Abstract

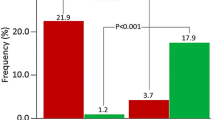

Angiographic follow-up studies on the evolution of coronary artery disease are of increasing relevance. It has still to be evaluated which coronary segments are predominantly involved in the process of atherosclerosis and, thus, should be preferably included in the analysis. Therefore, the correlation of progression and regression of coronary disease with the diameter and location (proximal, mid or distal) of coronary segments was investigated from the data of the INTACT-study, in which 25 different coronary segments were defined including anatomic variants of rather distal segments. In 348 patients with coronary artery disease, standardized coronary angiograms were repeated within 3 years and were quantitatively analyzed (CAAS). In 1063 coronary stenoses (% diameter stenosis > 20%) compared from both angiograms, progression and regression were not influenced by diameter nor location of arterial segments. In the follow-up angiograms, the number of new lesions (stenoses and occlusions) per coronary segment differed with regard to segment diameter (> 3 mm: 64/1125 (6%); 2–3 mm: 139/1967 (7%);<2 mm: 44/1756 (2%); p<0.001) and location of segments (proximal: 86/1285 (7%); mid: 84/1193 (7%); distal: 77/2370 (3%); p<0.001). Out of 77 distal new lesions, only 25 (32%) were found in segments<2 mm in diameter.

Since the absolute number of new lesions was high in distal coronary segments, but low in segments with diameters<2 mm, angiographic follow-up studies should analyze coronary segments at any location, but may neglect segments with diameters smaller than 2 mm.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gensini GG, Kelly AE. Incidence and progression of coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med 1972; 129: 814–27.

Rösch J, Antonovic R, Trenouth RS, Rahimtoola SH, Sim DN, Dotter CT. The natural history of coronary artery stenosis. Radiology 1976; 19: 513–20.

Marchandise B, Bourassa MG, Chaitman BR, Lespérance J. Angiographic evaluation of the natural history of normal coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol 1978; 41: 216–20.

Bruschke AVG, Wijers TS, Kolsters W, Landmann J. The anatomic evolution of coronary artery disease demonstrated by coronary arteriography in 256 nonoperated patients. Circulation 1981; 63: 527–36.

Palac RT, Hwang MH, Meadows WR, Croke RP, Pifarre R, Loeb HS, Gunnar RM. Progression of coronary artery disease in medically and surgically treated patients 5 years after randomization. Circulation 1981; 64 (suppl II): II17-II21.

Nash DT, Gensini G, Esente P. Effect of lipid-lowering therapy on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis assessed by scheduled repetitive coronary arteriography. Intern J Cardiol 1982; 2: 43–55.

Levy RI, Brensike JF, Epstein SE, Kelsey SF, Passamani ER, Richardson JM, Loh IK, Stone NJ, Aldrich RF, Battaglini JW, Moriarty DJ, Fisher ML, Friedman L, Friedewald W, Detre KM. The influence of changes in lipid values induced by cholestyramine and diet on progression of coronary artery disease: results of the NHLBI Type II Coronary Intervention Study. Circulation 1984; 69: 325–37.

Moise A, Théroux P, Taeymans J, Waters DD, Lespérance J, Fines P, Descoings B, Robert P. Clinical and angiographic factors associated with progression of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1984; 3: 659–67.

Nellessen U, Rafflenbeul W, Hecker H, Lichtlen P. The progression of coronary sclerosis. Six years of evaluation using quantitative coronary angiography in 19 patients. Z Kardiol 1984; 73: 760–7.

Arntzenius AC, Kromhout D, Barth JD, Reiber JHC, Bruschke AVG, Buis B, van Gent CM, Kempen-Voogd N, Strikwerda S, van der Velde EA. Diet, lipoproteins and the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. The Leiden intervention trial. N Engl J Med 1985; 312: 805–11.

Detre KM, Levy RI, Kelsey SF, Epstein SE, Brensike JF, Passamani ER, Richardson JM, Loh IK, Stone NJ, Aldrich RF, Battaglini JW, Moriarty DJ, Fischer ML, Friedman L, Friedewald W. Secondary prevention and lipid lowering: Results and implications. Am Heart J 1985; 110: 1123–7.

Blankenhorn DH, Nessim SA, Johnson RL, Sanmarco ME, Azen SP, Cashin-Hemphill LC. Beneficial effects of combined colestipol-niacin therapy on coronary atherosclerosis and coronary venous bypass grafts. JAMA 1987; 257: 3233–40.

Chesebro JH, Webster MWI, Smith HC, Frye RL, Holmes DR, Reeder GS, Bresnahan DR, Nishimura RA, Clements IP, Bardsley WT, Grill DE, Fuster V. Antiplatelet therapy in coronary disease progression: Reduced infarction and new lesion formation. Circulation 1989; 80 (suppl II): II-266.

Gottlieb SO, Brinker JA, Mellits ED, Achuff SC, Baughman KL, Traill TA, Weiss JL, Reitz BA, Weisfeldt ML, Gerstenblith G. Effect of nifedipine on the development of coronary bypass graft stenoses in high risk patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation 1989; 80 (suppl II): II-228.

Kober G, Schneider W, Kaltenbach M. Can the progression of coronary sclerosis be influenced by calcium antagonists? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1989; 13 (suppl 4): 2–6.

Loaldi A, Polese A, Montorsi P, De Cesare N, Fabbiocchi F, Ravagnani P, Guazzi MD. Comparison of nifedipine, propranolol and isosorbide dinitrate on angiographic progression and regression of coronary arterial narrowings in angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol 1989; 64: 433–9.

Brown G, Albers JJ, Fisher LD, Schefer SM, Lin JT, Kaplan Ch, Zhao XQ, Bisson BD, Fitzpatrick VF, Dodge HT. Regression of coronary artery disease as a result of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in men with high levels of apolipoprotein B. N Engl J Med 1990; 323: 1289–98.

Lichtlen PR, Hugenholtz PG, Rafflenbeul W, Hecker H, Jost S, Deckers JW. Retardation of the angiographic progression of coronary artery disease in man by the calcium channel blocker nifedipine -results of the International Nifedipine Trial on Antiatherosclerotic Therapy (IN-TACT). The Lancet 1990; 335: 1109–13.

Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, Armstrong WT, Ports TA, McLanahan SM, Kirkeeide RL, Brand RJ, Gould KL. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? Lancet 1990; 336: 129–33.

Waters D, Lespérance J, Francetich M, Causey D, Théroux P, Chiang YK, Hudon G, Lemarbre L, Reitman M, Joyal M, Gosselin G, Dyrda I, Macer J, Havel R. A controlled clinical trial to assess the effect of a calcium channel blocker upon the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation 1990; 82: 1940–53.

Bachelin R, Dumont J-M, Puttemans J, Lubsen J. Generic or specific data base system? The example of the MAAS trial. Eur Heart J 1990; 11, Abstract Suppl.: 216.

Kushi LH, Lew RA, Stare FJ, Ellisson CR, El Lozy M, Bourke G, Daly L, Graham I, Hiday N, Mulcahy R, Kevaney R. Diet and 20-year mortality from coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1985; 312: 811–8.

Canner PL, Berge KG, Wenger NK, Stamler J, Friedman L, Prineas RJ, Friedewald W. Fifteen year mortality in coronary drug project patients: Long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol 1986; 8: 1245–55.

Gordon DJ, Knoke J, Probstfield JL, Superko R, Tyroler HA. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and coronary heart disease in hypercholesterolemic men: The lipid research clinics coronary primary prevention trial. Circulation 1986; 74: 1217–25.

Frick MH, Elo O, Haapak M, Heinonen OP. Helsinki heart study: primary-prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle aged men with dyslipidemia. N Engl J Med 1987; 317: 1237–45.

Reiber JHC. Morphologic and densitometric quantitation of coronary stenoses; an overview of existing quantitation techniques. In: Reiber JHC, Serruys PW (eds). New developments in quantitative coronary arteriography. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Boston, London. 1988: 34–88.

Reiber JHC. An overview of coronary quantitation techniques as of 1989. In: Reiber JHC, Serruys PW (eds). Quantitative coronary arteriography. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Boston, London. 1991: 55–132.

Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini G, Gott VL, Griffith LSC, McGoon DG, Murphy ML, Roe BB. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease: report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery. American Heart Association. Circulation 1975; 51: 5–40.

Jenkins PJ, Harper RW, Nestel PJ. Severity of coronary atherosclerosis related to lipoprotein concentration. Brit Med J 1978; 2: 388–91.

Vlietstra RE, Kronmal RA, Frye RL, Seth AK, Tristani FE, Killip III T. Factors affecting the extent and severity of coronary artery disease in patients enrolled in the coronary artery surgery study. Arteriosclerosis 1982; 2: 208–15.

Favaloro RG. Computerized tabulation of cine coronary angiograms. Its implication for results of randomized trials. Circulation 1990; 81: 1992–2003.

Jost S, Deckers J, Nellessen U, Rafflenbeul W, Hecker H, Reiber JHC, Hugenholtz PG, Lichtlen PR. Clinical application of quantitative coronary angiography —preliminary results of the INTACT-study (International Nifedipine Trial on Antiatherosclerotic Therapy). Intern J Cardiac Imaging 1988; 3: 75–86.

Jost S, Deckers J, Rafflenbeul W, Hecker H, Nellessen U, Wiese B, Hugenholtz PG, Lichtlen PR, INTACT-study group. Features of the angiographic evaluation of the IN-TACT-study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1990; 4: 1037–46.

Lichtlen PR, Hugenholtz PG, Rafflenbeul W, Hecker H, Jost S, Nikutta P, Deckers W. Retardation of the progression of coronary artery disease in man by nifedipine; the INTACT-study (International Nifedipine Trial on Antiatherosclerotic Therapy). Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1990; 4: 1047–68.

Jost S, Deckers J, Rafflenbeul W, Hecker H, Reiber JHC, Nikutta P, Wiese B, Hugenholtz P, Lichtlen P, INTACT-group. International nifedipine trial on anti-atherosclerotic therapy (INTACT) -methodologic implications and results of a coronary angiographic follow-up study using computerassisted film analysis. Intern J Cardiac Imaging 1991; 6: 117–33.

Jost S, Deckers J, Nellessen U, Rafflenbeul W, Hecker H, Reiber JHC, Lippolt P, Hugenholtz PG, Lichtlen PR. Computer-assisted contour analysis technique in coronary angiographic follow-up trials: results of the first angiograms from the INTACT-study. Z Kardiol 1989; 78: 23–32.

Reiber JHC, Kooijman CJ, Slager CJ, Gerbrands JJ, Schuurbiers JCH, den Boer A, Wijns W, Serruys PW, Hugenholtz PG. Coronary artery dimensions from cineangiograms —methodology and validation of a computer-assisted analysis procedure. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1984; MI-3: 131–40.

Reiber JHC, Serruys PW, Kooijman CJ, Wijns W, Slager CJ, Gerbrands JJ, Schuurbiers JCH, den Boer A, Hugenholtz PG. Assessment of short-, medium-, and long-term variations in arterial dimensions from computer-assisted quantitation of coronary cineangiograms. Circulation 1985; 71: 280–8.

Jost S, Rafflenbeul W, Deckers J, Hecker H, Nikutta P, Wiese B, Hugenholtz P, Lichtlen PR, INTACT group. Angiographic assessment of the development of coronary artery disease with a geometrical method —Relevance of a high number of different projections. Eur Heart J 1990; 11 Abstract Suppl.: 372.

Scheffé H: The analysis of variance. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1959.

Jost S, Deckers J, Rafflenbeul W, Hecker H, Reiber JHC, Hugenholtz P, Lichtlen PR. Prospective quantitative angiographic follow-up of mild coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990; 15: 182A.

Faulkner SL, Fischer RD, Conkle DM, Page DL, Bender HW. Effect of blood flow rate on subendothelial proliferation in venous autografts used as arterial substitutes. Circulation 1975; 51/52 (suppl I): I163-I72.

Weiss HJ, Turitto VT, Baumgartner HR. Effect of shear rate on platelet interaction with subendothelium in citrated and native blood. I. Shear rate-dependent decrease of adhesion in von Willebrand's disease and the Bernard-Soulier syndrome. J Lab Clin Med 1978; 92: 750–64.

Friedman MH, Hutchins GM, Bargeron CB, Deters OJ, Mark FF. Correlation between intimal thickness and fluid shear in human arteries. Atherosclerosis 1981; 36: 263–74.

Davies MJ, Krikler DM, Katz D. Atherosclerosis: inhibition or regression as therapeutic possibilities. Br Heart J 1991; 65: 302–10.

Isner JM, Donaldson RF, Fortin AH, Tischler A, Clarke RH. Attenuation of the media of coronary arteries in advanced atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol 1986; 937–9.

Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins C, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 1371–5.

Stiel GM, Stiel LSG, Schofer J, Donath K, Mathey DG. Impact of compensatory enlargement of atherosclerotic coronary arteries on angiographic assessment of coronary artery disease. Circulation 1989; 80: 1603–9.

Jost S, Rafflenbeul W, Reil G-H, Trappe H-J, Gulba D, Hecker H, Gerhardt U, Knop I. Elimination of variable vasomotor tone in studies with repeated quantitative coronary angiography. Intern J Cardiac Imaging 1990; 5: 125–34.

Jost S, Rafflenbeul W, Knop I, Bossaller C, Gulba D, Hecker H, Lippolt P, Lichtlen PR. Drug plasma levels and coronary vasodilation after isosorbide dinitrate chewing capsules. Eur Heart J 1989; 10, Suppl F: 137–41.

Reiber JHC, van der Zwet PMJ, von Land CD, Koning G, Serruys PW, Loois G, Gerbrands JJ. Highly accurate and reproducible on-line coronary quantification. Eur Heart J 1990, 11, Abstract Suppl.: 373.

Reiber JHC, Zwet PMJ von der, Koning G, Land CF von, Padmos I, Buis B, Benthen AC van. Quantitative coronary measurements from cine and digital arteriography; methodology and validation results. 4th Int Symposium on Coronary Arteriography, Rotterdam, June 23–25, 1991: 36 (Abstract).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jost, S., Deckers, J., Rafflenbeul, W. et al. Quantitative angiographic follow-up studies on the development of coronary artery disease: which coronary segments should be analyzed?. Int J Cardiac Imag 9, 29–37 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01142930

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01142930