Abstract

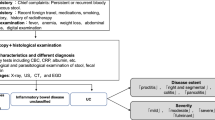

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract of unknown etiology that frequently presents in the pediatric population. The evaluation of pediatric UC involves excluding infection, and a colonoscopy that documents the clinical and histologic features of chronic colitis. Initial management of mild UC is typically with mesalamine therapy for induction and maintenance. Moderate UC is often initially treated with oral prednisone. Depending on disease severity and response to prednisone, maintenance options include mesalamine, mercaptopurine, azathioprine, infliximab, or adalimumab. Severe UC is typically treated with intravenous corticosteroids. Corticosteroid nonresponders should either undergo a colectomy or be treated with second-line medical rescue therapy (infliximab or calcineurin inhibitors). The severe UC patients who respond to medical rescue therapy can be maintained on infliximab or thiopurine, but 1-year remission rates for such patients are under 50 %. These medications are discussed in detail along with the initial work-up and a treatment algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Turner D, Griffiths AM. Acute severe ulcerative colitis in children: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(1):440–9.

Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College Of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):501–23 (quiz 24).

Bousvaros A, Antonioli DA, Colletti RB, et al. Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(5):653–74.

Loftus CG, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(3):254–61.

Haskell H, Andrews CW Jr, Reddy SI, et al. Pathologic features and clinical significance of “backwash” ileitis in ulcerative colitis. Am J Surgical Pathol. 2005;29(11):1472–81.

Matsui T, Yao T, Sakurai T, et al. Clinical features and pattern of indeterminate colitis: Crohn’s disease with ulcerative colitis-like clinical presentation. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(7):647–55.

Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, et al. The ESPGHAN revised Porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000000239.

Jess T, Loftus EV Jr, Velayos FS, et al. Risk of intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study from Olmsted county, Minnesota. Gastroenterol. 2006;130(4):1039–46.

Turner D, Otley AR, Mack D, et al. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterol. 2007;133(2):423–32.

Cuffari C, Dubinsky M, Seidman EG. Clinical roundtable monograph: the evolving role of serologic markers in the management of pediatric IBD. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;5(2 Suppl 6):1–14.

Inoue T, Murano M, Narabayashi K, et al. The efficacy of oral tacrolimus in patients with moderate/severe ulcerative colitis not receiving concomitant corticosteroid therapy. Intern Med. 2013;52(1):15–20.

Autenrieth DM, Baumgart DC. Toxic megacolon. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(3):584–91.

Turner D, Travis SP, Griffiths AM, et al. Consensus for managing acute severe ulcerative colitis in children: a systematic review and joint statement from ECCO, ESPGHAN, and the Porto IBD Working Group of ESPGHAN. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):574–88.

Zeisler B, Lerer T, Markowitz J, et al. Outcome following aminosalicylate therapy in children newly diagnosed as having ulcerative colitis. J Pediatric Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56(1):12–8.

Burger D, Travis S. Conventional medical management of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. 2011;140(6):1827–37 e2.

Sonu I, Lin MV, Blonski W, et al. Clinical pharmacology of 5-ASA compounds in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39(3):559–99.

Peppercorn MA. Sulfasalazine: pharmacology, clinical use, toxicity, and related new drug development. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101(3):377–86.

Fujiwara M, Mitsui K, Ishida J, et al. The effect of salazosulfapyridine on the in vitro antibody production in murine spleen cells. Immunopharmacology. 1990;19(1):15–21.

Doering J, Begue B, Lentze MJ, et al. Induction of T lymphocyte apoptosis by sulphasalazine in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2004;53(11):1632–8.

Dubuquoy L, Rousseaux C, Thuru X, et al. PPARgamma as a new therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2006;55(9):1341–9.

Pedersen G, Brynskov J. Topical rosiglitazone treatment improves ulcerative colitis by restoring peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(7):1595–603.

Rousseaux C, Lefebvre B, Dubuquoy L, et al. Intestinal anti-inflammatory effect of 5-aminosalicylic acid is dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. J Exp Med. 2005;201(8):1205–15.

Levine A, de Bie CI, Turner D, et al. Atypical disease phenotypes in pediatric ulcerative colitis: 5-year analyses of the EUROKIDS Registry. Inflam Bowel Dis. 2013;19(2):370–7.

Moss AC, Cheifetz AS, Peppercorn M. A combined oral and topical mesalazine treatment for extensive ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3(5):290–3.

Marshall JK, Thabane M, Steinhart AH, et al. Rectal 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(11):CD004118.

Marshall JK, Irvine EJ. Rectal corticosteroids versus alternative treatments in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 1997;40(6):775–81.

D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Barrett K, et al. Once-daily MMX® mesalamine for endoscopic maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1064–77.

Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. BMJ. 1955;2(4947):1041–8.

Beattie RM, Nicholls SW, Domizio P, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the colonic response to corticosteroids in children with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;22(4):373–9.

Baron JH, Connell AM, Kanaghinis TG, et al. Out-patient treatment of ulcerative colitis: comparison between three doses of oral prednisone. BMJ. 1962;2(5302):441–3.

Hyams J, Markowitz J, Lerer T, et al. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for ulcerative colitis in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(9):1118–23.

Buchman AL. Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33(4):289–94.

Harris DM. Some properties of beclomethasone dipropionate and related steroids in man. Postgrad Med J. 1975;51(Suppl 4):20–5.

Bansky G, Buhler H, Stamm B, et al. Treatment of distal ulcerative colitis with beclomethasone enemas: high therapeutic efficacy without endocrine side effects. A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30(4):288–92.

Romano C, Famiani A, Comito D, et al. Oral beclomethasone dipropionate in pediatric active ulcerative colitis: a comparison trial with mesalazine. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50(4):385–9.

Brunner M, Ziegler S, Di Stefano AF, et al. Gastrointestinal transit, release and plasma pharmacokinetics of a new oral budesonide formulation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61(1):31–8.

Gross V, Bunganic I, Belousova EA, et al. 3 g mesalazine granules are superior to 9 mg budesonide for achieving remission in active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(2):129–38.

Tiede I, Fritz G, Strand S, et al. CD28-dependent Rac1 activation is the molecular target of azathioprine in primary human CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(8):1133–45.

Hyams JS, Lerer T, Mack D, et al. Outcome following thiopurine use in children with ulcerative colitis: a prospective multicenter registry study. A J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(5):981–7.

Louis E, Belaiche J. Optimizing treatment with thioguanine derivatives in inflammatory bowel disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17(1):37–46.

Derijks LJ, Gilissen LP, Hooymans PM, et al. Review article: thiopurines in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(5):715–29.

Dubinsky MC, Lamothe S, Yang HY, et al. Pharmacogenomics and metabolite measurement for 6-mercaptopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(4):705–13.

Cuffari C, Hunt S, Bayless T. Utilisation of erythrocyte 6-thioguanine metabolite levels to optimise azathioprine therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2001;48(5):642–6.

Osterman MT, Kundu R, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Association of 6-thioguanine nucleotide levels and inflammatory bowel disease activity: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(4):1047–53.

Pearson DC, May GR, Fick GH, et al. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn disease: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(2):132–42.

Curkovic I, Rentsch KM, Frei P, et al. Low allopurinol doses are sufficient to optimize azathioprine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease patients with inadequate thiopurine metabolite concentrations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(8):1521–31.

Rahhal RM, Bishop WP. Initial clinical experience with allopurinol-thiopurine combination therapy in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(12):1678–82.

Shih DQ, Nguyen M, Zheng L, et al. Split-dose administration of thiopurine drugs: a novel and effective strategy for managing preferential 6-MMP metabolism. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(5):449–58.

Chande N, MacDonald JK, McDonald JW. Methotrexate for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006618.

Jolivet J, Cowan KH, Curt GA, et al. The pharmacology and clinical use of methotrexate. New Engl J Med. 1983;309(18):1094–104.

Ravikumara M, Hinsberger A, Spray CH. Role of methotrexate in the management of Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(4):427–30.

Morabito L, Montesinos MC, Schreibman DM, et al. Methotrexate and sulfasalazine promote adenosine release by a mechanism that requires ecto-5′-nucleotidase-mediated conversion of adenine nucleotides. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(2):295–300.

Genestier L, Paillot R, Fournel S, et al. Immunosuppressive properties of methotrexate: apoptosis and clonal deletion of activated peripheral T cells. J Clin Investig. 1998;102(2):322–8.

Cronstein BN. The mechanism of action of methotrexate. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1997;23(4):739–55.

Khan N, Abbas AM, Moehlen M, et al. Methotrexate in ulcerative colitis: a nationwide retrospective cohort from the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(7):1379–83.

Cummings JR, Herrlinger KR, Travis SP, et al. Oral methotrexate in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(4):385–9.

Oren R, Arber N, Odes S, et al. Methotrexate in chronic active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, randomized Israeli multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(5):1416–21.

Aloi M, Di Nardo G, Conte F, et al. Methotrexate in paediatric ulcerative colitis: a retrospective survey at a single tertiary referral centre. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(8):1017–22.

Jakobsen C, Bartek J Jr, Wewer V, et al. Differences in phenotype and disease course in adult and paediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1217–24.

Wilson A, Patel V, Chande N, et al. Pharmacokinetic profiles for oral and subcutaneous methotrexate in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(3):340–5.

Ho S, Clipstone N, Timmermann L, et al. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;80(3 Pt 2):S40–5.

Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(26):1841–5.

Palestine AG, Austin HA 3rd, Balow JE, et al. Renal histopathologic alterations in patients treated with cyclosporine for uveitis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(20):1293–8.

Fox DS, Cruz MC, Sia RA, et al. Calcineurin regulatory subunit is essential for virulence and mediates interactions with FKBP12-FK506 in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39(4):835–49.

Ogata H, Kato J, Hirai F, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral tacrolimus (FK506) in the management of hospitalized patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(5):803–8.

Watson S, Pensabene L, Mitchell P, et al. Outcomes and adverse events in children and young adults undergoing tacrolimus therapy for steroid-refractory colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(1):22–9.

Breese EJ, Michie CA, Nicholls SW, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-producing cells in the intestinal mucosa of children with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1994;106(6):1455–66.

Viallard JF, Pellegrin JL, Ranchin V, et al. Th1 (IL-2, interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma)) and Th2 (IL-10, IL-4) cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115(1):189–95.

Ringheanu M, Markowitz J. Inflammatory bowel disease in children. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2002;5(3):181–96.

Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2462–76.

Hyams J, Damaraju L, Blank M, et al. Induction and maintenance therapy with infliximab for children with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(4):391–9 e1.

Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(15):1383–95.

Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:392–400.

Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):257–65 e1–3.

Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al. 52-week efficacy of adalimumab in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis who failed corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(8):1700–9.

Afif W, Loftus EV Jr, Faubion WA, et al. Clinical utility of measuring infliximab and human anti-chimeric antibody concentrations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(5):1133–9.

Acknowledgements/Conflicts of Interest

A. Bousvaros has received research grants from Prometheus, Merck, and UCB, has consulted for Dyax, Millenium, Cubist, UCB, and Nutricia, is on the speakers bureau for Merck, and has received royalties from UpToDate. B. Regan declares no conflicts of interest. No sources of funding were used to prepare this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Regan, B.P., Bousvaros, A. Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis: A Practical Guide to Management. Pediatr Drugs 16, 189–198 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-014-0070-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-014-0070-8