We found that individuals’ efficacy was related to the larger context in which participants lived. Interviewees often felt that the problem of climate change was so large that they would be unable to make a difference. Despite the Years narratives of individuals participating in specific actions as champions for change, the impact of their own behaviors was viewed in the context of perceptions of (in)action by others. This undermined the willingness to change. One interviewee said:

It’s obviously going to take a huge number of people to change and affect how like how we get our energy and affect like reducing climate change. I feel like one person obviously can’t have that much of an effect when you have everybody else doing something different. (Republican, Toledo, “A Race Against Time”)

Similarly, another interviewee said:

If one person wants to put solar panels on their house, that is great they are taken off the grid, but you have how many other like millions of people without solar panels so they are still using coal and natural resources rather than renewable. That one person is not going to really have an effect. (Republican, Toledo, “A Race Against Time”)

As another example:

If I see any petitions I will do something. I don’t really know what I can do as not being a politician and being a singular person. I don’t know what I can do and affect by myself. (Independent, Las Vegas, “A Race Against Time”)

4.2 Perceptions of collective action and need for specific strategies

The need for collective action also included governmental action both in the USA and internationally. Individual interviewees linked their feelings of personal inability to act after watching a video to the need for national government action and to the need for action in other countries. However, challenges to individual-level action were further exacerbated by a lack of understanding regarding how to engage in political or collective action and the need for specific instructions on how to address climate change at the individual level. One interviewee said:

It made me less empowered because I am not in control of the government and they are the ones that have the control to stop. If they are truly good people and they care about us, they can make it stop and definitely can if they can stop the big companies from benefiting. If a few people don’t want to stop eating meat, then the government has to do something about it. (Democrat, San Francisco, Deforestation)

This reaction stemmed from the framing, in multiple episodes, of individuals fighting against state or national governments for change. This framing may signify to audiences that policy-level change is the measure for success and is needed to achieve the desired goal. While these narratives may be hoping to stimulate participation in collective or political processes, they may also have the unintended effect of decreasing efficacy beliefs by highlighting the challenges individuals face when petitioning governments and failing to demonstrate a positive outcome. For instance, only one of the storylines demonstrated clear, positive outcomes from the actions of the characters. In that story, a college student’s conservative family agrees to support his efforts to advocate for a carbon tax. However, none of the other storylines show concrete outcomes beyond the characters’ participation in actions such as attending meetings, canvasing, or giving advocacy presentations. This connection between self-efficacy, empowerment and expectations for outcomes of social or political action, was a common theme across interviews.

Feelings of lack of control over what happens in other countries further had similar effects. One participant said:

On the rainforest side, how much can we do since it is in a country that we aren’t in? Besides the whole part where people could stop and become more vegetarian like more vegan and stop with the meat production and the importing. In general, are you going to tell people that go to In-N-Out Burger? (Democrat, Las Vegas, Deforestation)

Another interviewee qualified what might facilitate taking political action:

… that it would be nice to have some support or group at our college that would support these things. I don’t feel as driven to go advocate for these things on my own. (Democrat, Toledo, Student Organizing)

Although interviewees claimed the need for collective action to motivate their own action, portrayals of collective action were ineffective in instigating self-efficacy for several reasons. Stories in Years included groups of people organizing, demonstrating, and utilizing resources at institutions like non-profits and universities to circulate petitions and initiate contact with political officials. Even this type of action seemed complex and inaccessible to the average American in our sample who lacked familiarity with the political system or resources with which to organize. These activities may seem simple but many of our participants desired more explicit guidance about what types of things they could do to make a difference. In particular, for political behaviors, because most people’s only interaction with the political system is through voting, the actions demonstrated in the Years episodes (for example, organizing, canvasing) may still seem difficult or inaccessible. This suggests a disconnect between the types of actions portrayed in the video and the types of actions Americans feel able to do on their own. One interviewee described his reaction to the story about air pollution in China:

I was waiting for the black screen to show what you are going to do or whatever…I am saying ya know I think that there was a lot of valuable information but it didn’t push an inspiration to go further in which I felt it could have done. (Democrat, Portsmouth, Coal China)

For other participants, this impact manifested in an understanding that collective action was necessary. One Republican participant did not believe that his individual actions, like changing types of light bulbs used, mattered, but he recognized the importance of lobbying government officials to enact change.

We did not see much evidence of positive outcome expectations; people’s beliefs that taking particular actions will result in favorable outcomes they seek, in our data, either after watching the episode or in their normal day-to-day lives. We found that viewers wanted to better understand the ramifications of their actions as a form of motivation for taking additional steps. For example:

If someone came to me and said that you’re driving a Tesla or a Prius and says they are saving the world, I would say you’re not because you could drive 10 Tesla’s and it is not going to change the fact that for every 1 Tesla you have there are 1,000 tanks. You are climbing uphill and you’re not making a significant enough change. It did enlighten me but it didn’t pivot my behavior. (Republican, San Francisco, “Fueling the Fire”)

Although Years episodes present storylines that show particular types of actions taking place, interviewees pointed out that the results of those actions are not discussed. This caused participants to question the action. One Republican participant identified that many people have low self-efficacy because there is a lack of information about what people can do to make an impact in their day-to-day lives, accompanied by information about what impact those behaviors will have. Similarly, some participants also expressed frustration at not knowing what happened next in the stories portrayed.

Further evidence to support the importance of understanding possible outcomes in consideration of behavioral investment was demonstrated by some participants who expressed interest in knowing how much money would be saved by adopting solar, while others expressed interest in knowing what happened as a result of activist behaviors demonstrated in Years. Outcomes of particular actions are not being shown or discussed in these episodes or other types of climate change communications. Importantly, results of actions should also be relatable and understandable to a non-technical audience. One interviewee said:

One of the guys in India was like ‘if we do all this it will save eighty billion or eighty million tons of carbon,’ I’m going, I don’t know how much carbon causes a degree, it’s just a number. I don’t care about that fact. I mean I do but I don’t…it doesn’t have any meaning to me. It’s not like, you know, for every, if it was something where every eighty billion parts of CO2 makes one degree hotter, I mean one degree hotter doesn’t really reflect, but at least I kinda get an idea at least as a figure. (Republican, Miami, Solar India)

In the next section, we describe evidence of factors and approaches utilized in Years that positively influenced efficacy beliefs and discuss the influence of emotion.

4.3 Emotion, efficacy, and action

Specific story elements in the documentary influenced emotion. Participants described imagery, the presence of everyday people, and depictions of political challenges as primary elements that impacted emotions. Imagery was critical for engaging the audience. Participants frequently mentioned being shocked by the imagery of the scale of deforestation in Brazil which was shown from the birds-eye-view of a helicopter and maps (Deforestation). Imagery of pollution in China and Illinois raised concerns about health (Coal USA). Only one particular storyline generated strong reactions of fear, a story of drought in Africa and imagery of mass extinction (Extinction). The imagery and music seemed to be a significant factor in the development of fear and sadness. However, while some participants reacted with fear, others felt like through the extreme imagery, the video was fear mongering. The stories of everyday people taking action in Illinois (Coal USA) and in Texas (Student Organizing) were important for engaging participants in the story. They liked witnessing everyday people engaging with the issue, talking about why it was important, and then taking action. Particularly for the story about the college student advocating for carbon pricing in “Priceless,” some participants experienced feelings of hope by seeing the engagement and passion of young people. However, some of these stories were also met with frustration because the outcomes of their efforts were hardly discussed or were negative.

The “Uprising” and “Race Against Time” episodes on coal and solar power respectively generally led to anger and shock at the depicted dichotomy between action outside of the USA (in China and India, respectively) and political and corporate barriers to action within the USA. Viewers expressed greater interest in political behaviors in response to these episodes than in response to the Deforestation and Carbon Pricing episodes. These episodes framed the international stories as challenges and did not showcase the same contrast between implementation of action or policy like the other two episodes did. For example, in response to “A Race Against Time” which contrasts solar power development in India with political challenges to solar development in the USA, one participant said: “I would like to know, like yeah, I mean I would want to lobby my state reps as to go ‘hey why, why is FPL so...awful.’” (Republican, Miami, Solar USA). This particular participant may also have had lower perceived barriers to political involvement based on past political experiences.

Alternatively, people who primarily experienced sadness, hopelessness, depressive feelings, or apathy were less likely to want to act. One interviewee said:

It is very frustrating. It is a feeling of hopelessness. You start to think about why people don’t think of these things as much and that is because if you do, what can you really do? (Democrat, San Francisco, “A Race Against Time”)

For this participant, the issue of climate change and the political challenges to solar development in the USA lead to feelings of hopelessness.

Emotion appeared to play a critical role in impacting action in several ways. First, participants who had strong emotional reactions to Years (usually instigated through the dramatic imagery or compelling storylines) tended to express more concern about climate change than did those who did not have as strong emotional reactions. Second, in general, participants who experienced prevailing and strong emotions of anger, shock, and optimism more often expressed interest in taking action to address climate change. Additionally, participants who experienced these types of emotions were usually more confident in their own desire and ability to take action. Third, emotions like hopelessness, depressive feelings, and apathy were often accompanied by lack of motivation or beliefs about ability to make an impact by taking action. Fear and general concern seemed to generate interest in the issue but it was difficult to assess any relationship with action. This is in part due to the fact that most participants did not report strong reactions of fear. While participants did express being worried about climate change, most participants reported the emotions mentioned above when prompted to reflect on their feelings about what they watched. This could in part be due to the fact that these episodes did not focus primarily on impacts but also included extensive attention to solutions and action. Due to our study design, it is difficult to associate positive (or negative) emotions with greater (or lower) intentions and even less so actions. It is clear, however, that particular stories and imagery in Years episodes garnered specific emotions.

5 Discussion

Climate change documentaries are becoming a popular tool to reach wide-ranging audiences in efforts to elevate concern, raise the prominence of the issue in political dialogue, and stimulate action. We aimed to assess how a climate change documentary influenced audiences’ efficacy beliefs and motivations to take action on climate change due to the importance of efficacy beliefs in the formation of behavioral intentions (Ajzen 1991; Bandura 1986), literature stressing the importance of efficacy and emotion for engagement with climate change (Nabi et al. 2018; Roser-Renouf 2014; Roser-Renouf et al. 2014; Semenza et al. 2008), and a need to understand how communication through film impacts these mechanisms.

Our findings demonstrate that documentary storytelling can generate concern and desire to take action. However, impacts on efficacy and intentions are more tenuous. After watching Years episodes, most participants reported feeling concern about climate change and expressed desire to do something about it after watching the documentary episodes. Despite this fact, few participants thought they had the ability to impact climate change or expressed intent to take concrete action after watching. For instance, little language describing intent was used by participants. Participants primarily used language like “I could” or “I would” instead of “I will” or “I plan to” when talking about their interest in action. Key factors that influenced participants’ efficacy beliefs and motivations included desire for more information about outcomes of action due to documentary’s lack of specificity in describing actions that individuals should take to address climate change, perceptions of collective action, and emotional responses.

We show that improving understanding of how individual actions affect specific outcomes could improve both a desire and a sense of ability to take action. This aligns with past work suggesting the importance of managing outcome expectations in managing efficacy beliefs (Ajzen 1991; Bandura 1986), particularly for social or collective action issues (Koletsou and Mancy 2011; Roser-Renouf et al. 2014). For our participants, a disconnect between an action and what such action could achieve hinders both motivations to take action and beliefs that taking that action would have an effect. This reaction stemmed from beliefs about the significant scale at which climate change operates and related skepticism about the impacts of individual-level behavior. A lack of specific ending to the stories portrayed also caused frustration among our participants. While telling stories without uncertain endings may make for interesting stories in other contexts (see Bach in Meyer 2015), does that strategy make for good climate change communications in situations where uncertainty is already high? Our results indicate that it may further complicate reactions to climate information.

Bandura’s social cognitive theory emphasizes the importance of both efficacy and expectations about a specific behavior. However, in complex social problems, like climate change, that require collective investment in addressing the problem, an individual’s efficacy beliefs about collective action are also important for policy support, political participation, climate activism, and environmental behaviors (Koletsou and Mancy 2011; Lubell et al. 2007; Roser-Renouf et al. 2014). Our results are similar to past findings (Lubell et al. 2007) that perceptions of policy elite competence are the strongest predictor of political participation since study participants recognized limits to individual action and stated that the government would take action “If they are truly good people and they care about us, they can make it stop.” This need for perceived collective and policy-level action highlights a challenge for storylines that take place abroad. For instance, our participants asked “what can I do” when watching the video about large-scale deforestation in Brazil and the political challenges to stopping the deforestation. They did not understand how they, as residents of the USA, could have an influence in a country where they cannot participate in collective or political action.

While demonstrating collective action in the USA interested audiences, it was generally not enough to positively impact efficacy beliefs. Beliefs about the limitations of collective actions usually stemmed from perceptions of political challenges or uncertainty about what an expected or positive outcome should be for a particular action. Another critical challenge is the lack of understanding of how to engage in political action. Audiences may not be familiar with the political system or have knowledge of resources available for organizing, which may reduce their ability to engage in change. Generally, when asked about behaviors, participants described individual habitual behaviors such as turning off lights and water and recycling as actions they participate in, and those who did had usually participated in this type of action previously. Few participants discussed participating in collective action, political action, or advocacy behaviors. While prominent messaging about environmental behaviors seems to have been internalized, perhaps as Carvalho et al. (2017) suggest, in order to generate more political and collective action, we must turn a focus toward those types of actions. As such, more explicit guidance and demystification about how to participate in political activities, such as contacting a representative via phone to talk about a particular issue, or collective activities may help make the first connection between the low efficacy audience and the inner-workings of the political system. This is an important point because simply showing others engaging in collective action (when the viewer does not know how to engage himself or herself in the same manner) does not appear to improve efficacy; more ominously, it may have a boomerang effect by convincing the viewer that he or she is incapable of doing what others are shown doing, resulting in tuning out the central message and internalizing low efficacy perceptions. Finally, those who reported participation in specific behaviors in the past were more likely to say that they would do those behaviors in the future in response to watching a Years episode. This may imply that behaviors can be the basis upon which additional behaviors are built and that understanding intended audiences’ environmental behaviors may be important for informing storytelling if the goal is to stimulate action.

Additionally, specific types of storytelling approaches stimulated emotions that were associated with interest in taking action. In this regard, our results are similar to past work (O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole 2009; Ojala 2012; Witte and Allen 2000). These studies demonstrated the importance of hope in engagement (Ojala 2012, 2015) and the limitations of fear in inducing behavior change (O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole 2009; Witte and Allen 2000). In our study, emotions of anger, shock, and optimism most often accompanied interest in action to address climate change. Hopelessness, depressive feelings, and apathy were often accompanied by lack of motivation or beliefs about ability to make an impact by taking action. Additionally, strong emotional reactions to the documentary appeared to be tied to concern about climate change. This aligns with work demonstrating the importance of emotion in narrative engagement and media enjoyment (Green et al. 2004; Moyer-Gusé and Nabi 2010) and more recent work from Cooper and Nisbet which demonstrates important nuances in the association between narrative engagement, affect, risk perceptions, and subsequent policy preferences (Cooper and Nisbet 2016). Finally, like recent work on the importance of emotion and efficacy (Feldman and Hart 2016; Nabi et al. 2018), emotion appeared to be connected to efficacy in that those who had strong emotional reactions that appeared to impact interested in taking action (anger and shock for instance) also appeared to be more confident in their desire and ability to take that action. In our study, participants reported experiencing variation in their emotional response over the course of watching the documentary based on specific moments of imagery or narrative. While we cannot evaluate how these factors translate to intentions for our participants or whether it is internalized to cause behavior, our results support the importance of considering emotional response as a critical element of engagement with climate communications and further evaluation of the impacts of discrete emotions and emotional processes. In particular, we echo previous suggestions of careful consideration of evoking emotions like fear and hopelessness (whether intentional or not) if aiming to boost efficacy beliefs and stimulate action (O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole 2009; Witte 1992; Witte and Allen 2000).

5.1 Recommendations for documentary filmmakers

We conclude this paper with a discussion of recommendations for filmmakers based on our assessment of reactions to these documentary episodes. Very explicit actions and their benefits must be articulated in order to impact motivation to change a behavior. This is grounded in behavior change theories like social cognitive theory and the theory of planned behavior. Efforts should be made to give specific information about how to participate in these types of action and focus on demonstrating success of these types of action. Depending on where the film is designed for broadcast (on television or on websites, for example), it may also be possible (and necessary) to direct audiences to and provide supplemental materials for viewers to learn more and learn about achievable and accessible opportunities for engagement. Further, demonstrating successful actions and explicating those in tangible and relatable terms is necessary so that the outcome has meaning for the audience. Finally, the importance of compelling stories and evocative cinematic imagery should not be ignored. Our participants found these elements particularly important for engagement and interest in the viewing experience which likely enhanced the attitude and behavior-related outcomes which aligns with work on the impact of emotion, enjoyment, and transportation on persuasive outcomes (Green and Brock 2000; Green et al. 2004; Nabi and Green 2014).

5.2 Limitations

This study utilized in-depth interviews to assess audience responses to documentary climate change narratives in detail. With 73 interviews, our study was a robust qualitative assessment of these episodes of Years. However, we only assessed four episodes of the second season of Years due to specific interest in those storylines, and desire to have at least 12 interviewees per episode (Guest et al. 2006). While it is difficult to generalize the results of these four studies to the remaining episodes of Years season two, this analysis provides critical information about remaining challenges to stimulating action through media as well as highlighting strategies that are effective at generating that interest. Along that same line, through this study design, we were not able to measure behavioral intentions or behavioral action beyond the time of the interview; therefore, we are unable to assess long-term impacts of these Years episodes. Finally, it is possible that social desirability bias prevented participants from correctly describing their own behaviors or caused them to provide answers that seemed more favorable to questions about their environmental behaviors and climate actions. However, most participants readily described a lack of efficacy, described barriers to engaging, and pointed out what they did not like about the documentary.

Given the political nature of climate change and the presence of prominent celebrities in Years, future work should assess the role of the politicization of climate change on audience response to documentary information and whether celebrity-driven narratives encourage engagement with the issue or create further obstacles.

Climate communications that depict large problems and highlight risks associated with them can have counterproductive effects by making people believe that the issue at hand is too complicated to be affected by individual action. It is important to supplement the risk-raising information with information that enhances personal efficacy to act and information about how those actions can result in positive impact.

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211 Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/074959789190020T

Anderson A (2011) Sources, media, and modes of climate change communication: the role of celebrities. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 2(4):535–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.119

Bandura A (1982) Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol 37(2):122–147 Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/amp/37/2/122/

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Beattie G, Sale L, Mcguire L (2011) An inconvenient truth? Can a film really affect psychological mood and our explicit attitudes towards climate change? Semiotica. Retrieved from http://www.degruyter.com/dg/viewarticle/j$002fsemi.2011.2011.issue-187$002fsemi.2011.066$002fsemi.2011.066.xml

Boykoff M, Roberts J (2007) Media coverage of climate change: current trends, strengths, weaknesses. Retrieved from http://rockyanderson.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/MediacoverageofCC-current-trends.pdf

Boykoff M, Goodman M, Littler J (2010) Charismatic megafauna’: the growing power of celebrities and pop culture in climate change campaigns. Environment, Politics and Development Working Paper Series Department of Geography, King’s College London, Paper 28. Retrieved from https://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/departments/geography/research/Research-Domains/Contested-Development/BoykoffetalWP28.pdf

Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, Pedersen OK (2013) Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol Methods Res 42(3):294–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124113500475

Carvalho, A., van Wessel, M., & Maeseele, P. (2017). Communication practices and political engagement with climate change: a research agenda. Taylor & Francis, 11(1), 122–135. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17524032.2016.1241815

Cook J, Oreskes N, Doran PT, Anderegg WRL, Verheggen B, Maibach EW et al (2016) Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environ Res Lett 11(4):048002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002

Cooper KE, Nisbet EC (2016) Green narratives: how affective responses to media messages influence risk perceptions and policy preferences about environmental hazards. Sci Commun 38(5):626–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547016666843

Doherty KL, Webler TN (2016) Social norms and efficacy beliefs drive the alarmed segment’s public-sphere climate actions. Nat Clim Chang 6(9):879–884. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3025

Doyle J, Farrell N, Goodman MK (2017) Celebrities and climate change, 1(October). https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.596

Feinberg M, Willer R (2011) Apocalypse soon? Dire messages reduce belief in global warming by contradicting just-world beliefs. Psychol Sci 22(1):34–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610391911

Feldman L, Hart PS (2016) Using political efficacy messages to increase climate activism: the mediating role of emotions. Sci Commun 38(1):99–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547015617941

Gerard J (2016) Leonardo DiCaprio’s ‘Before The Flood’ sampled by 30M+ worldwide for National Geographic. Retrieved from https://deadline.com/2016/11/before-the-flood-ratings-leonardo-dicaprio-national-geographic-1201847781/

Global Warming (2018) Retrieved August 20, 2008, from https://www.boxofficemojo.com/genres/chart/?id=globalwarming.htm

Green MC, Brock TC (2000) The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J Pers Soc Psychol 79(5):701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701

Green M, Brock T, Kaufman G (2004) Understanding media enjoyment: the role of transportation into narrative worlds. Commun Theory 14(4):311–327 Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00317.x/abstract

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006) How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18(1):59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

Howell RA (2011) Lights, camera ... action? Altered attitudes and behaviour in response to the climate change film The Age of Stupid. Glob Environ Chang 21(1) Retrieved from http://www.sociology.ed.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/180786/Howell_AoS_paper_1_pre-print.pdf

Howell RA (2014) Investigating the long-term impacts of climate change communications on individuals’ attitudes and behavior. Environ Behav 46(1):70–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512452428

Jacobsen GD (2011) The Al Gore effect: an inconvenient truth and voluntary carbon offsets. J Environ Econ Manag 61(1):67–78

Koletsou A, Mancy R (2011) Which efficacy constructs for large-scale social dilemma problems? Individual and collective forms of efficacy and outcome expectancies in the context of climate. Risk Management. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/rm.2011.12

Lakoff G (2010) Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environ Commun 4(1):70–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524030903529749

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Feinberg G, Rosenthal S (2013) Americans ’ actions to limit global warming in November 2013. New Haven, CT. Retrieved from http://environment.yale.edu/climate-communication-OFF/files/Behavior-November-2013.pdf

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renauf C (2014) Public support for climate and energy policies in November 2013. Yale project on climate change communication. New Haven, CT. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Public+Support+for+Climate+and+Energy+Policies+in+November+2013&btnG=&hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C47#0

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Feinberg G, Rosenthal S (2015) Climate change in the American mind: March, 2015. Yale project on climate change communication. Yale University and George Mason University, New Haven

Leiserowitz AA, Maibach EW, Roser-Renouf C, Rosenthal S, Cutler M (2017a) Climate change in the American mind: May 2017. New Haven, CT. Retrieved from http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/climate-change-american-mind-may-2017/

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Rosenthal S, Cutler M, Kotcher J (2017b) Climate change in the American mind October 2017, New Haven Retrieved from http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/climate-change-american-mind-october-2017/

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renauf C, Rosenthal S, Cutler M, Kotcher J (2018) Climate change in the American mind: March 2018, New Haven

Lorenzoni I, Nicholson-Cole S, Whitmarsh L (2007) Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob Environ Chang 17(3–4):445–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.01.004

Lubell M, Zahran S, Vedlitz A (2007) Collective action and citizen responses to global warming. Polit Behav Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11109-006-9025-2

Maibach E, Nisbet M, Baldwin P, Akerlof K, Diao G (2010) Reframing climate change as a public health issue: an exploratory study of public reactions. BMC Public 10(1):299 Retrieved from https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-10-299

Manzo K (2010) Beyond polar bears? Re-envisioning climate change. Meteorol Appl 17(2):196–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/met.193

Manzo K (2017) The usefulness of climate change films. Geoforum. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.006

Metag J, Schäfer MS, Füchslin T, Barsuhn T, Kleinen-von Königslöw K (2016) Perceptions of climate change imagery: evoked salience and self-efficacy in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Sci Commun. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547016635181

Meyer R (2015) How to make global warming look like a movie. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2015/09/making-climate-change-look-like-a-movie-years-of-living-dangerously-interview/406285/

Meyer R (2018) The global rightward shift on climate change. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/08/a-global-rightward-shift-on-climate-change/568684/

Moyer-Gusé E, Nabi RL (2010) Explaining the effects of narrative in an entertainment television program: overcoming resistance to persuasion. Hum Commun Res 36(1):26–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01367.x

Nabi RL, Green MC (2014) Emotional flow in promoting persuasive outcomes. Media Psychol 18(2):137–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2014.912585org/10.1080/15213269.2014.912585

Nabi RL, Gustafson A, Jensen R (2018) Framing climate change: exploring the role of emotion in generating advocacy behavior. Sci Commun. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547018776019

Nisbet M (2009) Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23

Nolan JM (2010) “An Inconvenient Truth” increases knowledge, concern, and willingness to reduce greenhouse gases. Environ Behav 42(5):643–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509357696

O’Neill S, Nicholson-Cole S (2009) “Fear Won’t Do It”: promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Sci Commun 30(3):355–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547008329201

O’Neill S, Boykoff M, Niemeyer S, Day SA (2013) On the use of imagery for climate change engagement. Glob Environ Chang 23(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.11.006

Ojala M (2012) Hope and climate change: the importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environ Educ Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.637157

Ojala M (2015) Hope in the face of climate change: associations with environmental engagement and student perceptions of teachers’ emotion communication style and future. J Environ Educ 46(3):133–148 Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00958964.2015.1021662

Rich N (2018) Losing Earth: the decade we almost stopped climate change. New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/08/01/magazine/climate-change-losing-earth.html

Roser-Renouf C (2014) Engaging diverse audiences with climate change: message strategies for global warming’s six Americas. Available at SSRN …. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2410650

Roser-Renouf C, Maibach EW, Leiserowitz A, Zhao X (2014) The genesis of climate change activism: from key beliefs to political action. Clim Chang 125(2):163–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1173-5

Schäfer M, Schlichting I (2014) Media representations of climate change: a meta-analysis of the research field. Environ Commun 8(2):142–160 Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17524032.2014.914050

Semenza J, Hall D, Wilson D, Bontempo B (2008) Public perception of climate change: voluntary mitigation and barriers to behavior change. Am J Prev Med 35(5):479–497 Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749379708006831

Slovic P, Peters E (2005) Affect, risk, and decision making. Health …. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2005-08085-006

Smith J, Firth J (2011) Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach. Nurse Res 18(2):52–62

Smith N, Leiserowitz A (2014) The role of emotion in global warming policy support and opposition. Risk Anal 34(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12140

Spence A, Pidgeon N (2010) Framing and communicating climate change: the effects of distance and outcome frame manipulations. Glob Environ Chang 20(4):656–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.002

Strecher V, DeVellis BM (1986) The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Education. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/109019818601300108

van der Linden S, Maibach E, Leiserowitz A (2015) Improving public engagement with climate change: five “Best Practice” insights from psychological science. Perspect Psychol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615598516

Vasi IB, Walker ET, Johnson JS, Tan HF (2015) “No Fracking Way!” documentary film, discursive opportunity, and local opposition against hydraulic fracturing in the United States, 2010 to 2013. Am Sociol Rev 80(5):934–959. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122415598534

Williams K, Bond M (2002) The roles of self-efficacy, outcome expectancies and social support in the self-care behaviours of diabetics. Psychology, Health & Medicine. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13548500120116076

Witte (1992) Putting the fear back into fear appeals: the extended parallel process model. Commun Monogr 59(4):329–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759209376276

Witte K (1994) Fear control and danger control: a test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM). Commun Monogr 61(2):113–134

Witte K, Allen M (2000) A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav 27(5):591–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810002700506

Years of Living Dangerously Season Two (2016) United States of America: National Geographic. Retrieved from http://yearsoflivingdangerously.com/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 20 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bieniek-Tobasco, A., McCormick, S., Rimal, R.N. et al. Communicating climate change through documentary film: imagery, emotion, and efficacy. Climatic Change 154, 1–18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02408-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02408-7