Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is sensitive to lesion formation both in the brain and spinal cord. Imaging plays a prominent role in the diagnosis and monitoring of MS. Over a dozen anti-inflammatory therapies are approved for MS and the development of many of these medications was made possible through the use of contrast-enhancing lesions on MRI as a phase II outcome. A similar phase II outcome method for the neurodegeneration that underlies progressive courses of the disease is still unavailable. Although magnetic resonance is an invaluable tool for the diagnosis and monitoring of treatment effects in MS, several imaging barriers still exist. In general, MRI is less sensitive to gray matter lesions, lacks pathological specificity, and does not provide quantitative data easily. Several advanced imaging methods including diffusion tensor imaging, magnetization transfer, functional MRI, myelin water fraction imaging, ultra-high field MRI, positron emission tomography, and optical coherence tomography of the retina study promising ways of overcoming the difficulties in MS imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Significant advances have been made in the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) over the last 20 years with the development of over a dozen disease-modifying medications [1]. This accomplishment was aided by the availability of an imaging biomarker for relapsing forms of the disease. New lesion formation was able to predict the response to anti-inflammatory medications [2]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has emerged as the most useful biomarker in relapsing forms of MS. In contrast, there are no validated imaging biomarkers to measure therapeutic benefit in progressive forms of MS, although several candidate MRI measures hold promise. Many challenges remain in the application of imaging to MS, including the optimal MRI measure for progressive forms of MS, the low sensitivity for detection of cortical lesions, and the somewhat limited sensitivity even in white matter disease. In this review, we will review the data demonstrating the evidence of MRI as a biomarker in MS, as well as several candidate imaging biomarkers which hold promise for the future.

Brain MRI Measures

Lesional Measures

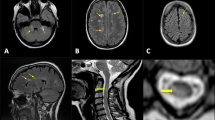

The association of clinical relapses with focal lesion development was recognized through the use of MRI [3]. In the earliest studies, it became clear that MRI disease activity was more common than clinical relapses [4]. From a statistical standpoint, an average of 10 to 15 new brain lesions are formed for every 1 clinical relapse [5]. This opened the possibility of using new lesion formation on MRI as a potential mechanism to screen for early disease activity and to measure the effect of anti-inflammatory therapies. The volumetric assessment of T2 lesions in aggregate is considered a measure of the overall burden of the disease and is associated with clinical disability. MRI is able to provide some temporal data on lesion formation. New lesion formation is pathologically characterized by perivenular inflammatory infiltrates with variable amounts of myelin loss and axonal injury. This focal breakdown of the blood–brain barrier can be visualized on MRI as areas of contrast enhancement on T1-weighted images and is the radiological hallmark of new lesion formation. This enhancement typically has a duration of 4 to 8 weeks [6], and provides temporal information in MS. Contrast enhancement is useful in determining dissemination in time criterion, even when using a single MRI [7]. Similarly, classifying MS lesions based on their T1 signal has been proposed as a way to assess the degree of tissue injury. T1 hypointense lesions, also known as “black holes”, have been found to have significant loss of axons and are associated with disability measures [8, 9]. Lesion localization appears to be important in predicting disability, with periventricular lesion load being a predictor of disability [10]. Localization of lesions in the brain stem has been associated with increased level of disability and appears to be a strong predictor of clinical conversion to definite in patients with a single demyelinating episode, also known as clinically isolated syndrome [11]. Lesion load and new lesion formation are key features of the McDonald 2010 criteria and MS can now be diagnosed after a first clinical event with a single MRI scan; this reveals the prognostic power of the imaging technique as a biomarker of disease course [7]. There have been recent modifications to the application of MRI findings to the dissemination in time and space criteria for the diagnosis of MS (Table 1) [12]. A previous requirement that only asymptomatic gadolinium-enhancing lesions could be used to fulfill criteria has been dropped, as there was not a major change to specificity and sensitivity. Dissemination in space criteria now can use both cortical lesions and optic nerve lesions, and the number of periventricular lesions needed has been increased to 3.

To date, new lesion activity is arguably the best biomarker of active inflammation in MS identified. A clear relationship between lesion development and relapses is best evidenced when examining clinical trials of MS disease-modifying therapy. Sormani et al. [2, 13] conducted several meta-analytical studies correlating the effect of disease-modifying treatments on new lesions and relapses (Fig. 1). From an analysis of 31 trials and > 18,000 individuals, they found that a treatment’s effect on new or enlarging T2 lesions was highly predictive of its effect on relapses (R2 = 0.71). Additionally, treatment effects on lesion development predicted a treatment effect on relapses both in the short term (6–9 months), as well as in the longer term (12–24 months). Using a similar meta-analysis method, the same group found the combination of an effect on MRI and relapses predicted an effect on disability as measured by confirmed worsening on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [13]. The authors conclude that MRI lesions and relapses can function as a surrogate measure for disability. These analyses have validated the use of new MRI lesions (new or enlarged T2 and new gadolinium lesions) as the primary outcome of phase II trials of anti-inflammatory therapies in relapsing forms of MS.

Meta-analysis of 31 trials (circles) with regression (lines) plotted shows the effect of relapses based on the effects on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Log(MRIeffect) is logarithm of the MRI lesion rate ratio. Permission from Sormani et al. [2]

The development of new lesions during treatment with disease-modifying therapies has predictive properties. Among patients treated with interferon (IFN)-β1a, the presence of gadolinium-enhancing lesions and new T2 lesions during the first few years of therapy predicted disability worsening over 15 years [14]. Although there is agreement that new lesion development during IFN therapy predicts worse clinical outcome, the appropriate cut-off for number of new lesions that predict poor outcome is not clear. A similar validation of new lesion formation predicting poor outcome during treatment with newer MS therapies is not yet available. However, given that all currently approved medications appear to exert their effects through prevention of new focal demyelinating lesions, it is likely this observation will hold across different medications. The combination of relapses and new MRI lesions has been shown to predict response to interferon therapy and long-term outcomes [15]. The modified Rio Score is a clinical tool that assigns points based on the presence and quantity of new lesions and relapses and has been proposed as a useful tool in clinical practice.

The evidence that lesion formation is a predictor of disease activity in relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) and is a predictor of response to anti-inflammatory therapies has made MRI one of the most useful clinical practice tools in MS. Clinicians use MRI to detect subclinical disease activity and make changes before clinical relapses occur. MRI measures form part of the concept of “no evidence of disease activity” (NEDA). NEDA is a state in which patients do not have new/enlarging T2 lesions, gadolinium-enhancing lesions, clinical relapses, or disability progression [16, 17]. NEDA is now being accepted as a target for treatment in patients with RRMS [18, 19]. New lesion formation is the most common reason for patients to leave NEDA status, and this observation highlights the importance of MRI a clinically useful biomarker in MS.

The identification of central veins from MS lesions has been proposed as a sensitive diagnostic tool for the disease. Central veins may help differentiate MS lesions from nonspecific white matter lesions and from lesions that may occur in the context of migraine headaches. Central veins are most easily appreciated using ultra-high field imaging and also can be seen at 3T, particularly with the help of specialized T2* imaging sequences [20]. Mistry et al. [21] established a set of rules for the use of central veins for diagnosis of MS (Table 2). Validation of these rules is still needed, but the presence of central veins within focal T2 lesions may aid clinicians when the diagnosis of MS is in question.

Brain Atrophy

Measurement of whole brain or regional atrophy using MRI has been advocated as a method to assess both diffuse tissue injury in MS, as well as aggregate tissue injury (i.e., the summation of both focal and diffuse injury). Although lesions provide a reasonable biomarker of inflammatory disease activity in MS, there is no similar measure in progressive MS. Atrophy measures hold promise as potential biomarkers for more diffuse neurodegenerative processes in progressive MS.

There are several methods available to quantify whole brain atrophy. In general, brain tissue volume needs to be normalized for cranial volume, and assessment of longitudinal changes require some type of co-registration methods to identify changes over time. Registration-based methods involve comparing longitudinally acquired images and measuring changes in brain surface. Common registration-based techniques include structural image evaluation using normalization of atrophy (SIENA) and statistical parametric mapping. Segmentation-based techniques commonly involve direct measurement of brain volume in a single scan, the values of which can be compared over time. Segmentation-based techniques include brain parenchymal fraction and SIENAX, among others.

Whole brain atrophy measures have shown modest correlations and some predictive properties with overall disability scores including EDSS and Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite [22, 23]. Whole brain atrophy has demonstrated correlations with cognitive function [24, 25]. The effect of whole brain atrophy has been examined in treatment trials of MS. In RRMS, results have not shown a consistent correlation between atrophy and effect on relapses. The explanation for this dissociation may relate to the biological mechanism of the different anti-inflammatory medications, use of several different atrophy detection methods, and heterogeneity in the clinical characteristics of the subjects. A paradoxical decrease in brain volume during the first months of treatment, also known as “pseudo atrophy”, has been observed for several anti-inflammatory disease-modifying agents [26]. Pseudo atrophy complicates analysis of brain atrophy and requires following atrophy over long periods (i.e., 2 years) to mitigate this effect. Additionally, as MS progresses, atrophy is probably driven more by neurodegenerative changes than focal lesions and relapses, which could explain the limited association between these measures.

Because of its aggregate measurement qualities, brain atrophy has been proposed as a potential outcome measure in phase II studies of neuroprotective medications and in progressive MS. Atrophy is likely a good global measure of neurodegenerative processes in MS, and standardized methodology make its application easily feasible across several centers. Proposed sample sizes for neuroprotection derived from whole brain atrophy have been published, with estimated sample sizes between 80 and 398 subjects per treatment arm in RRMS [27]. For secondary progressive MS (SPMS) trials, similar estimates have been proposed using SIENA, with as few as 32 patients required per arm to detect a 50% treatment effect [28]. Although atrophy is an attractive outcome measure for progressive forms of the disease, the sample size estimates noted above are calculated using quite large effect sizes. Atrophy can be viewed as a relatively final effect in the pathway of neurodegeneration, and markers that detect brain injury prior to actual tissue loss may be advantageous in detecting early neuroprotective treatment effects. Brain atrophy has been proposed to be incorporated into the traditional NEDA measures, commonly referred to as NEDA-4 [29]. However, because atrophy measurements are typically not conducted in routine clinical practice and given the difficulty in establishing a meaningful atrophy progression threshold, the use of atrophy in NEDA will have limited utility in clinical settings for now.

Gray Matter Atrophy

Regional atrophy measures have emerged as more specific markers of the disease progress. Instead of examining whole brain atrophy, segmenting white matter and gray matter independently has shown improvements in the association and prediction of disability over time. Measurement of gray matter atrophy can be conducted using similar methodology as described for whole brain atrophy. Specifically, atrophy in both deep and cortical gray matter, have demonstrated stronger correlations with clinical disability than white matter atrophy, even over 20 years of disease evolution [30]. Gray matter atrophy occurs early in MS and correlates with lesion load better than white matter atrophy [30–32]. Gray matter atrophy is found in a gradient with increasing severity in clinically isolated syndrome, RRMS, and SPMS (as compared with healthy controls), while white matter atrophy appears to be relatively constant of the disease course. Mechanisms of direct injury, as well as antegrade and retrograde axonal degeneration, has been hypothesized for the gray matter in MS—even in radiologically isolated syndrome gray matter volume is reduced [33]. Gray matter atrophy demonstrates stronger correlations with cognitive function [34, 35].

Another way of assessing cortical atrophy is through measurement of cortical thickness. Cortical thickness can be determined using several semiautomated techniques, perhaps the most widely used being FreeSurfer [36, 37]. Some technical challenges exist as misclassification of lesion tissue with cortex is common, and some methods have been developed to overcome this problem, including in painting of lesions [38], and algorithms that incorporate lesions maps into deformable cortical models [39].

Several studies have explored the contribution of specific deep gray matter nuclei in MS. The thalamus changes from very early stages of disease, including radiologically isolated syndrome [40] and pediatric populations [41]. Thalamic atrophy has been correlated with neuropsychological function [42–44], ambulation [45], and fatigue [46]. The hippocampus shows atrophy in all stages of MS and is associated with deficits in memory encoding and retrieval [47]. Hippocampal atrophy has been described in pediatric MS and appears to be regional, with selective vulnerability of the cornu ammonis, subiculum, and dentate gyrus, rather than global. In pediatric MS hippocampal regional atrophy correlates with attention and language function. Similarly, caudate atrophy has been described in MS [48], and an increase in the bicaudate ratio has been found to predict impaired cognitive function [49].

Gray Matter Lesions

Although focal white matter lesions are predominant in MS, gray matter demyelination has been described. Cortical gray matter lesions have been extensively identified on pathological specimens of both early and late stages of MS [50, 51]. Lesions have been classified based on their location as type I (cortical, juxtacortical), type II (intracortical lesion without extension to the surface of the brain or white matter), type III (band-like subpial lesions), and type IV (intracortical full width of the cortex without subcortical white matter involvement) [51–53]. Cortical lesions appear to differ pathologically from white matter lesions, as they contain fewer inflammatory infiltrates, transected neurites, and apoptotic neurons [51]. These pathological differences likely explain why these lesions are not easily identified on conventional MRI studies [54]. In a postmortem study, only 32% of lesions detected histologically were evidenced on conventional MRI [55]. Focal disruption of the blood–brain barrier does not seem to occur with new formation of cortical lesions and, hence, lesions are not typically contrast enhancing. Despite these limitations, several imaging sequences have been developed to improve the sensitivity of cortical lesions detection. Double inversion recovery, which provides an inversion for both white matter and cerebrospinal fluid, helps in the detection of intracortical lesions and precise localization of cortical/juxta cortical lesions [56]. Ultra-high field imaging provides improved detection of cortical lesions with greater anatomic resolution and differentiation of lesions seen with double inversion recovery. Seven Tesla (T) also permits differentiation of extracortical blood vessels, which can be confused with cortical lesions [57]. Several studies have found an association between cortical lesion load and cognitive function both at 3 T [58] and at 7 T [57].

Gray matter lesions have been identified in deep brain structures. On pathological examination focal demyelination accounted for about 15% (range 0.2–31.6%) of the deep gray matter in patients with RRMS [59]. Deep gray matter lesions many times involve both white and gray matter with an intermediate amount of inflammation between cortical lesions and white matter lesions. Even early MRI studies suggested that approximately 5% of total lesion volume came from deep gray matter structures [60]. In the thalamus, for example, a recent 7 T study found lesions in approximately 70% of patients with MS [61]. Thalamic lesions were described as either discrete/ovoid or lining the ventricle. Thalamic lesion load was found to correlate with EDSS and with cortical lesion load.

Advanced MRI Methods

In addition to standard MRI methods, several “advanced” MRI measures have been proposed with the promise of developing more sensitive and specific markers for MS. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a quantitative technique that permits the characterization of water motion through the application of multiple diffusion gradients [62]. In DTI water motion is modeled to yield measures of axial, radial, and mean diffusivity, as well as overall diffusion anisotropy (fractional anisotropy). DTI permits the characterization of tissue architecture with radial diffusivity corresponding roughly to myelin content [63, 64], and axial diffusivity corresponding to integrity of axons [65]. Several longitudinal DTI studies have demonstrated progressive increase in radial diffusivity over time [66, 67]. Additionally, DTI measures have been shown to predict black hole formation [66, 68], and lesion formation from normal appearing white matter [69]. Tract-based DTI measures improve prediction of disability over conventional MRI measures. DTI has been assessed across multiple scanners/platforms and is being used in multicenter studies of progressive MS [70]. More complex modeling of diffusion data may enable determination of more specific tissue properties, including axon density and neurites [71]. DTI may have role in trials assessing overall brain tissue integrity and testing neuroprotectant medications.

Functional MRI (fMRI) provides signal related to brain activation based on blood oxygen consumption and blood flow in brain tissue. fMRI has been immensely useful in understanding how brain structures are connected and how injury in different brain regions correlate. fMRI has served as an important tool in addressing cognitive function in MS [72]. In relation to cognition it appears people with MS initially exhibit increased connectivity as a compensatory mechanism; however, over time, connectivity in the severely diseased MS brain tends to decrease [73]. fMRI studies also were able to demonstrate the reorganization of brain function during cognitive tasks with MS [74]. Several studies have used fMRI to integrate both diffusion and atrophy changes to better explain cognitive dysfunction and disability [75, 76].

Magnetization transfer imaging involves measurement of the transfer of magnetization between the free and bound proton pool in tissue [77]. Magnetization transfer imaging involves applying 2 sequences: 1 with a magnetization transfer pulse and 1 without. The images are then subtracted with a resultant magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) image. MTR has been proposed as a measure of myelin content [78]; however, MTR may be measuring water content as well [79]. MTR in white matter lesions has a predictable and biological time course consistent with demyelination and remyelination [80]. MTR has been shown to be sensitive to demyelination in the cortex [81] and deep gray matter [82]. MTR from normal-appearing brain tissue has been associated with clinical disability [83], although a stronger clinical association of lesional MTR over normal-appearing tissue has been reported [84]. MRI is sensitive to water content and methods have been developed to identify water located between the lipid bilayers of myelin. From whole brain water measures of myelin water fraction based on multiexponential T2 decay can been derived using several methods with promising results in MS [85, 86]. MTR and water myelin fraction may have a significant role in trials using purported remyelinating agents.

Sodium imaging using MRI is a novel technique that involves using the magnetic resonance signal of 23NA. This imaging modality is of interest as several studies have suggested that intraxonal accumulation of sodium may relate to axonal degeneration [87]. Sodium imaging requires a special MRI nuclear coil with significant postprocessing for determination of sodium concentrations. Sodium imaging using ultra-high field MRI has been employed in MS, and intracellular sodium increases from lesions have been associated with clinical disability [88]. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy allows the characterization of the metabolic function of brain tissue through assessment of metabolites such as N-acetyl aspartate, creatine, and choline. Differences between healthy controls and patients with RRMS and SPMS using this technique have been well documented [89]. Several longitudinal studies have demonstrated that the relation between disability and assessment of N-acetyl aspartate to creatine ratios [90]. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy has been proposed as a method to monitor tissue injury both from lesions and normal-appearing white matter [91]. Newer methods examining γ-glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA spectroscopy) have been attempted in MS and may carry greater pathological specificity [92, 93].

Spinal Cord MRI

The spinal cord is a prominent site of injury in MS and spinal cord lesions are a strong predictor of disability. In the spinal cord, unlike the brain, there is more limited neuroplasticity and few clinically silent regions. This may explain the stronger correlations between spinal cord imaging and disability compared with brain imaging. However, several factors have complicated the use of spinal cord imaging in MS, including low spatial resolution, physiological movements, partial volume averaging, and the disappearance of cord lesions over time [94, 95]. Despite these limitations, and with improvements in technology, spinal cord imaging holds great promise as a biomarker in MS. Although lesions occur less frequently in the spinal cord than in the brain [96], lesions of the spinal cord tend to show a greater individual correlation with disability [97, 98].The presence of spinal cord lesions is a strong predictor of developing MS among patients with clinically isolated syndrome, with 1 study showing an odds ratio of 14.4 for developing clinically definite MS in the presence of spinal cord pathology [99]. In radiologically isolated syndrome, the presence of asymptotic spinal cord lesions was associated with an odds ratio of 75.3 for development of clinically isolated syndrome or primary progressive MS [100]. This last observation highlights the fact that spinal cord lesions may occur asymptomatically and may be worth monitoring for response to disease-modifying treatment. Spinal cord volume appears to be a good differentiating tool between relapsing and progressive MS disease course [101]. Upper cervical cord cross-sectional area was found to be one of the strongest predictors of disability [97, 102]. Longitudinal assessment of spinal cord atrophy has demonstrated good correlation with changes in disability [103]. Cervical atrophy has already been used as an outcome measure in at least 1 neuroprotection trial, where the active agent riluzole decreased the rate of cervical cord atrophy [104]. Similar to what is observed in brain, regional changes in the spinal cord also seem to be important, with several groups describing changes in the posterior and lateral segments of the cord [105, 106].

Several advanced MRI imaging techniques have been applied to the spinal cord and have shown promising results. DTI measures derived from the cervical spinal cord were found to correlate and predict hip flexion strength and vibratory sensation [107]. DTI tractography of the corticospinal tract has shown correlation with disability [108]. MTR from gray matter in the spinal cord correlates strongly with disability measures [109]. A more recent study shows that MTR from pial and subpial regions of the spinal cord correlates with spinal cord atrophy and shows a biological gradient across MS disease courses [110]. Spectroscopy of the spinal cord can be used to identify changes in metabolite profiles both from lesions and nonlesional tissue [108, 111].

The application of ultra-high field imaging in spinal cord provides an increased resolution for better anatomic characterization, which is particularly evident on axial images [112]. Ultra-high field imaging of the spinal cord helps to better discriminate white and gray matter, as well as individual lesion in the cervical spine, with some studies showing an increase in lesion detection of > 50% [113]. Similar to what is observed in brain, lesions in spinal cord gray matter can be more easily visualized at high field [114]. Water myelin mapping of the spinal cord at 7 T holds promise as a more specific marker with excellent resolution at 7 T [115].

Positron Emission Tomography Imaging in MS

The use of radioligand compounds to look for specific pathological substrates has been proposed and studied in MS [116]. Chemical compounds are labelled with positron-emitting isotopes which can be imaged in tissue using a positron camera [117]. Positron emission tomography (PET) technology can be combined with computed tomography or MRI to provide improved anatomic localization. Several imaging targets have been proposed in MS and PET may be the most direct way to quantify pathology in MS. Several limitations of PET include limited availability of scanners, limited spatial resolution, and significant costs related to radiotracer production. Perhaps the best data exist for PET markers of microglia. Several radiotracers bind to translocator protein, which is a marker of activated microglia: 11C-PK11195 [118], 11C vinopectine [119], 11C-PBR28 [120]. These markers have been shown both in gray [118] and white matter [121], have shown correlation with disability, and in some cases correlate with the presence of microglia in postmortem studies [122]. PET studies have measured myelin with ligands such as C-11-labeled N-methyl-4,4′-diaminostilbene, which is proposed as a probe sensitive to myelin in animal testing [123].11C-PIB has been tested in 2 patients with MS showing promise as a potential myelin marker [124]. More nonspecific markers such as fluorodeoxyglucose has been used as a marker of inflammation [125] and cortical metabolism/cognition [126]. Although PET markers hold great promise for the future the number of patients studied using this technology remain limited and significant barriers, such as cost, access to PET machines, and low resolution, will have to be addressed before this imaging modality can receive widespread use as a biomarker in MS.

Optical Coherence Tomography as a Biomarker in MS

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive method that is useful for imaging the retina. OCT technology similar to B-mode ultrasound relies on low coherent infrared light to obtain high spatial resolution images of the retina [127]. OCT has significant advantages as it is noninvasive, relatively inexpensive, easy to perform in the office setting, fast, and produces quantitative measures reliably. OCT is able to characterize pathology in the retina as it relates to injury of the optic nerve, and also may serve as a window into underlying changes in the entire central nervous system. As such, OCT holds significant promise as a biomarker in MS. The most recent generation of OCT machines (spectral domain OCT) provide better resolution with decreased scan times than older time-domain machines [128]. OCT enables measurement of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), thought to be a marker of axon loss and the neuronal ganglion cell layer.

After optic neuritis a clear drop in RNFL thickness can be observed with OCT [129, 130] Loss of RNFL appears to affect preferentially the temporal region of the retina and tends to occur in the first several months after acute optic neuritis [131]. It has been demonstrated that RNFL is thinner in patients with MS than in healthy controls, even in patients with MS who have not had episodes of optic neuritis [132]. This last finding suggests OCT may be measuring a more diffuse pathological process which better corresponds to overall central nervous system damage, although, alternatively, it may be simply measuring subclinical optic neuritis. Longitudinal evaluation using OCT demonstrates progressive loss of RNFL, and this is seen in eyes both with and without a history of optic neuritis [131, 133].

Several studies have examined the relation between RNFL thickness and more global measures of injury in MS, including clinical manifestations and brain MRI changes. Changes in letter acuity and low-contrast letter acuity are associated with RNFL thickness in longitudinal studies [134]. RNFL has been correlated with brain atrophy [135], T2 lesion volume [136], severity of injury in the spinal cord [137], and DTI measures of brain white matter [138]. RNFL thickness seems to be a useful method for differentiating patients with MS from those with neuromyelitis optica [139, 140].

Measurement of ganglion cell layer thickness has emerged as a valuable OCT marker, possibly representing a pathological process other than pure axon loss. Ganglion cell thickness in some studies was found to have better correlations with visual function [141, 142], and mirrors findings comparing white matter and gray matter atrophy. Finally, macular volume can be used as a measure of neuronal loss in MS and has been shown to mirror RNFL loss as well [143]. The use of OCT to measure macular volume in the clinic serves to screen for macular edema in patients starting fingolimod, or for surveillance once the medication is started [144].

Imaging as an Early Biomarker for Progressive MS

In RRMS contrast-enhancing lesions have served as a useful outcome in phase II studies to screen for the relative potency of anti-inflammatory MS therapies. In progressive MS a similar outcome has not been identified, representing a significant challenge to the development of therapies. MRI methods described above, especially brain atrophy, are reasonable candidates but may reflect downstream pathology and may require both long studies and large sample sizes. Advanced metrics such as DTI, MTR, and OCT are promising as phase II outcomes, but still need further validation. The Progressive MS Alliance is currently focusing on identification and validation of potential outcome metrics for faster clinical trials [145].

Conclusion

Imaging markers have demonstrated significant utility as biomarkers in MS. Development of new brain lesions is perhaps the most useful biomarker available in the early stages of MS and is used routinely in clinical practice to monitor therapeutic response. New lesions are not a useful biomarker in progressive MS, although several advanced imaging candidates and ultra-high filed MRI of the brain and spinal cord hold significant promise for filling that unmet need. Large validation studies of these methods will be needed so that these advanced imaging biomarkers can be applied reliably in the clinical setting and to test new therapeutics.

References

Torkildsen O, Myhr KM, Bo L. Disease-modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis—a review of approved medications. Eur J Neurol 2016;23(Suppl. 1):18-27.

Sormani MP, Bruzzi P. MRI lesions as a surrogate for relapses in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:669-676.

Willoughby EW, Grochowski E, Li DK, Oger J, Kastrukoff LF, Paty DW. Serial magnetic resonance scanning in multiple sclerosis: a second prospective study in relapsing patients. Ann Neurol 1989;25:43-49.

Isaac C, Li DK, Genton M, et al. Multiple sclerosis: a serial study using MRI in relapsing patients. Neurology 1988;38:1511-1515.

Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Frequin ST, et al. Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: sequential enhanced MR imaging vs clinical findings in determining disease activity. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992;159:1041-1047.

Filippi M, Rossi P, Campi A, Colombo B, Pereira C, Comi G. Serial contrast-enhanced MR in patients with multiple sclerosis and varying levels of disability. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997;18:1549-1556.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292-302.

van Waesberghe JH, Kamphorst W, De Groot CJ, et al. Axonal loss in multiple sclerosis lesions: magnetic resonance imaging insights into substrates of disability. Ann Neurol 1999;46:747-754.

Tam RC, Traboulsee A, Riddehough A, Sheikhzadeh F, Li DK. The impact of intensity variations in T1-hypointense lesions on clinical correlations in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2011;17:949-957.

Vellinga MM, Geurts JJ, Rostrup E, et al. Clinical correlations of brain lesion distribution in multiple sclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009;29:768-773.

Minneboo A, Barkhof F, Polman CH, Uitdehaag BM, Knol DL, Castelijns JA. Infratentorial lesions predict long-term disability in patients with initial findings suggestive of multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2004;61:217-221.

Filippi M, Rocca MA, Ciccarelli O, et al. MRI criteria for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: MAGNIMS consensus guidelines. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:292-303.

Sormani MP, Bonzano L, Roccatagliata L, Cutter GR, Mancardi GL, Bruzzi P. Magnetic resonance imaging as a potential surrogate for relapses in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analytic approach. Ann Neurol 2009;65:268-275.

Bermel RA, You X, Foulds P, et al. Predictors of long-term outcome in multiple sclerosis patients treated with interferon beta. Ann Neurol 2013;73:95-103.

Sormani MP, Rio J, Tintore M, et al. Scoring treatment response in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2013;19:605-612.

Bevan CJ, Cree BA. Disease activity free status: a new end point for a new era in multiple sclerosis clinical research? JAMA Neurol 2014;71:269-270.

Freedman MS. Are we in need of NEDA? Mult Scler 2016;22:5-6.

Stangel M, Penner IK, Kallmann BA, Lukas C, Kieseier BC. Towards the implementation of 'no evidence of disease activity' in multiple sclerosis treatment: the multiple sclerosis decision model. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2015;8:3-13.

Ziemssen T, Derfuss T, de Stefano N, et al. Optimizing treatment success in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2016;263:1053-1065.

Tallantyre EC, Dixon JE, Donaldson I, et al. Ultra-high-field imaging distinguishes MS lesions from asymptomatic white matter lesions. Neurology 2011;76:534-539.

Mistry N, Dixon J, Tallantyre E, et al. Central veins in brain lesions visualized with high-field magnetic resonance imaging: a pathologically specific diagnostic biomarker for inflammatory demyelination in the brain. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:623-628.

Fisher E, Rudick RA, Simon JH, et al. Eight-year follow-up study of brain atrophy in patients with MS. Neurology 2002;59:1412-1420.

Maghzi AH, Revirajan N, Julian LJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging correlates of clinical outcomes in early multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2014;3:720-727.

Sastre-Garriga J, Arevalo MJ, Renom M, et al. Brain volumetry counterparts of cognitive impairment in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2009;282:120-124.

Lazeron RH, Boringa JB, Schouten M, et al. Brain atrophy and lesion load as explaining parameters for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2005;11:524-531.

Khoury S, Bakshi R. Cerebral pseudoatrophy or real atrophy after therapy in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2010;68:778-779.

van den Elskamp IJ, Boden B, Dattola V, et al. Cerebral atrophy as outcome measure in short-term phase 2 clinical trials in multiple sclerosis. Neuroradiology 2010;52:875-881.

Altmann DR, Jasperse B, Barkhof F, et al. Sample sizes for brain atrophy outcomes in trials for secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2009;72:595-601.

Kappos L, De Stefano N, Freedman MS, et al. Inclusion of brain volume loss in a revised measure of 'no evidence of disease activity' (NEDA-4) in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2016;22:1297-1305.

Fisniku LK, Chard DT, Jackson JS, et al. Gray matter atrophy is related to long-term disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2008;64:247-254.

Rudick RA, Lee JC, Nakamura K, Fisher E. Gray matter atrophy correlates with MS disability progression measured with MSFC but not EDSS. J Neurol Sci 2009;282:106-111.

Dalton CM, Chard DT, Davies GR, et al. Early development of multiple sclerosis is associated with progressive grey matter atrophy in patients presenting with clinically isolated syndromes. Brain 2004;127:1101-1107.

Labiano-Fontcuberta A, Mato-Abad V, Alvarez-Linera J, et al. Gray matter involvement in radiologically isolated syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3208.

Nourbakhsh B, Nunan-Saah J, Maghzi AH, et al. Longitudinal associations between MRI and cognitive changes in very early MS. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2016;5:47-52.

Modica CM, Bergsland N, Dwyer MG, et al. Cognitive reserve moderates the impact of subcortical gray matter atrophy on neuropsychological status in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2016;22:36-42.

Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 2012;62:774-781.

Narayana PA, Govindarajan KA, Goel P, et al. Regional cortical thickness in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis: a multi-center study. Neuroimage Clin 2012;2:120-131.

Govindarajan KA, Datta S, Hasan KM, et al. Effect of in-painting on cortical thickness measurements in multiple sclerosis: a large cohort study. Hum Brain Mapp 2015;36:3749-3760.

Nakamura K, Fox R, Fisher E. CLADA: cortical longitudinal atrophy detection algorithm. Neuroimage 2011;54:278-289.

Azevedo CJ, Overton E, Khadka S, et al. Early CNS neurodegeneration in radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015;2:e102.

Mesaros S, Rocca MA, Absinta M, et al. Evidence of thalamic gray matter loss in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2008;70:1107-1112.

Bergsland N, Zivadinov R, Dwyer MG, Weinstock-Guttman B, Benedict RH. Localized atrophy of the thalamus and slowed cognitive processing speed in MS patients. Mult Scler 2016;22:1327-1336..

Houtchens MK, Benedict RH, Killiany R, et al. Thalamic atrophy and cognition in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2007;69:1213-1223.

Koini M, Filippi M, Rocca MA, et al. Correlates of executive functions in multiple sclerosis based on structural and functional MR imaging: insights from a multicenter study. Radiology 2016:151809.

Motl RW, Zivadinov R, Bergsland N, Benedict RH. Thalamus volume and ambulation in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2016;6:23-29.

Wilting J, Rolfsnes HO, Zimmermann H, et al. Structural correlates for fatigue in early relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur Radiol 2016;26:515-523.

Sicotte NL, Kern KC, Giesser BS, et al. Regional hippocampal atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2008;131:1134-1141.

Bermel RA, Innus MD, Tjoa CW, Bakshi R. Selective caudate atrophy in multiple sclerosis: a 3D MRI parcellation study. Neuroreport 2003;14:335-339.

Bermel RA, Bakshi R, Tjoa C, Puli SR, Jacobs L. Bicaudate ratio as a magnetic resonance imaging marker of brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2002;59:275-280.

Bo L, Geurts JJ, Mork SJ, van der Valk P. Grey matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 2006;183:48-50.

Peterson JW, Bo L, Mork S, Chang A, Trapp BD. Transected neurites, apoptotic neurons, and reduced inflammation in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol 2001;50:389-400.

Bo L, Vedeler CA, Nyland HI, Trapp BD, Mork SJ. Subpial demyelination in the cerebral cortex of multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2003;62:723-732.

Kidd D, Barkhof F, McConnell R, Algra PR, Allen IV, Revesz T. Cortical lesions in multiple sclerosis. Brain 1999;122:17-26.

Calabrese M, Filippi M, Gallo P. Cortical lesions in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2010;6:438-444.

Geurts JJ, Bo L, Pouwels PJ, Castelijns JA, Polman CH, Barkhof F. Cortical lesions in multiple sclerosis: combined postmortem MR imaging and histopathology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:572-577.

Geurts JJ, Pouwels PJ, Uitdehaag BM, Polman CH, Barkhof F, Castelijns JA. Intracortical lesions in multiple sclerosis: improved detection with 3D double inversion-recovery MR imaging. Radiology 2005;236:254-260.

Tallantyre EC, Morgan PS, Dixon JE, et al. 3 Tesla and 7 Tesla MRI of multiple sclerosis cortical lesions. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010;32:971-977.

Calabrese M, Agosta F, Rinaldi F, et al. Cortical lesions and atrophy associated with cognitive impairment in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1144-1150.

Haider L, Simeonidou C, Steinberger G, et al. Multiple sclerosis deep grey matter: the relation between demyelination, neurodegeneration, inflammation and iron. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:1386-1395.

Catalaa I, Fulton JC, Zhang X, et al. MR imaging quantitation of gray matter involvement in multiple sclerosis and its correlation with disability measures and neurocognitive testing. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:1613-1618.

Harrison DM, Roy S, Oh J, et al. Association of cortical lesion burden on 7-T magnetic resonance imaging with cognition and disability in multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:1004-1012.

Fox RJ. Picturing multiple sclerosis: conventional and diffusion tensor imaging. Semin Neurol 2008;28:453-466.

Klawiter EC, Schmidt RE, Trinkaus K, et al. Radial diffusivity predicts demyelination in ex vivo multiple sclerosis spinal cords. Neuroimage 2011;55:1454-1460.

Song SK, Yoshino J, Le TQ, et al. Demyelination increases radial diffusivity in corpus callosum of mouse brain. Neuroimage 2005;26:132-140.

Budde MD, Xie M, Cross AH, Song SK. Axial diffusivity is the primary correlate of axonal injury in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis spinal cord: a quantitative pixelwise analysis. J Neurosci 2009;29:2805-2813.

Fox RJ, Cronin T, Lin J, et al. Measuring myelin repair and axonal loss with diffusion tensor imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:85-91.

Harrison DM, Caffo BS, Shiee N, et al. Longitudinal changes in diffusion tensor-based quantitative MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2011;76:179-186.

Naismith RT, Xu J, Tutlam NT, et al. Increased diffusivity in acute multiple sclerosis lesions predicts risk of black hole. Neurology 2010;74:1694-1701.

Ontaneda D, Sakaie K, Lin J, Lowe MJ, Phillips MD, Fox RJ. Diffusion tensor imaging before, during and after progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:e36-e38.

Fox RJ, Sakaie K, Lee JC, et al. A validation study of multicenter diffusion tensor imaging: reliability of fractional anisotropy and diffusivity values. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:695-700.

Caverzasi E, Papinutto N, Castellano A, et al. Neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging color maps to characterize brain diffusion in neurologic disorders. J Neuroimaging 2016;26:494-498.

Filippi M, Rocca MA. Present and future of fMRI in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother 2013;13(12 Suppl.):27-31.

Penner IK, Rausch M, Kappos L, Opwis K, Radu EW. Analysis of impairment related functional architecture in MS patients during performance of different attention tasks. J Neurol 2003;250:461-472.

Mainero C, Caramia F, Pozzilli C, et al. fMRI evidence of brain reorganization during attention and memory tasks in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage 2004;21:858-867.

Louapre C, Perlbarg V, Garcia-Lorenzo D, et al. Brain networks disconnection in early multiple sclerosis cognitive deficits: an anatomofunctional study. Hum Brain Mapp 2014;35:4706-4717.

Lowe MJ, Koenig KA, Beall EB, et al. Anatomic connectivity assessed using pathway radial diffusivity is related to functional connectivity in monosynaptic pathways. Brain Connect 2014;4:558-565.

Henkelman RM, Stanisz GJ, Graham SJ. Magnetization transfer in MRI: a review. NMR Biomed 2001;14:57-64.

Schmierer K, Scaravilli F, Altmann DR, Barker GJ, Miller DH. Magnetization transfer ratio and myelin in postmortem multiple sclerosis brain. Ann Neurol 2004;56:407-415.

Vavasour IM, Laule C, Li DK, Traboulsee AL, MacKay AL. Is the magnetization transfer ratio a marker for myelin in multiple sclerosis? J Magn Reson Imaging 2011;33:713-718.

Chen JT, Collins DL, Atkins HL, Freedman MS, Arnold DL, Canadian MS/BMT Study Group. Magnetization transfer ratio evolution with demyelination and remyelination in multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol 2008;63:254-262.

Chen JT, Easley K, Schneider C, et al. Clinically feasible MTR is sensitive to cortical demyelination in MS. Neurology 2013;80:246-252.

Fjaer S, Bo L, Lundervold A, et al. Deep gray matter demyelination detected by magnetization transfer ratio in the cuprizone model. PLoS One 2013;8:e84162.

Traboulsee A, Dehmeshki J, Peters KR, et al. Disability in multiple sclerosis is related to normal appearing brain tissue MTR histogram abnormalities. Mult Scler 2003;9:566-573.

Amann M, Papadopoulou A, Andelova M, et al. Magnetization transfer ratio in lesions rather than normal-appearing brain relates to disability in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2015;262:1909-1917.

Kitzler HH, Su J, Zeineh M, et al. Deficient MWF mapping in multiple sclerosis using 3D whole-brain multi-component relaxation MRI. Neuroimage 2012;59:2670-2677.

Kolind S, Seddigh A, Combes A, et al. Brain and cord myelin water imaging: a progressive multiple sclerosis biomarker. Neuroimage Clin 2015;9:574-580.

Dutta R, Trapp BD. Pathogenesis of axonal and neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2007;68(22 Suppl 3):S22-S31.

Petracca M, Vancea RO, Fleysher L, Jonkman LE, Oesingmann N, Inglese M. Brain intra- and extracellular sodium concentration in multiple sclerosis: a 7 T MRI study. Brain 2016;139:795-806.

Ruiz-Pena JL, Pinero P, Sellers G, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of normal appearing white matter in early relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: correlations between disability and spectroscopy. BMC Neurol 2004;4:8.

Khan O, Seraji-Bozorgzad N, Bao F, et al. The relationship between brain MR spectroscopy and disability in multiple sclerosis: 20-year data from the U.S. Glatiramer Acetate Extension Study. J Neuroimaging 2016 May 23 [Epub ahead of print].

Narayana PA. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the monitoring of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging 2005;15(4 Suppl.):46S-57S.

Cawley N, Solanky BS, Muhlert N, et al. Reduced gamma-aminobutyric acid concentration is associated with physical disability in progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain 2015;138:2584-2595.

Srinivasan R, Sailasuta N, Hurd R, Nelson S, Pelletier D. Evidence of elevated glutamate in multiple sclerosis using magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 3 T. Brain 2005;128:1016-1025.

Bonek R, Sokolska E, Kurkiewicz T, Maciejek Z. Demyelinating lesions in cervical spinal cord and disability in multiple sclerosis patients. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2004;38:25-29.

Norman D, Mills CM, Brant-Zawadzki M, Yeates A, Crooks LE, Kaufman L. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spinal cord and canal: potentials and limitations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1983;141:1147-1152.

Kidd D, Thorpe JW, Kendall BE, et al. MRI dynamics of brain and spinal cord in progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;60:15-19.

Lukas C, Sombekke MH, Bellenberg B, et al. Relevance of spinal cord abnormalities to clinical disability in multiple sclerosis: MR imaging findings in a large cohort of patients. Radiology 2013;269:542-552.

Lycklama G, Thompson A, Filippi M, et al. Spinal-cord MRI in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2003;2:555-562.

Sombekke MH, Wattjes MP, Balk LJ, et al. Spinal cord lesions in patients with clinically isolated syndrome: a powerful tool in diagnosis and prognosis. Neurology 2013;80:69-75.

Okuda DT, Mowry EM, Cree BA, et al. Asymptomatic spinal cord lesions predict disease progression in radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurology 2011;76:686-692.

Bieniek M, Altmann DR, Davies GR, et al. Cord atrophy separates early primary progressive and relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:1036-1039.

Furby J, Hayton T, Anderson V, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging measures of brain and spinal cord atrophy correlate with clinical impairment in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2008;14:1068-1075.

Lin X, Tench CR, Turner B, Blumhardt LD, Constantinescu CS. Spinal cord atrophy and disability in multiple sclerosis over four years: application of a reproducible automated technique in monitoring disease progression in a cohort of the interferon beta-1a (Rebif) treatment trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1090-1094.

Kalkers NF, Barkhof F, Bergers E, van Schijndel R, Polman CH. The effect of the neuroprotective agent riluzole on MRI parameters in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Mult Scler 2002;8:532-533.

Rocca MA, Valsasina P, Damjanovic D, et al. Voxel-wise mapping of cervical cord damage in multiple sclerosis patients with different clinical phenotypes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013;84:35-41.

Valsasina P, Rocca MA, Horsfield MA, et al. Regional cervical cord atrophy and disability in multiple sclerosis: a voxel-based analysis. Radiology 2013;266:853-861.

Oh J, Zackowski K, Chen M, et al. Multiparametric MRI correlates of sensorimotor function in the spinal cord in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2013;19:427-435.

Ciccarelli O, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, McLean MA, et al. Spinal cord spectroscopy and diffusion-based tractography to assess acute disability in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2007;130:2220-2231.

Agosta F, Pagani E, Caputo D, Filippi M. Associations between cervical cord gray matter damage and disability in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2007;64:1302-1305.

Kearney H, Yiannakas MC, Samson RS, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Ciccarelli O, Miller DH. Investigation of magnetization transfer ratio-derived pial and subpial abnormalities in the multiple sclerosis spinal cord. Brain 2014;137:2456-2468.

Bellenberg B, Busch M, Trampe N, Gold R, Chan A, Lukas C. 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy in diffuse and focal cervical cord lesions in multiple sclerosis. Eur Radiol 2013;23:3379-3392.

Sigmund EE, Suero GA, Hu C, et al. High-resolution human cervical spinal cord imaging at 7 T. NMR Biomed 2012;25:891-899.

Dula AN, Pawate S, Dortch RD, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spinal cord in multiple sclerosis at 7T. Mult Scler 2016;22:320-328.

Gilmore CP, Bo L, Owens T, Lowe J, Esiri MM, Evangelou N. Spinal cord gray matter demyelination in multiple sclerosis-a novel pattern of residual plaque morphology. Brain Pathol 2006;16:202-208.

Laule C, Yung A, Pavolva V, et al. High-resolution myelin water imaging in post-mortem multiple sclerosis spinal cord: a case report. Mult Scler 2016 Jan 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Faria Dde P, Copray S, Buchpiguel C, Dierckx R, de Vries E. PET imaging in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmun Pharmacol 2014;9:468-482.

Delso G, Ter Voert E, Veit-Haibach P. How does PET/MR work? Basic physics for physicians. Abdom Imaging 2015;40:1352-1357.

Politis M, Giannetti P, Su P, et al. Increased PK11195 PET binding in the cortex of patients with MS correlates with disability. Neurology 2012;79:523-530.

Vas A, Shchukin Y, Karrenbauer VD, et al. Functional neuroimaging in multiple sclerosis with radiolabelled glia markers: preliminary comparative PET studies with [11C]vinpocetine and [11C]PK11195 in patients. J Neurol Sci 2008;264:9-17.

Oh U, Fujita M, Ikonomidou VN, et al. Translocator protein PET imaging for glial activation in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2011;6:354-361.

Giannetti P, Politis M, Su P, et al. Increased PK11195-PET binding in normal-appearing white matter in clinically isolated syndrome. Brain 2015;138:110-119.

Banati RB, Newcombe J, Gunn RN, et al. The peripheral benzodiazepine binding site in the brain in multiple sclerosis: quantitative in vivo imaging of microglia as a measure of disease activity. Brain 2000;123:2321-2337.

Wu C, Wang C, Popescu DC, et al. A novel PET marker for in vivo quantification of myelination. Bioorg Med Chem 2010;18:8592-8599.

Stankoff B, Freeman L, Aigrot MS, et al. Imaging central nervous system myelin by positron emission tomography in multiple sclerosis using [methyl-(1)(1)C]-2-(4'-methylaminophenyl)- 6-hydroxybenzothiazole. Ann Neurol 2011;69:673-680.

Buck D, Forschler A, Lapa C, et al. 18F-FDG PET detects inflammatory infiltrates in spinal cord experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis lesions. J Nucl Med 2012;53:1269-1276.

Paulesu E, Perani D, Fazio F, et al. Functional basis of memory impairment in multiple sclerosis: a[18F]FDG PET study. Neuroimage 1996;4:87-96.

Drexler W, Fujimoto JG. State-of-the-art retinal optical coherence tomography. Prog Retin Eye Res 2008;27:45-88.

Chen TC, Cense B, Pierce MC, et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography: ultra-high speed, ultra-high resolution ophthalmic imaging. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:1715-1720.

Costello F, Coupland S, Hodge W, et al. Quantifying axonal loss after optic neuritis with optical coherence tomography. Ann Neurol 2006;59:963-969.

Parisi V, Manni G, Spadaro M, et al. Correlation between morphological and functional retinal impairment in multiple sclerosis patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999;40:2520-2527.

Costello F, Hodge W, Pan YI, Eggenberger E, Coupland S, Kardon RH. Tracking retinal nerve fiber layer loss after optic neuritis: a prospective study using optical coherence tomography. Mult Scler 2008;14:893-905.

Fisher JB, Jacobs DA, Markowitz CE, et al. Relation of visual function to retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmology 2006;113:324-332.

Herrero R, Garcia-Martin E, Almarcegui C, et al. Progressive degeneration of the retinal nerve fiber layer in patients with multiple sclerosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:8344-8349.

Talman LS, Bisker ER, Sackel DJ, et al. Longitudinal study of vision and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2010;67:749-760.

Siger M, Dziegielewski K, Jasek L, et al. Optical coherence tomography in multiple sclerosis: thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer as a potential measure of axonal loss and brain atrophy. J Neurol 2008;255:1555-1560.

Grazioli E, Zivadinov R, Weinstock-Guttman B, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness is associated with brain MRI outcomes in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2008;268:12-17.

Oh J, Sotirchos ES, Saidha S, et al. Relationships between quantitative spinal cord MRI and retinal layers in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2015;84:720-728.

Scheel M, Finke C, Oberwahrenbrock T, et al. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness correlates with brain white matter damage in multiple sclerosis: a combined optical coherence tomography and diffusion tensor imaging study. Mult Scler 2014;20:1904-1907.

Park KA, Kim J, Oh SY. Analysis of spectral domain optical coherence tomography measurements in optic neuritis: differences in neuromyelitis optica, multiple sclerosis, isolated optic neuritis and normal healthy controls. Acta Ophthalmol 2014;92:e57-e65.

Bennett JL, de Seze J, Lana-Peixoto M, et al. Neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis: Seeing differences through optical coherence tomography. Mult Scler 2015;21:678-688.

Walter SD, Ishikawa H, Galetta KM, et al. Ganglion cell loss in relation to visual disability in multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmology 2012;119:1250-1257.

Saidha S, Syc SB, Durbin MK, et al. Visual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis correlates better with optical coherence tomography derived estimates of macular ganglion cell layer thickness than peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Mult Scler 2011;17:1449-1463.

Burkholder BM, Osborne B, Loguidice MJ, et al. Macular volume determined by optical coherence tomography as a measure of neuronal loss in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1366-1372.

Zarbin MA, Jampol LM, Jager RD, et al. Ophthalmic evaluations in clinical studies of fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmology 2013;120:1432-1439.

International Progressive MS Alliance. Priority areas. Available at: http://www.progressivemsalliance.org/about-us/priority-areas/. Accessed June 26, 2016.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 1225 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ontaneda, D., Fox, R.J. Imaging as an Outcome Measure in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 14, 24–34 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-016-0479-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-016-0479-6