Abstract

Social protection can reduce HIV-risk behavior in general adolescent populations, but evidence among HIV-positive adolescents is limited. This study quantitatively tests whether social protection is associated with reduced unprotected sex among 1060 ART-eligible adolescents from 53 government facilities in South Africa. Potential social protection included nine ‘cash/cash-in-kind’ and ‘care’ provisions. Analyses tested interactive/additive effects using logistic regressions and marginal effects models, controlling for covariates. 18 % of all HIV-positive adolescents and 28 % of girls reported unprotected sex. Lower rates of unprotected sex were associated with access to school (OR 0.52 95 % CI 0.33–0.82 p = 0.005), parental supervision (OR 0.54 95 % CI 0.33–0.90 p = 0.019), and adolescent-sensitive clinic care (OR 0.43 95 % CI 0.25–0.73 p = 0.002). Gender moderated the effect of adolescent-sensitive clinic care. Combination social protection had additive effects amongst girls: without any provisions 49 % reported unprotected sex; with 1–2 provisions 13–38 %; and with all provisions 9 %. Combination social protection has the potential to promote safer sex among HIV-positive adolescents, particularly girls.

Resumen

La protección social puede reducir los comportamientos de riesgo asociados al VIH en los adolescentes en general, siendo los datos limitados en cuanto a adolescentes VIH-positivo se refiere. Este estudio se evalúa cuantitativamente si la protección social está asociada con la reducción de relaciones sexuales sin protección en una muestra de 1060 adolescentes elegibles para el tratamiento antirretroviral, en 53 instalaciones gubernamentales en Sudáfrica. En este estudio la protección social se midió usando nueve tipos de medidas de protección incluyendo efectivo, pago en especie y servicios de atención a la salud. Los efectos interactivos y aditivos de estas medidas se analizaron usando regresiones logísticas y modelos de efectos marginales, controlando por covariables. El 18 % de todos los adolescentes VIH positivo y el 28 % de las chicas adolescentes declararon haber tenido relaciones sexuales sin protección. Menores tasas de relaciones sexuales sin protección estuvieron asociadas con el acceso a la escuela (OR 0.52 95 % CI 0.33–0.82 p = 0.005), la supervisión parental (OR 0.54 95 % CI 0.33–0.90 p = 0.019), y la atención clínica adecuada a las necesidades de los adolescentes (OR 0.43 95 % CI 0.25–0.73 p = 0.002). El género moderó el efecto de la atención clínica adecuada a las necesidades de los adolescentes. La combinación de medidas de protección social tuvo efectos en las chicas adolescentes: sin ninguna medida de atención, el 49 % de las chicas declaro haber mantenido relaciones sexuales sin protección, mientras que con una o dos medidas el 13–38 %, y con todas las medidas solo el 9 %. La combinación de medidas de protección social tiene el potencial de promover relaciones sexuales seguras en los adolescentes VIH positivo, en particular en las chicas adolescentes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are an estimated 1.3–2.2 million HIV-positive adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa, both vertically and horizontally infected [1]. Studies have documented high rates of unprotected sex reported by HIV-positive adolescents even after HIV infection (27–90 %) [2–5]. While rates of unprotected sex among HIV-positive adolescents are comparable to those among the general adolescent population [2], HIV-positive adolescents are a key population for reducing onwards HIV transmission to sexual partners and children. In addition, HIV-positive adolescents experience a range of vulnerabilities that are likely to reduce the efficacy of HIV prevention programmes aimed at general populations, including cognitive and mental health issues [6, 7], family-related challenges [8, 9] and material deprivation [10, 11].

Adolescent girls and young women bear a disproportionate burden of the epidemic: three-quarters of all new HIV infections in Africa are among adolescent girls, and 80 % of all HIV-positive adolescent girls live in Sub-Saharan Africa [12, 13]. While notable research and resources are focused on supporting adolescent girls and young women to remain HIV-negative, there is a dearth of research and programming for HIV-positive girls. HIV-positive adolescent girls face multiple potential risks: low rates of condom and contraceptive use, greater rates of unwanted pregnancies and related health complications, as well as lower enrollment, adherence to, and retention in prevention-of-mother-to-child transmission programmes, and, consequently, increased risk of transmitting HIV to their partners and children [14–18].

Increasingly, social protection provisions are showing potential to reduce the negative impacts of structural deprivations faced by adolescents in high-prevalence contexts, and to improve their long-term health outcomes [19]. Although traditionally defined as a set of economic measures such as welfare payments or social cash transfers, recent conceptualisations of social protection recognise that it may take one of multiple forms [19–21]: ‘cash/cash-in-kind’ provisions to address economic barriers to food security, school access and health services, or psychosocial ‘care’ provisions such as support groups, supportive parenting or community services [22]. Most evidence to date has focused on impacts of social cash transfers in addressing structural vulnerabilities to HIV-infection among adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa [13]. But recent studies suggest that combinations of ‘cash/cash-in-kind’ and ‘care’ social protection provisions may have greater potential for reducing HIV risk-behaviour than single interventions [23, 24]. Two studies from South Africa and Kenya suggest that social protection may function differently for boys and girls [23, 25]. A longitudinal study of n = 2668 South African adolescents found that different combinations of ‘cash’ and ‘care’ social protection were associated with reductions in sexual risk-taking among adolescent girls compared to adolescent boys [23]. The evaluation of the Kenya cash transfer programme for orphans and vulnerable children showed overall reductions in sexual debut with greater impact among girls compared to boys [25]. A recent review in Eastern and Southern Africa reported an increasing evidence base on how social protection can reduce HIV infection among HIV-negative adolescents, but found no studies that investigate the role of social protection in preventing onwards HIV-transmission among HIV-positive adolescents [21]. There is a need for evidence on whether social protection provisions alone or in combination can reduce HIV-risk behavior for HIV-positive adolescents, and to understand potential gender differences.

To date, only a few programmes have tested any interventions to improve sexual and reproductive health among HIV-positive adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa. A small-scale randomised trial of a behavioural intervention among 14–21 year old HIV-positive youth in Uganda reported that intervention youth (n = 50) increased consistent condom use and reduced number of sexual partners significantly compared to controls (n = 50) [26]. Three studies suggest that ‘care’ interventions of support groups may be helpful in reducing risk behaviors amongst HIV-positive adolescents [27–29]. A pre-post test pilot study of structured support group sessions for HIV-positive adolescents (n = 65) in South Africa found improvements in self-reported condom use [27]. A qualitative study (n = 13) in the Democratic Republic of Congo, consisting of a 6-session group-based healthy living intervention reported better communication with sexual partners [29]. However, no large-scale or quantitative research has examined impacts of either ‘cash/cash-in-kind’ or ‘care’ social protection provisions, alone or in combination, on the sexual practices of HIV-positive adolescents. Combination social protection may have cumulative effects, that is beneficiaries of two or more provisions may do better than those receiving each provision alone. These effects may be multiplicative or additive [23].

This study aims to address this essential research gap. It uses the world’s largest community-traced sample of HIV-positive adolescents to investigate whether different types of social protection provisions: ‘cash/cash-in-kind’ or ‘care’, are associated with lower rates of unprotected sex. Based on a review of literature on social protection for HIV prevention [21], the following nine social protection provisions were tested: ‘cash/cash-in-kind’: social cash transfers, past-week food security, free school access (no fees and school materials), school feeding, and clothing, and psychosocial ‘care’ provisions: positive parenting, strong parental supervision, support groups, adolescent-sensitive care at clinics (respectful treatment by sexual health service providers). It tests (1) associations of each social protection provisions with unprotected sex, (2) the effects of gender on social protection provisions significantly associated with unprotected sex, (3) potential interactive effects of significant social protection provisions, and (4) potential additive effects of combination social protection provisions.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

1060 HIV-positive adolescents (10–19 year olds) were recruited from a health district in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. This was selected as a resource-limited setting with high HIV-prevalence rates [30]. The study was designed in collaboration with South African Departments of Health and Basic Education, UNICEF, PEPFAR-USAID, Pediatric AIDS Treatment for Africa (PATA) and local NGOs. Ethical approval for this study was provided by Research Ethics Committees at the Universities of Oxford (SSD/CUREC2/12-21) and Cape Town (CSSR 2013/4), Eastern Cape Departments of Health and Basic Education, and ethical review boards of participating hospitals.

The study aimed to include all 10–19 year old adolescents within the health district who were eligible to initiate ART. First, all healthcare facilities providing ART were visited (n = 83): all facilities who reported more than five ART-eligible adolescents were included in the study (n = 39). As the study progressed, the South African Department of Health implemented a primary healthcare reengineering programme, as a result of which the adolescents receiving care in the initial 39 facilities were transferred to a total of 53 healthcare facilities including hospitals, community healthcare centres, and primary healthcare clinics. All 53 facilities were then included in the study.

Adolescents were recruited at clinics where they were receiving antiretroviral treatment and care, or traced into their home communities for those not reachable at the clinics. All caregivers and adolescents participating in the study gave written informed consent prior to interviews, which took place in the language of their choice and lasted an average of 90 min. Of all study-eligible adolescents, n = 1060 (90.1 %) were interviewed, 4.1 % refused participation (either adolescent or caregiver), 0.9 % were excluded due to severe cognitive disability, 1.2 % were excluded due to living in very unsafe areas, and 3.7 % were untraceable. Participants who asked for help or disclosed abuse, neglect, defaulting from antiretroviral treatment or clinic care, severe hunger, or risk of significant harm were immediately assisted and linked to existing services (n = 66, 6.2 %). Due to high HIV-stigma rates, the study was presented in participating communities as a general study on adolescent access to health and social services. In order not to draw attention to HIV-affected families, when participants were traced and interviewed in communities, an additional n = 467 cohabitating or neighbouring age-peers were interviewed using a non HIV-specific version of the questionnaire (not included in this analysis).

Quantitative and qualitative research were combined iteratively during the study: qualitative research guided the design and content of the quantitative data collection tools and processes, preliminary quantitative analysis provided themes to be further explored by qualitative research, and these in-depth explorations shaped quantitative analyses. Quantitative questionnaires used standardised scales and validated measures when available. Tools were translated into Xhosa and back-translated for improved conceptual validity [31], then piloted with 25 HIV-positive adolescents from rural and urban sites in the health district. Questionnaires included graphics, interactive games and vignettes to introduce questions around sensitive topics. Interviews were administered by trained research assistants or via tablet-assisted self-interviewing, based on the participants’ literacy levels.

Measures

Unprotected sex at last sexual intercourse was measured as no condom use at most recent sexual encounter. It was dichotomised as: ‘1 = unprotected sex’ and ‘0 = abstinence or protected sex’. Adolescents were coded as STI symptomatic if they reported having at least one of the following four STI symptoms: genital sores/warts, burning whilst urinating, genital itching/redness, or anal itching/soreness/bleeding, in the last 6 months, following WHO guidelines for syndromatic diagnosis of STIs [32]. Adolescent pregnancy among girls was defined as ever having been pregnant before or during data collection, measured using an item from the National Survey of HIV and Risk Behaviour Amongst Young South Africans [33].

Socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, home language, housing situation, urban/rural location) were measured using items from South Africa’s Census [34]. Housing was coded as 1 = informal if the adolescent lived in a hut, rondavel (traditional home), or a shack, and 0 = formal if they lived in a brick/concrete house or apartment. Orphanhood status was coded as death of either mother or father or both [35].

HIV-Related Factors

Mode of infection was assessed following similar studies and modelling from Southern Africa [36, 37]: adolescents were coded as vertically-infected if they had started ART prior to age 12 or if they had been on treatment for more than 5 years, based on the year of widely available ART access in the study area. Adolescent’s knowledge of their own HIV-positive status was determined through a stepwise process: initially healthcare providers’ report, followed by confirmation by caregiver during the consent process. Additional checks on adolescent knowledge of own HIV-status were conducted using a screening on recent health and medication-taking histories to avoid unintentional disclosure. Adolescents who did not know their own HIV-positive status responded to a questionnaire on ‘illness’ and ‘medication’ instead of ‘HIV’ and ‘antiretrovirals’, respectively. Most recent viral loads were extracted from patient records for a random sub-sample (n = 266, 25 %). Participants with viral load counts >1000 copies/ml were coded as reporting virological failure using WHO standards [38].

Social Protection Provisions

‘Cash/cash-in-kind’ provisions of social protection included the following: Social cash transfers referred to participants’ household receiving at least one of South Africa’s five social welfare grants: child support grant, foster child grant, pension, disability or care dependency. Past-week food security, defined as at least two meals daily for the past week, was measured through items from the National Food Consumption Survey [39]. Access to school was defined as access to free schooling or ability to afford school fees, uniform and equipment. School feeding referred to receiving at least one free meal at school daily. Sufficient clothing was measured using an item from the South African Social Attitudes Survey [40]. Psychosocial ‘care’ provisions included: Positive parenting—including items on praise and positive reinforcement from caregiver—and good parental supervision—including monitoring of adolescent social activities and home rule-setting—measured using two sub-scales of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire [41]. Attending an HIV-support group was measured as past-month attendance at either a youth-focused or general HIV-support group. Adolescent-sensitive care at clinics was measured through two items asking adolescents about their experience obtaining contraception at the clinic: whether they felt disrespected or were scolded. These items were developed based on extensive qualitative research and consultations with HIV-positive adolescents in the study’s teen advisory group [15].

Data Analysis

Data analysis consisted of five steps: first, the included sample (90.1 %) was compared to the rest of the eligible sample across available key demographics (age, gender and residential location) to check for any differences. Descriptive statistics of socio-demographic characteristics, access to each social protection provision, and rates of unprotected sex were calculated for the full included sample and by gender. Covariates and social protection provisions were excluded from further analysis if sub-group sizes were too small for reliable analysis (cut-off n < 100 in the full sample, n < 50 per gender). To check the extent of risk for onwards HIV-transmission, we tested whether unprotected sex was associated with virological failure, a marker of high HIV-transmission risk through unprotected sex [42].

Second, validation checks for self-reported unprotected sex were conducted by testing associations between a) unprotected sex and STI symptomology (full sample) and b) unprotected sex and pregnancy (females only). These used multivariate logistic regression models controlling for all potential covariates.

Third, we tested potential associations of unprotected sex and seven social protection provisions: three ‘cash-in-kind’ and four ‘care’, using a multivariate logistic regression model, controlling for covariates. Covariates entered included: adolescent age, gender, language, housing type, residential location, maternal and paternal orphanhood, living with biological caregiver, mode of infection, and knowledge of own HIV-positive status.

Fourth, we tested whether gender acted as a moderator for each social protection provision. Moderator analyses were conducted using logistic regression models with two-way interaction terms of gender and each social protection provisions entered in separate models, controlling for covariates found significant in the above step. Subsequently, based on existing literature suggesting different social protection provisions may work for adolescent boys and girls, and because a moderator effect was found, multivariate logistic regressions were run separately for HIV-positive girls and boys.

Fifth, effects of combinations of social protection provisions on unprotected sex were tested for the full and then gender-disaggregated samples. To check for potential interaction effects, all significant social protection variables, covariates and interaction terms from stage 3 above (p < .05) were added in a stepwise multivariate logistic regression model, following processes applied by similar studies [23]. Step 1—all covariates significant from the model in stage 3, step 2—all significant social protection variables, step 3—all two-way interaction terms of significant social protection variables, step 4—all three-way and higher order interaction terms of significant social protection variables. Subsequently, marginal effect analysis in STATA tested potential additive effects of significant social protection provisions by computing predicted probabilities of unprotected sex under each potential combination of significant social protection provisions, with all significant covariates held at mean values.

Results

Socio-Demographic and HIV-Related Factors (Table 1)

Over half the sample was female (55 %) with average age 13.8 (SD = 2.8). 19 % lived in informal housing. 22 % lived in rural areas. Almost all participants spoke Xhosa at home (97 %) and just under half lived with a biological caregiver (45 %). 44 % were maternal orphans, 30 % paternal orphans, and 15.4 % had lost both parents. 67 % were vertically-infected and 75 % knew their own HIV-positive status. Due to small sub-sample sizes of non-Xhosa speakers (<50 for each gender), home language was excluded from further analyses. There were no significant differences between the included (n = 1060) and excluded eligible participants (n = 116), when compared across age, gender and residential location.

Sexual Outcomes: (Table 2)

18 % of HIV-positive adolescents reported having unprotected sex at last intercourse, with girls reporting significantly higher rates than boys (28 % vs. 4 %, OR 8.46, 95 % CI 5.27–13.58 p ≤ .001). 32 % of HIV-positive girls were STI symptomatic compared to 27 % of boys (OR 1.23 95 % CI 0.99–1.69 p = 0.059), with 13 % of all HIV-positive girls reporting past or current pregnancy.

Transmission Risk

Unprotected sex was strongly associated with virological failure in the sub-sample for whom viral load data was available (n = 266, OR 2.57 95 % CI 1.01–6.53 p = 0.048), suggesting that a sub-group of HIV-positive adolescents who are not virally suppressed and engage in unprotected sex are at high risk for HIV-transmission to uninfected sexual partners and children. Gender-disaggregated analyses were not possible due to small sub-sample sizes.

Access to Social Protection Provisions (Table 2)

‘Cash/cash-in-kind’: 95 % of adolescents reported that their household received at least one cash grant and 77 % had enough food to eat in the past week. 66 % had no economic barriers to access school, 93 % received regular school feeding, and 67 % had enough clothes to stay warm and dry. ‘Care’: 13 % attended any HIV support group, 41 % reported high parental supervision and 50 % reported high positive parenting. HIV-positive adolescent boys reported higher rates of food security (Χ 2 (df) = 9.395 [1], p = 0.002), greater access to school (Χ 2 (df) = 15.393 [1], p ≤ 0.001), and more adolescent-sensitive SRH care at clinics (Χ 2 (df) = 16.610 [1], p ≤ 0.001) than girls. Due to the very small groups of adolescents not receiving social cash transfers and school feeding schemes (<100 in the full sample, <50 by gender), these provisions were excluded from further analyses.

Validating Self-Reported Unprotected Sex (Table 3)

In multivariate logistic regression, self-reported unprotected sex was strongly associated with STI symptomology in the full sample (OR 1.54 95 % CI 1.00–2.38 p = 0.05) and with adolescent pregnancy among girls only (OR 5.72 95 % CI 2.51–13.03 p ≤ 0.001).

Associations of Individual Social Protection Provisions with Unprotected Sex (Table 4)

Table 4 shows the results of the multivariate regression model of the included social protection provisions. In the full sample, ‘cash-in-kind’ provision of school access (OR 0.52 95 % CI 0.33–0.82 p = 0.005), ‘care’ good parental supervision (OR 0.54 95 % CI 0.33–0.90 p = 0.019), and adolescent-sensitive ‘care’ at the clinic (OR 0.43 95 % CI 0.25–0.73 p = 0.002) were associated with less unprotected sex.

Gender Effects (Tables 5, 6)

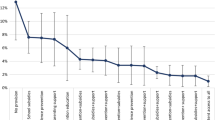

Of all social protection provisions only the interaction between gender and adolescent-sensitive clinic care was significant (OR 0.08 95 % CI 0.01–0.69 p = 0.021), suggesting that the effect of adolescent-sensitive clinic care on reducing unprotected sex was significantly greater among HIV-positive adolescent girls than boys (Fig. 1): adjusted probabilities of reporting unprotected sex among HIV-positive girls who accessed adolescent-sensitive clinic services was 14 % compared to 28 % among those who did not. The effect of accessing adolescent-sensitive clinic services was weaker among HIV-positive adolescent boys: with access to services 3 % were likely to report unprotected sex compared to 6 % among those who did not report adolescent-sensitive clinic services.

In subsequent gender-disaggregated regression analyses (Table 6), lower odds of unprotected sex among HIV-positive girls were significantly associated with three social protection provisions: school access (OR 0.49 95 % CI 0.29–0.82 p = 0.007), good parental supervision (OR 0.54 95 % CI 0.30–0.98 p = 0.043) and adolescent-sensitive clinic care (OR 0.32 95 % CI 0.17–0.58 p ≤ 0.001). No social protection provisions were associated with unprotected sex amongst HIV-positive boys.

Potential Interactive and Additive Effects (Tables 7, 8)

No significant interactive/multiplicative effects of social protection provisions were found in the full sample or for adolescent girls.

However, the independently significant effects of social protection provisions in Table 4 suggested potential additive effects. Strong additive effects were shown in the full sample and among HIV-positive adolescent girls. Among all HIV-positive adolescents, who had no access to school, good parental supervision, nor adolescent-sensitive clinic care, 22 % reported unprotected sex at last intercourse. Those receiving one social protection 11–15 % reported unprotected sex, and with any two: 6–8 % probability of unprotected sex. Adolescents receiving all three social protection provisions were likely to report just under 4 % unprotected sex. Amongst HIV-positive girls, rates of unprotected sex dropped from 49 % with no social protection provisions, to 23–38 % with one, 13–24 % with two and just under 9 % with all three social protection provisions (Fig. 2). As no social protection provisions were significantly associated with unprotected sex among HIV-positive boys, marginal effects models were not conducted.

Discussion

Findings from this study have several important implications. First, we found high rates of unprotected sex reported by HIV-positive adolescents, and significantly higher rates of virological failure amongst HIV-positive adolescents engaging in unprotected sex, suggesting greater transmission risk to uninfected peers. It is clear that effective programming to reduce sexual risk behavior for this vulnerable group is essential.

Second, we identify three types of social protection provisions that are strongly associated with reduced unprotected sex among HIV-positive adolescents: access to schools, good parental supervision, and adolescent-sensitive sexual health care at clinics. These findings reflect emerging evidence on combinations of social protection for reducing sexual risk-taking among general samples of adolescents [23]. They support recent calls for adolescent-sensitive HIV-inclusive social protection, that is social protection that reaches HIV-positive and HIV-affected adolescents without using HIV status as a targeting condition [21]. This study’s results show that HIV-inclusive social protection has the potential to reduce HIV risk-taking without the associated stigma of HIV-specific interventions.

Third, we extend this existing research by showing that combining two types of social protection: ‘cash-in-kind’ (school access) and ‘care’ (good parental supervision and adolescent-sensitive sexual health clinic care) has the greatest potential to reduce unprotected sex the most. Compared to those receiving none or one social protection provision, adolescents who receive two types of social protection reported lower rates of unprotected sex, with those receiving three types of social protection reporting the lowest rates. These findings suggest that ‘care’ social protection may act as the ‘glue’ for cash social protection to have positive effects, or vice versa. Additional research is needed to elucidate these potential mechanisms.

Fourth, our findings highlight the importance of receiving social protection in three key locations for adolescents: school, home and clinic. These findings confirm evidence from the region on adolescents more generally, with access to school serving as a ‘social vaccine’, bolstering social pathways associated with improved resilience [13]. Additionally, receiving adolescent-sensitive ‘care’ services from sexual healthcare providers at clinics was also associated with lower rates of unprotected sex. This finding supports qualitative reports from South Africa on the negative effect of poor clinic care on adolescent sexual and reproductive health outcomes [43]. Further analyses, including in-depth qualitative research, are needed to better understand the mechanisms through which classroom- and clinic-level support is linked to reduced unprotected sex.

Fifth, our gender-disaggregated analyses resulted in different significant social protection for boys and girls, though this may also be due to reduced power and the lower rates of sexual activity reported by the HIV-positive adolescent boys in our sample [15]. Three of the social protection provisions we tested have significant effects on HIV-positive adolescent girls: access to schools, good parental supervision, and adolescent-sensitive sexual health clinic care. Supporting adolescent girls beyond the home setting, at school and clinics, will not only ensure they reach services critical to their long-term well-being, but also support them in engaging in safer sex. Notably, these three provisions are—when available—targeted at all adolescents, whether HIV-positive or not. This suggests that social protection that reaches at-risk populations such as adolescents, even when not targeted to HIV-positive ones, can be effective to reduce their vulnerabilities. These findings resonate with advocacy for generalised social protection in the Sustainable Development Goals [13]. They also underline the importance of ensuring that HIV-positive adolescents are not excluded from accessing social protection.

This study has several methodological limitations. Cross-sectional analyses always limit our ability to reach conclusions on the direction of the observed associations, due to potential reverse causality for significant associations. Future research can valuably test these associations in longitudinal quasi-experimental studies or randomised controlled trials. Second, self-reported sexual health outcomes contain risk of social desirability bias. As a check for validity, we tested associations of self-reported unprotected sex with two other sexual and reproductive health outcomes. Unprotected sex was significantly associated with pregnancy and STI symptomology. Third, although over 90 % of all eligible adolescents in the health district were included in this sample, it is possible that adolescents at highest risk were those who refused or were untraceable. However, comparison of the sample reached and those not reached showed no significant differences by age, gender and residential location—the only information available to us. Despite this limitation, our study is the first and largest study of HIV-positive adolescents traced into their homes and communities, and thus may allow more representativity of the overall population than clinic-based samples that are thus restricted to those who attend healthcare services. Moreover, by including study sites with high HIV prevalence and relatively poor resources, our findings may be applicable to contexts with similar socio-economic and epidemiological profiles.

Participants in our sample reported very high coverage of certain social protection provisions: social cash transfers and school feeding (>90 %). These coverage rates not only limited our ability to conduct sub-group analyses but also precluded us from reaching any conclusions on whether they may be associated with sexual health outcomes among HIV-positive adolescents. However, given prior evidence from South Africa on the effectiveness of social cash transfers in reducing sexual risk-taking among AIDS-affected adolescents [24, 44], our findings suggest that the positive effect of additional social protection may extend gains from the social cash transfer and school feeding schemes documented by prior studies in the region.

Despite the above limitations, the study provides key insights for sexual health programming among HIV-positive adolescents in and out of clinical care. The interventions identified are available in real-life settings and have statistically and practically significant associations with reduced unprotected sex, particularly when accessed in combination. Increasing access to these social protection provisions among HIV-positive adolescents has the potential to support HIV-positive adolescents to reduce unprotected sex, and its related outcomes of unwanted pregnancies and onwards HIV-transmission.

References

UNICEF. Towards an AIDS-free generation—children and AIDS: sixth stocktaking report. New York; 2013.

Mergui A, Giami A. The sexuality of HIV-infected adolescents: literature review and thinking the unthinkable of sexuality. Arch Pediatr. 2011;18:797–805.

Cataldo F, Malunga A, Rusakaniko S, Umar E, Teles N, Musandu H. Experiences and challenges in sexual and reproductive health for adolescents living with HIV in Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe. In: XIX international AIDS conference. Washington D.C.; 2012. p. MOAD0104.

Birungi H, Obare F, Mugisha JF, Evelia H, Nyombi J. Preventive service needs of young people perinatally infected with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2009;21(6):725–31.

Beyeza-Kashesya J, Kaharuza F, Ekstrom AM, Neema S, Kulane A, Mirembe F, et al. To use or not to use a condom: a prospective cohort study comparing contraceptive practices among HIV-infected and HIV-negative youth in Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(144):1–11.

Lowenthal ED, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Marukutira T, Chapman J, Goldrath K, Ferrand RA. Perinatally acquired HIV infection in adolescents from Sub-Saharan Africa: a review of emerging challenges. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:627–39.

Sherr L, Croome N, Parra Castaneda K, Bradshaw K, Herrero Romero R. Developmental challenges in HIV infected children—an updated systematic review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;45:74–89.

Amzel A, Toska E, Lovich R, Widyono M, Patel T, Foti C, et al. Promoting a combination approach to paediatric HIV psychosocial support. AIDS [internet]. 2013;27 Suppl 2:S147–57. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24361624.

Wiener LS, Battles HB. Untangling the web: a close look at diagnosis disclosure among HIV-infected adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:307–9.

Mellins CA, Bhana A, Petersen I, Holst H, Alicea S, Myeza N, et al. The VUKA family project: a family-based mental health and HIV prevention program for perinatally HIV-positive youth. In: XIX international AIDS conference. Washington D.C.; 2012.

Busza J, Besana GVR, Mapunda P, Oliveras E. I have grown up controlling myself a lot. Fear and misconceptions about sex among adolescents vertically-infected with HIV in Tanzania. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21(41):87–96.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), African Union (AU). Empower young women and adolescents girls: fast-tracking the end of the AIDS epidemic in Africa [internet]. Geneva; 2015. p. 32. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2746_en.pdf.

UNICEF-ESARO TP. Social cash transfers and children’s outcomes: a review of evidence from Africa [internet]. 2015. https://transfer.cpc.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Social-Cash-Transfer-Publication-ESARO-December-2015.pdf.

Fatti G, Shaikh N, Eley B, Jackson DJ, Grimwood A. Adolescent and young pregnant women at increased risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and poorer maternal and infant health outcomes: a cohort study at public facilities in the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan district, Eastern cape, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2014;104:874–80.

Toska E, Cluver LD, Hodes RJ, Kidia KK. Sex and secrecy: how HIV-status disclosure affects safe sex among HIV-positive adolescents. AIDS Care. 2015;27(sup1):47–58.

Cluver LD, Hodes RJ, Toska E, Kidia KK, Orkin FM, Sherr L, et al. HIV is like a tsotsi. ARVs are your guns”: associations between HIV-disclosure and adherence to antiretroviral treatment among adolescents in South Africa. AIDS. 2015;29:S57–65.

Test FS, Mehta SD, Handler A, Mutimura E, Bamukunde AM, Cohen M. Gender inequities in sexual risks among youth with HIV in Kigali, Rwanda. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(6):394–9.

Obare F, Van Der Kwaak A, Birungi H. Factors associated with unintended pregnancy, poor birth outcomes and post-partum contraceptive use among HIV-positive female adolescents in Kenya. BMC Womens Health. 2012;12(34):1–8.

Cluver LD, Hodes RJ, Sherr L, Orkin FM, Meinck F, Lim PLAK, et al. Social protection: potential for improving HIV outcomes among adolescents. J Int AIDS Soc [internet]. 2015;18(Suppl 6):202–607. http://www.jiasociety.org/index.php/jias/article/view/20260.

Devereux S, Sabates-Wheeler R. Editorial introduction: debating social protection. IDS Bull. 2007;38(3):1–7.

Toska E, Gittings L, Cluver LD, Hodes RJ, Chademana E, Gutierrez VE. Resourcing resilience: social protection for HIV prevention amongst children and adolescents in Eastern and Southern Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2016;15(2):123–40.

The African Child Policy Forum (ACPF). Social protection that benefits children: a moral imperative and viable strategy for growth and development. Addis Ababa: The African Child Policy Forum (ACPF); 2014.

Cluver LD, Orkin FM, Yakubovich AR, Sherr L. Combination social protection for reducing HIV-risk behavior amongst adolescents in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(1):96–104.

Cluver LD, Orkin FM, Boyes ME, Sherr L. Cash plus care: social protection cumulatively mitigates HIV-risk behaviour among adolescents in South Africa. AIDS. 2014;28(Suppl 3):S389–97.

Handa S, Halpern CT, Pettifor AE, Thirumurthy H. The government of Kenya’s cash transfer program reduces the risk of sexual debut among young people age 15–25. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85473.

Lightfoot MA, Kasirye R, Comulada WS, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Efficacy of a culturally adapted intervention for youth living with HIV in Uganda. Prev Sci. 2007;8:271–3.

Snyder K, Wallace M, Duby Z, Aquino LDH, Stafford S, Hosek S, et al. Preliminary results from Hlanganani (coming together): a structured support group for HIV-infected adolescents piloted in Cape Town, South Africa. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;45:114–21.

Senyonyi RM, Underwood LA, Suarez E, Musisi S, Grande TL. Cognitive behavioral therapy group intervention for HIV transmission risk behavior in perinatally infected adolescents. Health. 2012;4(12):1334–45.

Parker L, Maman S, Pettifor AE, Chalachala JL, Edmonds A, Golin CE, et al. Adaptation of a U.S. evidence-based positive prevention intervention for youth living with HIV/AIDS in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Eval Program Plan. 2013;36:124–35.

Department of Health. The 2011 national antenatal sentinel HIV and syphilis prevalence survey in South Africa. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2012.

Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1(3):185–216.

World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted infections [internet]. World Health Organization; 2004. p. 88. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2942e/.

Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Steffenson A, Madikizela-Hlongwa L, Macphail C, Kleinschmidt I. HIV and sexual behaviour among young South Africans: a national survey of 15–24 year olds. Johannesburg: University of Witswatersrand; 2004.

Statistics South Africa (SSA). Census 2011 methodoloy and highlights of key results. 2011.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), (UNICEF) TUNCF, (USAID) TUSA for ID. Children on the brink 2004 [internet]. New York; 2004. http://www.unicef.org/publications/cob_layout6-013.pdf.

Evans D, Menezes C, Mahomed K, Macdonald P, Untiedt S, Levin L, et al. Treatment outcomes of HIV-infected adolescents attending public-sector HIV clinics across Gauteng and Mpumalanga, South Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2013;29(6):892–900.

Ferrand RA, Corbett EL, Wood R, Hargrove J, Ndhlovu CE, Cowan FM, et al. AIDS among older children and adolescents in Southern Africa: projecting the time course and magnitude of the epidemic. AIDS. 2009;23(15):2039–46.

World Health Organization (WHO). Technical and operational considerations for implementing HIV viral load testing: interim technical update [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. p. 28. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128121/1/9789241507578_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1.

Labadarios D, Steyn NP, Maunder EMW, MacIntryre U, Gericke G, Swart R, et al. The national food consumption survey (NFCS): South Africa, 1999. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(5):533–43.

Pillay U, Roberts B, Rule SP. South African social attitudes: changing times, diverse voices. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2006. p. 391.

Elgar FJ, Waschbusch DA, Dadds MR, Sigvaldason N. Development and validation of a short form of the Alabama parenting questionnaire. J Child Fam Stud. 2007;16(2):243–59.

Eshleman SH, Hudelson SE, Ou SS, Redd AD, Swanstrom R, Porcella SF, et al. Treatment as prevention: characterization of partner infections in the HIV prevention trials network 052 trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(Supplement 4):18.

Wood K, Jewkes RK. Blood blockages and scolding nurses: barriers to adolescent contraceptive use in South Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(27):109–18.

Cluver LD, Boyes ME, Orkin MF, Pantelic M, Molwena T, Sherr L. Child-focused state cash transfers and adolescent risk of HIV infection in South Africa: a propensity-score-matched case-control study. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e362–70.

Acknowledgments

This study would not be possible without the experiences shared by over 1500 adolescents, their caregivers and healthcare providers, to whom we are immensely grateful. A joint University of Oxford-University of Cape Town team collaborated with UNICEF, the South African National Departments of Health, Basic Education and Social Development and Paediatric AIDS Treatment for Africa, and local CBOs: the Keiskamma Trust, the Raphael Centre, and Small Projects Foundation to design and conceptualize the study. Research was conducted by a dedicated research team, including: Julia Rosenfeld, Maya Isaacsohn, Marija Pantelic, Louis Pilard, Izidora Skracic, Nontuthuzelo Bungane, Janina Steinert, Rocio Herrero Romero, Craig Carty, Gerry Boon, Luntu Galo, Cheree Goldswain, Justus Hofmeyr, Sibongile Mandondo and Lulama Sidloyi. Rajen Govender, Nicoli Nattrass and Mpumi Zungu provided advice and mentorship. The study was conducted in collaboration with the Pediatric AIDS Management Programme of the Eastern Cape provincial Department of Health, and by 53 health facilities in the Buffalo City sub-district and Amathole district, Eastern Cape, South Africa.

Funding

The study was supported by the Nuffield Foundation under Grant CPF/41513, the International AIDS Society through the CIPHER grant (155-Hod), the Clarendon-Green Templeton College Scholarship (ET), the Janssen Global Health Educational Grant Programme, and the Evidence for HIV Prevention in Southern Africa, a DFID programme managed by Mott MacDonald (MM/EHPSA/UCT/05150014). Analyses and writing were supported by UNICEF—we thank Anurita Bains, Tom Fenn and Patricia Lim Ah Ken for input and discussion. Additional support for LC was provided by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC grant agreement n°313421 and the Philip Leverhulme Trust (PLP-2014-095).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Elona Toska declares that they have no conflict of interest. Lucie Cluver declares that they have no conflict of interest. Mark Boyes declares that they have no conflict of interest. Maya Isaacsohn declares that they have no conflict of interest. Rebecca Hodes declares that they have no conflict of interest. Lorraine Sherr declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Research Involving Human Participants

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Selected classifications

1.002: Condom use; 1.003: Community interventions; 1.009: Prevention policy; 4.001: Adolescents; 5.010: Southern Africa; 1.010: Risk behavior measurement; 1.011: Risk correlates and predictors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Toska, E., Cluver, L.D., Boyes, M.E. et al. School, Supervision and Adolescent-Sensitive Clinic Care: Combination Social Protection and Reduced Unprotected Sex Among HIV-Positive Adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Behav 21, 2746–2759 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1539-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1539-y