Abstract

Background and Objectives

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling for itraconazole has been challenging due to highly variable in vitro d ata used for ‘bottom-up’ model building. Under-prediction of pharmacokinetics and drug–drug interactions (DDIs) following multiple doses of itraconazole has limited the use of PBPK model simulation to aid an itraconazole clinical DDI study design. The aim of this work is to develop an itraconazole PBPK model predominantly using a ‘top-down’ approach to enable a more accurate pharmacokinetic and DDI prediction.

Methods

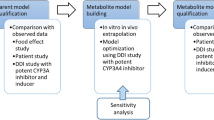

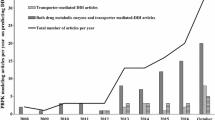

An itraconazole PBPK model describing itraconazole and hydroxyl-itraconazole (OH-ITZ) was constructed in Simcyp®. The key parameters that govern the pharmacokinetic profile, including non-linear clearance (i.e., maximum rate of reaction [V max] and the Michaelis-Menten constant [K m]) and volume of distribution for both itraconazole and OH-ITZ, were redefined by leveraging existing in vivo data. Model verification was performed by comparing the simulated itraconazole and OH-ITZ pharmacokinetic profiles with the observed clinical data. Finally, the model was used to simulate clinical DDIs between itraconazole and midazolam.

Results

The developed PBPK model well-described the pharmacokinetics of itraconazole and OH-ITZ, and particularly captured their accumulation after repeated doses of itraconazole. This was verified with the observed data from 29 clinical studies where itraconazole solution or capsule was given as a single or multiple dose. The predicted DDI between itraconazole and midazolam was within 1.25-fold of the observed data for seven of ten studies and within 1.5-fold for nine of ten studies.

Conclusion

The improvement of the itraconazole PBPK model increased our confidence in using PBPK model simulations to optimize clinical itraconazole DDI study design.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Han B, Mao J, Chien JY, Hall SD. Optimization of drug-drug interaction study design: comparison of minimal physiologically based pharmacokinetic models on prediction of CYP3A inhibition by ketoconazole. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41(7):1329–38.

Zhao P, Ragueneau-Majlessi I, Zhang L, Strong JM, Reynolds KS, Levy RH, et al. Quantitative evaluation of pharmacokinetic inhibition of CYP3A substrates by ketoconazole: a simulation study. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49(3):351–9.

Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Drug interaction studies—study design, data analysis, implications for dosing, and labeling recommendations. 2012. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm292362.pdf. Accessed June 2015.

European Medicine Agency. Guideline on the investigation of drug interactions. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2012/07/WC500129606.pdf. Accessed June 2015.

Ke AB, Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Higgins JW, Hall SD. Itraconazole and clarithromycin as ketoconazole alternatives for clinical CYP3A inhibition studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95(5):473–6.

Olkkola KT, Ahonen J, Neuvonen PJ. The effects of the systemic antimycotics, itraconazole and fluconazole, on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous and oral midazolam. Anesth Analg. 1996;82(3):511–6.

Olkkola KT, Backman JT, Neuvonen PJ. Midazolam should be avoided in patients receiving the systemic antimycotics ketoconazole or itraconazole. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55(5):481–5.

Heykants J, Van Peer A, Van de Velde V, Van Rooy P, Meuldermans W, Lavrijsen K, et al. The clinical pharmacokinetics of itraconazole: an overview. Mycoses. 1989;32(Suppl 1):67–87.

Poirier JM, Cheymol G. Optimisation of itraconazole therapy using target drug concentrations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1998;35(6):461–73.

Templeton I, Peng CC, Thummel KE, Davis C, Kunze KL, Isoherranen N. Accurate prediction of dose-dependent CYP3A4 inhibition by itraconazole and its metabolites from in vitro inhibition data. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88(4):499–505.

Isoherranen N, Kunze KL, Allen KE, Nelson WL, Thummel KE. Role of itraconazole metabolites in CYP3A4 inhibition. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32(10):1121–31.

Mouton JW, van Peer A, de Beule K, Van Vliet A, Donnelly JP, Soons PA. Pharmacokinetics of itraconazole and hydroxyitraconazole in healthy subjects after single and multiple doses of a novel formulation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(12):4096–102.

Templeton IE, Thummel KE, Kharasch ED, Kunze KL, Hoffer C, Nelson WL, et al. Contribution of itraconazole metabolites to inhibition of CYP3A4 in vivo. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(1):77–85.

Van Peer A, Woestenborghs R, Heykants J, Gasparini R, Gauwenbergh G. The effects of food and dose on the oral systemic availability of itraconazole in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;36(4):423–6.

Van de Velde VJ, Van Peer AP, Heykants JJ, Woestenborghs RJ, Van Rooy P, De Beule KL, et al. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of a new hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin formulation of itraconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16(3):424–8.

Barone JA, Moskovitz BL, Guarnieri J, Hassell AE, Colaizzi JL, Bierman RH, et al. Enhanced bioavailability of itraconazole in hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin solution versus capsules in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42(7):1862–5.

Gubbins PO, Gurley BJ, Williams DK, Penzak SR, McConnell SA, Franks AM, et al. Examining sex-related differences in enteric itraconazole metabolism in healthy adults using grapefruit juice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(3):293–301.

Barone JA, Moskovitz BL, Guarnieri J, Hassell AE, Colaizzi JL, Bierman RH, et al. Food interaction and steady-state pharmacokinetics of itraconazole oral solution in healthy volunteers. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18(2):295–301.

Gubbins PO, McConnell SA, Gurley BJ, Fincher TK, Franks AM, Williams DK, et al. Influence of grapefruit juice on the systemic availability of itraconazole oral solution in healthy adult volunteers. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(4):460–7.

Kousoulos C, Tsatsou G, Apostolou C, Dotsikas Y, Loukas YL. Development of a high-throughput method for the determination of itraconazole and its hydroxy metabolite in human plasma, employing automated liquid-liquid extraction based on 96-well format plates and LC/MS/MS. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;384(1):199–207.

Yun HY, Baek MS, Park IS, Choi BK, Kwon KI. Comparative analysis of the effects of rice and bread meals on bioavailability of itraconazole using NONMEM in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(12):1033–9.

Hardin TC, Graybill JR, Fetchick R, Woestenborghs R, Rinaldi MG, Kuhn JG. Pharmacokinetics of itraconazole following oral administration to normal volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32(9):1310–3.

Bharathi DV, Hotha KK, Sagar PV, Kumar SS, Reddy PR, Naidu A, et al. Development and validation of a highly sensitive and robust LC-MS/MS with electrospray ionization method for simultaneous quantitation of itraconazole and hydroxyitraconazole in human plasma: application to a bioequivalence study. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;868(1–2):70–6.

Woestenborghs R, Lorreyne W, Heykants J. Determination of itraconazole in plasma and animal tissues by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1987;413:332–7.

Uno T, Shimizu M, Sugawara K, Tateishi T. Sensitive determination of itraconazole and its active metabolite in human plasma by column-switching high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(4):526–31.

Bae SK, Park SJ, Shim EJ, Mun JH, Kim EY, Shin JG, et al. Increased oral bioavailability of itraconazole and its active metabolite, 7-hydroxyitraconazole, when coadministered with a vitamin C beverage in healthy participants. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51(3):444–51.

Barone JA, Koh JG, Bierman RH, Colaizzi JL, Swanson KA, Gaffar MC, et al. Food interaction and steady-state pharmacokinetics of itraconazole capsules in healthy male volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37(4):778–84.

Lange D, Pavao JH, Wu J, Klausner M. Effect of a cola beverage on the bioavailability of itraconazole in the presence of H2 blockers. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(6):535–40.

Ohkubo T, Osanai T. Determination of itraconazole in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with solid-phase extraction. Ann Clin Biochem. 2005;42(Pt 2):94–8.

Miura M, Takahashi N, Nara M, Fujishima N, Kagaya H, Kameoka Y, et al. A simple, sensitive high-performance liquid chromatography-ultraviolet method for the quantification of concentration and steady-state pharmacokinetics of itraconazole and hydroxyitraconazole. Ann Clin Biochem. 2010;47(Pt 5):432–9.

Ahonen J, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ. Effect of itraconazole and terbinafine on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of midazolam in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;40(3):270–2.

Backman JT, Kivistö KT, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve for oral midazolam is 400-fold larger during treatment with itraconazole than with rifampicin. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54(1):53–8.

Lombardo F, Obach RS, Shalaeva MY, Gao F. Prediction of human volume of distribution values for neutral and basic drugs. 2. Extended data set and leave-class-out statistics. J Med Chem. 2004;47(5):1242–50.

Rowland Yeo K, Jamei M, Yang J, Tucker GT, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Physiologically based mechanistic modelling to predict complex drug-drug interactions involving simultaneous competitive and time-dependent enzyme inhibition by parent compound and its metabolite in both liver and gut—the effect of diltiazem on the time-course of exposure to triazolam. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;39(5):298–309.

Toi A, Ohtani H, Tsujimoto M, Sawada Y. Pharmacokinetic modeling of the dosing interval dependency for the interaction between itraconazole and triazolam. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48(6):356–66.

Yoo SD, Kang E, Jun H, Shin BS, Lee KC, Lee KH. Absorption, first-pass metabolism, and disposition of itraconazole in rats. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2000;48(6):798–801.

Waterhouse TH, Redmann S, Duffull SB, Eccleston JA. Optimal design for model discrimination and parameter estimation for itraconazole population pharmacokinetics in cystic fibrosis patients. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2005;32(3–4):521–45.

Arredondo G, Suárez E, Calvo R, Vazquez JA, García-Sanchez J, Martinez-Jordá R. Serum protein binding of itraconazole and fluconazole in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43(2):305–7.

Ishigam M, Uchiyama M, Kondo T, Iwabuchi H, Inoue S, Takasaki W, et al. Inhibition of in vitro metabolism of simvastatin by itraconazole in humans and prediction of in vivo drug-drug interactions. Pharm Res. 2001;18(5):622–31.

Liu L, Bello A, Dresser MJ, Heald D, Komjathy SF, O’Mara E, et al. Best practices for the use of itraconazole as a replacement for ketoconazole in drug-drug interaction studies. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015. doi:10.1002/jcph.562 (Epub 2015 Jun 4).

Author contributions

Participated in model design: YC and FM. Collected data and ran simulations: YC, FM, and TL. Performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript: YC, FM, TL, HW, and JM. Reviewed the manuscript and approved for submission: YC, FM, TL, NB, JYJ, JRK, HW, CH, and JM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was funded by Genentech (a member of the Roche group). All authors (YC, FM, TL, NB, JYJ, JRK, HW, CH, JM) were employees of Genentech when this work was carried out. They have no other conflicts of interest to declare. We would like to thank Tao Ji for participating in the discussions. We especially thank Karen R. Yeo from Simcyp (a Certara company) for sharing her experience related to the itraconazole model assessment during scientific discussion at Simcyp consortium meetings.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

40262_2015_352_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary material 1 (PDF 650 kb) Fig. 1S—best fit parameter estimation (PE) curve generated by Simcyp model using data from IV administration of ITZ (Mouton et al., 2006): i—50 mg ITZ PK; ii—100 mg ITZ PK, iii—200 mg ITZ PK; iv—300 mg ITZ PK. For observed 100mg PK data (a) Mouton et al., 2006 (b) Heykants, et al., 1989. Fig. 2S—Simulated and observed plasma concentration-time profiles of OH-ITZ formed from IV administration of ITZ at 50 (i), 100 (ii), 200 (iii), and 300 mg (iv). Simulated mean is the mean of 100 individuals (10 trials of 10 subjects per trial); simulated trial is the mean of 10 subjects in each trial; 5th–95th percentile for 100 individuals simulated represents the 5th and 95th highest concentrations from the ranked concentrations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Ma, F., Lu, T. et al. Development of a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model for Itraconazole Pharmacokinetics and Drug–Drug Interaction Prediction. Clin Pharmacokinet 55, 735–749 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-015-0352-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-015-0352-5