Abstract

Background

There are an increasing number of studies using simulation models to conduct cost-effectiveness analyses for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Objective

To evaluate the relationship between improvements in glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and simulated health outcomes in type 2 diabetes cost-effectiveness studies.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted on MEDLINE and EMBASE to collect cost-effectiveness studies using type 2 diabetes simulation models that reported modelled health outcomes of blood glucose-related interventions in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) or life expectancy (LE). The data extracted included information used to characterise the study cohort, the intervention’s treatment effects on risk factors and model outcomes. Linear regressions were used to test the relationship between the difference in HbA1c (∆HbA1c) and incremental QALYs (∆QALYs) or LE (∆LE) of intervention and control groups. The ratio between the ∆QALYs and ∆LE was calculated and a scatterplot between the ratio and ∆HbA1c was used to explore the relationship between these two.

Results

Seventy-six studies were included in this research, contributing to 124 pair of comparators. The pooled regressions indicated that the marginal effect of a 1% HbA1c decrease in intervention resulted in an increase in life-time QALYs and LE of 0.371 (95% confidence interval 0.286–0.456) and 0.642 (95% CI 0.494–0.790), respectively. No evidence of heterogeneity between models was found. An inverse exponential relationship was found and fitted between the ratio (∆QALY/∆LE) and ∆HbA1c.

Conclusion

There is a consistent relationship between ∆HbA1c and ∆QALYs or ∆LE in cost-effectiveness analyses using type 2 diabetes simulation models. This relationship can be used as a diagnostic tool for decision makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

There is a consistent relationship between treatment-effect assumptions on glycosylated haemoglobin and simulated outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus cost-effectiveness studies. |

A 1% glycosylated haemoglobin decrease in intervention results in an increase in life-time quality-adjusted life years and life expectancy of 0.371 and 0.642, respectively. |

This relationship can be used as a benchmark to identify studies deviating from others, and generate preliminary long-term effectiveness predictions when insufficient resources are available to use a simulation model. |

1 Introduction

Simulation modelling is a useful tool in health economic evaluation, especially for interventions targeted at treating chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus. Clinical trials of new therapies and behavioural interventions in type 2 diabetes often involve estimation on changes in intermediate-risk factors such as glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) [1, 2]. For these interventions to be evaluated using common health economic outcomes such as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), the potential benefits of observed improvements in metabolic control need to be extrapolated over longer time periods to capture impacts on the rates of complications of diabetes as well as mortality.

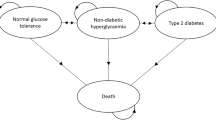

There is a long history in the use of simulation models to evaluate interventions for people with type 2 diabetes. The first simulation model for type 2 diabetes was built in 1997 by Eastman et al. [3, 4], which was based on clinical data from both type 2 and type 1 diabetes. Many models have been developed since then [5], and while many are based on the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Outcomes Model [6], there are differences in terms of model structure, particularly when they incorporate additional epidemiological and trial evidence to capture additional complications (e.g. impact of hypoglycaemia). A common feature of all these models is that they extrapolate changes in intermediate outcomes such as HbA1c to metrics such as QALYs or life expectancy (LE), which are most commonly used to capture outcomes in economic evaluations.

While most diabetes simulation models have been developed independently, the field has benefited from the diabetes simulation modelling conference ‘Mount Hood Diabetes Challenge’, which has been regularly held since 2000 to compare and contrast the outputs of models in a set series of simulations [7]. The last Mount Hood Diabetes Challenge meeting was held in 2014 and developers of 11 type 2 diabetes models participated, highlighting the development of simulation modelling in type 2 diabetes in recent years [8]. Diabetes simulation models are now widely used in cost-effectiveness studies and play an important role in defining clinical guidelines and the evaluation of new drugs [9].

Former reviews in type 2 diabetes cost-effectiveness studies have focused on summarising and describing the characteristics of different models [5, 10]. Currently, there are no studies that use quantitative techniques to evaluate the relationship between treatment-effect assumptions (e.g. a reduction in the level of HbA1c) and simulated outcomes (e.g. a gain in QALYs or LE). In this article, we systematically review cost-effectiveness studies of glycaemic control interventions that use type 2 diabetes simulation models to estimate long-term outcomes of QALYs or LE. Using data extracted from those studies, we use regression analysis to estimate the relationship between initial changes in HbA1c following the commencement of an intervention and model outputs. The objective of this research is to explore whether there is a consistent relationship between a widely reported intermediate outcome that is often used as an input in simulation models and model outputs across type 2 diabetes cost-effectiveness studies, and across different models.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Sources and Searches

We reviewed studies that involved use of a type 2 diabetes simulation model to inform a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) or cost-utility analysis (CUA) of blood glucose-lowering interventions that measured a change in HbA1c. All ten type 2 diabetes models that participated in the fourth (2004) or fifth (2010) Mount Hood Diabetes Challenge were considered to be eligible for inclusion in this study [11, 12], including the UKPDS Outcomes Model, IMS CORE Diabetes Model, Cardiff Model, Sheffield Diabetes Model, EAGLE Model, CDC-RTI Diabetes Cost-effectiveness Model, Archimedes Model, Michigan Model, ECHO-T2DM and the Evidence-Based Medicine Integrator Simulator. The UKPDS risk engine participated in the fourth Mount Hood Diabetes Challenge but was not included in this study as it does not quantify lifetime outcomes in terms of QALYs or LE [13]. Descriptions and further details of these models can be found in the Mount Hood Diabetes Challenge reports [11, 12].

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses recommendations and checklist were followed to conduct the systematic review [14]. Studies were identified by searching electronic databases, supplemented by scanning citations of the original publication of the ten targeted models and finally by contacting the model groups individually. The search was applied in two electronic databases, MEDLINE (1946 to present) and EMBASE (1947 to present) on Ovid. The subject heading ‘Diabetes Mellitus, Type2’ and other search terms including T2DM, cost effective*, cost utilit*, long term outcome*, long term consequence*, health economic*, health evaluation, economic evaluation, model*, simula*, QALY*, life year* and LE were used (see Supplementary Material 1 for full details on the search strategy).

2.2 Study Selection

The search was completed on 1 June, 2015 and included all published studies prior to that date. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

language in English;

-

reported outcomes were part of a CEA or CUA;

-

the study simulated outcomes based on one of the ten diabetes models mentioned above;

-

the population simulated in the model involved only people with type 2 diabetes;

-

the intervention focused on improvements in blood glucose control;

-

the primary treatment effect being modelled was the difference in HbA1c;

-

the study reported long-term (≥20 years) outcomes in either QALYs or LE.

Studies were excluded if:

-

language was not English;

-

it did not conduct CEA or CUA;

-

it used other established models or self-built models;

-

it included other populations (type 1 diabetes, pre-diabetes);

-

the intervention did not focus on improvements in blood glucose control or was a multifactorial intervention;

-

HbA1c was not used as the treatment effect or there was no difference in the reduction of HbA1c levels between the intervention and control group;

-

it did not report QALYs or LE as outcomes;

-

the outcomes were estimated only in the short term;

-

no discount rate was reported for the outcomes;

-

the study did not report the data necessary for this research (difference in HbA1c and incremental QALYs/LE).

Two reviewers (XH and LS) separately reviewed the studies by reading their abstracts and full texts. A third reviewer’s (PC) opinion was considered when there was a conflict of opinion between the first two. All but one of the Mount Hood modelling groups were contacted through email with a request for publications or a list of studies fitting our criteria (the EAGLE model group was excluded as no current contact details are available for its developers). A published model description paper was found for eight models (UKPDS [6], CORE [15], Cardiff [16], EAGLE [17], CDC [18], Archimedes [19], Michigan [20] and ECHO [21]). Studies that cited the aforementioned papers were scanned in Google Scholar, Web of Science and PubMed and added if they met our inclusion criteria.

2.3 Data Extraction

The intervention’s treatment effects on risk factors were extracted from each included study. Risk factors include HbA1c (%), body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), total cholesterol (mmol/L) and hypoglycaemic events (patient-year). The treatment effect is the difference in effect between the two groups. In some studies, this difference is directly reported; in other studies, they report the change in risk factors separately for each group. In the latter situation, we calculated the treatment effect by subtracting the two change values. Proper transformation was made when risk factors were not reported in the required unit (1 mmol/L = 38.6 mg/dL for total cholesterol). For eight studies [22–29], that only reported change in weight but not BMI as a treatment effect, the change in BMI was imputed using the cohort baseline height or 1.67 m as the default height (the average height for patients in the UKPDS [30]) if the cohort height was not reported in the study.

The model outcomes of interest in this study are QALYs and LE. Differences in QALYs (∆QALYs) and LE (∆LE) between the two groups in the base case were extracted from each study, as well as the discount rate used for the base case. Differences in undiscounted outcomes were also collected if they were available in the sensitivity analysis. We also extracted summary statistics of the study cohort, including the year of the study, comparators, cohort baseline age, diabetes duration and post-treatment HbA1c level in the control group. For studies that evaluated multiple comparisons, data of all these comparisons were included and collected. Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers (XH and LS). Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

2.4 Data Synthesis and Analysis

We conducted a basic descriptive analysis on the type of interventions, comparators and risk factors involved to summarise the identified studies. All analyses were conducted on undiscounted outcomes. Where studies only reported discounted outcomes, estimates of the undiscounted outcomes were imputed based on an algorithm that was developed from studies that reported both discounted and undiscounted outcomes (see Supplementary Material 4 for further description).

The relationship between ∆HbA1c and the difference in outcomes for comparators was examined using scatterplot and linear regression. Univariate regression was conducted initially for studies using different models separately. Then, a multivariable regression analysis was undertaken for all the studies. We used eight independent variables in the multivariable regression: difference in HbA1c, BMI, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, hypoglycaemic events; cohort baseline age; diabetes duration and post-treatment HbA1c level in the control group. Studies lacking information on these variables were excluded from the multivariable regression. Linearity of explanatory variables was checked and confirmed using multivariable fractional polynomials [31]. Interactions of each explanatory variable with HbA1c were checked by adding a multiplicative term into the regressions and no interactions were found. Statistical analysis took into account clustering by using the clustered robust standard errors method, owing to multiple comparisons coming from the same study. Before pooling studies that used different models together, the interaction effect between model type and ∆HbA1c on ∆QALYs and ∆LE was tested.

To test the coefficients of ∆HbA1c across multivariable regressions involving QALYs and LE, the equations were jointly estimated using STATA command MVREG (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) [32] and a Chi-square test was made. A significant difference between the two coefficients was confirmed. The ratio between ∆QALYs and ∆LE was then calculated and a scatterplot between the ratio and ∆HbA1c was built to explore the relationship between these two. Logarithm transformation of the ratio was made in an effort to fit the scatterplot. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 13.1 IC (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Summary of the Studies Included in the Analysis

Two hundred and eighty-eight studies were identified after applying our search strategy on MEDLINE and EMBASE and after abstract and full-text review, 65 publications were included in our study, as shown in Fig. 1. Our e-mail request resulted in ten extra studies, one from the ECHO model and nine using the CORE model and one additional study using the UKPDS Outcomes Model was identified through citation scanning. In total, 76 studies were included in this research, resulting in 124 pair of comparators [18, 22, 23, 25–29, 35–42, 44–103].

A summary of these studies can be found in Supplementary Material 2. Of the included studies, 43.4% evaluated the cost effectiveness of oral therapy drugs, 29.0% for insulin, 23.7% for management interventions and 3.9% (three studies) were not intervention specific. In addition, 22.4% of all included studies used HbA1c as the only treatment effect of the intervention. In recent years, other treatment effects such as BMI, blood pressure, hypoglycaemic events and lipid levels have increasingly been used, mainly in studies that evaluate cost effectiveness of new oral therapies; BMI and hypoglycaemic events are the two common effects besides HbA1c in insulin evaluation studies (see Figures S1 and S2 in Supplementary Material 3).

3.2 Relationship between Difference in HbA1c and the Outcomes

For the 76 studies included in this analysis, 75 reported QALYs as their model outcome and 59 studies reported LE as a simulation outcome. Forty-five studies (59.2%) reported undiscounted QALYs in their sensitivity analysis. The ratio values used for different discount rates to calculate undiscounted outcomes for the rest of the 31 studies (59/124 data points) can be found in Supplementary Material 4. One study [33] with four comparators was excluded from the QALYs regression analysis because it involved a large utility change in year 1 (0.152–0.312) as a direct treatment effect stemming from the intervention. This makes the relationship between HbA1c and QALY gain in this study not comparable to others, as other studies generally assumed changes in utility were mediated through changes in other risk factors such as BMI.

As only 19 studies used models other than the CORE model, those studies were combined together for the following regression analysis. Figure 2 depicts the scatterplots of differences in HbA1c and the difference in QALYs or LE in studies that use the CORE model and other models. A linear relationship could be found in these scatterplots.

The mean difference in HbA1c is 0.51%, while the mean increment in QALYs and LE are 0.409 and 0.389, respectively. The univariate regression results (Table 1) showed that for studies that used the CORE model, every 1% decrease in HbA1c from the intervention resulted in an increase of 0.455 and 0.808 for QALYs and LE, respectively. For studies that used the other models, every 1% decrease in HbA1c from the intervention resulted in a 0.352 increase in QALYs and a 0.696 increase in LE. No interaction effect was found between the models and a change in HbA1c (p = 0.557 for QALY; p = 0.234 for LE). After pooling all studies together, every 1% decrease in HbA1c from the intervention resulted in a 0.434 increase in QALYs and a 0.794 increase in LE. All the coefficients for HbA1c are significant at the 5% level.

Six studies were excluded from the multivariable regression because of a lack of information on age, diabetes duration or post-treatment HbA1c level in the control group [18, 38–42]. After controlling for all five risk factors and age, diabetes duration and post-treatment HbA1c level in the control group and pooling all studies together, ∆HbA1c, ∆BMI, ∆blood pressure and ∆hypoglycaemia events were the four variables with significant coefficients for ∆QALYs. Every 1% decrease in HbA1c from the intervention resulted in a 0.371 increase in QALYs. ∆HbA1c, ∆blood pressure and ∆total cholesterol were significant coefficients in the multivariable regression for LE. Every 1% decrease in HbA1c from the intervention resulted in a 0.642 increase in LE (Table 2).

The relationship between ∆HbA1c and the ratio of ∆QALYs and ∆LE can be found in Fig. 3. When the difference in HbA1c is small, the ratio between ∆QALYs and ∆LE increases dramatically. By transforming the dependent variable into ln(y), an inverse exponential relationship was found and fitted to the scatter graph.

4 Discussion

This study used regression analysis to estimate the association between changes in risk factors (e.g. HbA1c), which are common inputs for simulation models, and the estimated outcomes. The analysis is based on data from 76 studies obtained through a systematic review of published cost-effectiveness studies of blood glucose-lowering interventions for people with type 2 diabetes. Based on multiple linear regression that adjusted for a variety of metabolic risk factors, it found that the marginal effect of a 1% HbA1c decrease could result in life-time increases in QALYs and LE of 0.371 and 0.642, respectively. There was no evidence of heterogeneity between models. Studies reporting small differences in HbA1c tend to report larger gains for QALYs than LE, which implies that when the treatment effect on HbA1c is limited, the increase in QALYs mainly comes from utility gain, rather than longer life-years.

In this study, we mainly focus on the treatment effect of changes in HbA1c, as it is used in almost all analyses of blood glucose control interventions and is an input for all diabetes simulation models. Our review result suggests that recent economic evaluations of blood glucose-lowering interventions now use a wider variety of risk factors. For example, hypoglycaemic events, which have been incorporated into several models (CORE, Cardiff and ECHO) as an outcome of interest, were not captured in economic evaluations prior to 2006, but influence the outcomes of over 60% of the model simulations of blood glucose lowering in published studies during 2013–15 (Figure S1 in the Supplemental Material). We included these treatment effects into our multivariable regressions and found a significant relationship between them and model outputs as well. Furthermore, the relationship between the ratio of increase in QALYs and LE and a difference in HbA1c could be explained by the treatment effect on BMI and hypoglycaemia events. In addition to the impact on complications and death, the decrease in BMI and avoidance in adverse events themselves could also increase people’s quality of life [34] and appear to play a significant role in the outcomes of some recent economic evaluations of blood glucose control therapies [35, 36].

There are several potential practical applications of the relationship between a change in initial HbA1c and model outcomes found in this study. First, it can be used as a diagnostic tool or benchmark for decision makers, enabling them to identify analyses that deviate from the general trend and investigate whether there are other factors that may have led to the discrepancy and whether they are reasonable. Second, with limited information and resources to run a diabetes simulation model, the regression estimated in this study can be used to give a rough prediction of the long-term effectiveness that could be expected from an intervention in its early stages. In addition, beyond the specific results, this study provides a potential methodology for a meta-analytic approach to combining the results of cost-effectiveness studies based on simulated outcomes in the future.

This study has also highlighted inconsistencies in the reporting of assumptions regarding the treatment effect and in results of model simulations. To make cost-effectiveness simulation results transparent, the effect of treatment on all major risk factors should be reported over time. Currently, there is no standard way of reporting assumptions regarding the duration of an intervention effect on risk factors (e.g. some studies report an annual decay [37], while others a change at some future time [26]). The lack of consistent reporting has made it hard for us to incorporate this information into our regressions at this stage, thus we have been limited to using the initial change in HbA1c and other risk factors in our regression models. Three studies were excluded because the initial change in risk factors was not clearly reported. However, the main issue with the reporting of outcomes was that 40% of studies included in this analysis did not report their undiscounted results. Studies from different countries usually use different discount rates for their base case results, which makes the comparison between studies difficult to conduct. To address this issue, we calculated an average ratio between discounted and undiscounted ∆QALYs and used this to infer undiscounted outcomes when these were not reported. Basic cohort characteristics (age, duration of diabetes, proportion of male, ethnicity and other baseline risk factors) and model assumptions (time horizon) were also sometimes not reported. In this analysis, six studies were excluded from the multivariable regression because of a lack of information on age, diabetes duration or post-treatment HbA1c level in the control group [18, 38–42]. There is a clear need for general reporting standards of diabetes cost-effectiveness studies to be developed to promote transparency and facilitate future model comparisons. A starting point for this is the use of the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards [43].

This study is subject to a number of limitations. First, the difference in HbA1c collected in this study is the initial difference between two simulated cohorts, which is often the only measure of glycaemia that many simulation modelling studies included. While we note some simulation models make additional assumptions about the relative trajectory of HbA1c, most economic evaluations of diabetes therapies do not report these in a uniform manner and with insufficient details to be incorporated into the current analysis. While there is a strong association between initial HbA1c and long-term outcomes, the consistency of regression relationship depends on independence of the initial HbA1c and the error term. It would be useful to re-examine this assumption in future work, particularly as the transparency of reporting of simulation models improves over time.

Second, a lack of statistical power (124 pair of comparators) meant that we were unable to include many variables in the multivariable regression. Although other factors such as sex percentage, ethnicity and baseline values for other risk factors were also collected they were not included. Further, the limited number of studies using simulation models other than CORE meant we were unable to investigate the consistency between models separately. We found no evidence of heterogeneity between models by comparing studies that used the CORE model and studies that used any of the other type 2 diabetes simulation models. Again, there is scope for future work to include more control variables and further explore the consistency between models when more studies are available.

Finally, we have not taken account of reported uncertainty surrounding model estimates because of the limitations in the reporting of these measures in published studies. A future analysis could focus on comparisons of uncertainty by different simulation models.

5 Conclusion

We found a linear relationship between the difference in HbA1c and the difference in QALYs and LE based on published studies using type 2 diabetes models. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among models. When the difference in HbA1c is small, the gain in QALYs largely exceeds the gain in LE, suggesting when the treatment effect on HbA1c is limited, the increase in QALYs mainly comes from utility gain, rather than longer life-years. Our study provides a benchmark for decision makers to identify studies deviating from others, and potentially generate preliminary long-term effectiveness predictions when insufficient resources are available to use a simulation model.

References

Aschner P, Chan J, Owens DR, et al. Insulin glargine versus sitagliptin in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus uncontrolled on metformin (EASIE): a multicentre, randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2262–9.

Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes)-2 study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):84–90.

Eastman RC, Javitt JC, Herman WH, et al. Model of complications of NIDDM. I. Model construction and assumptions. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(5):725–34.

Eastman RC, Javitt JC, Herman WH, et al. Model of complications of NIDDM. II. Analysis of the health benefits and cost-effectiveness of treating NIDDM with the goal of normoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(5):735–44.

Yi Y, Philips Z, Bergman G, Burslem K. Economic models in type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(9):2105–18.

Clarke P, Gray A, Briggs A, et al. A model to estimate the lifetime health outcomes of patients with type 2 diabetes: the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Outcomes Model (UKPDS no. 68). Diabetologia. 2004;47(10):1747–59.

Brown JB, Palmer AJ, Bisgaard P, et al. The Mt. Hood challenge: cross-testing two diabetes simulation models. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;50:S57–64.

Mt Hood Challenge Group. Economics modelling and diabetes:The Mount Hood 2014 Challenge. http://www.mthooddiabeteschallenge.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Mt-Hood-2014-Program-CIRCULATION.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2015.

Conditions NCCfC. Type 2 diabetes: national clinical guideline for management in primary and secondary care (update). London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2008.

Asche CV, Hippler SE, Eurich DT. Review of models used in economic analyses of new oral treatments for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(1):15–27.

Mount H. Computer modeling of diabetes and its complications: a report on the Fourth Mount Hood Challenge Meeting. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1638.

Palmer AJ, Group MHM. Computer modeling of diabetes and its complications: a report on the Fifth Mount Hood challenge meeting. Value Health. 2013;16(4):670–85.

Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, et al. Group UKPDS. The UKPDS risk engine: a model for the risk of coronary heart disease in type II diabetes (UKPDS 56). Clin Sci. 2001;101(6):671–9.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W-65-W-94.

Palmer AJ, Roze S, Valentine WJ, et al. The CORE Diabetes Model: projecting long-term clinical outcomes, costs and costeffectiveness of interventions in diabetes mellitus (types 1 and 2) to support clinical and reimbursement decision-making. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(S1):S5–26.

McEwan P, Peters JR, Bergenheim K, Currie CJ. Evaluation of the costs and outcomes from changes in risk factors in type 2 diabetes using the Cardiff stochastic simulation cost-utility model (DiabForecaster). Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;22(1):121–9.

Mueller E, Maxion-Bergemann S, Gultyaev D, et al. Development and validation of the Economic Assessment of Glycemic Control and Long-Term Effects of diabetes (EAGLE) model. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2006;8(2):219–36.

Group CDCDC-e. Cost-effectiveness of intensive glycemic control, intensified hypertension control, and serum cholesterol level reduction for type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2002;287(19):2542–51.

Eddy DM, Schlessinger L. Archimedes: a trial-validated model of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):3093–101.

Zhou H, Isaman DJ, Messinger S, et al. A computer simulation model of diabetes progression, quality of life, and cost. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(12):2856–63.

Willis M, Asseburg C, He J. Validation of economic and health outcomes simulation model of type 2 diabetes mellitus (ECHO-T2DM). J Med Econ. 2013;16(8):1007–21.

Gao L, Zhao FL, Li SC. Cost-utility analysis of liraglutide versus glimepiride as add-on to metformin in type 2 diabetes patients in China. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(4):436–44.

Waugh N, Cummins E, Royle P, et al. Newer agents for blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(36):1–248.

Lee WC, Samyshkin Y, Langer J, Palmer JL. Long-term clinical and economic outcomes associated with liraglutide versus sitagliptin therapy when added to metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a CORE Diabetes Model analysis. J Med Econ. 2012;15(Suppl 2):28–37.

Grzeszczak W, Czupryniak L, Kolasa K, et al. The cost-effectiveness of saxagliptin versus NPH insulin when used in combination with other oral antidiabetes agents in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Poland. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(1):65–73.

Elgart JF, Caporale JE, Gonzalez L, et al. Treatment of type 2 diabetes with saxagliptin: a pharmacoeconomic evaluation in Argentina. Health Econ Rev. 2013;3(1):11.

Granstrom O, Bergenheim K, McEwan P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of saxagliptin (Onglyza) in type 2 diabetes in Sweden. Prim Care Diabetes. 2012;6(2):127–36.

Erhardt W, Bergenheim K, Duprat-Lomon I, McEwan P. Cost effectiveness of saxagliptin and metformin versus sulfonylurea and metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Germany: a Cardiff diabetes model analysis. Clin Drug Invest. 2012;32(3):189–202.

Van Haalen HGM, Pompen M, Bergenheim K, et al. Cost effectiveness of adding dapagliflozin to insulin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Netherlands. Clin Drug Invest. 2014;34(2):135–46.

Group UPDS. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–53.

Sauerbrei W, Royston P. Building multivariable prognostic and diagnostic models: transformation of the predictors by using fractional polynomials. J R Stat Soc Series A. 1999;162(1):71–94.

StataCorp. Stata 13 base reference manual. College Station: Stata; 2013.

Shafie AA, Gupta V, Baabbad R, et al. An analysis of the short-and long-term cost-effectiveness of starting biphasic insulin aspart 30 in insulin-naïve people with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106(2):319–27.

Matza LS, Boye KS, Yurgin N, et al. Utilities and disutilities for type 2 diabetes treatment-related attributes. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(7):1251–65.

Mittendorf T, Smith-Palmer J, Timlin L, et al. Evaluation of exenatide vs. insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes: cost-effectiveness analysis in the German setting. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(11):1068–79.

Tunis SL, Minshall ME, Conner C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of insulin detemir compared to NPH insulin for type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Canadian payer setting: modeling analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(5):1273–84.

Lee WC, Conner C, Hammer M. Results of a model analysis of the cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus exenatide added to metformin, glimepiride, or both for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in the United States. Clin Ther. 2010;32(10):1756–67.

Cameron C, Coyle D, Ur E, Klarenbach S. Cost-effectiveness of self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus managed without insulin. CMAJ. 2010;182(1):28–34.

Palmer AJ, Roze S, Valentine WJ, et al. Impact of changes in HbA1c, lipids and blood pressure on long-term outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients: an analysis using the CORE Diabetes Model. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(Suppl 1):S53–8.

Brownson CA, Hoerger TJ, Fisher EB, Kilpatrick KE. Cost-effectiveness of diabetes self-management programs in community primary care settings. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(5):761–9.

Ryabov I. Cost-effectiveness of community health workers in controlling diabetes epidemic on the U.S.-Mexico border. Public Health. 2014;128(7):636–42.

Gillett M, Dallosso HM, Dixon S, et al. Delivering the diabetes education and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c4093.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS): explanation and elaboration. A report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(2):231–50.

Afzali HHA, Gray J, Beilby J, et al. A model-based economic evaluation of improved primary care management of patients with type 2 diabetes in Australia. Appl Health Econom Health Policy. 2013;11:661–70.

Gilmer TP, O’Connor PJ, Sperl-Hillen JM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an electronic medical record based clinical decision support system. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2137–58. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01427.x.

Gillespie P, O’Shea E, Paul G, et al. Cost effectiveness of peer support for type 2 diabetes. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(1):3–11.

Coyle D, Coyle K, Kenny GP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of exercise programs in type 2 diabetes. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(3):228–34.

Tunis SL. Cost effectiveness of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) for patients with type 2 diabetes and not on insulin. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2011;9:351–65.

Brown ST, Grima DG, Sauriol L. Cost-effectiveness of insulin glargine versus sitagliptin in insulin-naïve patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2014;36(11):1576–87.

Tzanetakos C, Melidonis A, Verras C, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of liraglutide versus sitagliptin or exenatide in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes on oral antidiabetic drugs in Greece. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):419.

Shafie AA, Gupta V, Baabbad R, et al. An analysis of the short- and long-term cost-effectiveness of starting biphasic insulin aspart 30 in insulin-naïve people with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;16(7):926–38.

Giorda C, Nicolucci A, Pellegrini F, et al. Improving quality of care in people with type 2 diabetes through the Associazione Medici Diabetologi-annals initiative: a long-term cost-effectiveness analysis. Diabet Med. 2014;31(5):615–23.

Fonseca T, Clegg J, Caputo G, et al. The cost-effectiveness of exenatide once weekly compared with exenatide twice daily and insulin glargine for the treatment of patients with type two diabetes and body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 in Spain. J Med Econ. 2013;16(7):926–38.

Raya PM, Pérez A, de Arellano AR, et al. Incretin therapy for type 2 diabetes in Spain: a cost-effectiveness analysis of liraglutide versus sitagliptin. Diabetes Ther. 2013;4(2):417–30.

Pollock R, Muduma G, Valentine W. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding versus standard medical management in obese patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2013;15(2):121–9.

Davies M, Chubb B, Smith I, Valentine W. Cost-utility analysis of liraglutide compared with sulphonylurea or sitagliptin, all as add-on to metformin monotherapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2012;29(3):313–20.

Guillermin A-L, Lloyd A, Best JH, et al. Long-term cost-consequence analysis of exenatide once weekly vs sitagliptin or pioglitazone for the treatment of type 2 diabetes patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2012;15(4):654–63.

Lee WC, Samyshkin Y, Langer J, Palmer JL. Long-term clinical and economic outcomes associated with liraglutide versus sitagliptin therapy when added to metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a CORE Diabetes Model analysis. J Med Econ. 2012;15(s2):28–37.

Pollock RF, Curtis BH, Valentine WJ. A long-term analysis evaluating the cost-effectiveness of biphasic insulin lispro mix 75/25 and mix 50/50 versus long-acting basal insulin analogs in the United States. J Med Econ. 2012;15(4):766–75.

Pollock RF, Curtis BH, Smith-Palmer J, Valentine WJ. A UK analysis of the cost-effectiveness of Humalog Mix75/25 and Mix50/50 versus long-acting basal insulin. Adv Ther. 2012;29(12):1051–66.

Samyshkin Y, Guillermin A-L, Best JH, et al. Long-term cost-utility analysis of exenatide once weekly versus insulin glargine for the treatment of type 2 diabetes patients in the US. J Med Econ. 2012;15(s2):6–13.

Smith-Palmer J, Fajardo-Montanana C, Pollock R, et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness of insulin detemir versus NPH insulin in type 2 diabetes in Sweden. J Med Econ. 2012;15(5):977–86.

Valov V, Palmer J, Czech M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of biphasic insulin aspart 30 VS. human premix insulin in type 2 diabetes from the payer’s perspective in Bulgaria. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2012;26(2):2937–44.

Yang L, Christensen T, Sun F, Chang J. Cost-effectiveness of switching patients with type 2 diabetes from insulin glargine to insulin detemir in Chinese setting: a health economic model based on the PREDICTIVE study. Value Health. 2012;15(1 Suppl):S56–9.

Beaudet A, Palmer JL, Timlin L, et al. Cost-utility of exenatide once weekly compared with insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK. J Med Econ. 2011;14(3):357–66.

Goodall G, Costi M, Timlin L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of exenatide versus insulin glargine in Spanish patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Nutr. 2011;58(7):331–40.

Lee WC, Conner C, Hammer M. Cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus rosiglitazone, both in combination with glimepiride in treatment of type 2 diabetes in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):897–906.

Valentine WJ, Palmer AJ, Lammert M, et al. Evaluating the long-term cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus exenatide BID in patients with type 2 diabetes who fail to improve with oral antidiabetic agents. Clin Ther. 2011;33(11):1698–712.

Palmer JL, Beaudet A, White J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of biphasic insulin aspart versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes in China. Adv Ther. 2010;27(11):814–27.

Palmer JL, Knudsen MS, Aagren M, Thomsen TL. Cost-effectiveness of switching to biphasic insulin aspart from human premix insulin in a US setting. J Med Econ. 2010;13(2):212–20.

Pollock RF, Valentine WJ, Goodall G, Brändle M. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of self-monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes patients on oral anti-diabetic agents. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140:36.

Tunis SL, Sauriol L, Minshall ME. Cost effectiveness of insulin glargine plus oral antidiabetes drugs compared with premixed insulin alone in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Canada. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2010;8(4):267–80.

Tunis SL, Willis WD, Foos V. Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) in patients with type 2 diabetes on oral anti-diabetes drugs: cost-effectiveness in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(1):163–75.

Tunis SL, Minshall ME. Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) for type 2 diabetes patients treated with oral anti-diabetes drugs and with a recent history of monitoring: cost-effectiveness in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(1):151–62.

Brandle M, Erny-Albrecht KM, Goodall G, et al. Exenatide versus insulin glargine: a cost-effectiveness evaluation in patients with type 2 diabetes in Switzerland. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;47(8):501–15.

Brandle M, Goodall G, Erny-Albrecht KM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pioglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes and a history of macrovascular disease in a Swiss setting. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139(11–12):173–84.

Cameron CG, Bennett HA. Cost-effectiveness of insulin analogues for diabetes mellitus. CMAJ. 2009;180(4):400–7.

Goodall G, Sarpong EM, Hayes C, Valentine WJ. The consequences of delaying insulin initiation in UK type 2 diabetes patients failing oral hyperglycaemic agents: a modelling study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2009;9(1):19.

Lee KH, Seo SJ, Smith-Palmer J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of switching to biphasic insulin aspart 30 from human insulin in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes in South Korea. Value Health. 2009;12(s3):S55–61.

Scherbaum WA, Goodall G, Erny-Albrecht KM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pioglitazone in type 2 diabetes patients with a history of macrovascular disease: a German perspective. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2009;7:9. doi:10.1186/1478-7547-7-9.

Valentine WJ, Tucker D, Palmer AJ, et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness of pioglitazone versus placebo in addition to existing diabetes treatment: a US analysis based on PROactive. Value Health. 2009;12(1):1–9.

St Charles M, Minshall ME, Pandya BJ, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of pioglitazone plus metformin compared with rosiglitazone plus metformin from a third-party payer perspective in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(6):1343–53.

Ali M, White J, Lee CH, et al. Therapy conversion to biphasic insulin aspart 30 improves long-term outcomes and reduces the costs of type 2 diabetes in Saudi Arabia. J Med Econ. 2008;11(4):651–70.

Chirakup S, Chaiyakunapruk N, Chaikledkeaw U, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of thiazolidinediones in uncontrolled type 2 diabetic patients receiving sulfonylureas and metformin in Thailand. Value Health. 2008;11(s1):S43–51.

Goodall G, Jendle J, Valentine W, et al. Biphasic insulin aspart 70/30 vs. insulin glargine in insulin naïve type 2 diabetes patients: modelling the long-term health economic implications in a Swedish setting. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(6):869–76.

Minshall ME, Oglesby AK, Wintle ME, et al. Estimating the long-term cost-effectiveness of exenatide in the United States: an adjunctive treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Value Health. 2008;11(1):22–33.

Palmer JL, Gibbs M, Scheijbeler HW, et al. Cost-effectiveness of switching to biphasic insulin aspart in poorly-controlled type 2 diabetes patients in China. Adv Ther. 2008;25(8):752–74.

Palmer JL, Goodall G, Nielsen S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of insulin aspart versus human soluble insulin in type 2 diabetes in four European countries: subgroup analyses from the PREDICTIVE study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(5):1417–28.

Valentine WJ, Goodall G, Aagren M, et al. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of therapy conversion to insulin detemir in patients with type 2 diabetes in Germany: a modelling study of long-term clinical and cost outcomes. Adv Ther. 2008;25(6):567–84.

Tunis SL, Minshall ME. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes: cost-effectiveness in the united states. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(3):131–40.

Tunis SL, Minshall ME, St Charles M, et al. Pioglitazone versus rosiglitazone treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia: cost-effectiveness in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3085–96.

Gilmer TP, Roze S, Valentine WJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diabetes case management for low-income populations. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(5):1943–59.

Ray JA, Boye KS, Yurgin N, et al. Exenatide versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK: a model of long-term clinical and cost outcomes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(3):609–22.

Ray J, Valentine W, Roze S, et al. Insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes patients failing oral agents: cost‐effectiveness of biphasic insulin aspart 70/30 vs. insulin glargine in the US. Diabet Obes Metab. 2007;9(1):103–13.

Valentine WJ, Erny-Albrecht KM, Ray JA, et al. Therapy conversion to insulin detemir among patients with type 2 diabetes treated with oral agents: a modeling study of cost-effectiveness in the United States. Adv Ther. 2007;24(2):273–90.

Valentine WJ, Bottomley JM, Palmer AJ, et al. PROactive 06: cost-effectiveness of pioglitazone in type 2 diabetes in the UK. Diabet Med. 2007;24(9):982–1002.

Palmer AJ, Dinneen S, Gavin JR, et al. Cost-utility analysis in a UK setting of self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(5):861–72.

Roze S, Valentine WJ, Evers T, Palmer AJ. Acarbose in addition to existing treatments in patients with type 2 diabetes: health economic analysis in a German setting. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(7):1415–24.

Valentine W, Palmer A, Nicklasson L, et al. Improving life expectancy and decreasing the incidence of complications associated with type 2 diabetes: a modelling study of HbA1c targets. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(9):1138–45.

Valentine WJ, Palmer AJ, Lammert M, et al. Long-term clinical and cost outcomes of treatment with biphasic insulin aspart 30/70 versus insulin glargine in insulin naive type 2 diabetes patients: cost-effectiveness analysis in the UK setting. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(12):2063–71.

Palmer AJ, Roze S, Lammert M, et al. Comparing the long-term cost-effectiveness of repaglinide plus metformin versus nateglinide plus metformin in type 2 diabetes patients with inadequate glycaemic control: an application of the CORE Diabetes Model in type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(S1):S41–51.

Neslusan C, Teschemaker A, Johansen P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of canagliflozin versus sitagliptin as add-on to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Mexico. Value Health Regional. 2015;8:8–19.

Hoerger TJ, Zhang P, Segel JE, et al. Improvements in risk factor control among persons with diabetes in the United States: evidence and implications for remaining life expectancy. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2009;86(3):225–32.

Data Availability Statement

All the data underpinning this systematic review analysis were collected from published studies. This has been uploaded and is available in the electronic supplementary material.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work is supported by Xinyang Hua’s PhD scholarship: Melbourne International Research Scholarship from the University of Melbourne and some supplementary funding from two National Health and Medical Research Council project grants (GNT1084347; GNT1107140). No other funding has been received for the conduct of this study.

Conflict of interest

Philip Clarke has intellectual property in the UKPDS outcomes model and Andrew Palmer was involved in the development of the CORE diabetes model. Xinyang Hua, Thomas Lung, Lei Si and William Herman declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Xinyang Hua designed the research, reviewed studies, extracted and analysed data, and drafted the manuscript. Thomas Lung designed the research and drafted the manuscript. Andrew Palmer designed the research and provided critical revision of the manuscript. Lei Si reviewed studies and extracted data. William Herman provided critical revision of the manuscript. Philip Clarke designed the research, supervised the study and helped review studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hua, X., Lung, T.WC., Palmer, A. et al. How Consistent is the Relationship between Improved Glucose Control and Modelled Health Outcomes for People with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus? a Systematic Review. PharmacoEconomics 35, 319–329 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0466-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0466-0