Abstract

This paper investigates whether engaging in regular exercise leads to higher earnings in the labor market. While there has been a recent surge of interest by economists on the issue of obesity, relatively little attention has been given to the economic effects of regular physical activity apart from its impact on body composition. I find that engaging in regular exercise yields a 6 to 10% wage increase. The results also show that while even moderate exercise yields a positive earnings effect, frequent exercise generates an even larger impact. These findings are fairly robust to a variety of estimation techniques, including propensity score matching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While the life-cycle hypothesis predicts that individuals will substitute towards leisure when wages are low (as they are during an economic downturn) it is important to bear in mind that hours worked is not a decision taken unilaterally by the worker. A significant portion of the decline in average work hours during an economic downturn is likely dictated by employers.

While hours of work may be fairly unresponsive to wage changes, individuals may respond to wage increases by decreasing the amount of time they spend on household work (by eating out more often or hiring a cleaning service) and spending more time on leisure activities or exercising. If exercise services are a normal good, then the income effect of a wage or salary increase may lead to greater consumption of these services.

The sample examined in this paper contains a maximum of two observations per individual.

Thus, I can no longer employ the categorical exercise variable. Instead, the primary PSM estimation focuses on the effects of frequent exercise.

Robustness checks address the issue of reverse causality. These tests are described later in the paper.

Only 17% of individuals who did not participate in athletics in high school report frequent exercise in the current sample compared to 27% for those who did participate in high school athletics. The percentages for exercising at least once per week are 32.7 and 47.4 for non-high school athletes and high school athletes, respectively.

Ruhm defines regular exercise as exercising three or more times a week for at least 20 min. The NLSY79 did not collect information on the duration or intensity of exercise, only the frequency.

The coefficient on black is no longer statistically significant.

Estimates using kernel and nearest neighbor matching are presented in appendix table 9 as a robustness check. The results are qualitatively similar with those obtained using the stratification matching method. In most cases, the estimates obtained using the other matching methods are even larger than the ones presented in table five.

Fitting the model using each category of exclusions separately did not yield substantially reduced coefficients on the overweight and obese variables for the part-time and extreme BMI restrictions. The large drop in the estimated coefficients occurs when low-wage workers are excluded from the sample.

In order to meet the balancing criterion, the occupation and year indicators were dropped from the first stage of the estimation routine for both samples. Neither the occupation nor the year indicators exhibited a significant correlation with the exercise variable in the first stage indicating that it is safe to exclude them.

References

Auld MC (2005) Smoking, drinking, and income. J Hum Resour 40(2):505–518

Averett S, Korenman S (1996) The economic reality of the beauty myth. J Hum Resour 31:304–330

Balsa AI, French MT (2009) Alcohol use and the labor market in Uruguay. Health Econ 19:833–854

Barron JM, Ewing BT, Waddell GR (2000) The effects of high school athletics participation on education and labor market outcomes. Rev Econ Stat 82:409–421

Baum CL, Ford WF (2004) The wage effects of obesity: a longitudinal study. Health Econ 13:885–899

Berry LL, Mirabito AM, Baun WB (2010) What’s the hard return on employee wellness programs? Harv Bus Rev. December: 104–112

Bhattacharya J, Bundorf MK (2009) The incidence of healthcare costs of obesity. J Health Econ 28:649–658

Biddle JE, Hamermesh DS (1998) Beauty, productivity, and discrimination: lawyer’s looks and lucre. J Labor Econ 16(1):172–201

Case A, Paxson C (2008) Stature and status: height, ability, and labor market outcomes. J Polit Econ 116:499–532

Cawley J (2004) The impact of obesity on wages. J Hum Resour 39(2):451–474

Chou S-Y, Grossman M, Saffer H (2004) An economic analysis of adult obesity: results from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Health Econ 23:565–587

Chung M, Melnyk P, Blue D, Renaud D, Breton M-C (2009) Worksite Health Promotion: the value of the tune up your heart program. Popul Health Manag 12(6):297–304

Cipriani GP, Zago A (2011) Productivity or discrimination? Beauty and the exams. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 73(3):428–447

Clegg CW (1983) Psychology of employee lateness, absence, and turnover: a methodological critique and an empirical study. J Appl Psychol 68(1):88–101

Eide ER, Ronan N (2001) Is participation in high school athletics an investment or a consumption good? Econ Educ Rev 20:431–442

Etnier JL, Salazar W, Landers DM, Petruzzello SJ, Han M, Nowell P (1997) The influence of physical fitness and exercise upon cognitive functioning: a meta-analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol 19:249–277

Ettner SL (1996) New evidence on the relationship between income and health. J Health Econ 15:67–85

French E (2004) The labor supply response to (mismeasured but) predictable wage changes. Rev Econ Stat 86(2):602–613

Folkins CH, Sime WE (1981) Physical fitness training and mental health. Am Psychol 36(4):373–389

Gregory CA, Ruhm CJ (2011) Where does the wage penalty bite? In: Grossman M, Mocan N (eds) Economic aspects of obesity. University of Chicago Press, pp 315–347

Hamilton V, Hamilton BH (1997) Alcohol and earnings: does drinking yield a wage premium? Can J Econ 30(1):135–151

Hamermesh DS, Biddle JE (1994) Beauty and the labor market. Am Econ Rev 84(5):1174–1194

Hamermesh DS, Meng X, Zhang J (2002) Dress for success- does primping pay? Lab Econ 9:361–373

Han E, Norton EC, Powell LM (2009a) Direct and indirect effects of teenage body weight on adult wages. NBER working paper #15207

Han E, Norton EC, Stearns SC (2009b) Weight and wages: fat versus lean paychecks. Health Econ 18:535–548

Harper B (2000) Beauty, stature and the labour market: a British cohort study. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 62:771–800

Heckman JJ, Ishimura H, Todd PE (1997) Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator. Rev Econ Stat 65(2):261–294

Hillman CH, Erickson KI, Kramer AF (2008) Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 9(1):58–65

Johnston DW (2010) Physical appearance and wages: do blondes have more fun? Econ Lett 108:10–12

Jones AS, Richmond DW (2006) Causal effects of alcoholism on earnings: estimates from the NLSY. Health Econ 15:849–871

Lakdawalla D, Philipson T (2009) The growth of obesity and technological change. Econ Hum Biol 7:283–293

Lechner M (2009) Long-run labour market and health effects of individual sports activities. J Health Econ 28:839–854

MacDonald Z, Shields MA (2001) The impact of alcohol consumption on occupational attainment in England. Economica 68:427–453

Mangione TW, Quinn RP (1975) Job satisfaction, counterproductive behavior and drug use at work. J Appl Psychol 60:114–116

Miller AR (2011) The effects of motherhood timing on career path. J Popul Econ 24:1071–1100

Mobius MM, Rosenblat TS (2006) Why beauty matters. Am Econ Rev 96(1):222–235

Mocan N, Tekin E (2010) Ugly criminals. Rev Econ Stat 92(1):15–30

Mocan N, Tekin E (2011) Obesity, self-esteem and wages. In: Grossman M, Mocan N (eds) Economic aspects of obesity. University of Chicago Press, pp 349–380

Morris S (2006) Body mass index and occupational attainment. J Health Econ 25:347–364

Persico N, Postlewaite A, Silverman D (2004) The effect of adolescent experience on labor market outcomes: the case of height. J Polit Econ 112:1019–1053

Prentice AM, Jebb SA (2001) Beyond body mass index. Obes Rev 2:141–147

Puetz TW (2006) Physical activity and feelings of energy and fatigue. Sports Med 36(9):767–780

Renna F (2008) Alcohol abuse, alcoholism, and labor market outcomes: looking for the missing link. Ind Labor Relat Rev 62(1):92–103

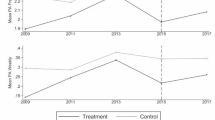

Ruhm CJ (2000) Are recessions good for your health? Q J Econ 115:616–650

Ruhm CJ (2005) Healthy living in hard times. J Health Econ 24:341–363

Smith JA, Todd PE (2005) Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of nonexperimental estimators? J Econometrics 125(1–2):305–353

Spence JC, McGannon KR, Poon P (2005) The effect of exercise on global self-esteem: a quantitative review. J Sport Exerc Psychol 27:33–334

Stevenson B (2010) Beyond the classroom: using Title IX to measure the return to high school sports. Rev Econ Stat 92(2):284–301

Thogerson-Ntoumani C, Fox KR, Ntoumanis N (2005) Relationships between exercise and three components of mental well-being in corporate employees. Psychol Sport Exerc 6:609–627

Tomporowski PD (2003) Effects of acute bouts of exercise on cognition. Acta Psychol 112:296–324

van Ours JC (2004) A pint a day raises a man’s pay; but smoking blows that gain away. J Health Econ 23:863–886

Ziebarth NR, Grabka MM (2009) In vino pecunia? The association between beverage-specific drinking behavior and wages. J Labor Res 30:219–244

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kosteas, V.D. The Effect of Exercise on Earnings: Evidence from the NLSY. J Labor Res 33, 225–250 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-011-9129-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-011-9129-2